Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

A Marv in the palm of your hand

I once knew a mechanic named Marv. (Could there be a better name for a mechanic? Picture him: Brylcreemed black hair combed back in a bit of a pompadour; grey trousers and shirt with “Marv” on a shoulder patch, oil-stained loafers, and perfect white socks. That’s Marv.)

Marv had a shop in which he built hot rods for fun while doing ordinary mechanical work to pay bills. He had the contract to maintain J.C. Penney’s furniture-delivery trucks when I was driving them after high school.

The thing about Marv was, vehicles talked to him. I don’t think I ever saw him have to do more than listen to a truck or car for a few seconds before perfectly diagnosing its issue. “Throwout bearing,” he said into my window when I pulled up in a truck that was making a strange noise during shifts—before I even parked or mentioned the specific complaint. “Front U-joint,” “Water pump,” “Burned exhaust valve”—those are Marv diagnoses off the top of my memory. I once brought in a truck that had started running rough, and he said, “The timing’s slipped.” Did he go fetch his timing light? Nope—he pulled out a half-inch wrench, loosened the nut on the V8’s distributor, turned it with his head cocked to the side, revved it a couple of times, tightened the nut, and said, “There you go.” That time, one of my co-drivers (Vern—could there be a better name for a furniture-delivery man?) was with me. He knew Marv well, but not well enough.

“What’s the timing supposed to be?” Vern asked.

“About seven degrees before top dead center.”

“And how close do you think you got to that?”

Marv said nothing, just fetched his timing light and, well, I bet you can guess the rest by this point. Some time after that I was summarily fired for rapelling off the J.C. Penney warehouse roof (just for fun—a story for another time), and I lost track of Marv and his preternatural skill.

Today? Today any rookie with 20 bucks, an Amazon account, and a smart phone can enjoy a near-Marv-like mind-meld with an OBDII-equipped vehicle two days after clicking “Add to cart.” I know, because I finally ordered a KingMansion ELM 327 wi-fi-enabled OBDII reader that sends all sorts of interesting and useful information to my iPhone, including stuff even Marv couldn’t have determined (although I doubt it could identify a faulty throwout bearing). The only catch is, you’ll also need a compatible app for the phone—cheap if you buy something like the $10 OBD Fusion in the iTunes app store, more expensive if, like me, you don’t pay attention and wind up with one that also synchs with the phone’s accelerometer to record 0-to-60, G-force, and lap times. If I ever decide to try for a new Tacoma/Four-Wheel-Camper lap record at Riverside, I’m all set.

In case you don’t pay attention to such things, OBDII (for On Board Diagnostics) is a standardized system and port (in the U.S.), mandatory on all passenger vehicles since 1996. It allows the vehicle’s CPU (central processing unit) to communicate information about the engine’s emissions (the original intent), instantaneous fuel usage, actual engine temperature, engine load, air intake temperature, and much more, depending on what the vehicle’s manufacturer chooses to make available.

Most useful for owners, however, is the ability to read trouble codes when the dashboard energizes that annoying and oh-so-vague “Check engine” light, which could indicate anything from imminent disaster to something utterly harmless such as a failed reverse lockout switch (this happened on our old Tacoma).

I followed the instructions on the absurdly inconsequential-looking ELM, and within minutes the Tacoma was assuring me all was well fault-code-wise. Other functions such as instantaneous fuel mileage (full throttle in first gear with a camper = 7.142 mpg) also popped up and worked perfectly.

If you do hook up an OBD scanner in response to the check-engine light, don’t expect a little pompadoured Marv to pop up on the screen and tell you what’s wrong and how to fix it. All you’re going to see is an alphanumeric code (or perhaps several). You need a guide to tell you which of a mind-boggling array of faults you are experiencing. It might be, say, code P0812, indicating a reverse switch malfunction, which you can ignore if you’re in the middle of nowhere, or, say, P0304, indicating a misfire in cylinder four, which you would not want to ignore. Codes that begin with a P0, P2, or P3 are universal codes; those that begin with P1 are manufacturer-specific. Many websites have been created solely to list and explain OBDII codes. (Toyota has a professional site here that caters mostly to mechanics, but you can apparently buy a temporary subscription to retrieve current technical bulletins and OBD codes. I write “apparently” because it’s only compatible with PCs—and only using Internet Explorer, for God’s sake. C’mon, Toyota.)

By far the most likely scenario is that even after you look up the code you’ll be presented with some utterly incomprehensible diagnosis, such as P0608, “Control Module VSS output A malfunction.” The reason for this is that, when the people in charge were programming what the standardized OBDII sensor would monitor and flag, they decided they wanted it to be the equivalent of the most hypochondriac human being on the planet—just to be safe, and to give car dealers plenty of work. So—I have no proof of this yet, but I’ll get to the bottom of it—I’m virtually certain they kidnapped my mother, hooked up electrodes to her in a secret research facility in Detroit, and remarked admiringly, “Wow—we need at least 360 potential fault codes.”

Whatever the case, you’ll have to decide whether one of these obscure codes is reason to abandon a trip and head to a mechanic. My own reaction, if the truck were running well with no outward signs of trouble, would probably be to mutter, “Yes, mom, whatever you say,” and keep right on driving.

How to sell aftermarket brakes

The stock brakes on our 2012 Tacoma are . . . adequate . . . with the Four Wheel Camper mounted. On long, twisty downhill roads—I'm talking six, eight, ten miles here—I can feel the pedal begin to get mushy and brake effort increase. When Roseann was hauling a full cargo trailer north to Flagstaff this spring, on the descent into the Salt River Canyon she kept the six-speed (manual) transmission in third to maximize engine braking, but still described brake feel as "Decidedly mushy."

So I've been shopping for potential upgrades to the front discs (Tacomas, to Toyota's discredit, still come with rear drum brakes, which incorporate technology that reached its peak sometime in the 1950s and which are impossible to modify effectively).

One obvious possibility is Toyota's own TRD (Toyota Racing Development), but they didn't list a kit for the 4X4 Tacoma. Next up was Brembo, legendary supplier to such marques as Porsche and Ferrari. I Googled "Tacoma Brembo brakes," and indeed found what appeared to be a source for a Brembo kit. Rather eagerly I looked to the description for technical details, to determine just how the Brembos would improve on the stock brakes.

And here is the entire pitch for this ($1,600) kit from this company:

Brembo GT Slotted Brake Kit Features

- You won't find a cooler looking or operating brake kit than the Brembo GT Slotted Brake Kit.

- Nothing accents a vehicles wheels better than a trick looking Slotted brembo rotor and painted brembo caliper.

- Do yourself and your vehicle a favor and bolt-on a Brembo GT Slotted Brake Kit and give your friends something new to envy.

Words fail . . .

(And never mind the spelling and grammar . . .)

They don't make 'em like they used to

It’s futile to compare modern vehicles with those manufactured 40 years ago. A good ole boy can look at, say, a current Ford F150, with its plastic front bumper, compare it to the steel counterpart on his 1970 predecessor, and drawl, “They don’t make ‘em like they used to.” And he’s correct—but not in the way he thinks. That modern truck will protect its passengers in a wreck that would have left the occupants of the earlier one dead.

Credit a Mercedes Benz engineer named Béla Barényi, who in the 1950s first questioned the prevailing wisdom that a vehicle had to be rigid to be safe. He realized what now seems obvious: that the forces in a collision have to be absorbed somewhere, and if they are not absorbed by the vehicle they will be absorbed by its occupants. This led to the development of front and rear crumple zones, which sacrificed part of the vehicle’s integrity to safeguard the rigid cell containing the driver and passengers. With the further advent of, first, lap and then shoulder belts, and then air bags, injury and fatality rates in collisions plummeted.

(If you’re still not convinced, take a look at this revealing video of a test collision between a 2009 Chevy Malibu and a 1959 Chevy Belair, then tell me which car you’d pick to crash in.)

But. Still . . .

The photo above shows me holding up the entire outer “bumper” assembly of our 2012 Toyota Tacoma—including fog lights—with one finger.

Trust me that I have zero doubt as to whether I’d rather be in the Tacoma or my solid-steel 1973 FJ40 in any kind of collision. I remember a tiny misapplication of throttle in the latter that once sent me into a concrete parking bollard at perhaps two miles per hour. I felt the result right down into my spine. The 40 was of course unscratched.

Nevertheless, it seems to me the thing I’m holding has lost the right to even be called a “bumper.” I’m convinced a two-mile-per-hour tap on a parking bollard would necessitate replacing the entire assembly. Imagine the result if you innocently stuck the tongue of a Hi-Lift jack into that front opening and started cranking. This “bumper” is really nothing more than a bumper-like facade.

I realize that wishful thinking along these lines will have as much effect as hoping Toyota will start importing Hiluxes equipped with three-liter turbodiesels, but wouldn’t it be nice if manufacturers offered a front bumper in their “off-road” packages that was stout enough to withstand jacking (and perhaps even bumping), while still conforming to crash standards?

Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide: fourth edition?

I remember waiting in line to pay for my first copy of Tom Sheppard’s Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide, at the decidedly upscale Land Rover dealership in Scottsdale, Arizona. It was 1998, the first, hardbound edition of the book had recently been released, and I’d driven 120 miles with the express purpose of securing a copy. At the counter in front of me, a woman was agonizing (trust me, that’s the right word) over whether to buy the giraffe or rhino-illustrated spare tire cover for her new Discovery II. She vacillated for at least five minutes while I flipped through the thick book, skimming Sheppard’s exhaustive sections on vehicle selection and modification, communications, loading and lashing, navigation, and team selection. I had decided I would definitely not select Disco woman for any team I led, and was about to suggest aloud that, since she had dropped $40,000 on the vehicle, why not buy both the stupid $30 tire covers, when the giraffe won out. (“He’s cuter.”) The gulf between her universe and that in the book I held could have been measured in parsecs.

Back home, I discovered that within the 500-plus pages of the VDEG (say “Veedeg”if you wish to be counted among the cognoscenti) was virtually everything one might need to know to plan, organize, and conduct a vehicle-dependent expedition, whether of 100 or 10,000 miles duration. The stunning level of detail was what one would expect if the author were, say, a former test pilot for the Royal Air Force, or had, for example, led the first lateral crossing of the Sahara Desert in prototype Forward-control Land Rovers, or had driven a further several tens of thousands of miles in that same desert, much of it solo and completely off-tracks. All of which was true of Squadron Leader Tom Sheppard, whose articles I’d been reading for almost two decades. Random example from Section 2.6: two full-page spreads on engine oil characteristics, service categories, and labeling. It seemed excessive—until you realized that oil is quite literally the blood of your vehicle’s engine. There were similar in-depth investigations into wicking fabrics, camping stoves, high-frequency radios, electrical loads, water purification—on and on—plus extensive sections on shipping, 4WD systems, provisioning and cooking, and navigation.

But it wasn’t all technical jargon. The book was liberally sprinkled with personal anecdotes and photos from four decades of exploration. For several weeks my writing schedule suffered as I detoured into Tom Sheppard’s world, and learned as much as I ever did from any university textbook—while having much more fun.

Copies of the original VDEG now sell for hundreds of dollars on eBay (a fact that rankles Tom, who has since become a friend). Through his one-man publishing company, Desert Winds, he has since produced a second and third edition, bound in paperback and printed in black and white to keep them affordable for both Tom and readers. Each was subjected to meticulous updating to reflect advances in vehicles, communications, GPS technology, and countless other details—and even these have been subject to price-gouging. (The original was also published in association with Land Rover; succeeding editions have been independent efforts, arguably allowing Tom more scope when discussing vehicles.)

The third edition of Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide recently sold out. Tom originally thought (swore!) it would be the last, but now he is considering a fourth edition, which would once again be thoroughly updated. If, like me, you own every previous edition, you’ll certainly want this one. If you don’t have a copy of any of them, your overlanding library is tragically incomplete.

Now, here’s the thing: Whether a fourth edition comes to pass is entirely up to you. Tom is tallying the number of people on his email waiting list to determine if he can commit the substantial time and energy to another round of test-pilot-level scrutiny and revisions. You can bet I’m on the list; if you wish to be as well, send an email to him at mail@desertwinds.co.uk. Use a suitably pleading tone, but gently remind him of his duty to the worldwide overlanding community. That works really well on retired RAF squadron leaders.

Desert Winds—i.e. Tom—also publishes several other books, some useful, some merely lovely. You can order them directly from him here.

And an update: It seems Tom's printer found a box of VDEG ed. 3 in a corner. Available while supplies last, probably not long. Then it's on to VDEG ed.4!

Bogert Manufacturing wheel chocks

Chocking your vehicle’s tires is one of the most basic and critical safety procedures you can follow before changing a tire, winching, or working underneath it. Yet how many of us ever use anything but nearby rocks or logs to do so? Not only are you at the mercy of what’s available (Will this work, or do I need that bigger one over there?), but if you happen to be leading a trip or are otherwise in a position of some assumed authority, it lends a rookie taint to your otherwise faultless command presence to be seen looking around for rocks.

I thought about this recently while looking around for rocks.

To make matters worse, I had a good set of chocks with me—the clever folding units made by Land Rover—but they were inconveniently stashed in a compartment under the rear jump seat of the Tacoma, which itself was under several layers of Pelican cases. So I took the lazy route.

Lessons learned: a) Have stuff like this easily accessible, and if it isn’t, b) Follow Graham Jackson’s First Rule of What to Do When There’s Trouble, which is, Slow down and brew a cup of tea, and then Jonathan Hanson’s First Rule of What to Do When There’s Trouble, which is Use the right tools. Sorry Graham. And me.

As much as I like the Land Rover chocks, their lightweight, folding construction pretty much relegated them to tire-changing and working-under duties. Thanks to the fertile mind of Richard Bogert of Bogert Manufacturing, I now have a set of heavy-duty, winching-compatible chocks.

Constructed of 3/16ths-inch steel and heavily powder-coated, the Bogert chocks take up virtually no more room than the folding ones if you stand them on edge in the corner of a cargo box. A set of them comprises not two but, properly, four, so you can anchor two wheels on both sides, or four wheels on one side if you’re on a hill. Additionally, a set of holes and slots in each chock allows you to chain two together on either end of the wheel to prevent shifting if the truck jerks back and forth under a load—nice. Each set of chocks comes with four chains, so you can anchor each pair of chocks on the inside and outside of the wheel if needed. The result is one solidly immobile truck.

The set is now stored in the “Camper Setup” Wolf Pack box that rides just inside the door of the JATAC's Four Wheel Camper. So accessing proper chocks will be as easy as picking up a rock, and my faultless command presence can remain intact.

From now until the end of June, Bogert is offering a 15 percent discount on all their superb recovery tools and accessories. Please use code K7E. Bogert Manufacturing is here.

A stove with character

The SVEA 123 (Courtesy Spiritburner.com)

My first proper backpacking stove (not counting cans of Sterno here) was called a SVEA 123 (pronounced like a word: “Sveyah”). It was a lovely thing of solid brass that ran on white gas and needed no pumping—once primed, a loop in the fuel system atomized the gas picked up from the tank and produced a pressurized flame, accompanied by a distinctive roar that, while comforting, effectively drowned out any sounds of nature one might otherwise be enjoying. Turning off a SVEA was always as pleasurable as lighting it.

The priming procedure was intimidating at first. You were instructed to pour a bit of gas (I eventually hit on using an eye dropper) into a depression at the base of the burner tube, and apply a match—whereupon a jolly little fire would engulf the entire burner assembly. Just as the fire was dying you were to insert the little key into the stove’s control valve and open it. Timed correctly, a fine hot blue flame sprouted under the burner plate. Timed wrong, a foot-high flare of yellow fire indicated insufficient priming. Once going, the SVEA would boil water in a jiffy. Simmering béchamel—not so much. And woe to the user who neglected to remove the key from its fitting in between adjustments—I’m convinced I can still make out the burn scar on my thumb and index finger from repeated failures to do so.

Nothing wrong here; normal starting procedure . . .

If all this sounds a bit dodgy, the SVEA did have a valve in the filler cap that was designed to pop if the internal pressure exceeded safety margins. Just once I had this occur—fortunately when I was making coffee next to a stream in the open, because the result was a foot-long jet of flame that just happened to be pointed away from me. I stood up and kicked the entire stove into the water, instantly dousing both the burner flame as well as the “safety” one. Incredibly, once dried the stove fired up again as if nothing had happened.

That SVEA cost $12.99 if memory serves. I used it for a decade, augmented by a Sigg Tourist cook kit that substituted a much better wind screen for the nearly useless factory number, and included lightweight but thin aluminum pots that did not help the béchamel. Eventually I moved on to more modern and efficient stoves, but I still have that SVEA, and every decade or so I’ll fire it up just to prove it’s ready to go to work again if needed. Every time I do so I'm flooded with visual, olfactory, and auditory memories of trips taken, coffee brewed, and meals enjoyed in beautiful settings accessible only with effort and commitment, and the more splendid for that.

I was reminded of the stove recently while browsing an outdoor store in Boulder, Colorado. Because, you see, you can still buy a SVEA 123, although it’s now made by Optimus. The price has gone up by precisely an order of magnitude:

And some time ago I had another delightful reminder of how an inanimate object can have a personality and become a powerful repository of memories. My friend Ken Swanstrom purchased a SVEA on eBay—normally an anonymous and sterile way to buy something, right? Except for the note that accompanied the stove:

The note is poignant, yet one suspects Bonnie smiled as she wrote it. Had she become too old or busy to ever contemplate using her "trusty" stove again? Whatever her reason to sell, it's clear she is placing some responsibility on its new owner to treat it with the respect it deserves. If I ever sell mine, I'll do the same.

Continental Divide vehicle report

What sort of mischief can 1,600 uninterrupted miles of mixed corrugations, rocks, potholes, mud, and even some pavement wreak on a diverse group of four-wheel-drive vehicles? We found out on the recent Continental Divide trip organized by Rawhyde Adventures and us.

Our lineup on the ten-day journey included two Toyota Tacomas (one mounted with a Four Wheel Camper), two Ford Raptor pickups (one also mounted with a FWC), two Sportsmobiles (nine years apart in age), two Toyota FJ Cruisers (one towing an Adventure Trailer), two four-door Jeep Wranglers, one nicely maintained 1990 Ford Bronco, one newly restored and modified FJ60 Land Cruiser, a four-wheel drive Chevy Van conversion, and, occasionally, a Ford F250 pickup belonging to the Rawhyde staff’s self-taught 21-year-old mechanic/welder/marshmallow toaster (more on that later), Phil. Sadly, a Land Rover Defender 90 powered by a 200TDi diesel failed to make the start, after a blown head gasket and several other issues finally sidelined it despite valiant attempts by its owners to rectify things and meet us partway along the route.

We knew we were pushing the weather envelope on the trip, as it was scheduled right after the Overland Expo WEST, in late May. Additionally, the Rockies had experienced heavy snow fall just prior to our journey, so it was clear in advance some of the high passes would be . . . impassible. However, our group seemed to take this in stride as a more enjoyable challenge than cruising over the same passes might have been later in the year. One attempt, at a high pass above Lake de Nolda and the Alamosa River, involved first pulling a large fallen tree off the trail, then blasting through several drifts until the lead Ford Raptor found itself high-centered, all four wheels rotating uselessly, in a snow bank too deep to shoulder aside. In this case, everyone agreed that trying and failing was more fun than easy success.

Mostly, though, the miles we drove comprised easy to moderate backcountry routes with miles and miles of hammering from corrugations (or washboard if you prefer), and low-speed bouncing over freeze-induced potholes. The effects became apparent early on.

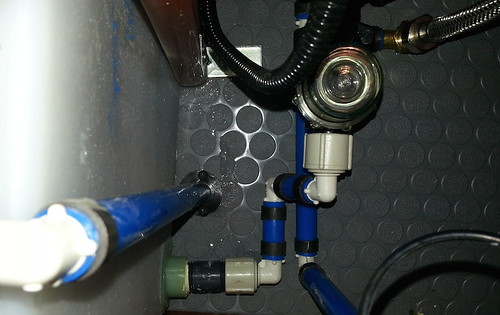

Both Sportsmobile owners glanced back into their living areas during a day’s trek to find their carpets soaked. The rough roads had caused (yet-to-be-determined) leaks in the vehicles’ plumbing systems, resulting in complete loss of water in the main tanks. Despite this, everyone was impressed with the Sportsmobiles’ utility and capability, especially considering their imposing size and 10,000-pound-plus GVW.

The FJ60 had just been the subject of a near-complete rebuild, including the installation of a factory 1HZ six-cylinder diesel engine with a turbo kit, plus a five-speed transmission, along with an extensive array of cargo-containment slides and suspension modifications. In fact, its owner, Adolfo Rapaport, only laid eyes on the vehicle a few days before joining us on the trip.

Among its accessories, the Land Cruiser had a full-length Eezi-Awn “K9” roof rack supporting an Autohome Columbus roof tent. Adolfo was delighted with the effortless setup of the clamshell tent (undo latch, climb in, go to sleep); however, an ominous development hinted at future issues: One of the six brackets supporting the rack failed on the third day of the trip. The aluminum base of the bracket cracked completely through where three holes are drilled in a horizontal line for connection to the steel upper bracket—an obvious potential failure point. Soon another bracket failed, then another. Each time the brackets were shuffled to retain support at the corners, but finally we simply ran out of brackets.

On the second to last day of the trip the mounts gave way altogether, and we pulled the rack and tent off the Land Cruiser and strapped it to the massive construction rack of the Rawhyde F450 support truck that rendezvoused with us each night. Adolfo and his son Josh enjoyed a penthouse apartment from that point on; they just had to avoid an assortment of welding tanks and generators when clambering up and down.

Post-trip investigation by both the chagrined builder of the vehicle and the importer of the rack revealed that the brackets had been completely redesigned sometime after the last container left South Africa, indicating that Eezi-Awn had become aware of the essentially guaranteed failure rate of the original. New brackets (four for each side rather than three) are on the way to Adolfo as I write.

One other issue surfaced on the Land Cruiser: The dual battery mounts in the front of the engine compartment had been engineered so only the rear of each battery was securely clamped, and they quickly worked loose. Folded cardboard provided a temporary but less-than-stylish fix.

The two Jeep Wranglers performed very well, as I expected, although a plastic fitting for the transfer case linkage on one of them failed, and Phil had to secure it temporarily with a zip tie. After a long, slow climb, the automatic transmission oil temperature warning light came on in the other, but it never happened again. And Chrysler still has not solved the problem of mud thrown up from the front tires, which packed the front door handles of both Wranglers with goop. We had this issue with the long-term Wrangler Rubicon we had four years ago. C’mon Jeep—a simple set of abbreviated mud flaps in front would at least keep the arc of the flung mud below the handles.

One of the FJ Cruisers sported a custom combination tire carrier and mount for two four-gallon Roto-Pax fuel containers. The assembly was welded to the stock tire carrier base on the rear door, and early on the four welds began to fail one by one. Fortunately Phil was able to re-weld the mount sufficiently to keep it intact for the remainder of the trip. The location of the Roto-Pax significantly increased the leverage on the mount; I think the fabricator should rethink the design.

Sterling Noren’s clever Chevrolet conversion kept up effortlessly with all the more technologically advanced and prepared four-wheel-drive vehicles, and survived numerous blasts of speed as he raced ahead of the main group to film. But late in the trip, and late each day, the vehicle began dying at random and refusing to move more than a few feet unless it was allowed to cool for an hour or so. No codes showed on the OBD reader, and standard diagnostic investigation was futile, so Sterling simply let the van have a nap when needed.

Both Raptors performed flawlessly, as did both Tacomas. Ross Blair's Tacoma benefitted from conscientious daily checks.

And that 1990 Bronco? It survived the trip in style as well.

On a related note, both Four Wheel Campers performed as they always do, providing a home away from home with a two-minute setup time, and scarcely affecting the backcountry abilities of the vehicles to which they're attached. With that said, the turnbuckle attachment system continues to require frequent checking; I'm determined to come up with a way to solidly anchor them. And, for the second time on ours, a silly strip of rubber trim around the front overhang came loose on a windy stretch of interstate, making a noise all out of proportion to its importance. Quibbles on a superb product, but needing attention.

Other tidbits: Phil, who was towing an enclosed cargo trailer along a very muddy track in our wake on one of the easy sections, looked in his mirrors to note both fenders so loaded with sludge that they were ripping free of the trailer. He unbolted both and tossed them in the bed.

At one point I took over driving a two-wheel-drive support van shod with street tires along a level but treacherously slick muddy section, amusing the following drivers with the yaw angles I achieved while trying to keep the thing on the road. Luck was with me and I avoided ditching it. Total number of vehicle recoveries was remarkably low at three.

Oh, and, regarding Phil and the marshmallows? He proved remarkably apt at toasting them for s'mores with his oxy-acetylene torch.

Update

on 2014-06-12 00:52 by Jonathan Hanson

An update: Michael Collier, the owner of one of the Sportsmobiles that suffered a water leak, reports that the source in his was a connection between the water pump and the lower water tank. These connections have large knurled fittings that are designed to be hand-tightened. Once snugged, Michael says, the system has remained secure. The long-term solution seems to be regular checks while attending to basic daily maintenance.

Old and new OME

My FJ40 Land Cruiser has been riding on an Old Man Emu suspension for about eight years now. It’s OME’s standard kit for the FJ40, comprising a useful but easy-on-driveshaft-angle two-inch lift (which gave me enough room to install 255/85-16 BFG MTs), and low-pressure nitrogen-gas-charged shock absorbers. It’s been flawlessly reliable, and does wonders for the short 90-inch wheelbase of the 40; in fact it rides better over the rough seven-mile dirt and rock approach to our desert cottage than our 2012 Tacoma (128-inch wheelbase) did on its stock springs and shocks, which were far too stiff.

My FJ40 Land Cruiser has been riding on an Old Man Emu suspension for about eight years now. It’s OME’s standard kit for the FJ40, comprising a useful but easy-on-driveshaft-angle two-inch lift (which gave me enough room to install 255/85-16 BFG MTs), and low-pressure nitrogen-gas-charged shock absorbers. It’s been flawlessly reliable, and does wonders for the short 90-inch wheelbase of the 40; in fact it rides better over the rough seven-mile dirt and rock approach to our desert cottage than our 2012 Tacoma (128-inch wheelbase) did on its stock springs and shocks, which were far too stiff.

The suspension is still perfectly functional—there is no obvious sagging and the shocks aren’t leaking—but it’s been looking tired. The shocks are faded and sand-blasted, and in photos I was amazed to see how rusty the springs looked; something I’d apparently become used to in person.

The 40 spends its time at the Overland Expo front and center—it’s either ensconced outside the Overland Oasis tent or used as a winch platform for the Camel Trophy team—and apparently ARB USA, the importers of OME suspension, felt that their springs and shocks shouldn’t be the rattiest looking component of the vehicle, because they supplied me with a replacement kit.

I spent the last couple of days removing the old suspension and installing the shiny new stuff, and it’s clear the FJ40 is feeling chuffed. It always runs a little better after it gets a spa treatment.

But here’s the amazing thing: When I pulled off the old front springs and set one of them next to one of the new springs, the height was . . . close? No—it was identical. Same with the rears. As far as my eye can tell those rusty old springs hadn’t lost a millimeter of height.

Not impressed? Consider this: I bought that original OME kit used. It had been on an FJ40 that was part of a fleet running guided 4WD tours in northern Arizona, and had several years of daily commercial use on it before I gave it a new lease on life, courtesy a local Land Cruiser scrounger who bought the entire fleet, if I recall correctly.

There’s one caveat: Those first OME springs were manufactured in Australia. The replacement set is from their “Dakar” line, which is manufactured in Malaysia (I guess calling it the “Malay” line just wouldn’t have the same cachet). The Dakar springs are made to OME’s specifications, have all the same construction features, and carry the same guarantee as their Australian predecessors, but they simply have not been around long enough to determine if they’ll prove as durable.

Expect an update in 2024.

Cascade effect: I guess I need to paint my axles now . . .

Cascade effect: I guess I need to paint my axles now . . .

Partial non sequitur: Among the myriad animals hanging around our place in the desert (see HERE) are small lizards whose common name is lesser earless, due to the logical fact that they have no external ear openings and are smaller than the greater earless lizard. I suspect lesser earless lizards evolved to follow large herbivores to catch the arthropods they kick up, because they are utterly fearless around humans and often get dangerously underfoot.

While I was replacing the suspension, I somehow lost one of the dished washers that compress the shock absorber eyes. I’ve no idea how I did it; it was simply gone when I went to install the new shock. I must have somehow flicked or kicked it into the gravel next to the concrete, but no amount of searching could unearth it. The washer is a dull gray, as is the gravel. It was maddening.

As I searched, the lesser earless that had been hanging around while I worked kept darting so close I was terrified of stepping on him. Finally, as I was making one last desperate effort to find the washer before giving up and ordering a new one, I again caught in my peripheral vision the lizard darting toward me. I looked down, and it had stopped and was looking up at me—with one foot on the washer.

If it had spoken aloud and said, “Here’s your washer; can I have a bug now?” I wouldn’t have been the slightest bit surprised.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.