In Praise of Pencils

Yesterday, March 30, was National Pencil Day, and coincidentally I've been researching pencils for a new book due out this summer. I’ve learned so much, and now I’m a huge fan of pencils.

Here are some of the facts about this humble, inexpensive, indispensable instrument:

More than 14 billion pencils are made globally every year—laid end-to-end they would circle the globe 62 times.

The average pencil can be sharpened 17 times and can draw a line 35 miles long or write 45,000 words—compare that to a ballpoint pen, which might cough up 1.5 miles worth of ink.

Pencils didn’t have erasers on them until about 100 years ago because teachers felt they would encourage mistakes.

The best quality pencils are made with cedar sheaths.

Despite the popularity of phones, tablets, and personal computers for writing, pencil sales in the United States increased 6.8% in 2018.

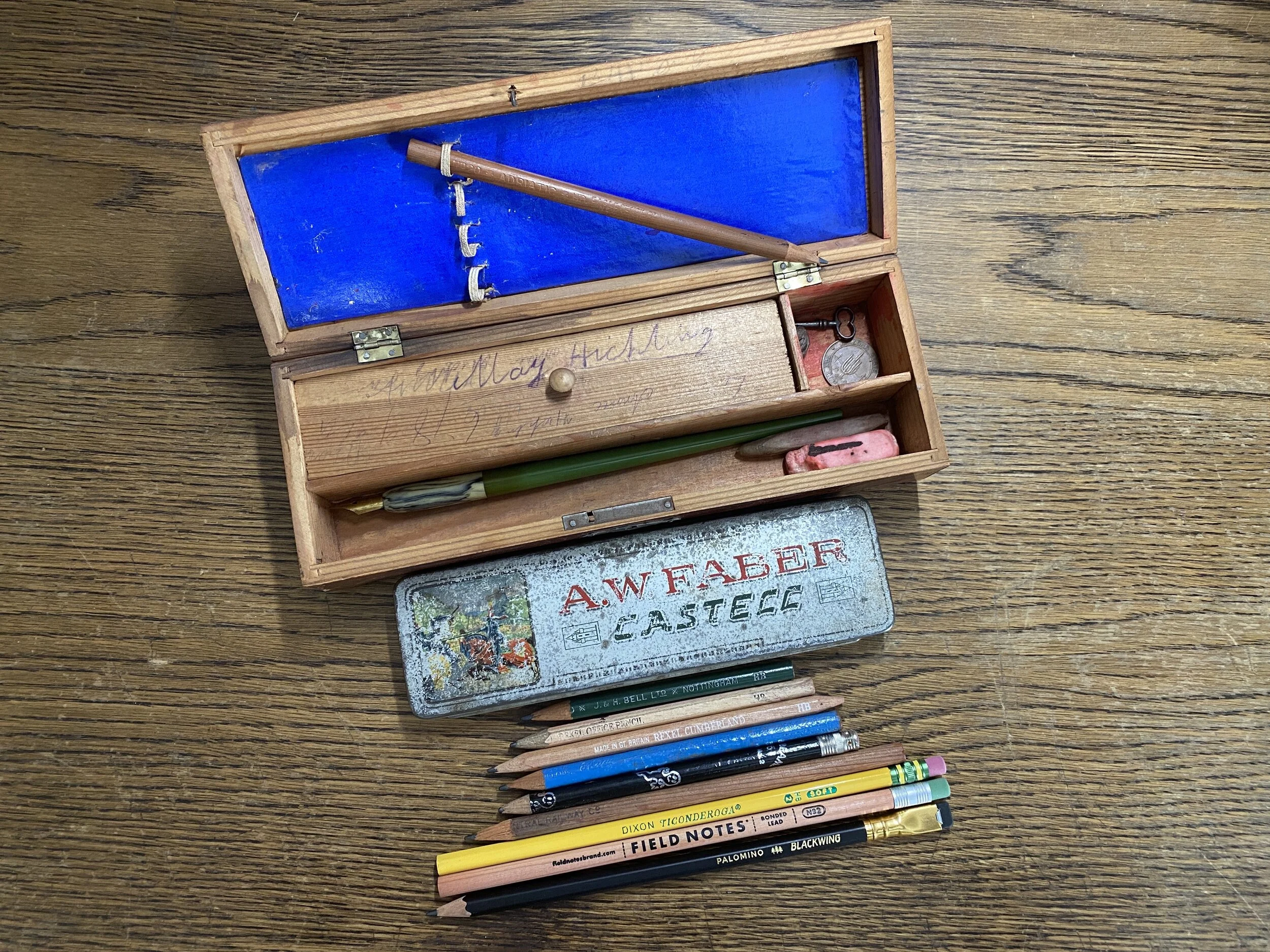

I found this wonderful wooden pencil box at a thrift store—and amazingly, the key was inside, along with several mummified erasers and half a dozen well-loved old pencils that date to around the time period of this box, which I estimate early 20th century (and based on the pencils, pretty sure from England). The Faber-Castell tin was also an earlier thrift store find.

Myth-busting: The interior of a pencil is not, nor has it ever contained, lead—although it’s called a “lead.” There are a number of reasons for this. First, one of the earliest writing instruments was the stylus or silverpoint, used throughout the Roman Empire to etch markings into wax tablets or to scribe dark marks on papyrus. The stylus was made from lead, tin, or silver.

What is inside pencils is graphite, a stable form of carbon (not to be confused with charcoal, which results from burning wood under low-oxygen conditions, called pyrolysis, and which humans have used over many thousands of millennia to mark on various substrates). Large deposits of very pure graphite were discovered in Cumbria, England, in the early 1500s. This was sawn into crayon-like sticks and used for writing, making writing instruments affordable for the first time. Because of its color and the fact it made a soft gray mark like a lead stylus, people thought it was lead and thus was it named. (The word “pencil” comes from the Old French pincel, from Latin penicillus, a “little tail”—also the same root for penis—which originally referred to an artist’s fine brush of camel hair, also used for writing.)

In the late 1500s someone had the brilliant idea to place the graphite inside wood sleeves and glue them together—which is essentially how they are still made today.

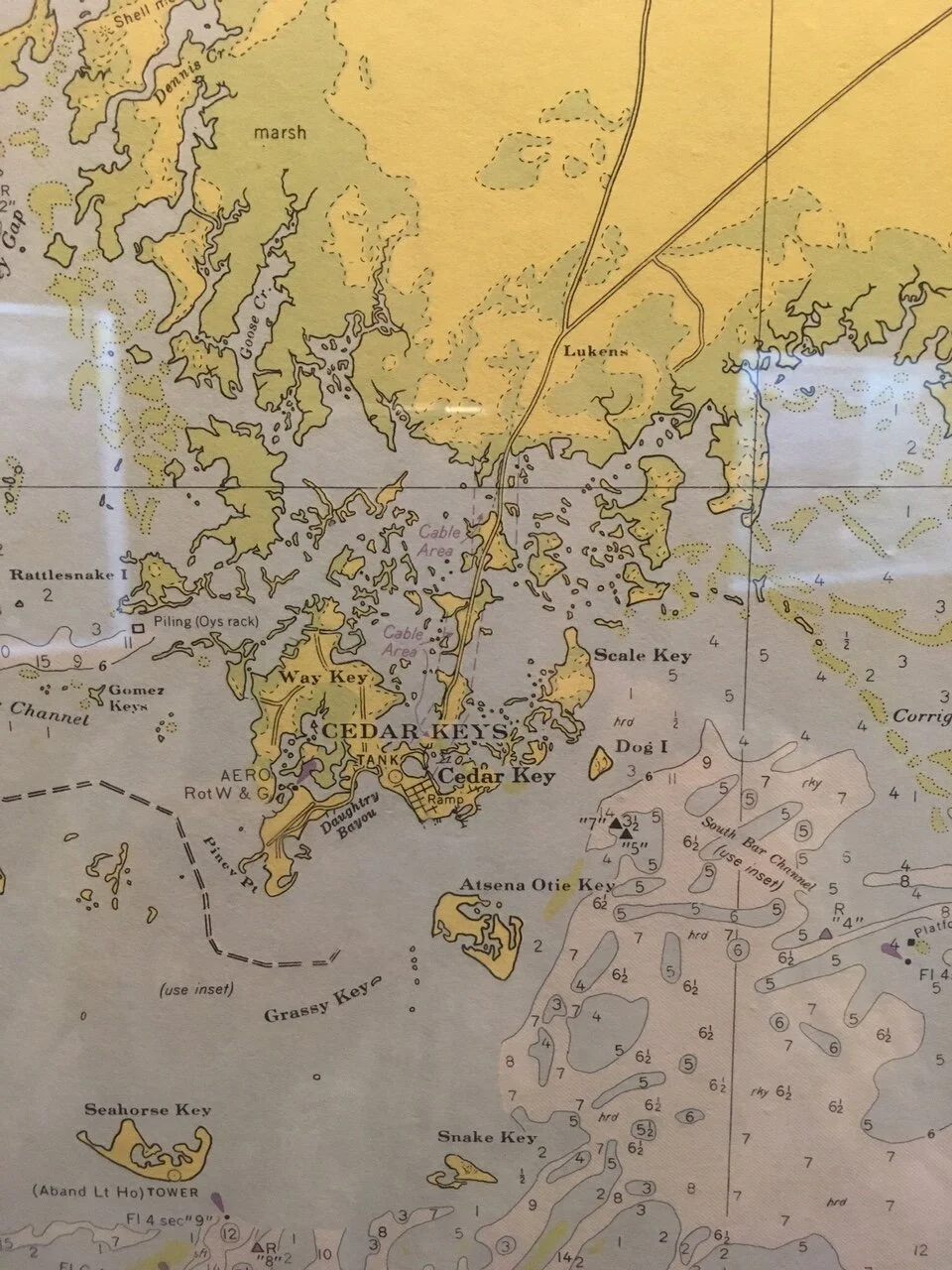

Many of the pencils made in the 19th and early 20th centuries had shafts made from cedar wood from Cedar Keys, Florida (and graphite from Siberia and England). One of my blog readers, Dorothea Malsbary, explored the region in 2019. The images above and below are from the Florida State Parks’ Cedar Key State Museum.

Compare the lower Faber-Castell pencil box with mine (photo at top).

Lineage of pencils, from top: green J & H Bell Ltd. (Nottingham, England); tan Rexel “Office Pencil HB” (Cumberland, England)—Rexel became Derwent and the brand is still made in England; unpainted Rexel Cumberland; blue F. Chambers “Universal No. ? HB” (Nottingham, England); black with silver ghosts J.R. Moon “Moonbeam 7851 No. 2 (Lewisburg, Tennessee); unknown maker, unpainted “Central Railway Company” branded pencil; new Dixon Ticonderoga No. 2 (Heathrow, Florida); new Field Notes Brand No. 2 (maker origin unknown; California incense cedar casing); new Blackwing 602 “Palamino” (originally made by Eberhard Faber Pencil Company; resurrected in 2007 by an independent company). Shown in second photo from top: Eagle Pencil Company “Adriatic No. 20 (pre-1969, England and New York).

The first six pencils in the photo, plus the Eagle, were all inside the wooden pencil box (see images at top).

Of note: Graphite was discovered in Borrowdale in England’s Lake District in the 1500s, which is why so many pencil companies originated there.

How to Sharpen a Pencil

In 2012 artist David Rees published How to Sharpen Pencils, a Practical and Theoretical Treatise on the Artisanal Craft of Pencil Sharpening for Writers, Artists, Contractors, Flange Turners, Anglesmiths, and Civil Servants. He is the world’s number one #2 pencil sharpener and shows us how to do so properly—the manual way. (See video, below.)

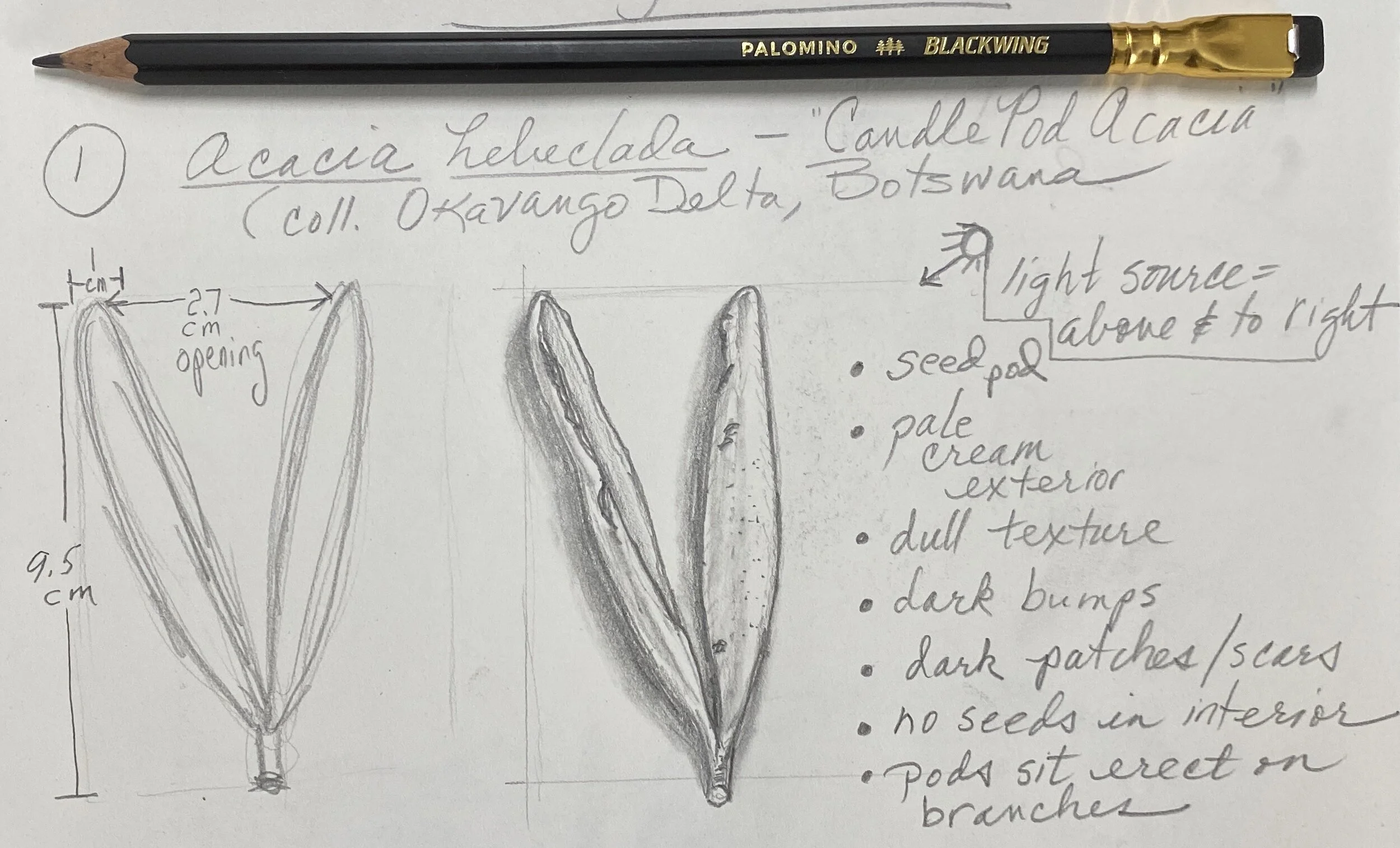

Grasping your pencil with your non-dominant hand, brace it against a table or log. Holding your well-sharpened bush knife in your dominant hand, steady the blade by placing your thumb on the spine and begin shaving off flakes of the cedar pencil shaft.

You want to aim for about a 2 cm-long cone tapering to the tip where the graphite will be exposed. Go slowly and shave small flakes at a time so that you don’t break out chunks or damage the graphite.

As you get down to the graphite core, expose about 5 mm, and then lightly shave the graphite into whatever point shape you desire (see below). You can get creative with the shape, for example a wide, flat chisel shape would be good for shading.

This is now the only way I sharpen all my pencils—it’s a revelation how much more useful a tip you can create, with much less waste.

Backstory on the Okapi knife: nearly every Maasai moran (warrior) and elder that I worked with in Kenya in the early 2000s when I was with African Conservation Fund carried one of these inexpensive folding knives, sold at every “Maasai market” in the country. The steel is 1055 hard carbon and takes a nice, sharp edge. The slipjoint Okapi was originally produced in 1902 in Solingen for export to Germany's colonies in Africa. The knife takes its name from the giraffe-like central African okapi, and today are made in South Africa. The Moorish-looking markings are enigmatic; I can find nothing on the current company’s website explaining the origin of the design. My Okapi is kept clipped to the outside D-ring of my field bag.