Three days on El Camino del Diablo

Few places on earth have experienced such a completely circular human history as the desert traversed by southern Arizona’s El Camino del Diablo. In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries its harsh plains and jagged mountains comprised a gauntlet for missionaries, explorers, and seekers of gold traveling northwest from Caborca to the first sure water at the Colorado River. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries it became another gauntlet, this time for illegal immigrants from Mexico and Central America trekking north seeking the gold of employment in the U.S. The tally of deaths from either period is impossible to pin down, but likely very similar. Some say each is in the hundreds.

Yet like many landscapes that have witnessed human tragedy, the magnificence of this corner of the Sonoran Desert transcends the strivings and failings of the bipedal creatures that scratch its surface. Here is a region where temperatures in summer regularly exceed 115 degrees Fahrenheit, yet where biological diversity is higher than in the pine-clad Rocky Mountains. Here lives a species of fish—found in just one spring-fed pond—that can survive water temperatures of 95 degrees and salinity higher than the ocean. The bighorn sheep that look down from the cliffs can lose 30 percent of their body weight to dehydration and survive with no ill effects. Within multi-holed mounds on the desert floor is a small rodent, the kangaroo rat, that never drinks or even needs to eat moist vegetation. It manufactures its own water from the carbohydrates in the dry seeds that comprise its entire diet. When winter rains are plentiful—meaning a few inches—the desert floor explodes in spring with a show of wildflowers to rival any English meadow. And always, always, the open space gives new room to lungs constricted by city living, and sharper vision to eyes clouded by concrete horizons.

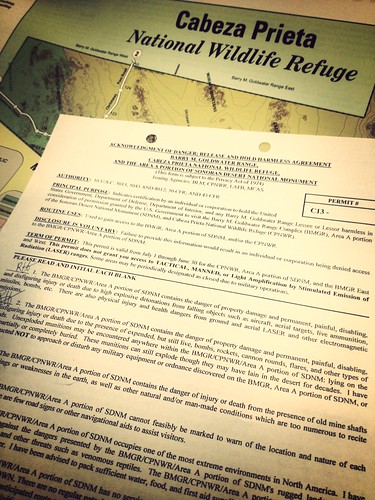

I first traversed "The Road of the Devil" in the sultry August of 1979, alone in my FJ40. In a week I saw not another soul—as far as I know, I had a million acres all to myself. That has changed, and although the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and the Barry Goldwater Air force Range, through which the road passes, remain remote and rugged, the U.S. Border Patrol now maintains a persistent presence, with two F.O.B.s (forward operating bases) plonked down surreally in the desert, and constant patrols. Before you can get a permit as a new visitor, you’re required to watch a 15-minute video and sign off on a hold-harmless form detailing at least 27 ways a stupid person could get hurt or be blown to smithereens in the area.

It’s worth it. The landscape along the main road from Ajo south and west through a corner of the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, across the Growler and Mohawk Valleys and the Tule Desert, is breathtaking, and changes with each pass through the mountain ranges—some dark, some light, some weirdly striped—that angle northwest/southeast through the refuge. The soft peach Pinta Sands dunes stand out in contrast to the surrounding lava fields, and improbable stretches of tightly overhanging mesquite trees mark the courses of washes that turn the road into impassible muck during summer thunderstorms.

The entire center section of the Camino is closed to public use from March 15 to July 15 to minimize disturbance to the secretive and endangered Sonoran pronghorn during fawning season—although the impact of the Border Patrol and migrants must be far greater than that of the few tourists who still brave the route. But if you wish, you can still drive in to the spectacular Tinajas Altas tanks from the west.

We beat the closure and spent a too-short weekend driving from Ajo to Tule Well, then north through Christmas Pass to Interstate 8. While some parts of the road are rough, and there are miles of corrugations north of Christmas Pass, we could have done the trip easily in a two-wheel-drive truck—or a sedan—in these conditions. West of Tule there are sections of bulldust that would challenge a low-clearance vehicle, however.

A four-wheel-drive Tacoma is almost overkill on El Camino. We're doing our best to abuse the stock street tires that came with the truck before mounting some all-terrain rubber.

A four-wheel-drive Tacoma is almost overkill on El Camino. We're doing our best to abuse the stock street tires that came with the truck before mounting some all-terrain rubber. Our first camp was at Papago Well, where a relief station and emergency beacon set up for migrants is marked with a blue flag.

Our first camp was at Papago Well, where a relief station and emergency beacon set up for migrants is marked with a blue flag.  Marisa stands amid the Pinacate lava flow, the northernmost extension of the Pinacate volcanic region. Near here is also the northernmost extension of the Altar dune field, called the Pinta Sands.

Marisa stands amid the Pinacate lava flow, the northernmost extension of the Pinacate volcanic region. Near here is also the northernmost extension of the Altar dune field, called the Pinta Sands. Looking down on Tule Well and the campsite (one of four on the refuge). The little cabin was built in 1989, replacing an earlier structure. A log book is inside for visitors to sign.

Looking down on Tule Well and the campsite (one of four on the refuge). The little cabin was built in 1989, replacing an earlier structure. A log book is inside for visitors to sign. Tule cabin is open and available for anyone to use if needed. There's even a small fireplace in the corner.

Tule cabin is open and available for anyone to use if needed. There's even a small fireplace in the corner.

Boy Scout troops erected this monument on the hill overlooking tule Well.

Boy Scout troops erected this monument on the hill overlooking tule Well.

Campfires are permitted, but you must bring your own wood. We also used a sturdy Snow Peak Pack & Carry fireplace.

Campfires are permitted, but you must bring your own wood. We also used a sturdy Snow Peak Pack & Carry fireplace. Dawn from Tule Camp. Mockingbirds and Phainopeplas were getting ready to breed, and singing.

Dawn from Tule Camp. Mockingbirds and Phainopeplas were getting ready to breed, and singing. Heading north through Christmas Pass, affording a fine view of our ultra-low-profile Global Solar photovoltaic panels, which provide the Four Wheel Camper with a surfeit of power.

Heading north through Christmas Pass, affording a fine view of our ultra-low-profile Global Solar photovoltaic panels, which provide the Four Wheel Camper with a surfeit of power. Under a cloudy sky we headed north toward I-8, past this enormous ironwood tree.

Under a cloudy sky we headed north toward I-8, past this enormous ironwood tree. Lots of unexploded ordnance on the Barry M. Goldwater range. This fin could be a piece, or there could be an entire missile under there. Do we pull on it?

Lots of unexploded ordnance on the Barry M. Goldwater range. This fin could be a piece, or there could be an entire missile under there. Do we pull on it? Federal law states that it illegal to visit the Cabeza Prieta without stopping at Dateland afterwards for a zillion-calorie date shake. Well, if it's not illegal, it should be. Support local business!

Federal law states that it illegal to visit the Cabeza Prieta without stopping at Dateland afterwards for a zillion-calorie date shake. Well, if it's not illegal, it should be. Support local business!

If you go: The refuge headquarters and visitors' center is in Ajo, on the road north out of (or into) town (Monday through Friday 8:00 to 4:00). You're required to obtain a free permit to enter the refuge, and will also need to register at a kiosk on the refuge border. The roads through the refuge are easily traversed, but a sturdy vehicle is recommended. You could drive the length in a day if you really wanted to, but it would be a wasted journey not to slow down and experience the scenery and wildlife.

Take plenty of water—there are no reliable sources on the refuge, and what's there is needed for wildlife. Take enough to ensure you could walk out to the nearest highway if necessary; don't count on a Border Patrol agent coming along to rescue you.

A fine book on the Camino del Diablo is Sunshot, by Bill Broyles.

View our entire collection of trip photos on Flickr, here, and our video highlights, below.