Pinnacle products: A white paper

“There are dinner jackets, and dinner jackets. This . . . is the latter.”

If you recognized the line—and, more important, if you smiled and nodded approval—then I don’t need to introduce you to the concept of a pinnacle product. But on the slim chance you aren’t a Bond movie fan, let’s talk.

It’s axiomatic that the overwhelming majority of consumer products have to be compromises.

This is because, above all, a product has to sell to be successful, to earn a profit for its maker. Thus function, performance, weight, ergonomics, style, durability, reliability, sustainability, fair labor practices—a hundred parameters—might each be considered and incorporated to lesser or greater degrees depending on how much it costs to include each one—or perhaps rather how much profit it takes away. And generally a product that includes all of them simply costs too much to produce and offer at a price most consumers will (or can) pay.

But for a scant few products, a scant few manufacturers through the years have chosen to throw this paradigm out the window. Those manufacturers ignored their accountants and made the product the best they could possibly make it—and figured out afterwards how much they needed to charge for it to make a profit.

Sometimes this bold approach works; other times it does not. Consider, for example, the 1992 McLaren F1—still considered by most automotive experts to be the finest supercar ever produced. The designer, Gordon Murray, overlooked not a single detail to make the F1 the best it could be. Components as seemingly unimportant as the throttle pedal had days and days of design input and were made from the finest and lightest materials available—then remade again and again until they were perfect. The exhaust heat shield was gold foil, because gold reflects heat better than any other metal. The proof of the F1’s brilliance came when a barely modified example won the 24 Hours of Le Mans outright. Twenty eight years later the F1’s 242 mile-per-hour top speed has not been topped by another naturally aspirated vehicle.

And yet. McLaren planned a production run of 300 F1s—but only 106 were ever made. It was ahead of its time, and it was exceptionally expensive: $800,000. By comparison a 1990 Porsche 959—a pinnacle machine of its own—ran about $300,000 (although it’s thought Porsche lost at least $200,000 on each one it sold).

So producing a pinnacle product is clearly a risk, even if it is considerably less expensive than that F1.

A pinnacle product does not have to be the best at everything; it simply needs to be the best at what the manufacturer wanted it to be. The early decades of Rolls-Royce motor cars exemplify this. The first Silver Ghosts weren’t intended to be high-performance or even particularly luxurious. They were built to be supremely reliable and durable, and they were, winning numerous reliability trials, and leading an outside source—The Autocar —to proclaim the Rolls-Royce “The world’s best motorcar,” a slogan the company quickly adopted. In fact the early Rolls-Royces were reliable and durable enough that they went to war, serving with T.E. Lawrence in the Middle East and modified with armor for other campaigns.

A pinnacle product can be a classic—that Silver Ghost, or the Wehrmacht jerry can, for example—but a classic product isn’t necessarily pinnacle. The original Land Rover essentially defines classic in the world of expedition vehicles, but it was built within numerous cost-cutting parameters, chiefly due to the rationing of steel and the extreme economic difficulties faced by the Rover company and England in the late 1940s. The box-section chassis, for example, was an elegant solution to the need to reduce the amount of steel in each vehicle while retaining adequate torsional rigidity, but the material was necessarily thin and thus very prone to rust issues, and for reasons of cost was never galvanized—a compromise that endured through the end of production in 2015.

A pinnacle product can be eclipsed in performance by a later product that doesn’t qualify as pinnacle, simply because technology advances to the level where even less-than-pinnacle technology is better than what came before. It’s undeniable that a modern DSLR camera produces higher-quality images than could be produced by a 35mm 1954 Leica M3. But the M3 (another example of a product both pinnacle and classic) was made with single-minded attention to craftsmanship and durable function. Today’s cameras, however well-built they may be, are constructed with the secure knowledge that they will be outdated within five years. No modern DSLR will be held in the same regard 60 years from now as the Leica is.

Pinnacle products do not necessarily have to be expensive items, although in virtually all cases they are among the most expensive products of their type. I’d consider Snow Peak’s double-wall titanium coffee mug an example of a “budget” pinnacle product, and at $50 it’s attainable—but a perfectly serviceable stainless substitute can be had for a fifth the price.

I’ve decided to start a new, occasional entry on Overland Tech and Travel, nominating and telling the story of a product I view as pinnacle. Most will have at least something to do with overland travel, but not necessarily—some might just be interesting.

These stories won’t be simply slavish homages to absurdly expensive consumer products. Many times the technology or materials that are introduced or proven in pinnacle products subsequently trickle down to more affordable products. Thus it’s worth investigating the former even if you think the idea of spending $50 on a coffee mug—or $800,000 on a car—is insane.

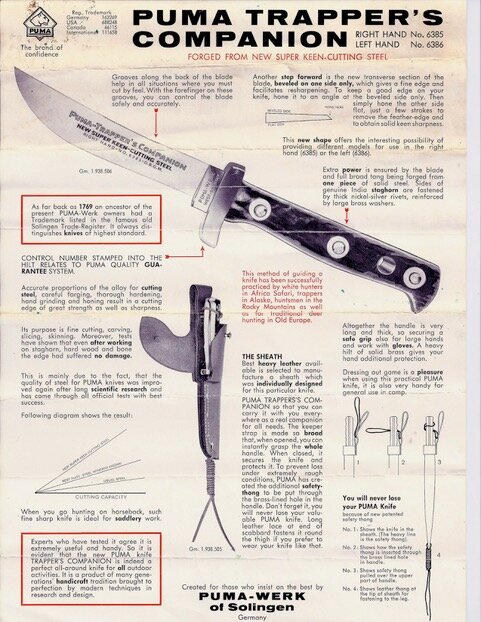

Also, I believe any pinnacle product should above all serve a purpose and be used for that purpose. Consider, for example, the knife pictured above. It was my introduction to the concept of (and, okay, obsession with) pinnacle products.

As a teenager itching to spend yard-work money on my first real knife, I pored over the usual Field and Stream ads for Buck, Schrade, and Western—but with my first look at an ad from Puma, I knew there was something different about them. Even in black-and-white the superior fit and finish was obvious. They were forged in West Germany, individually serial-numbered. The scales were Sambar stag, not plastic or jigged bone. Every Puma knife displayed a tiny indent on the blade where the steel’s correct hardness was confirmed with a diamond point. (You can see it here just off the corner of the “P” in Puma.)

Even among the various beautiful Puma models there was one that jumped out at me. It was called the Trapper’s Companion—the very name whispered of wilderness adventures. It had the most beautiful lines I had ever seen on a knife: The blade showed the even, perfect sweep of a saber, or the sheer of a sailboat. The blade was bevelled on one side only—something I’ve not seen since in a knife—and thus could be ordered in right or left-hand configuration. For a left-handed kid this made it all the more entrancing.

Even the sheath was special—a full-length, protective leather cover with an embossed puma head, and a leather thong that threaded through a hole in the knife’s handle to secure it against loss.

Puma produced a full-page information sheet for the Trapper’s Companion, including exhaustive descriptions of each feature—which I memorized down to the last detail.

Image courtesy pumaknifeman.com

There was just one problem. The Trapper’s Companion cost an astronomical $32—at the time when a Buck Personal was $14.

So, bowing to teenage economic reality (and impatience—my best friends already had good knives), I bought the Buck. And it was a fine knife. And meanwhile, my pinnacle knife, the Trapper’s Companion, did not sell well at its premium price, and was soon dropped from the importer’s catalog.

But I never forgot about it. I never threw away the ads I had cut out. And decades later, I found a Trapper’s Companion in fine condition on eBay, and paid somewhere around, er, ten times its original price for it. You could easily imagine I then put it on a shelf to admire, but I’ve field-dressed deer and elk with it. I wish I could travel back in time to visit that teenaged me and show him.

I’ve been accused more than once of being a snob, or elitist, or at the very least too attached to the idea of having stuff. I maintain my philosophy is almost exactly the opposite. That early penury drove home to me the real value of high-quality equipment that lasted longer and was thus actually cheaper in the long run than products that cost less to begin with. In 1983 I bought a Marmot Grouse sleeping bag that was insanely expensive at the time—a true pinnacle product sheathed in cutting-edge Gore-Tex and stuffed with the best goose down available. Thirty seven years later that bag is still in perfect condition and has lost at most a half inch of loft. Who knows how many fiberfill bags I would have used up and given away over the same period? My SVEA 123 backpacking stove is ten years older than that; I think it’s earned its steep $12 price several times over.

So there’s my introduction to and explanation of the new series, along with my first pinnacle product. Much to come. If you have any suggestions I’d be happy to consider them.

Even if it’s a dinner jacket.

(Postscript—tragically, the Puma company changed hands twice in the 1980s and 1990s, some production was moved out of Germany, and quality overall plunged. The pinnacle era of the Puma Knife Company was over. Older Pumas now command a substantial premium. See some really fine ones here.)