Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

An odd winch bumper

I’m always on the lookout for inspiring—or horrifying—modifications and accessories on the four-wheel-drive vehicles I spot anywhere in the world. But this curious example was right here in Tucson.

I’ve written many times about the critical need to have visual and tactile access to the winch drum, and if this Jeep actually had a winch mounted to the bumper the operator would certainly have that access. But the plate securing the roller fairlead stumps me. For the life of me I cannot figure out the point of having it angled the way it is. The best wild guess I could come up with is that it vaguely mimics the look of the “stingers” so popular in a certain segment of the 4x4 community; however, it certainly wouldn’t function as one, and looks to me like it would hamper the function of the fairlead.

With no winch mounted it’s difficult to be certain, but it appears the winch line would skim the bottom of the cutout for the fairlead very closely indeed when the drum was full. Since the side rollers are angled, a side pull would result in the line partially dragging on the roller, reducing its effectiveness—a minor flaw to be sure, since given a hawse fairlead the line drags all the time. However, on a steep uphill pull (a common winching scenario) with a side pull factor thrown in, the line would be at a very steep angle near the top of the side roller.

Finally, on a general note: While I’m no welding expert, the bead along the winch plate and fairlead plate is really sloppy, and looks as though it might be lacking adequate penetration as well.

An odd winch bumper, to be sure.

Smittybilt "Recovery Strap"

Before last year’s Overland Expo West, as we were juggling trucks and trailers and various four-wheel-drive vehicles to make sure we had all the transport and training equipment we’d need in Flagstaff, Roseann mentioned that we should have a basic recovery kit—a Microstart and a recovery strap—in every vehicle. Of course our main travel vehicles already had full kits to go with the winches on them, so I went online and found some inexpensive (Chinese-made) but brand-name “recovery straps” from Smittybilt. I tossed one in each of the spare trucks.

This morning, for the first time, I took one out of its cellophane wrapper, and was incredulous at what I found.

Nowhere on either the paper label or on the strap itself does it indicate whether this is a kinetic recovery strap or a non-kinetic tow strap. The only mention of materials is the note that it has “ballistic nylon reinforced ends,” which of course says nothing about the composition of the strap itself. Elastic nylon or non-elastic polyester? The paper label claims the two-inch-wide strap is rated to 20,000 pounds. Nowhere on the strap itself does it indicate this, or whether that rating is a working load limit or a minimum breaking strength. The sole scant indication of intended use comes all the way down the list of characteristics on the label, a line that says simply, “low stretch.” Does that mean minimal stretch, as one needs for a tow strap, or low stretch as in it will stretch if used kinetically, but not a lot?

My conclusion is that the Smittybilt “Recovery Strap” is actually a non-kinetic tow strap. But the lack of solid information, especially regarding the composition of the strap, and its advertisement as a “recovery” product, could effortlessly lead a consumer to employ this in a kinetic situation, with potentially disastrous consequences.

This is a bad, bad effort on Smittybilt’s part.

If you’re shopping for a tow strap or a recovery strap, make sure what you buy lists clearly its:

Precise intended use—towing or kinetic recovery

Materials—stretchy nylon or non-stretchy polyester

Working load limit (WLL) or minimum breaking strength (MBS)

And make sure all this information is on a durable label on the product itself.

Don't risk "Gargo damage." And note that "Strenght" could be reduced . . .

A bad, a really bad, winch mount

As I’m sure many of you do, I like to look at how others have set up their vehicles. I’m always impressed by clean and functional work.

Sometimes I’m impressed by the opposite.

This truck was parked at a hotel in Eagar, Arizona, last winter when I was there hunting. It sported one of the dodgiest looking winch mounts I’ve seen in years. If this thing doesn’t wind up starring in a YouTube video someday featuring large bits of metal taking murderous trajectories across the landscape, I’ll be stunned.

I couldn’t even actually tell how all the bits of the “mount” had been welded together to gain a tennuous foothold on the chassis, but one weld at the back appeared to have pulled free. The winch itself was bolted to a plate welded to a male receiver hitch insert. I’m not sure if the droop was the result of forces incurred while (wince) actually using this thing, or if it just wound up at that angle after all the welding was finished. The steel cable was pulled under the winch and hooked on the back of the plate. Lettering on it read, “HI-TEST.” Yeah, I’ll bet.

Since it was mounted in front, I don’t think I can hope this thing is only used for pulling ATVs up on trailers. I just hope the owner’s survival instincts are better than his fabrication skills.

I don’t make fun of the owner/fabricator whose only sin is being an overenthusiastic beginner. But potentially life-threatening jobs such as this need to be called out.

Bespoke sand ladders

I didn't get a chance to inspect closely—or try—these compact aluminum sand ladders that my friend and 7P/Overland Expo trainer Nick Taylor had welded up and brought to the show, but I like the concept. It's no secret that I'm a fan of Maxtrax (on the left), but in certain situations a rigid aluminum (sorry Nick, aluminium) ladder has advantages, especially for bridging.

This pair is amazingly compact, and Nick had them made slightly different in size so they nest.

Given their abbreviated length, getting out of anything but a short bogging would require repeated deployment, but most boggings (except those in mud) can be overcome with a very short extra bit of traction or flotation. And these would be excellent for bridging a small ditch or climbing a ledge.

I'm thinking about finding an alumin(i)um welder in Tucson and having a pair of my own made.

Bogert Manufacturing wheel chocks

Chocking your vehicle’s tires is one of the most basic and critical safety procedures you can follow before changing a tire, winching, or working underneath it. Yet how many of us ever use anything but nearby rocks or logs to do so? Not only are you at the mercy of what’s available (Will this work, or do I need that bigger one over there?), but if you happen to be leading a trip or are otherwise in a position of some assumed authority, it lends a rookie taint to your otherwise faultless command presence to be seen looking around for rocks.

I thought about this recently while looking around for rocks.

To make matters worse, I had a good set of chocks with me—the clever folding units made by Land Rover—but they were inconveniently stashed in a compartment under the rear jump seat of the Tacoma, which itself was under several layers of Pelican cases. So I took the lazy route.

Lessons learned: a) Have stuff like this easily accessible, and if it isn’t, b) Follow Graham Jackson’s First Rule of What to Do When There’s Trouble, which is, Slow down and brew a cup of tea, and then Jonathan Hanson’s First Rule of What to Do When There’s Trouble, which is Use the right tools. Sorry Graham. And me.

As much as I like the Land Rover chocks, their lightweight, folding construction pretty much relegated them to tire-changing and working-under duties. Thanks to the fertile mind of Richard Bogert of Bogert Manufacturing, I now have a set of heavy-duty, winching-compatible chocks.

Constructed of 3/16ths-inch steel and heavily powder-coated, the Bogert chocks take up virtually no more room than the folding ones if you stand them on edge in the corner of a cargo box. A set of them comprises not two but, properly, four, so you can anchor two wheels on both sides, or four wheels on one side if you’re on a hill. Additionally, a set of holes and slots in each chock allows you to chain two together on either end of the wheel to prevent shifting if the truck jerks back and forth under a load—nice. Each set of chocks comes with four chains, so you can anchor each pair of chocks on the inside and outside of the wheel if needed. The result is one solidly immobile truck.

The set is now stored in the “Camper Setup” Wolf Pack box that rides just inside the door of the JATAC's Four Wheel Camper. So accessing proper chocks will be as easy as picking up a rock, and my faultless command presence can remain intact.

From now until the end of June, Bogert is offering a 15 percent discount on all their superb recovery tools and accessories. Please use code K7E. Bogert Manufacturing is here.

The Micro-Start XP-1

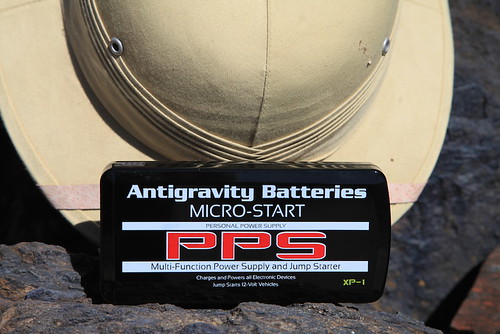

Experienced mechanics don't often sound giddy over the phone, but Dave Anderson sounded giddy when he called me from his Flagstaff, Arizona, shop, the Good Carma Garage (which really should be a radio program).

“I just bought this thing off a tool truck, and you have to get one,” he said, “You’re going to think it should be on every overlander’s equipment list—even before he buys a pith helmet.”

Dave. Such a kidder. As it happens, I own a pith helmet. And not one of those fake ones made from cork or, worse, styrofoam, either (I won’t even mention Graham’s mesh thing)—mine is a genuine pith helmet made in Vietnam from the pith of the Aeschynomene aspera, or sola plant (one of the original names for the helmet, sola topee, was later corrupted to solar topee). While they’re now little more than a Hollywood cliché, pith helmets are eminently practical—the thick fibrous material offers exceptional insulation from the tropical sun when touring one’s tea plantation or stalking a man-eating tiger with a Rigby.

Where was I? Oh, right: At Dave’s insistence I ordered a Micro-Start XP-1 from Antigravity Batteries. The zippered pouch that arrived three days later was no bigger than a calendar/day planner (remember those?). Inside was a bewildering array of adapters for charging various electronic devices from phones to laptops, and an astonishingly lightweight (15 ounces), 225-amp-hour lithium/ion battery, just one by three by six inches, which, incidentally, can also be used to jump-start your truck.

Say what?

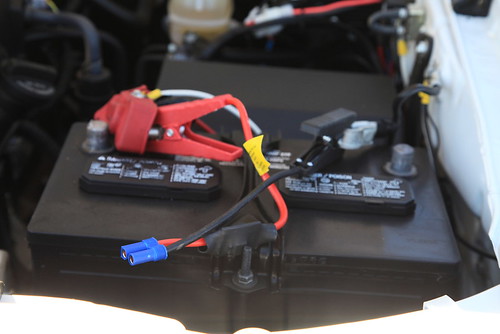

It’s true. The pouch includes a set of battery-post clamps, and the company claims the power pack will start a V8-engined truck—not once, but several times.

Could this mean the end of jumper cables? I’ve always hated those things, and especially I hate what happens when I play good Samaritan to jump some poor bloke’s dead Malibu—in trying to help he always wants to grab the cables and hook them up in the wrong sequence—if not to the wrong terminals. I have to come off as a tyrant just to do a good deed. With the Micro-Start I’d be in complete control of the situation. And of course if your own vehicle becomes stranded you are completely removed from the need for a donor vehicle—handy if the nearest candidate might be 40 miles away.

The instructions for jump-starting a vehicle tell you to hook up the terminal clamps to the dead battery first, then plug the siamese fitting into the power pack. The reason for this is that, while the teeth of the clamps are well-surrounded by plastic, it would theoretically be possible to screw up and touch them together, resulting in the same alarming pop and flash you get when you do the same thing with jumper cables. If you were really determined and managed to clamp the teeth together, a puff of smoke would signal the death of your power source. I found it easy to remember to hook up the clamps first and then attach the battery, and virtually impossible to remember to unplug them first and then undo the clamps after use. But I never shorted anything.

Hook up the terminal clips first, then plug in the power pack.

Hook up the terminal clips first, then plug in the power pack.

So how well does the XP-1 work? I disconnected our Tacoma’s battery to give it a try by clamping the leads directly to the battery cables. I wanted to video the process, and while setting up the camera I simply stashed the XP-1 battery in my back Levi’s pocket—it really is that small.

You can find more torturous demonstrations online, but the initial trial on the Tacoma went thusly:

It was impossible to detect a difference between the XP-1 and the way the truck fires with its own battery. I started it three times in a row with no trouble at all, and there were four blue LEDs left out of five on the battery’s charge indicator. Clearly there’s not only sufficient amperage inside that little brick to turn a V6’s starter motor, but to do it multiple times.

As impressive as that demonstration was, it simply confirmed the maker’s claims. Looking around for an unfair test, my eyes alighted on our 1985 Mercedes 300D turbodiesel. To start that the XP-1 would first have to power the glow plugs, then turn the hi-amperage starter necessary to crank a five-cylinder engine with 18:1 compression. After recharging the power pack and removing the cables from the 300D’s massive battery, I hooked up the XP-1, and:

Okay, so that was a bit too much to ask. (Scot Schafer at Antigravity Batteries confirms that they have a model in the works that will be configured for the much tougher task of starting diesel engines.) Rather alarmingly, there were no blue LEDs left on the charge indicator after the Mercedes experiment. Had I killed this thing 15 minutes after first deploying it? I plugged in its 120-volt charger (there’s also a 12-volt car adapter)—and an hour later it was back at full charge. It’s a resilient piece of equipment.

If your vehicle is powered by anything up to a 400-cubic-inch gasoline V8, the XP-1 will provide you with ample starting capability. The battery will retain its charge for many months at a time; if you remember to give it a top-up every half year or so you should be pretty much immune to becoming stranded due to a bad battery. And think of the effect on the owner of the dead Malibu when you start his car with a magic box the size of a paperback. It might be a good idea to keep a few XP-1 kits in the truck to sell at an exorbitant profit . . .

The XP-1 is a bargain at around $140. A basic model, the XP-3, sans the adapters for personal electronic devices, is available for about $30 less. AntiGravity Batteries is HERE.

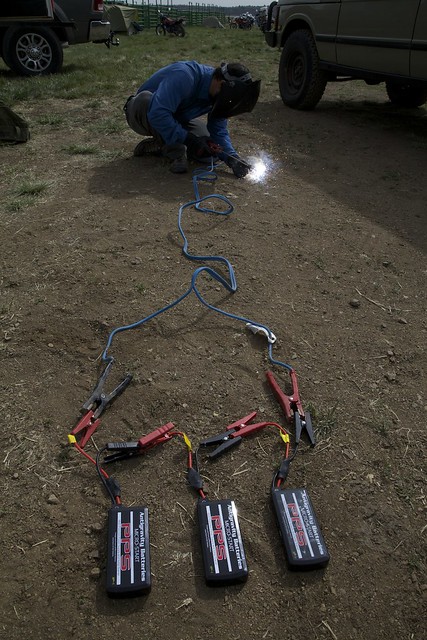

An update: While discussing the Micro-Start as we were setting up the Overland Expo, Graham Jackson, Tim Scully, and I started musing on whether one could weld by hooking up three of them in series. Taking a chance that we'd blow all three units we owned, Tim hooked them up, connected cables and a welding rod—and produced a perfect bead connecting two pieces of 1/4-inch steel. We were gobsmacked. We then hooked up two of the units to my Redi-Welder DC wire-feed unit, and again got a perfect result.

Obviously this is not something endorsed by the maker, and would quite rightly invalidate your warranty. But it showed what would be possible if a weld repair might make the difference between walking and driving out of a remote location.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.