Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

African trail hazards

The offending limb

It was Connie who alerted me, in her inimitable style, as we stopped at the entrance gate to the Moremi Game Reserve to pay the entrance fee.

“Jonathan,” she said, deadpan, “You have a stick up your butt.”

I realized even without checking that she was speaking metaphorically, so I looked at the next obvious spot—the rear of our Troopy. And there it was: a pretty stout limb as a matter of fact, wedged somewhere firmly in the vehicle’s undercarriage and dragging on the ground. Wedged so tightly as to be scoring an impressive furrow behind us. I was pretty sure I’d heard it get there, but the forest track we had followed had been littered with such limbs of various sizes, and I’d gotten used to the odd one smacking the undercarriage when a tire flipped it. The strategy with such limbs lying crosswise is to drive over the middle if possible, as this reduces the chance of flipping, but it wasn’t always possible, and many of the limbs were concealed in undergrowth.

A glance under the truck showed the limb angling up to the rear axle, where it took an abrupt bend in front of the tube and up into the chassis. I got down and slid under the Troopy, gave a yank on the limb, and . . . nothing. It was well and truly jammed in there. So I slid in all the way, and found that the end had somehow crammed its way past brake, water, and diff-lock lines to lock itself behind a frame crossmember.

And then I noticed the sheen of some sort of liquid. Uh oh.

I could see the water line from our chassis-mounted tank, and it was intact. My next, worried thought was brake line. But the brakes had felt fine as we stopped. By now Graham had crawled under as well, and said, “Gear oil.” We smelled it and sure enough. The stick had ripped off the air line fitting for our ARB diff lock, and severed the line itself. Some differential oil had come out with it.

It took some serious heaving to free the end of the limb and remove it—I’m still mystified as to how it managed to insert itself that firmly in a fraction of a second. There was no way to repair the line—it was now too short and the fitting was mangled. So Roseann found a wood skewer of the approximate inside diameter as the fitting on the diff housing; I cut a short plug from it and used Gorilla Tape to securely fasten it in place.

We drove the rest of the trip through Botswana and Namibia with the bandage in place. There was no more leakage, so the truck went into its shipping container that way. I’ll fix it properly when it arrives in Arizona. (I’ll check carefully to make sure no oil is being pumped up the air line toward the compressor, which can happen in certain circumstances with ARB lockers.)

I only forgot about the issue once, on the challenging track we took from Twyfelfontein to the Ugab River Canyon. I paused before a short but very steep and loose climb and, without thinking, hit the compressor switch for the locker.

“Uh, watcha doing?” Roseann asked. Oh, right. Of course we made the climb with zero drama and no locker.

In this case I don’t feel that I did anything wrong driving-wise, and I don’t feel that I was remiss in not having spare air line and fittings along. You just can’t predict everything. I did learn, however, to pay attention when Connie Rodman says there’s a stick up your butt.

And the damage

Driving among elephants

If you are as lucky as I am, you might someday get to drive your own vehicle in Africa. If you are very lucky, you might get to drive that vehicle close—sometimes very close—to African elephants. How you behave in that situation might determine whether or not your vehicle remains in its preferred position with all four wheels on the ground.

I’ve not only been lucky enough to drive close to elephants, but to have done it dozens of times, to have led others driving their own vehicles close to elephants, and, before that, to have been driven close to them. This, combined with (much more valuable) advice from biologists and guides with decades more experience than I, has imbued me with enough pachyderm politeness that—so far—my presence has been tolerated with no sudden 90-degree shifts of the horizon. But a quick search on YouTube will reveal others either unlucky enough or, more often, stupid enough to piss off the animal—and a full-grown African elephant is quite capable of toppling and/or trashing a heavy expedition vehicle.

The first thing to know is that the elephants you’re likely to see from a vehicle are probably quite used to seeing vehicles, and normally will virtually ignore them as long as those vehicles stick to predictable behavior. It’s when the vehicle does something unexpected—diverging from a known track, moving too quickly, approaching too closely, getting between members of a herd, or appearing unexpectedly—that the elephant’s alarm bells go off. It follows, then, that when piloting a vehicle around elephants you’ll want to stick to known tracks, drive slowly, keep distance between you and the animal, stay out of the middle of herds, and avoid surprising them. You’ll also want to avoid making loud noises—honking your horn to alert your friend in another vehicle that THERE ARE ELEPHANTS RIGHT HERE! is a no-no. And turn off your camera’s flash.

If you’re on a game drive and spot a group of elephants browsing, and want to get close enough for better viewing or photographs, the best strategy is to let them approach you. Slowly maneuver to get 50-75 meters in front of what appears to be their path, stop, and wait. You can leave the engine idling or turn it off—I’ve never had it affect the elephants’ behavior either way—but leaving it idling gives you a less intrusive option for slowly retreating if it seems necessary. If they come close, great; if not, don’t punch it in an attempt to head them off. Wait and circle around after they have passed.

If you’re on a track and come up behind an elephant or elephants heading the same direction you are, you can slowly close the distance, but watch very carefully indeed for any signs of discomfort or annoyance—elephants don’t like to be tailgated any more than you do. On the other hand, if you come around a bend and find an elephant walking down the road toward you, don’t just stop; pull off to leave it room to take the easy path.

One common situation I’ve come across causes trouble surprisingly often. An elephant will be standing next to a road, either simply loitering, or musing on whether to cross and try that tasty acacia he sees yonder. However, even though he’s not moving, I’m absolutely convinced that elephant has already laid claim to the crossing. Numerous times I’ve watched a vehicle stop and wait for a minute, then try to ease past, and more often than not this results in an immediate flaring of ears, shaking of the head, and an annoyed trumpeting if not an actual mock charge. It’s tempting to anthropomorphize and think this baiting game is a popular elephant pastime, but in any case it’s better to just wait until he makes up his mind.

Speaking of charges: I first remember reading about the differences between a mock charge and a real one in an early book by a professional hunter. He described the mock charge as “ears out wide and flapping, trunk straight down, lots of head-shaking and trumpeting and stirring up dust, but brought up short of any real confrontation,” while a real charge was, “ears flat against the head, trunk tucked up underneath, no noise, just a shockingly fast rush at the offending object that would only stop when that object was flattened or gored.” I’ve only seen a single real charge, at a rapidly retreating safari vehicle that had tried the “squeeze past” maneuver (it escaped), but lots and lots of mock charges that fit the old hunter’s description perfectly and ended with nothing but a truck full of wide-eyed tourists and some really good photos. With that said, it would be utterly stupid to treat any charge by an elephant as a harmless show of bravado. I recently watched a video of a “mock charge”—ears out, trumpeting, the works—that ended with the elephant’s head impacting the side of the vehicle hard enough to tilt it significantly and induce screaming in the occupants and a precipitous retreat by the driver.

This elephant objected to us driving slowly past, obviously because of the young one behind her.

The other thing to remember is that an elephant can be a dangerous animal even when it’s not trying to be. I watched another video, taken from inside an open 12-seat safari vehicle, of a large bull elephant that slowly circled the vehicle three or four times only a few feet away, giving the forest of brandished phones and cameras inside a great show. Eventually he stopped, gently placed his head against the rear corner of the Land Cruiser, and pushed. The vehicle rocked on its springs and the occupants squealed delightedly. Then he pushed harder, and the occupants stopped squealing. Harder yet again, until it looked like the near-side wheels might be coming off the ground. At that point the driver abruptly took off, while the elephant just watched the retreating machine calmly. He clearly had no ill intent; he was just curious and playful—but that would have been irrelevant to the people inside the vehicle if it had turned over.

While I’ve had no such close calls, Roseann and I did have a hilarious episode on our last trip. We were driving along a track in Chobe National Park, heading toward Savuti Camp and pushing it just a bit to make it before sundown, with Graham and Connie a half kilometer or so behind us. It was a single-width track running through dense mopane forest about three or four meters tall—the astute among you will note this is more or less exactly elephant height. There was no sound but the calm rattle of the 1HZ diesel—until there was a deafening scream about two meters from my right ear, and an elephant crashed back into the brush from where it had been standing, completely invisible, almost in the road. I believe Roseann and I both might have made our own elephant noises. Fortunately the elephant left rather than sticking around to take revenge on the next Land Cruiser to come along, as Graham and Connie never saw it.

Most of our encounters on that trip were far less coronary-inducing—such as driving up to an unoccupied elevated hide (blind in U.S.-speak) by a waterhole with no wildlife in sight, having lunch, and being just about ready to move on when two, then six, then twelve, and finally sixty four elephants showed up to drink and bathe in the mud. A transcendent experience.

As we all know, elephants are facing an existential threat due to the rampant poaching trade, which does nothing but supply wealthy Asians with status-symbol trinkets and coffee-table sculptures. Income from tourism does at least some good in the fight against this despicable perversion of human greed, and encourages the countries involved to continue fighting. Thus driving among elephants is both a humbling personal experience and a valuable contribution to their future.

Just keep in mind the rules of the road when you go.

Elephants always have the right of way.

Routines . . .

Routines are important when you are on the road in a strange country. They help maintain a sense of solidity, familiarity, and comfort when much of your day might be spent route-finding and driving in difficult terrain, provisioning in towns where English might be spoken little if at all, or dealing with bureaucracy-choked border crossings.

The routines don’t have to be the same ones you have at home—which is often impossible anyway—they just have to offer a grounding for the day. And the more of a habit you make of them, the more of a grounding they provide.

Lots of people start out the morning with coffee, of course: the grounding routine of all grounding routines. But how you go about it can be its own routine. My friend Graham Jackson invariably starts the pre-dawn day by collecting twigs and boiling water in one of his growing collection of volcano kettles. In fact one of my own grounding routines is simply seeing that plume of smoke rising into the still air while Graham watches with his hands clasped behind his back. Roseann and I use a volcano kettle as well, but only for our later, mid-morning coffee. At first light we’re too impatient to wait until we’re up and fully clothed to get the water going, so we put a standard kettle on the stove inside the camper while we dress. We might wind up with our coffee in hand a bit sooner than Graham, but I suspect his is more satisfying.

Graham also starts the day with rusks to be dipped in his coffee—a routine that must be particularly comforting given his upbringing in South Africa. We like them too, when we can find them in a bakery, as we did these superb versions in a coffee shop in Windhoek.

We generally skip breakfast, but make up for it with another regular treat: bacon and egg sandwiches at a mid-morning halt, either prepared then (while boiling water for coffee in the volcano kettle), or fixed ahead of time, wrapped in aluminum foil, and then re-warmed on the engine block when we stop. On the Troopy we carry the gas (propane) bottle on a swing-away on the Kaymar rear bumper, and we have a burner that screws directly to the bottle, so setting it up to use a frying pan is quick; we leave it right on the mount. A Front Runner drop-down table on the Land Cruiser’s rear door serves perfectly as a prep station.

The protein-rich sandwich provides plenty of fuel for the mid-day driving and navigating tasks, augmented by a late, light lunch, which carries us through the afternoon to camp, and another shared routine. Roseann immediately breaks out her journal to record our mileage, location, and the day’s events, then does a sketch or quick field painting of some notable event. Graham, meanwhile, fills in his with much the same notes, but goes on to record numerous details about the vehicle to which he can refer in minute detail later. Want to know what kind of fuel economy we each got between Alice Springs and Birdsville when we crossed the Simpson Desert via the Madigan line? Graham can tell you down to the tenth of a liter.

Meanwhile I will be off snapping photos, which always seems like the lazy approach to recording when contrasted to Roseann and Graham’s diligence. By now, Connie has usually concocted some impossibly ornate tray of canapés with which we can enjoy possibly the best routine of all: sundowners.

I was introduced to the concept of cocktails-at-sundown on my first African safari, when a guide magically concocted iced G&Ts out of a canvas bar in the back of a Land Rover, and we watched a herd of 200 cape buffalo grazing in the last golden light over a plain in Zambia. Since I have tried to watch the sun set every day I can since I was a child, adding alcohol came as a natural why-didn’t-I-think-of-that revelation, and we now adhere to the tradition whenever possible while on the road.

Sundowners would make a good note to end this on, but I have one more routine to which I adhere whenever the sky is clear: Once it is fully dark, I check the sky for celestial sights. I confirm the appearance of favorite constellations depending on season and location: Orion, Scorpius, the Southern Cross and its two pointers. With binoculars I check planets: If Jupiter is visible I can follow the linear dance of its four Galilean moons from night to night; if Saturn is up and on a closer approach to Earth I can make out the rings giving it an apparent oblong shape. (This was the best view Galileo himself ever got with his primitive telescopes, and he went to his grave thinking Saturn was an oblong planet.)

At the end of a day, what could ground one better than the assurance that the universe is still proceeding comfortingly along its majestic course, no matter what continent one is on?

African safari guides and tire pressure . . .

I’m not exactly sure why, but a lot of African and Australian 4x4s still run on split-rim (or, more properly, retaining-rim) wheels and massively belted bias-ply tires with tubes. It might be cost, the supposed (but illusory) ease of servicing in the field, or the brute resistance of those ten-ply tires to the abuse dished out by guides and other drivers who aren’t responsible for actually buying the equipment.

A related archaic practice is the resistance of drivers on those wheels and tires to do anything remotely resembling airing down in difficult conditions. Admittedly you cannot air down a tubed tire to the same degree you can a tubeless tire, for fear of tire squirm ripping the tube’s valve off, but you can certainly vary pressure to more or less suit conditions.

Uh uh, not these drivers.

Graham Jackson and I recently got a hilarious example of this in the Moremi Game Reserve in Botswana. We were parked at a pan watching hippos, crocodiles, and a very nonchalant leopard, when an open Land Cruiser equipped with the standard lodge safari seating module arrived, with two guides and a single guest. The driver came over and asked if I had an air source, as he had a right rear tire that was worryingly low. I pulled our Troopy next to his vehicle and hooked up the ARB Twin compressor, while Graham used our gauge to check the pressure in the suspect tire. He suppressed a smile and showed me the dial, which read a full 45 psi. Dutifully we hooked up the compressor and added ten more pounds. “Okay?” asked Graham, but the guide shook his head and pointed to the barely visible bulge in the tire above the tread. So Graham hooked up the hose again and said, “Say when.” The compressor buzzed, the tire tautened, the guide watched, Graham and I traded glances. Finally the guide nodded and said, “Okay,” apparently satisfied with the appearance of the tire.

Graham quickly checked the pressure again, and handed me the gauge. I snapped a photo before putting it away, with the needle pegged above 75 psi. (At the time we were riding on 24 psi in the rear and 20 in front (in a heavily loaded Troopy), to comfortably negotiate the sandy tracks in Moremi.)

The amazing thing is that the guides get anywhere at all, although Graham has rescued some and Roseann and I have done likewise in East Africa.

Repairing hubs in the field

Recently I was going through archived travel images to illustrate an article for Wheels Afield magazine. While doing so, I noticed a consistent thread running through our photos of Africa and Australia: A significant number of them were of me working on the hubs of various vehicles. There were two sequences of me rigging bodge wire fixes to keep grease caps on the rear hubs of Land Rovers, and one of me (repeatedly) tightening the nuts on the full-floating axle of a 45-Series Land Cruiser. All these, incidentally, involved the use of a multi-tool because the vehicle in question hadn’t been equipped by its supplier with adequate tools.

Then there was our last trip through Australia, during which we found that a mechanic in Adelaide had comprehensively screwed up a simple front hub and bearing service on our Troopy, leaving one loose and one reassembled incorrectly so that it would not engage. (There was also a different color of grease in each hub, leading to guesses that he had actually only “serviced”—i.e. buggered—one.)

It brought home what torture the hubs of an expedition vehicle go through on the rough tracks of the world. The number one cause of backcountry breakdowns is still (according to several sources) tire punctures, the second is battery problems. I’d bet the third is hub and wheel-bearing issues, especially if you include the assembly all the way in to the CV or Birfield.

Therefore I’ve decided that from now on, I’ll make sure our spares kit includes a complete hub servicing kit including bearings and seals. It will take up less space than a hard-cover book but could save a lot of time and grief.

I’ll also make sure I have along the correct special tools needed. In Australia when I disassembled the hubs I was faced with the external snap ring Toyota uses on these hubs.

Graham and I had a decent selection of tools with us, but nothing suited to this fiendish part. Graham finally filed the outside ends of a pair of needle-nose pliers flat, which worked pretty well. How much easier it would have been if I’d had these Knipex pliers made for the job.

Deciding which and how many spare parts is always a conundrum, and will vary with the length, remoteness, and difficulty of the journey. But a complete hub kit is compact and cheap enough to be a permanent fixture along with fuses and belts.

The only three knots you need for paracord lashing

In my opinion nothing beats a ratchet strap for securing cargo. Cheaper cinch straps—even the superior style with the roller buckle—just can’t be cinched tight enough to reliably secure heavier and potentially dangerous items.

But it’s not always possible to use ratchet straps. Often you’ll simply run out of your supply, or the hooks won’t fit where you need to secure a load. Sometimes with a bulky roof-rack load you might need to run your lashing back and forth a dozen times to prevent flapping.

Time for the paracord.

Parachute cord has come a long way since its original application. Now you can find it everywhere from those ubiquitous “survival” bracelets and wrapped “tactical” knife handles to—ready?—the Hubble Space Telescope, where astronauts from the space shuttle Discovery used 35 feet of it to resecure loose thermal blankets protecting the instrument.

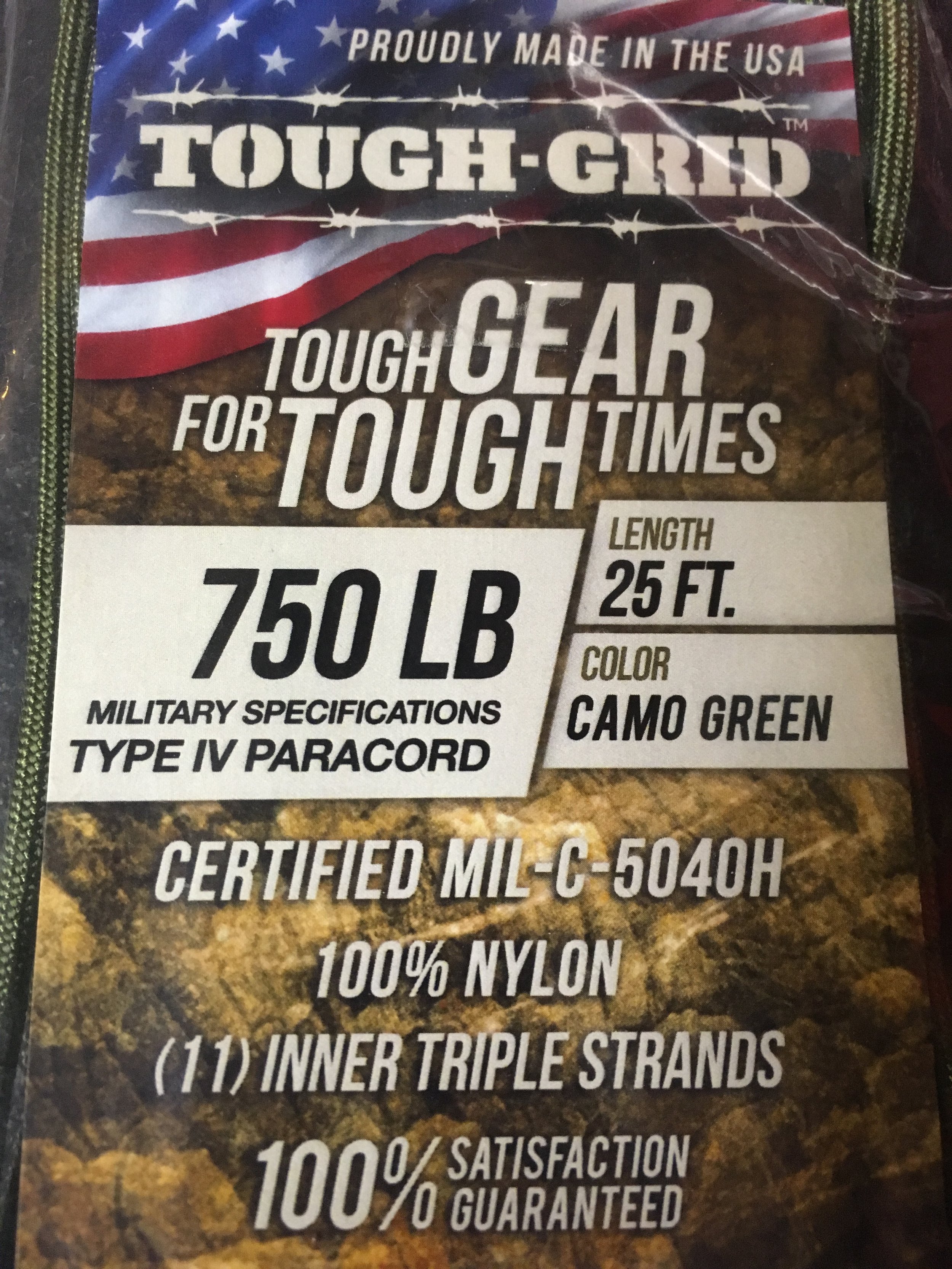

That ubiquity has spawned a lot of substandard variations of the authentic product. Genuine mil-spec nylon paracord will advertise its conformity to military standard C-540H Type III (“550” paracord, indicating its rated breaking strength in pounds), or C-540H Type IV (“750” paracord, again indicating breaking strength). If you pull apart the end of a length of paracord you can confirm authenticity by counting the individual cords within the kernmantle sheath. Genuine mil-spec paracord will have between seven and 11 of them, and each cord will comprise three twisted strands (cheaper paracord might have fewer cords made from only two strands). On genuine mil-spec paracord one of the inner cords will be a contrasting color; this is a marker for the manufacturer.

Even genuine mil-spec paracord is inexpensive enough that keeping a couple hundred feet in the vehicle for odd jobs is affordable. Of course, you can opt for larger and more expensive kernantle cordage, even Kevlar if you want the ultimate in strength. But 550 or 750 paracord is pretty stout, as long as you keep in mind that a knot—any knot, to a greater or lesser degree—will reduce its strength by up to 25 percent.

Once you’ve determined the need for a fabbed up lashing and have cut the length you need, don’t neglect to fuse the end, otherwise the interior cords can protrude and snarl and your work will look decidedly less than pro. I work the kernmantle sheath over the end, so when I apply a flame it (usually) melts nicely and encapsulates the cords. Just make sure you have a solid, tight blob. I find that putting the flame next to but not right on the end helps melt the cord neatly.

Now you need to secure that cargo securely. Paracord has two characteristics that can work with and against you. It’s a bit stretchy, which makes it easier to tell when you’ve pulled it tight enough but can let the load shift if you haven’t. And it’s fairly slippery, which makes it easier to pull tight across duffels and other luggage, but which also means knots can come loose if not chosen correctly and tied properly.

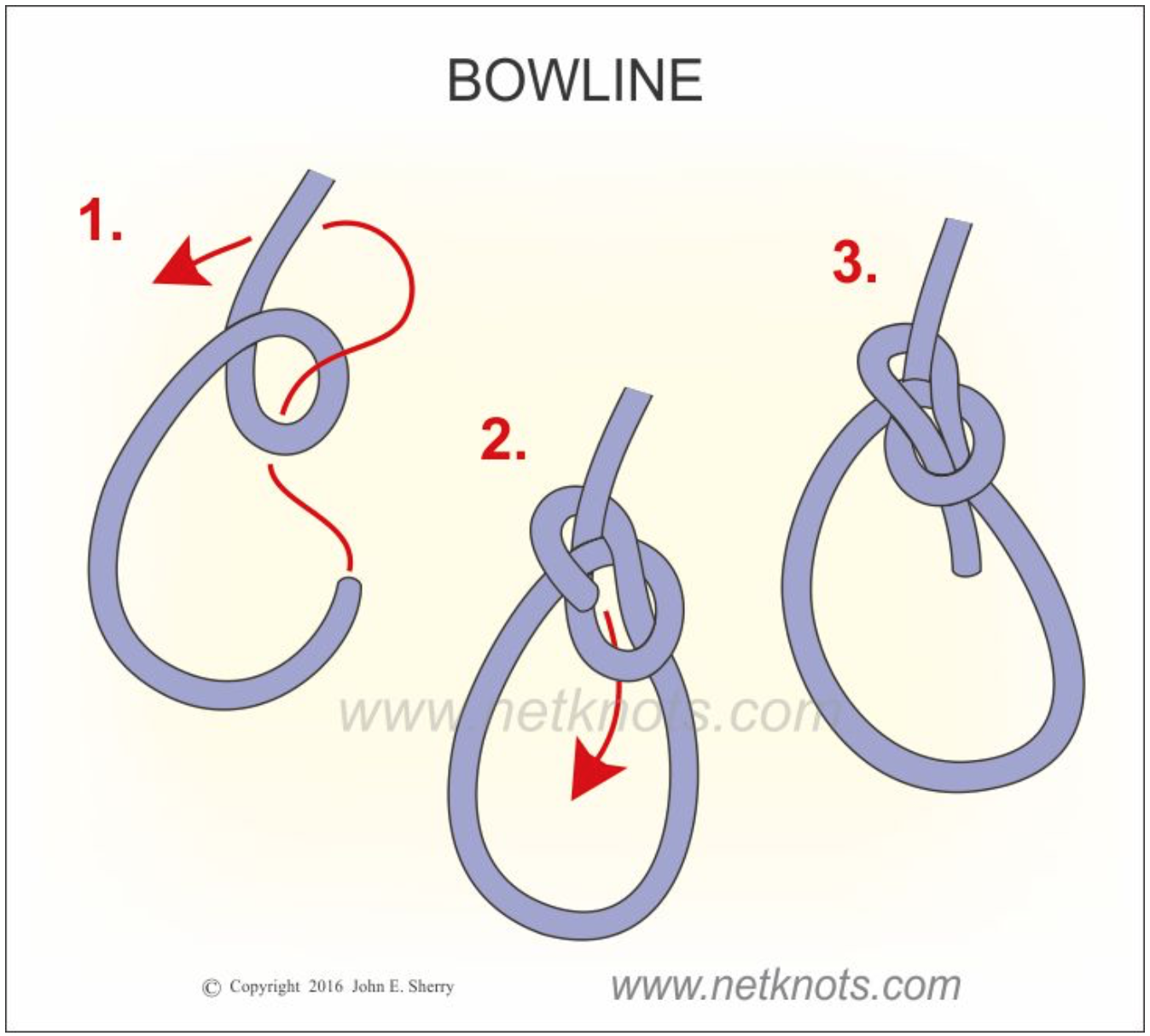

To ensure that, you need know only three: a bowline, a trucker’s hitch, and a sheetbend.

The bowline is the best way to make a secure loop, to tie the first end of your paracord to the roof rack or cargo eyelet. (I’ve blatantly lifted the still images here from the excellent site netknots.com, because I urge you to go there and watch the easy-to-follow animations of these knots, and dozens more.) The bowline is strong, it weakens the rope less than some other knots, yet it is easy to undo.

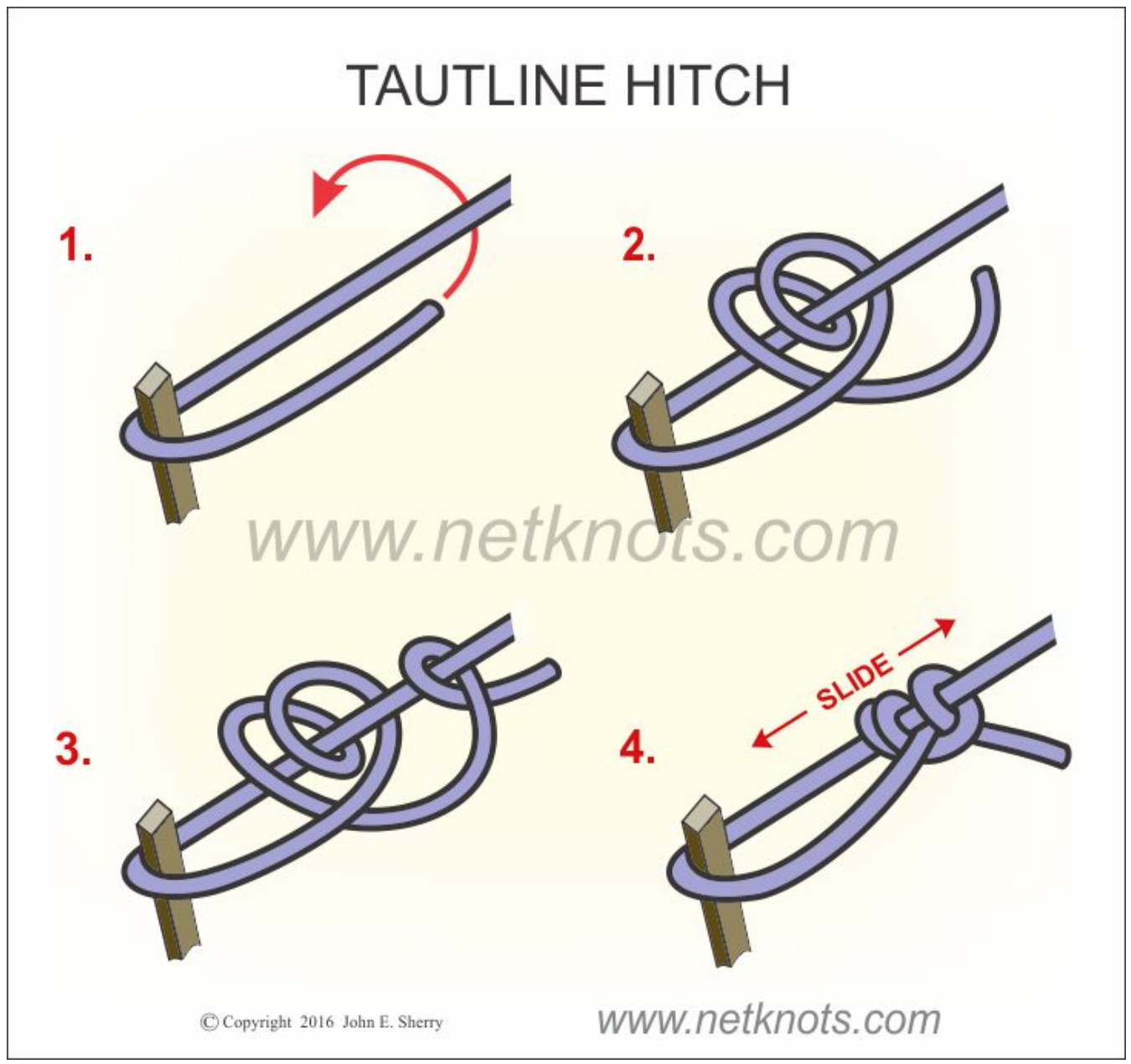

At the other end, you want to pull that cord as tight as possible and secure it so it won’t loosen. The trucker’s hitch actually functions as a jive pulley to multiply the force you’re pulling with, and when tied off properly will not slip.

When using paracord I suggest augmenting the netknots instructions. In part three, they finish off the knot with a single loop (basically a half hitch). However, paracord can slip if secured thusly. I strongly suggest looping the end of the cord through twice, then looping it the opposite direction below, so you in effect add a tautline hitch, like this:

Do this finishing knot right up against the “pulley” loop. Just as with the bowline, the trucker’s hitch unties easily, and in fact the slippery half hitch you tied to use as the “pulley” will pop loose simply by pulling on either end of the cord.

The last knot you’ll use if you need to join two cords that are each too short: the sheet bend. It’s an incredibly simple knot, almost a square knot except the free end of the second (blue here) cord tucks under as shown.

For extra security you can double the knot as in the diagram. The brilliant thing about the sheet bend is that it will effectively join two cords or ropes of different diameter. Just remember to use the smaller line for the second (blue) part of the knot.

And the brilliant thing about all these knots is that they’re useful in hundreds of other situations. So cut yourself a three-foot piece of mil-spec paracord and practice them until they’re second nature. They’ll serve you well.

For want of an M8 x 30mm bolt . . .

It still amazes me how well I can prepare for a long, remote journey, yet still find myself unprepared.

Over the course of four trips to Australia in the Land Cruiser Troopy we bought there, I slowly accumulated a pretty decent selection of tools, highlighted by a superb Bahco S106 combination kit (see here), which includes full 1/4 and 1/2-inch socket sets, wrenches, plus numerous drive fittings. An additional set of 1/2-inch deep sockets, a screwdriver selection, an electrical tester, and various pliers rounds out the kit.

Our recent trip was without doubt the hardest on both our Troopy and that belonging to Graham Jackson and Connie Rodman, as we covered 2,600 kilometers of dirt tracks between Coober Pedy to Perth, some of them heavily corrugated. And as on earlier trips, substandard work done by a mechanic in Sydney (not the Expedition Centre which did all the camper conversions, but a repair shop nearby) began to manifest itself. A new radiator installed on Graham’s vehicle, bought long distance before we arrived—and guaranteed by the mechanic to be “as good as Toyota”—began leaking halfway through the journey. Radiator stop-leak controlled but did not completely plug it. Next, I found the transfer case lever in our vehicle would engage four wheel drive but flopped back and forth rather than engage low range. The nut on that section of linkage had fallen off. (The transmission had been removed to repair a leak before a previous trip.)

A bit farther on, Roseann and I started noticing a rattle that seemed to be coming from the exhaust, as if some gravel had become caught on top of a heat shield. But soon we could hear an obvious exhaust leak. Underneath the vehicle I inspected the “performance” exhaust system the mechanic had installed. A joint near the middle was completely loose. It had been connected with two bolts and nuts—no flat washers, no lock washers, no jam or nylock nut, no Loctite. One bolt and nut was completely gone; the other I easily removed with my fingers, to find most of the thread stripped.

And that was a problem, because while I had plenty of tools with which to install or remove virtually any nut or bolt on the truck, I had not gotten around to the item on my pre-trip list that read BUY SPARE BOLTS AND NUTS.

Sigh . . .

This time I got lucky. We had some leftover washers from a RAM mount, plus several bolts I had bought to secure it, and against all odds they just happened to be a suitable size and length. We were soon back on the road with a quiet exhaust (and Graham had found an extra M8 nut with which to fix the low-range linkage).

Needless to say, when we got to Perth I made my first task a trip to the local Bunnings to get a start on rectifying the situation before we loaded the Land Cruisers into a container for Africa.

One suggestion: I usually buy mostly high-tensile spare bolts (Grade 8 in SAE or 8.8 or 10.9 in metric), figuring that it won't hurt to replace a missing standard bolt with a high-tensile spare, and I can be assured of having the proper strength fastener for a critical component.

New Safe Jack universal base plate . . . and a sale

I’ve written several times before about Safe Jack’s unique products. Read here and here about the expanded base plates they invented for the Hi-Lift jack and bottle jacks, which transform the nature of both kinds of lifting tools.

Previously you had to choose which base you wanted. Now Richard Bogert of Safe Jack has introduced a universal base that accepts either a Hi-Lift base, or a clip-in plate on which almost any standard bottle jack can be clamped. So during a recovery situation in soft substrate, when you need the extra flotation for your Hi-Lift (or the clever and rock-solid guy-wire stabilizing system), you’ve got it, and when you shortly thereafter need to jack up one wheel for a tire repair, you can just snap in a bottle jack to the same base. Nice.

Safe Jack will be at Overland Expo WEST with show specials. If you won’t be there, don’t feel bad: Richard will be running a “Gear up for Overland Expo” web special through May 20th. The website is here, and the promo code is GEARUP2016.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.