Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Irreducible imperfection: The flimsy

At the beginning of the North Africa Campaign in WWII, the British faced a logistics problem on a scale they’d never imagined. In this, the first totally mechanized war, the need for fuel staggered existing supply lines—and existing supply containers. For several decades the British military had made do with a squarish four-gallon soldered-tin can known officially as a POW can—for Petrol, Oil, and Water—to move the bulk of its petrol supplies. The four-gallon size was light enough to be handled by one man (unlike the common 55-gallon drum), and small enough to be transported by light truck or even motorcycle.

But as General Wavell in Cairo mustered his tanks, trucks, and airplanes to counter the forces of the Italians and Germans massing in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (now Libya), the deficiencies of the POW can quickly became all too clear. Stacked in pallets on cargo ships, the weight of the top layers simply crushed those below, resulting in fuel losses of up to 40 percent, and making unloading the intact containers extremely hazardous with thousands of gallons of petrol sloshing around in the bilges and the fumes powerful enough to render seamen unconscious, not to mention the danger of fire or explosion.

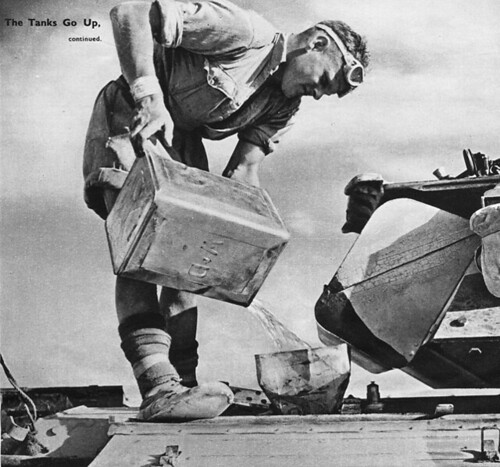

A British soldier refuels a Crusader tank from a flimsy. The funnel appears to have been made from another flimsy.

A British soldier refuels a Crusader tank from a flimsy. The funnel appears to have been made from another flimsy.

Even in smaller shipments the can proved absurdly fragile. Truck transport over 100 miles of desert track frequently left 20 to 30 percent of the contents cascading out the tailgate. In his book The Desert War, Alan Moorehead wrote, “The great bulk of the British Army was forced to stick to the old flimsy four gallon container, the majority were only used once. We could put a couple of petrol cans in the back of a truck, two hours of bumping over desert rocks usually produced a suspicious smell. Sure enough we would find both cans had leaked.”

That adjective, “flimsy,” quickly became a noun, and the POW can became universally known as the flimsy, reviled by troops and brass alike. To get an idea of the numbers used, consider that a single Wellington bomber flying a single nine-hour sortie needed 270 flimsies to fill its tanks. Piles of empty containers 30 feet high stood outside every airbase, and littered the Western Desert wherever British vehicles ranged.

Fortunately, an alternative presented itself when the retreating German Army began abandoning its own 20-liter containers. These were of embarrassingly brilliant design—perimeter-welded of stout steel for strength, with a three-handle configuration that allowed one man to carry two empty cans with one hand (or two full cans if he was strong), and which facilitated effortless hand-off of full cans down a line of men. The leak-proof cap was secured with a fast and foolproof lever, a breather allowed fast pouring, and a clever air trap at the top meant that a full can of petrol would float in water. The British scrounged all the “jerry cans” they could, and in England the design was unashamedly copied to the last detail—two million of them would be sent to North Africa before the end of the campaign. (The U.S. copied the design as well, but substituted cost-saving—and inferior—rolled seams and a screw top that was difficult to seal.)

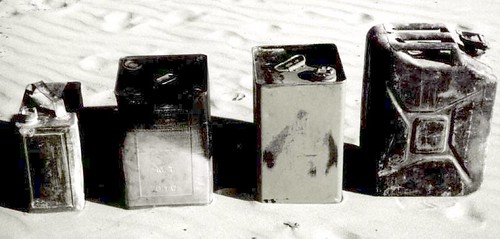

A British two-gallon container, early and later "improved" four-gallon flimsies, and the vastly superior German 20-liter fuel can. Note the thin and awkward handle of the flimsy.In the meantime, the flimsy proved happily more useful as a makeshift device than it did in its primary role. Filled with sand, it became an impromptu building block for gun emplacements and buildings. Cut in half and filled with petrol-soaked sand, it was used as a stove for boiling water (in another half-flimsy), and known as a Benghazi burner or Benghazi boiler (the latter term was subsequently applied to the Thermette, an early volcano kettle supplied to troops from New Zealand).

A British two-gallon container, early and later "improved" four-gallon flimsies, and the vastly superior German 20-liter fuel can. Note the thin and awkward handle of the flimsy.In the meantime, the flimsy proved happily more useful as a makeshift device than it did in its primary role. Filled with sand, it became an impromptu building block for gun emplacements and buildings. Cut in half and filled with petrol-soaked sand, it was used as a stove for boiling water (in another half-flimsy), and known as a Benghazi burner or Benghazi boiler (the latter term was subsequently applied to the Thermette, an early volcano kettle supplied to troops from New Zealand).

The Benghazi burner was also effective for illuminating rough landing strips at night—and that was quite possibly the role played by the crudely bisected Shell example we found in Egypt’s Western Desert this February (top photo). It speaks to the extreme aridity of this eastern edge of the Sahara that after 70 years even something as thin as a flimsy was still in recognizable shape.

Historic bodge fixes: T.E. Lawrence

T.E. Lawrence, on right, enters Damascus in the Blue Mist.

T.E. Lawrence, on right, enters Damascus in the Blue Mist.

Here’s a bit of history David Lean left out of his epic film Lawrence of Arabia: In addition to the camels T.E. Lawrence and his Bedouin allies used on their spectacular raids against Turkish outposts and railroads in what is now Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Syria, Lawrence employed a fleet of automobiles.

An unabashed romantic, Lawrence was nevertheless also an utterly practical (and brilliant) military strategist, despite having no training whatsoever beyond the written accounts of historic campaigns he had devoured since childhood. He was the first battlefield commander to recognize and fully exploit the value of aircraft used in support of ground troops, and he pioneered aerial mapping techniques. His guerrilla tactics are still studied today by insurgents as well as counterinsurgents, yet at Tafileh in January of 1918 he proved himself equally capable of commanding a pitched conventional battle.

Lawrence also quickly realized that on the wide, flat deserts he had to cross with heavy loads of explosives and weapons, an automobile could cover ground much faster than a camel. After his stunning victory at Aqaba, he had the clout to request and receive a small detachment of armored cars, accompanied by automobile “tenders.”

But these weren’t just any automobiles. Lawrence’s desert raiding machines comprised nine Rolls Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost motorcars, including a personal vehicle he named the Blue Mist.

At the beginning of the war, Rolls Royce was already established as a maker of the finest automobiles, catering to the upper crust of society. But in those early days, such a reputation had as much to do with reliability and durability as it did luxury. In 1907 the company had entered one of its 40/50-horsepower models in the grueling Scottish Reliability Trials, and followed up the performance by driving the same car between London and Glasgow—27 times. The Autocar magazine declared it “the best car in the world”—still Rolls Royce’s motto a century later.

A Rolls Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost in more genteel surroundings. (Image courtesy www.ritzsite.nl)

A Rolls Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost in more genteel surroundings. (Image courtesy www.ritzsite.nl)

That tremendous strength served Lawrence well in terrain and conditions far removed from what even Henry Royce had envisioned. In one passage from Seven Pillars of Wisdom Lawrence describes an exploratory excursion: “Their speedometers touched 65 mph; not bad for cars which had been months ploughing the desert with only such running repairs as the drivers had time and tools to give them.”

Alas, even the mighty Rolls Royce proved not completely immune to damage from constant, crushing abuse.

On September 16, 1917, Lawrence and a small team set out to demolish a railway bridge south of Amman, in what is now Jordan. The Blue Mist was “crammed to the gunwale” with explosives and detonators. While his companions, who had followed in another tender, engaged the Turkish post guarding the bridge in a brief but ferocious firefight, Lawrence coolly placed 150 pounds of charges in the bridge’s support spans, ignoring desperate signals from the two British officers supervising the cover fire that Turkish reinforcements were on the way. The explosion sent twisted shards of the bridge plunging into the ravine below, and further enraged the pursuing Turks.

And at that moment, as the group raced away from the rising smoke, one of the Blue Mist’s rear spring brackets snapped, dropping the body onto the tire and instantly halting forward progress. It was, as Lawrence later described it, the first and only time a Rolls let him down in the desert.

Anyone else would have simply abandoned the car, but Lawrence was loath to lose not only his faithful Blue Mist (“A Rolls in the desert was above rubies,” he wrote), but the extensive explosives kit inside. With the Turks perhaps ten minutes away, he and his driver (who was nicknamed “Rolls”) jacked up the car, and untied a length of wood plank kept with each car for deep sand recovery, with the idea of wedging it between the axle and chassis. It was too long, and “Rolls” estimated they’d need three thicknesses of the wood to support the car. They had no saw, but Lawrence solved the problem by simply shooting crosswise with his pistol through the plank several times in two places, until the board broke in three pieces. The Turks heard the firing and paused their pursuit, which lent Lawrence and “Rolls” time to rope the planks in place, using the running board as a mounting point, and make good their escape. Lawrence wrote:

“So enduring was the running board that we did the ordinary work with the car for the next three weeks, and took her so into Damascus at the end. Great was Rolls, and great was Royce! They were worth hundreds of men to us in these deserts.”

So, if you don’t already have them on board your own Rolls Royce, I suggest adding to your recovery kit one (1) wooden plank and one (1) pistol.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.