Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Outdoor Retailer, day 1

Overland Tech and Travel arrived at Outdoor Retailer in sunny Salt Lake City this afternoon. We managed to visit a couple dozen booths before the happy hours began. Over the next three days we will be reporting on new gear as well as just cool stuff. Follow our Flickr Outdoor Retailer set as well (http://www.flickr.com/photos/conserventures/sets/72157630877676310/with/7701752420/).

Here's a preview:

BioLite stove: burns wood (think Kelly kettle on steroids) and generates electricity for charging phones and laptops. Brilliant. A prototype heat-concentrating cooktop, below, was also on display. BioLite.com

Stealth gray KTM 950 Adventure parked in the shade outside the south entrance.

Zippo's beautifully crafted brushed "aluminum" Jeep JK Wrangler, with embossed doors, flame grille, and lighter rear rack box.

Dahon bicycles fold up into small packages, perfect for overlanding around the globe.

Lifeproof's incredibly slender iPhone case is nevertheless shock-resistant (two-meter drop), dustproof, and waterproof to a depth of six feet - which means your phone will now easily survive being dropped in the toilet.

GoPro's display featured this spectacular replica of a legendary Rothmans Paris-Dakar Porsche 911 SC RS.

Do you want it hard or soft? (your motorcycle luggage, that is)

I equipped this test Royal Enfield with a combination of AndyStrapz canvas panniers, a Wolfman duffel, and a Pelican case rack trunk for a traverse of the Grand Canyon's North Rim

I equipped this test Royal Enfield with a combination of AndyStrapz canvas panniers, a Wolfman duffel, and a Pelican case rack trunk for a traverse of the Grand Canyon's North Rim

Just as our instinctive mental image of an expedition vehicle is more than likely a Land Rover 110 or Land Cruiser Troopie equipped with a roof rack loaded down with jerry cans and sand mats, so our image of an adventure motorcycle is likely to involve a giant BMW GS bulging with several square meters of aluminum sheet artfully folded and welded into rugged panniers and trunks covered with flag stickers from far-off places.

Thousands of the owners of these bikes have actually been to those far-off places. But how many riders chose those aluminum cases based solely on Long Way Round videos and magazine articles? How many remained satisfied with the approach after several thousand miles of travel? How many riders switch to soft luggage later on—and by the same token, how many riders start out with soft luggage and later switch to hard cases? Is there an overwhelming argument in favor of either, or is the choice simply a matter of trade-offs and priorities?

The debate has been the subject of endless forum threads begun by curious and innocent new riders. Replies generally fall into one of two categories: 1) “USE THE SEARCH FUNCTION!” or 2) Fifteen pages of opinions backed by rock-solid logic (and sometimes rock-solid experience) but little nuance. It’s either hard-luggage-is-the-only-way-to-go or soft-luggage-is-the-only-way-to-go.

The basic arguments for each are easily summarized. Soft luggage is less expensive, significantly lighter (with the equally important resultant benefit of a lower center of gravity), and not as likely to injure a foot or leg caught between luggage and ground during a spill or when working though rock gardens or sand. Soft luggage rarely requires special brackets to mount, generally results in a narrower bike profile, and can be compressed even further for shorter trips. If a soft pannier clips a rock or other obstacle during slow-speed maneuvering, it’s less likely to catch and throw the bike off balance.

Hard cases provide much better security from both outright theft and slash-and-grab attacks, are sometimes (but not always) more weatherproof, they sometimes can protect both rider and bike in a spill (as long as the situation described above doesn’t happen, and the luggage or its bracketing doesn’t damage the bike’s frame), and if easily removable can serve as seats or tables. Hard cases are easier to pack, provide better protection for fragile equipment, and can be modified easily with brackets for extra fuel canisters, etc.

Doug Mote's hard cases, ready for "easy going."

Doug Mote's hard cases, ready for "easy going."

Summarizing arguments is easy, but it doesn’t make a choice any easier. What I wondered, and had never seen in any luggage threads except as vague hints, was if there might be a formula that would use easily quantifiable variables specific to the rider to point him or her in the right direction.

My own motorcycle luggage expertise (not counting long ago rides wearing a Camp Trails frame pack, which provided spectacular windage) is limited to the excellent canvas luggage from Andy Strapz, combined with an equally excellent Wolfman duffel, and a Pelican case pressed into service as a security trunk. The combination suited me perfectly, but I wanted to get input from those with far more extensive riding history. So I sent out a poll asking the question: hard or soft, and why? I hoped the results might coalesce into a logical hierarchy that would lead to a simple formula.

Those who shared their experience included Carla King, Tiffany Coates, Lois Pryce, Austin Vince, Doug Mote, Kevan Harder, Nicole Espinosa, Brian DeArmon, and Bruce Douglas. The result comprised what I considered to be a useful cross-section of the long-distance riding community—both sexes, and a mix of body sizes, travel styles, and motorcycle choices (from 250 to 1200 cc).

Indeed, as I began going through the responses from this vast pool of experience, definite trends became apparent. In the end I was able to come up with an algorithm accurate enough that I could plug in variables from almost any of the experienced riders I polled and correctly predict what kind of luggage he or she used in what situation.

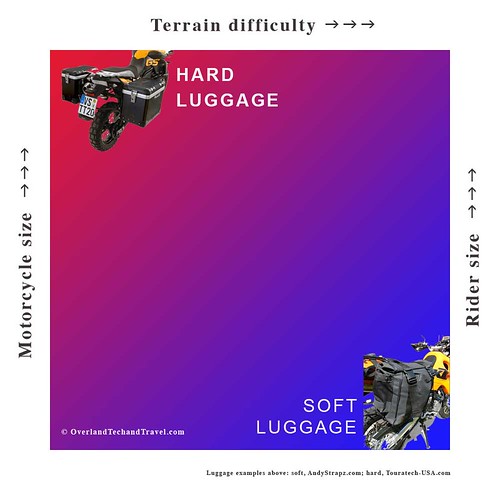

Essentially (aside from your budget), I decided only three variables are necessary to determine which type of luggage will best suit you. While there is some gray area, in general I think most people will find themselves trending one way or the other. The variables are:

- Size of motorcycle

- Size of rider

- Difficulty of terrain

No earth-shaking revelations there, but the relationship between the three can shift things one way or another. The chart shows how the recommended choice shifts from hard (red) to soft (blue), with purple as the could-go-either-way middle ground.

Simply explained, if you’re a big rider on a big bike and stick to asphalt or fairly well-maintained dirt roads, the advantages of hard luggage will most likely outweigh its disadvantages. Conversely, a small rider on a small bike who frequently challenges technically difficult routes would almost certainly be better off with soft luggage.

Some ambiguity arises if we start mixing and matching variables, but the observations of our experts still tilt the smart choice one way or the other. For example, small bikes—say under 650 cc—have a harder time coping with the weight and windage of hard luggage, regardless of terrain. Similarly, a big rider on a big bike who finds himself in central Africa during the rains, or deep in Egypt’s sand seas, or even on three-plus-rated 4x4 trails in the American West, will still benefit from the lighter weight, lower CG, and forgiving impact absorption of soft luggage.

As filmmaker Sterling Noren recently found out, even anodized aluminum cases aren't impregnable

As filmmaker Sterling Noren recently found out, even anodized aluminum cases aren't impregnable

There’s also one more option to be considered regarding hard cases: While the Ewan-endorsed, steamer-trunk-sized aluminum cases represent the paradigm of hard luggage, lighter and smaller plastic cases, such as those offered by BMW for the F 650 GS, represent a viable middle ground in price, weight, and windage (and security). Another increasingly popular approach is to mount a small hard case such as a Pelican as a rack trunk, to provide security for cameras, laptops, and such, and go with soft cases for the rest of the luggage.

Here are some of the comments from our panel of experts, who collectively total a couple of million miles of motorcycle travel, including four circumnavigations.

Carla King’s motorcycle adventures began in 1995 with a 10,000-mile circumnavigation of the U.S. on a Ural with a sidecar, and haven’t stopped since. You can order the delightful book documenting the trip, along with her other published works, from her website here. Carla wrote, “Right now I’m setting up a new-to-me KLR, for which farkle options are famously infinite. After much research into cost, durability, security, convenience, and safety, I chose the Giant Loop soft luggage. Seems I can throw it on any bike, stuff almost any size and shape of thing into it, check it as luggage, and perhaps most importantly it’s not going to crunch my bones when I ride beyond my skill level and fall on (insert hard object here).”

Tiffany Coates set off on her first motorcycle trip, from the U.K. to India, with two months of riding experience. She has a bit more now—over 200,000 miles worth and counting, including the riding she did while filming a BMW unscripted commercial on Thelma, her much loved and well-used BMW R80GS. Tiffany still nurses the factory plastic cases that came on the bike, the latches of one of which long ago gave up trying to hold in the contents (small wonder - see photo below). According to her, “For me, the BMW plastic cases are ideal. Perfect size, with the ‘suitcase compression’ system which means I cram everything in and then sit on it (or two of us if we’re two up). Apparently we get more in these cases than the large metal ones due to the compression. Cheaper and lighter than metal cases and smaller—no risk of getting a leg caught under them if there is a fall. Also ultra-easy to unlock and whisk off the rack ready to carry into a hostel, or for emergency unloading in a river fall! As they are hard cases they are secure as well. I’m not anti-soft luggage, I have just never used it as the BMW panniers were on Thelma when I got her and so I never had a decision to make about what luggage to use.” Find out where Tiffany is now here.

Tiffany and a friend do a little cargo compacting

Tiffany and a friend do a little cargo compacting

Lois Pryce couldn’t seem to exorcise the motorcycle travel bug by riding a 225 cc Suzuki from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. So she traded up to a much bigger bike (250 cc) and rode from her home in England to Cape Town (two excellent books here). As she was on tour in the Netherlands with her bluegrass band, the Jolenes, when I emailed her, her reply was short but thorough: “I prefer soft luggage: lighter, less ostentatious, no need for a rack, easy to lift on and off, easy to repair, and cheaper to buy. AndyStrapz panniers are the best.” (Want to hear the Jolenes? Go here. Lois is the banjo player.)

Austin Vince’s main claim to fame is that he’s married to Lois Pryce. Oh, well . . . he’s also ridden a Suzuki DR350 around the world. Twice. And made a rousing film of each trip. Austin is the antidote to anyone who tells you you need a $20,000 motorcycle and a further $5,000 in kit to do any serious adventuring. His riding suit is a pair of mechanics’ coveralls. His goggles appear to be Audrey Hepburn’s castoff sunglasses from Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Tent? A surplus shelter half. Luggage? I’ll let Austin explain.

“Soft. Here’s why:

1) Looks cooler and less aggressive compared with armoured-car-ish aluminum boxes. I really do think this is important when travelling amongst poorer societies.

2) Easily personalized and created from government surplus stores, etc. If your luggage is improvised then you are richer in terms of investment in your project. My current ALICE pack system has two major bags of 40 litres each, and 12 separate mini pouchlets of varying smaller volumes, all super-useful: Oil, rags, toilet paper, sun cream, water, etc. is all instantly accessible without undoing a single flap. Total cost, $35 U.S. No manufacturer can match this.

3) Safety. No one has broken a leg on a soft pannier.

4) Luggage is easily repaired and conversely, if it gets damaged, it only cost $35 so who cares?

5) All my DIY luggage is zero waterproof so I simply put my gear in a $5 waterproof liner therein—it’s so simple I want to cry.

6) Hard luggage makes the bike physically massive and far too unwieldy.

7) Jonathan, I love you (call me—like the old times).”

(Editor’s note: I take no responsibility for number 7. Just passing it on in the interest of full disclosure.)

Austin Vince's $35 pannier system (courtesy U.S. government surplus)

Austin Vince's $35 pannier system (courtesy U.S. government surplus)

Brian DeArmon is the thinking rider’s rider. Every equipment choice he makes is the result of not just long experience as a motorcyclist, but extensive research into pros and cons, competing brands, and above all, quality. Generally when Brian adds something to one of his bikes, that’s the last you hear about it, because it works. Given all that, it was no surprise that his detailed response more or less summarized my conclusions before I even reached any.

“Short version: Bigger bikes that are being used on easy to moderate terrain, with predictable weather conditions, I tend to favor hard bags (primarily for the security and ease of access). For small bikes, or any bike going where trail conditions are unknown, I prefer soft bags.

Long version:

Suspension: It’s too easy to overload a small bike already. Add in 15 or 20 pounds for the hard panniers and mounting brackets, you eat into valuable capacity. The big bikes are better able to handle those loads. Unfortunately, hard panniers also make it real easy to strap even more crap on the bike since they typically create a nice big surface area & include those nice tie down points.

Power: Smaller bikes typically don't have the power to push big loads down the road at the speeds required in the west. I've ridden the DR200 on the freeway with no load, and it’s kinda scary, even in the slow lane. I couldn't imagine doing it with an extra 40 pounds of pannier/gear/food/water (state highways and back roads, sure, just not freeways where traffic is moving 70 to 80 mph). Put that load on a GSA or big KTM and you don't have the same problem.

Trail conditions: On relatively tame roads, in known weather conditions, hard panniers are not much of a liability, IMO. The risk of crashing isn't that high. But once conditions become unknown, or weather conditions make a turn towards the wet side (mud), hard panniers become a huge liability. There is the obvious danger of tib/fib breaks, but also damage to the bike itself. My GS has a bent subframe caused by smacking a pannier on a rock. That is hardly a concern with soft bags.

Security and Convenience: Hard bags have a hands-down advantage for security and ease of use. Dump in your gear, close the lid, lock the latch, and you’re done. They’re typically easy to dismount and move into a hotel room, etc. Soft bags often have a convoluted mess of straps that makes it more difficult to access gear and install or remove. Soft bags also need to be checked regularly as loads change and straps loosen. Of course there is also the problem of having nothing between your gear and a thief but a knife.

Basically, I see soft bags as the default luggage system, with hard bags being a legitimate option if certain conditions are met.”

Nicole Espinosa didn’t like the racks available for the Suzukis she rides, so she made her own. Now she runs a business, Rugged Rider, which specializes in high-quality accessories for the reliable and overachieving small DRZs. Nicole wrote: “I feel the DRZ400 is the perfect bike to set up for adventure. It has a strong enough engine to maintain a comfortable 70 MPH on the highway, and is a nimble enough size to have fun on tight single-track fully loaded. That said, I prefer soft luggage for a tighter profile on highway against wind, and on trails for width. I only keep my clothes and rain gear in my Ortleib dry side bags, and have only traveled in North America as of yet, so I haven’t put the security of soft bags to the test internationally. I keep my expensive gear in my tank bag that I can carry with me or ratchet down on my locking combo luggage rack.”

All you need to know about Doug Mote as a rider is summed up below in his reference to “easy going.” Anything else I’d add would be superfluous, except to say he’s one of the nicest guys I know (despite his comment about kicking KTM ass). As a lumberjack and body double for Paul Bunyan, Doug was at the far end of my bell curve for big riders with big bikes. He sent: “I have hard and soft luggage, and use both. My preference depends on itinerary. For easy going, like say a run to Prudhoe Bay on a schedule, hard bags offer several advantages, not the least of which is better weather protection. On this type of good road trip in wide open spaces, there is little risk of leg or foot injury such as I have witnessed friends incurring when trapped between bag and earth. For tough going, where lightness and flexibility are key, soft luggage is superior. Spills are not so risky, and my entire kit weighs less than empty hard bags with mounting racks. I use only soft bags on the 650, either soft or hard with the 1150 depending on the route and how much KTM ass there is to kick. For extended travel with diverse route conditions, soft luggage is my clear choice."

I won’t claim that Bruce Douglas sometimes uncovers a motorcycle in his yard he’s forgotten he owns, but he does own a lot of them, and has based his transportation on motorcycles since his very first vehicle, a two-stroke Yamaha 360. His main backroad bike is a thoughtfully modified Suzuki DR650. Bruce wrote: “I’d say hard cases for security, appearance, and good mounting surface for other stuff. I think they’d be fine if I knew I wouldn’t be riding through any difficult terrain, but if there was a chance I might go down I’d have to go with soft bags. A few times when I’ve put my foot down while moving on the TransAlp I had it get caught under the hard case. It was clear how easily you could break something—and it wouldn’t be the case. I think I’m sold on soft bags now after the Baja trip. I like their versatility; I can use different bags with my mounts, since the main function of most mounts is to keep the bags away from the rear wheel. I’m happy with what I have, they’re simple and straight forward. The Wolfman Gen 2 mounts are interesting: a little complicated but they add more mounting points, and a means to carry extra fuel. Also knowing I can repair them with a sail needle and thread is nice. In a spill they flex, rather than dent. If the mounting straps tear off you can come up with a repair, or just tie it on with cord. The chance of the mounts coming out of hard cases is slim, but if they did, a field repair would be difficult. Soft bags aren’t as secure, but after undoing a few straps you can pull them off as saddle bags and carry them over your shoulder (a la John Wayne). In Baja I was able to carry all my gear in one trip: saddle bags on my shoulder, the tail bag in one hand, and whatever in the other hand. Soft bags also make you think about packing and not be tempted to just dump stuff into metal boxes.”

And finally, from Kevan Harder, a California police and SWAT officer who also works for RawHyde Adventures, where it often seems motorcycles are defined as BMW or . . . everything else . . . comes a firm vote for the red corner of the chart: “I strongly recommend hard bags for durability, protection of gear, and versatility (bike service stand, chair, table, etc).”

So there you have it, courtesy of some of the most experienced riders on the planet: an easy way to determine what type of motorcycle luggage will best suit you, your bike, and your riding.

Think this will end all those forum debates?

Irreducible perfection: The Klean Kanteen insulated bottle

My first canteen was a canteen—a WWII surplus aluminum one-quart M1910 with a chained bakelite cap sealed with a cork gasket. I was seven years old, my family had just moved out to the edge of the desert, and I thought that canteen was the coolest thing on earth (well, except for the sheath knife my stepfather had given me in a bizarre fit of generosity). The canteen and several similar examples served well for countless desert hikes and early backpacking trips into the Catalina Mountains, until replaced with stylish and lighter Olicamp polyethylene bottles, which in their turn were replaced with Nalgene bottles—my resulting antipathy to which is well documented (see here).

In the early 2000s, my search for a better bottle led me to try one of the new stainless-steel Klean Kanteens, despite the fact that that I found the brand name wincingly Kute. The KK, as we’ll call it, seemed to be a vast improvement over the degradation-prone Nalgene. But the “Klean” part of the name was soon called into question when I found that the rolled lip of the bottle, while comfortable to drink from, had a miniscule gap underneath, which after prolonged use resulted in a funky odor that was difficult to exorcise—annoying in a $20 water container. That led to yet more searching, which resulted in an obsession with the even more expensive but indestructible Osprey NATO canteen (more about this in a future article).

However, for some time Roseann has been urging me to try one of Klean Kanteen’s double-walled, vacuum-insulated bottles. A different lip design eliminates the bacteria trap of the original, and the benefit of insulation seems obvious in a desert (although privately I thought the vacuum space pretty thin to be of much value). So, one recent morning when I needed to spend the day in town in the un-air-conditioned FJ40 with a trailer, collecting building materials, and the predicted high was 105º, I filled a 20-ounce insulated KK bottle with water from the fridge and headed in.

Six hours later I hadn’t touched the bottle. All my stops had been places with water fountains, so I’d stayed hydrated. Now, heading west toward home on Highway 86, I was thirsty. The bottle had been in the center console all day, and was now sitting in full sun. The exterior was uncomfortably hot to hold. Okay, now we’ll see, I thought. I opened the lid and took a sip.

The water was . . . cold. Not just nice and cool, but decidedly cold. It was awesome, and I drained most of it in one go.

Suddenly I found myself examining the bottle with new eyes (after I got home, that is). The “Responsibly made in China” label on the bottom made me roll my eyes; however, after reading up on the (still family-owned) company’s site, it does appear they take more care than most to ensure good working conditions in the factory (KK also belongs to the 1% For The Planet project).

There’s certainly no issue with quality: The bottle is made from 18/8 stainless steel, thick enough that it takes most of my thumb strength to even slightly deflect it. The brushed finish is as even inside as out, and the cap, while obviously not vacuum insulated, does have an air space to help keep contents cold or hot. Sure, I’d be happy if it held more—the 20-ounce size is the largest of KK’s double-walled bottles—but if the bottle were fatter it would be difficult to hold with one hand, and if it were taller it would be unwieldy and unstable. Besides, 20 ounces of cold water feels way more refreshing than a liter of 105º water from my NATO canteen. Titanium option? Well, okay, but titanium, while saving a few ounces, would add hugely to cost, so that’s a tradeoff rather than a failing. I note that the company makes a bicycle cage for the double-walled bottle, which could easily be adapted to suit a motorcycle—nice to have all-day cold water available on a warm ride.

Not as cool as a NATO canteen - but much colder

Not as cool as a NATO canteen - but much colder

Every once in a while I come across a product that defies my best attempts at criticism—when function, style, durability, price, and social responsibility (40 million water bottles go into the trash in the U.S. every day) come together to create what I refer to as irreducible perfection. I have to add the KK double-walled bottle to that short list.

As long as I don’t have to write out the name. Hey, if they made a Kup I could call it the . . . never mind.

Ditch the cigarette lighter

On the left, cigarette-lighter outlet: plastic body and lock ring, guaranteed-to-break rubber cover "hinge," press-fit back plate. On the right, German-made DIN receptacle: metal body, brass lock ring, rigid cover with spring-loaded hinge. The cordless automotive cigarette lighter was patented 90 years ago, and assumed its present configuration in 1956. I know for a fact that by 1960, car campers already had a range of 12-volt appliances from which to choose, such as the Boilmaster Junior Compact Kitchen coffee percolator featured in my old copy of The Ford Treasury of Station Wagon Living.

On the left, cigarette-lighter outlet: plastic body and lock ring, guaranteed-to-break rubber cover "hinge," press-fit back plate. On the right, German-made DIN receptacle: metal body, brass lock ring, rigid cover with spring-loaded hinge. The cordless automotive cigarette lighter was patented 90 years ago, and assumed its present configuration in 1956. I know for a fact that by 1960, car campers already had a range of 12-volt appliances from which to choose, such as the Boilmaster Junior Compact Kitchen coffee percolator featured in my old copy of The Ford Treasury of Station Wagon Living.

That means that for five decades those wishing to use their vehicles’ cigarette lighters for anything besides igniting a Pall Mall have put up with the “UL Standard 2089” 12-volt plug to try to get DC power to their portable percolators, tire pumps, GPS units, inverters—even their National Luna 74-liter double-door fridge-freezers.

Are we really that submissive to the dominant paradigm? If GM reintroduced front drum brakes and two-speed automatic transmissions would we all go, “Well . . . okay!” We’re talking the same era here.

Anyone who has ever used a standard auto lighter receptacle as a power outlet knows they’re garbage for that application. It’s impossible to tell when the positive post in the center of the male plug makes contact with the positive tab at the back of the female unit, and—especially if your appliance’s plug doesn’t have a spring-loaded post, or if the spring has seized, as most do after about two months of use—contact can be lost with no warning except when you stop for a cold Coke three hours later and find only tepid Cokes in the fridge. Worse, the most common aftermarket cigarette-lighter-type “power outlets,” which many of us install to run extra equipment, are constructed with a plastic back plate for the positive contact that is a simple press fit into the plastic body. Push too hard on the plug and the whole back end of the receptacle pops off.

There’s a better way, and by this time European readers and a lot of American BMW GS riders will be nodding their heads knowingly. They’ve been happily using the DIN (Deutsches Insitut für Normung) 12-volt plug system for years. The DIN plug, while more compact than the cigarette lighter (11/16-inch mounting hole versus one and a quarter) is significantly more rigid and wobble-free. The dash (female) socket grips the positive post of the plug with spring-loaded fingers—push in the plug and it snaps home with an authoritative click. No risk of pushing too hard, no risk of accidental disconnection, even on the roughest roads.

After years of muttering and cursing, and a brief consulation with my friend Brian DeArmon, I finally made the switch, courtesy of our local BMW motorcycle dealer in Tucson, Iron Horse. It’s easy to do, although if you want to install a DIN outlet in a hole made for a cigarette lighter you’ll need to buy or fab a thin washer to reduce its diameter. On the dash of my FJ40 I decided to leave the old receptacle in place so I wouldn’t have to use an adapter when borrowing or testing appliances equipped with that plug. I had a perfect place just below the old receptacle to install a DIN unit, where my stock dome-light switch was located. Since I use a Hella map light for a dome light now I had no need for the switch, so I simply enlarged the hole and installed the DIN receptacle. For now I just siamesed the wires to both receptacles and use a single fuse, since I never run two heavy-draw appliances from the dash at the same time.

FJ40 dash with cigarette-lighter outlet, stock dome light switch underneath.

FJ40 dash with cigarette-lighter outlet, stock dome light switch underneath. DIN receptacle in place, wired in parallel.

DIN receptacle in place, wired in parallel.

If you don’t have a BMW dealer nearby, you can get DIN plugs and accessories from a company called Powerlet. The standard socket is part #PSO-001, and there is a selection of plugs, including a nifty low-profile right-angle version. They even have a pretty decent-looking cigarette-lighter plug if you’re a fan of two-speed transmissions, or would like to leave one standard socket in the vehicle as I did.

Swapping plugs on your old appliances is easy, too. Some 12V fridges come with convertible plugs; a red spacer allows use with a cigarette lighter; remove the spacer for a DIN receptacle. It works okay, but switching to a DIN-only plug is more compact and stronger.

Straight and right-angle DIN plugs are available.As with many such simple and effective modifications, my only regret has been, why did I wait so long?

Straight and right-angle DIN plugs are available.As with many such simple and effective modifications, my only regret has been, why did I wait so long?

10 Great Last-minute Christmas Suggestions

Whether your preferred mode is motorcycle, truck, bicycle, or foot, Overland Tech & Travel editor Jonathan Hanson offers up great last-minute gift suggestions for the overlanders on your list—or a treat for yourself.

Fenix E11 LED microlight ($27)

Fenix E11 LED microlight ($27)

I remember when I thought a halogen flashlight that produced 70 lumens from two expensive lithium batteries (for one hour) was hot stuff. The E11 puts out 105 lumens for almost two hours from a single AA battery—or a walking/reading-level 32 lumens for eight hours on low. Astonishing. Headed to the developing world? Take several—they make genuinely useful trade items or gifts. Fenix

Whether your preferred mode is motorcycle, truck, bicycle, or foot, Overland Tech & Travel editor Jonathan Hanson offers up great last-minute gift suggestions for the overlanders on your list—or a treat for yourself.

Fenix E11 LED microlight ($27)

Fenix E11 LED microlight ($27)

I remember when I thought a halogen flashlight that produced 70 lumens from two expensive lithium batteries (for one hour) was hot stuff. The E11 puts out 105 lumens for almost two hours from a single AA battery—or a walking/reading-level 32 lumens for eight hours on low. Astonishing. Headed to the developing world? Take several—they make genuinely useful trade items or gifts. Fenix

Hasyun merino wool underwear (from $43)

Hasyun merino wool underwear (from $43)

I just tried out this very affordable base layer system in 5º Fahrenheit blizzard conditions on a strenuous elk hunt. Verdict: Scrumptious. Wait, I didn’t mean to write that. What I meant was, “Excellent.” Hasyun underwear—made in Turkey since 1952—uses Woolmark accredited extra-fine merino wool from New Zealand. It’s sensuously soft and warm for its weight, machine-washable, and won’t retain odors like that nasty polyester stuff. The small/medium size in both top and bottom fit my 150-pound, 5’9” frame perfectly. Available in both men’s and women’s, imported by a little company that also sells, um, kid’s bicycles. Go figure. Hasyun

MSR Titan titanium pot ($60)

MSR Titan titanium pot ($60)

Pot, kettle, bowl, mug, scoop—MSR’s brilliant 4.2-ounce Titan pot does it all. It’s the only cook kit you need for a solo motorcycle tour, or a compact coffee-making system for your 4x4. An MSR Pocket Rocket stove and fuel canister ride neatly inside. I’d like to have one of these stashed in every vehicle we own. It should be the official MoMA ultralight cooking pot. Simply perfect.MSR Titan

Vintage pocket compass ($60-$140)

Vintage pocket compass ($60-$140)

You can employ a vintage pocket compass two ways. Produce it with a flourish from a vest pocket, leashed on a leather cord or—better—a silver chain, and flip open the lid to consult it as Selous might have on his way to the Rufiji River. Or, glance at it surreptitiously, then point to the horizon and say sagely, “That should be north.” Either way your companions will be impressed. I carry my WWII-era Wittnauer version everywhere—it’s especially handy for remaining oriented south of the Equator, where the sun always seems to be in the wrong place. This young woman (Kornelia Takacs, who also wrote the book Compass Chronicles), has a wonderful selection: Vintage compasses

Helle Temagami ($170)

Helle Temagami ($170)

Everyone should own at least one really good sheath knife—and if it happens to be beautiful as well, all the better. The Temagami (say teh-mah-gah-mee) from Norway is both. A hand-filling, oiled curly birch handle surrounds a superb laminated steel blade—two resilient 18-8 stainless outer layers sandwiching a high-carbon cutting edge. Like all Helle knives, the Temagami comes razor sharp, in a leather sheath that works equally well for right- or left-handers. I’ve included two suppliers: Feathered Friends, who also make some of the best down sleeping bags in the world, and the delightful Ragweed Forge, which you should visit anyway. Feathered Friends Ragweed Forge

Overland Expo 2012 Gift Certificate ($265)

Overland Expo 2012 Gift Certificate ($265)

Okay, it’s our own event, but after all, think of what you get: Three days of classes & programs (over 80 to choose from); driving instruction from Camel Trophy team members in your own vehicle or a new Land Rover; an all-new Camel Trophy Overland Skills Area where you might, say, learn how to build a bridge to get your 110 across a washed-out ravine; motorcycle instruction from RawHyde Adventures, the official BMW training partner; over 120 vendors & exhibitors of high-quality overlanding products & services; the Adventure Travel Film Festival; happy hours; and a barbecue to wrap it all up. We’ll do up a custom e-Card or printed card. Find out why people come again and again. Overland Expo

Cerberus (from $499)

Cerberus (from $499)

The era of one-way “I’m okay” or “Help!” global messaging is over. The Cerberus device twins with your smartphone to allow two-way text messaging from anywhere on earth. If a cell network is not available, Cerberus automatically switches to the Iridium satellite network. You can send up to 160-character messages, and receive up to 1600-character messages. In an emergency it allows detailed two-way communication with a 24/7 command center. You can also drop breadcrumbs, and receive customized regional weather and geo-political alerts. We’ll be testing a unit in the Egyptian desert early next year, so that last feature might come in handy. Cerberus

ARB CKMTA12 air compressor ($540)

ARB CKMTA12 air compressor ($540)

For years, owners of vehicles equipped with ARB’s legendary diff locks have been abusing the tiny little compressors usually supplied to activate them, by adding a connector for filling tires. Surprisingly, they seem to hold up to this quite well, but the process is glacial and the compressors can reach glow-in-the-dark temperatures. The company’s new twin-cylinder compressor will still activate lockers, but its tire-filling and air-tool-operating capacity is in a different universe. It’s fully up to the job of serving as a hard-mounted vehicle-wide air-supply system, with a stout 100-percent duty cycle. (But, really, couldn’t they have just called it the ARB Twin-cylinder Compressor?) ARB

Goal Zero Sherpa 120 Adventure Kit ($670)

Goal Zero Sherpa 120 Adventure Kit ($670)

Never run out of power again for your laptop, tablet, or phone, with Goal Zero’s 120-watt-hour power pack (AKA lithium iron phosphate battery) and 27-watt folding solar panel—small enough to pack into your panniers. You can also charge the power pack from a wall outlet or cigarette lighter. What impresses me most about Goal Zero is the foolproof plug-and-play nature of their systems, any of which can be effortlessly augmented with additional panels and batteries (or a 120-volt AC inverter). Goal Zero

La Peregrina Natural Pearl Necklace ($3,000,000)

Just seeing if Jonathan is paying attention. (Elizabeth Taylor’s jewelry collection is up for auction at Christie’s; a nice little trinket, this, though not suitable for overlanding in all countries). Christie’s

Fit to be tied: Tie-down torture tests the metal of Expeditionware Transport Loops

I’m never sure which alarms me more: a vehicle loaded with completely unsecured cargo and equipment, or one loaded with cargo and equipment secured poorly. After all, the former implies simple ignorance on the part of the owner, and ignorance can be overcome with education. But the latter implies some rudimentary level of awareness—and then a complete failure to do the simple arithmetic that will tell you what will happen to the 30-pound Hi-Lift jack bungeed to your front brush guard should you be, say, rear-ended at a stoplight. No, I am not making this up, and yes, I checked. Two neatly wound bungee cords comprised the total attachment of that jack to that brush guard. I’ve seen another Hi-Lift bungeed to a very well-constructed internal roll cage (talk about Manichaean reasoning), and uncounted tool boxes, fridges, and Pelican cases all held down by what are, let’s be frank, glorified rubber bands.

I’m never sure which alarms me more: a vehicle loaded with completely unsecured cargo and equipment, or one loaded with cargo and equipment secured poorly. After all, the former implies simple ignorance on the part of the owner, and ignorance can be overcome with education. But the latter implies some rudimentary level of awareness—and then a complete failure to do the simple arithmetic that will tell you what will happen to the 30-pound Hi-Lift jack bungeed to your front brush guard should you be, say, rear-ended at a stoplight. No, I am not making this up, and yes, I checked. Two neatly wound bungee cords comprised the total attachment of that jack to that brush guard. I’ve seen another Hi-Lift bungeed to a very well-constructed internal roll cage (talk about Manichaean reasoning), and uncounted tool boxes, fridges, and Pelican cases all held down by what are, let’s be frank, glorified rubber bands.

I’m never sure which alarms me more: a vehicle loaded with completely unsecured cargo and equipment, or one loaded with cargo and equipment secured poorly. After all, the former implies simple ignorance on the part of the owner, and ignorance can be overcome with education. But the latter implies some rudimentary level of awareness—and then a complete failure to do the simple arithmetic that will tell you what will happen to the 30-pound Hi-Lift jack bungeed to your front brush guard should you be, say, rear-ended at a stoplight. No, I am not making this up, and yes, I checked. Two neatly wound bungee cords comprised the total attachment of that jack to that brush guard. I’ve seen another Hi-Lift bungeed to a very well-constructed internal roll cage (talk about Manichaean reasoning), and uncounted tool boxes, fridges, and Pelican cases all held down by what are, let’s be frank, glorified rubber bands.

I’m never sure which alarms me more: a vehicle loaded with completely unsecured cargo and equipment, or one loaded with cargo and equipment secured poorly. After all, the former implies simple ignorance on the part of the owner, and ignorance can be overcome with education. But the latter implies some rudimentary level of awareness—and then a complete failure to do the simple arithmetic that will tell you what will happen to the 30-pound Hi-Lift jack bungeed to your front brush guard should you be, say, rear-ended at a stoplight. No, I am not making this up, and yes, I checked. Two neatly wound bungee cords comprised the total attachment of that jack to that brush guard. I’ve seen another Hi-Lift bungeed to a very well-constructed internal roll cage (talk about Manichaean reasoning), and uncounted tool boxes, fridges, and Pelican cases all held down by what are, let’s be frank, glorified rubber bands.

Bungees have their uses, but heavy cargo in an overland vehicle should be secured with ratchet straps capable of withstanding the forces generated should you experience an unplanned encounter with Isaac Newton. Anything much heavier than a sleeping bag can cause injury or worse in an accident or rollover. (Come to think of it, I wouldn’t want to be clobbered by my 18-pound Butler sleeping bag . . .)

Decent ratchet straps are available at any hardware store. But very few, if any, vehicles come from the factory with tie-down points strong enough and numerous enough to anchor those straps. It’s almost always up to the owner to add proper loops or eye bolts. The conundrum of where to locate them is rarely solved permanently. A few items such as the fridge might have a more or less permanent location, but the distribution of other gear is subject to change, and to the addition of new gear. Bolt in too many tie-down loops and they can be almost as much a hindrance as a help to properly securing stuff. Adjustable rails such as those from Mac’s Custom Tie-Downs add versatility; the anchor plate systems from the same company, which leave only an unobtrusive rounded base when not needed, are useful as well. But both of these need a fair amount of space to install.

A few years ago, while looking for tie-down loops for the rear of my FJ40, I found the Ring Products Transit Loops at Expedition Exchange. The stainless-steel loops were originally designed to be attached to motorcycles to provide easily accessible points on which to hook tie-down straps when transporting the bike on the trailer or in a truck. Lightweight and unobtrusive, they obviated the need to loop cinch straps awkwardly around handlebars or luggage racks. However, with my FJ40 in mind, I realized they looked just the right size to bolt down on top of the join between the body tub and hardtop, using the numerous existing 10mm bolts.

Indeed, such proved the case, and a half dozen of the rings gave me a solid perimeter tie-down system. I added a few more on the wheel wells, then started looking at our other vehicles and realizing there were a nearly infinite number of places the little rings could be utilized to secure a nearly infinite number of items. They could be installed in very tight spaces, and needed only a single 1/4-inch hole to mount. Visually, a pair didn’t look like overkill when securing something as small as a pack of road flares (with a bungee—a proper use for one), but four of them would lock down an Engel immovably.

And then the company went out of business. Damn.

I moved on to other tie-down systems for other projects—but how I missed those versatile little rings.

The fellows at Expedition Exchange apparently shared my thoughts, because after trying in vain for years to track down the Ring Products company or principals, they decided they’d exercised due diligence—and had a leftover reproduced at a local machinist. Skimming the EE website a few months ago, I noticed the newly introduced Expeditionware Transport Loops. Woohoo! I immediately ordered some to look at, and found them to be apparently exact copies. Excellent.

However, as I examined the new loops I found myself, for the first time, wondering about the ultimate strength of such a compact fitting. I’d always assumed that, since four of the originals were designed to hold down a motorcycle during road transport, they were certainly strong enough to secure a fridge or a Pelican case full of tools. But now I was curious about their limits.

With a loop in hand, I looked around our shop and carport for a way to put it to the test. I had neither a strain gauge nor a scale sufficient to register the several hundred pounds I assumed the loop would take before it failed. Bolt it to one of the steel roof beams in the carport and hang successive weights off it? Perhaps, but how to suspend 400—or 600 or 800—pounds in successive increments? Hook one between two Land Cruisers and try to pull it apart? But that wouldn’t tell us what the failure point was, and sounded like a procedure that would wind up either as an object lesson at the next Overland Expo, or a feature on YouTube.

With a loop in hand, I looked around our shop and carport for a way to put it to the test. I had neither a strain gauge nor a scale sufficient to register the several hundred pounds I assumed the loop would take before it failed. Bolt it to one of the steel roof beams in the carport and hang successive weights off it? Perhaps, but how to suspend 400—or 600 or 800—pounds in successive increments? Hook one between two Land Cruisers and try to pull it apart? But that wouldn’t tell us what the failure point was, and sounded like a procedure that would wind up either as an object lesson at the next Overland Expo, or a feature on YouTube.

But, hmm . . . the Land Cruiser. I looked at the rear bumper/tire carrier on the FJ40, specifically at the stout, one-inch-thick shackle mounts on either corner. Then I looked at the Hi-Lift jack nearby. That might do . . .

Using a grade 8 bolt and some graduated washers, I affixed the ring to the shackle mount via the smaller of its two holes. Then, with a steel quick-link connector through the larger hole, I attached the ring to the slot on the bottom of the Hi-Lift’s tongue, which I’d position just above the shackle mount.

Now I had a mechanism, but I still didn’t have a means of measuring the stress on the ring. Given that my FJ40 weighs a bit over 4,000 pounds, I decided rather arbitrarily that if I could lift one rear wheel off the ground—or even come reasonably close to doing so—the Expeditionware Transport Loop would have proved its mettle as far as I was concerned. I donned a heavy Carhart jacket, gloves, and safety glasses in case the ring exploded and flung bits of stainless steel hither and yon.

I began working the Hi-Lift’s handle and the loop took up strain. The assembly started to emit ominous metallic creakings, and for the first time I begin to wonder if this was a good idea. How could I expect a tiny ring a few millimeters thick to lift a corner of a 4WD vehicle?

The bumper rose, and the right rear leaf spring started to flex. Now, if I peaked around the Hi-Lift’s main beam, which I was keeping between me and the poor little ring, I could see the latter flattening. Was there some stretching going on as well? The sidewall bulge came out of the right rear tire as the bumper continued to rise with each stroke of the jack handle, but it remained planted on the ground. Now I could clearly see the large hole in the Transit Loop elongating. More creaking, and a ping or two from somewhere in there.

The bumper rose, and the right rear leaf spring started to flex. Now, if I peaked around the Hi-Lift’s main beam, which I was keeping between me and the poor little ring, I could see the latter flattening. Was there some stretching going on as well? The sidewall bulge came out of the right rear tire as the bumper continued to rise with each stroke of the jack handle, but it remained planted on the ground. Now I could clearly see the large hole in the Transit Loop elongating. More creaking, and a ping or two from somewhere in there.

But then—the tire was a few millimeters off the ground. I could spin it with a boot. A single Transit Loop had successfully lifted the corner of an FJ40 off the ground—and one equipped with a massive Stout Equipment bumper/tire rack at that.

I have no way of knowing exactly how much strain the loop was withstanding at the end, but I’m certainly convinced that, employed in suitable numbers, the Expeditionware Transit Loops are more than up to the job of safely locking down the heaviest fridges, tool boxes, and equipment cases.

At nine bucks each you can afford to buy a bunch. I guarantee you’ll find uses for as many as you have.

Unless you’re still convinced a bungee or two will suffice. Expeditionware Transport Loops

Long Term Review: First Gear Monarch motorcycling jacket and Escape pants for women

A couple of years ago I conducted an extensive review of armored motorcycling jackets suitable for touring and off-pavement riding. The selection ranged from a budget, Chinese-made, $300 offering from Fieldsheer to an outrageously exquisite $1,300 Rukka from Finland, presumably sewn by organically grown virgins in Helsinki.

A couple of years ago I conducted an extensive review of armored motorcycling jackets suitable for touring and off-pavement riding. The selection ranged from a budget, Chinese-made, $300 offering from Fieldsheer to an outrageously exquisite $1,300 Rukka from Finland, presumably sewn by organically grown virgins in Helsinki.

A bit up from the bottom of the pack pricewise was a First Gear Rainier, a $400 jacket made in Vietnam. It stood out in value with its combination of good quality and looks, comfortable armor, and effective waterproofing. Based on those initial impressions, Roseann decided to order a women’s Monarch jacket and Escape pants from the company. She’s now had two years and two motorcycles worth of time wearing the set, and we decided to do a long-term update.

A couple of years ago I conducted an extensive review of armored motorcycling jackets suitable for touring and off-pavement riding. The selection ranged from a budget, Chinese-made, $300 offering from Fieldsheer to an outrageously exquisite $1,300 Rukka from Finland, presumably sewn by organically grown virgins in Helsinki.

A couple of years ago I conducted an extensive review of armored motorcycling jackets suitable for touring and off-pavement riding. The selection ranged from a budget, Chinese-made, $300 offering from Fieldsheer to an outrageously exquisite $1,300 Rukka from Finland, presumably sewn by organically grown virgins in Helsinki.

A bit up from the bottom of the pack pricewise was a First Gear Rainier, a $400 jacket made in Vietnam. It stood out in value with its combination of good quality and looks, comfortable armor, and effective waterproofing. Based on those initial impressions, Roseann decided to order a women’s Monarch jacket and Escape pants from the company. She’s now had two years and two motorcycles worth of time wearing the set, and we decided to do a long-term update.

An adventure-motorcycling jacket must strive to combine several features that are mutually exclusive. It must be warm in cold weather and cool in hot weather. It must be able to resist not just rain, but rain driven at 60mph or more, while allowing flow-through ventilation in sunny conditions. It must protect the wearer against abrasion and impact forces in a laydown on a trail or a more serious accident on pavement, while retaining freedom of movement and comfort, and avoiding bulk. Finally, it’s nice if the package looks good.

Obviously no jacket combines all these features perfectly. A Motoport Ultra II jacket in that first test boasted unequalled crash protection, but was so bulky that, as I mentioned at the time after looking in a mirror at my bloated profile, “Entomologists will think you’re pupating.”

On the other end of the fashion scale was the legendary waxed-cotton Barbour International, which lends anyone who dons it a rakish hint of Steve McQueen but which lacks any armor whatsoever. So picking a motorcycling jacket is a matter of deciding on one’s own priorities, up to and including style, while also keeping in mind keeping one’s mortality and fragile, evolutionarily compromised anatomy.

I was leery about including First Gear at the time of that review, since the company had been through several changes of ownership. But the current management, motorcycle equipment distributors Tucker Rocky, apparently had cracked the whip and gotten a handle on quality control. Roseann’s experience seems to confirm that—her jacket and pants have held up well, showing no fraying stitching, failing DWR (durable water-repellent) coating on the exterior, or even pilling on the fleece neck lining. Only the slightest wear on the inside of the knit cuffs is apparent.

In terms of performance, the rundown she gave me while I took notes adds up to a grade of about a solid B.

The Monarch and Escape on its first tour, two years ago, during a March southern Arizona dirt-and-pavement weekend.First, she noted that the jacket really does seem to be cut for women in the shoulders, arms, and torso; it’s not merely a men’s small masquerading as gender-specific.

The Monarch and Escape on its first tour, two years ago, during a March southern Arizona dirt-and-pavement weekend.First, she noted that the jacket really does seem to be cut for women in the shoulders, arms, and torso; it’s not merely a men’s small masquerading as gender-specific.

Significantly, she mentioned that she’s able to forget the Knox CE-rated shoulder and elbow armor while riding; some armored jackets I’ve worn (such as that Motoport) never let you do so. Her only note was that the jacket’s arms fit somewhat loosely on her 115-pound frame even with the two Velcro cinch straps pulled all the way tight, resulting in some flapping at speeds over 110 mph. I think she was kidding about that last bit.

The pants, while also very comfortable around their armored hips, weren’t quite so forgettable in the knees: When in a normal riding position, Roseann found she needed to slightly hitch up each leg to arrange the knee armor comfortably on top of her knee rather than binding below it. This might be a personal fit issue, but it points out the importance of trying on armored cycling clothing before buying it if possible. Fortunately the knee issue is a small and correctable one.

Roseann rated ventilation in the Monarch as “adequate.” A seven-inch zippered vent in front of each shoulder lets in the breeze; corresponding vents in back let it out again. Small vents behind each sleeve add a bit of air movement up the arms. Considering Roseann’s Arizona-native tolerance for heat and preference for riding in the desert summer, I’d guess her “adequate” means ventilation in the Monarch could be slightly better.

There are two approaches to the conundrum of rain protection versus ventilation in motorcycling jackets. One is to make an outer armored jacket of breathable or even mesh material, and employ a separate inner waterproof (and frequently insulated) shell for dryness. This works well for mostly dry environments, but the waterlogged outer shell can become annoying if  Lacking sufficient reflective tape, Roseann opts to wear a safety vest when riding pavement; the pants' knee pads are a little low, and have to be manually adjusted each time the bike is mounted.experienced too frequently.

Lacking sufficient reflective tape, Roseann opts to wear a safety vest when riding pavement; the pants' knee pads are a little low, and have to be manually adjusted each time the bike is mounted.experienced too frequently.

The other approach is to make the outer shell waterproof, and ventilate it as well as possible with covered or waterproof zippers. The latter is the approach First Gear took; the Monarch is waterproofed with an interior coating of minimally breathable polyurethane (dubbed “Hypertex”) and an outer DWR coating.

Nevertheless, the company includes an inner shell incorporating a three-layer waterproof laminate (and a fleece lining). The outer jacket on its own has proven completely rain-tight so far. The inner jacket is stylish enough to be worn on its own, a good addition to kit for long journeys where you might need a jacket for visiting museums or restaurants.

With nary a spill to her credit, Roseann is in no position to rate the crash effectiveness of the Monarch and Escape. On paper, however, the specs look good. Both jacket and pants are sewn from 600-denier nylon, a step above the 500-denier fabric generally accepted as the minimum for adequate abrasion resistance. Kevlar underlay at knees, shoulders, and elbows should help prevent fabric tearing in an accident (Kevlar fibers resist shearing but, surprisingly, nylon is more abrasion-resistant). The CE-rated (Conformité Européenne) shock-absorbing armor is generously sized in the same three areas; a simpler closed-cell-foam pad adds some protection on the back.

On details and convenience, Roseann had nothing but praise. Pockets on both jacket and pants are plentiful, easy to access, and well-sealed with storm flaps or YKK water-resistant zippers. An MP3/phone pocket is completely protected inside. Jacket and pants zip together, enhancing both draft protection and safety in a fall and slide on pavement (when an unsecured jacket can ride up and expose skin).

All in all, Roseann’s experience with the Monarch and Escape seems to have reinforced the favorable impression my brief time with the Rainier left with me. First Gear has produced an affordable, yet comfortable and protective set of outerwear that should hold up well to extended riding.

Even if it’s not sewn by organically grown virgins in Helsinki.

* * * * * * * * * * *

First Gear Monarch Jacket, msrp $470 (5-year warranty, 2-year crash protection policy). Three colors, sizes XS-XXL. Men's equivalent: Teton Jacket. Now includes LED light that clips on back.

First Gear Escape Pant, msrp $380 (5-year warranty, 2-year crash protection policy). Black, sizes 6-18. Also in Men's. Now includes inner liner pant.

Equipment review: micro stoves, part 1 of 3

Let’s be frank here: Adventure motorcyclists are essentially divided into two species—those who ride a BMW R1150GS or R1200GS, and those who ride anything else (including other BMWs). We can argue about whether or not the big GS bikes are the best adventure motorcycles on the planet, but you can’t deny they’re the most prominent, and their fans make the most zealous Sturgis-tattooed Harley rider seem fickle.

Let’s be frank here: Adventure motorcyclists are essentially divided into two species—those who ride a BMW R1150GS or R1200GS, and those who ride anything else (including other BMWs). We can argue about whether or not the big GS bikes are the best adventure motorcycles on the planet, but you can’t deny they’re the most prominent, and their fans make the most zealous Sturgis-tattooed Harley rider seem fickle.

To continue the Linnaean angle, the mega-GS riders I know generally separate into two sub-species when considering camping equipment: They either think, I’m riding a zillion-pound motorcycle. What difference does it make what my equipment weighs? Or, I’m riding a zillion-pound motorcycle. I need to save every gram I can on equipment.

If you’re a member of the former group, and you’re in the market for a stove, I can happily recommend a three-burner Partner Steel model, which will strap on your rear luggage rack with room to spare. A 20-pound propane tank should give you plenty of cooking fuel. For the latter group—or any of you who ride mere mortal motorcycles, I offer a review (the first of three, with a final winner to be chosen) of two micro stoves.

Let’s be frank here: Adventure motorcyclists are essentially divided into two species—those who ride a BMW R1150GS or R1200GS, and those who ride anything else (including other BMWs). We can argue about whether or not the big GS bikes are the best adventure motorcycles on the planet, but you can’t deny they’re the most prominent, and their fans make the most zealous Sturgis-tattooed Harley rider seem fickle.

Let’s be frank here: Adventure motorcyclists are essentially divided into two species—those who ride a BMW R1150GS or R1200GS, and those who ride anything else (including other BMWs). We can argue about whether or not the big GS bikes are the best adventure motorcycles on the planet, but you can’t deny they’re the most prominent, and their fans make the most zealous Sturgis-tattooed Harley rider seem fickle.

To continue the Linnaean angle, the mega-GS riders I know generally separate into two sub-species when considering camping equipment: They either think, I’m riding a zillion-pound motorcycle. What difference does it make what my equipment weighs? Or, I’m riding a zillion-pound motorcycle. I need to save every gram I can on equipment.

If you’re a member of the former group, and you’re in the market for a stove, I can happily recommend a three-burner Partner Steel model, which will strap on your rear luggage rack with room to spare. A 20-pound propane tank should give you plenty of cooking fuel. For the latter group—or any of you who ride mere mortal motorcycles, I offer a review (the first of three, with a final winner to be chosen) of two micro stoves.

We've Come a Long Way

My first backpacking stove was a beautiful little white gas SVEA 123, considered “light” at the time despite being made from solid brass, which has a density not far this side of neutron star core material.

How times have changed. Compare the 18-ounce heft of that SVEA with the 1.9 ounces of a Snow Peak LiteMax Titanium stove. Sure, the LiteMax has no built-in fuel tank, but add a full canister of isobutane/propane mix and you’re only up to 8.5 ounces, less than half the mass of the empty SVEA.

However, as important as weight is to a motorcycle traveler, it’s not the only consideration when choosing a stove. Stability, efficiency, wind resistance, boiling time, and simmering ability all factor in as well.

Furthermore, weight can be deceptive. Canister stoves are virtually always lighter than liquid-fuel stoves even with a canister attached, since they require no pumping mechanism—but for most trips you’ll need more than one canister, and the weight (and bulk) of them adds up quickly.

Then there’s disposal: Recycling spent canisters is an on-again, off-again possibility in many communities. Sometimes they’re just trash. (JetBoil makes an excellent tool for puncturing empty canisters, required for recycling in most areas.)

First in a Series of Stove Duels

I decided to take a highly opinionated, who-made-you-the-expert? stab at pronouncing which is the best lightweight stove on the market. However, rather than review every single one of the dozens of models available, I’m cheating a bit—I’ve chosen what fairly broad experience has led me to believe are:

- Two of the best top-mounted canister stoves

- Two of the best remote-canister stoves, and

- Two of the best liquid-fuel stoves.

The winner of each duel will face off in the final.

I looked at top-mounted canister stoves first. The major advantages and disadvantages of this style can be summarized thusly:

Advantages:

- Extremely lightweight and compact

- Extremely simple to assemble and operate

- Quiet and clean-burning

- Excellent simmering ability

- Most affordable to purchase

Disadvantages:

- Least stable of three stove types

- Marginal cold-weather performance even with mixed fuel

- Canisters are bulky on long trips

- Susceptible to wind (and care must be used with wind deflectors to avoid overheating of the canister)

- Generally slower boil times than liquid-fuel stoves (although speed of assembly and lighting compensates)

- Difficult to quantify remaining fuel

- Fuel costs are higher

- Canisters often not available in developing countries

Of all the top-mounted canister stoves I’ve used, I like the Primus Express Stove and the Snow Peak GigaPower the best, for their light weight, simplicity, and affordability.

Primus Express Stove (on Snow Peak canister), $54

Primus Express Stove (on Snow Peak canister), $54 Snow Peak Gigapower (above right), $40 ($50 w/pietzo)

Snow Peak Gigapower (above right), $40 ($50 w/pietzo)

The Express also comes in a titanium version, but the scant .4 ounce saving (2.5 versus 2.9) isn’t worth the extra $20 to me—that’s a set of titanium utensils which would save more weight. Snow Peak has the fine newer (and slightly lighter) LiteMax, but I prefer the four-trivet stove base on the GigaPower, and it folds more compactly as well.

There are other good stoves out there. The JetBoil is absolutely fabulous at boiling water quickly, but I find the system cumbersome for general cooking duties, and even its titanium versions are fairly heavy. The MSR Pocket Rocket was a contender, only passed over because—just once—I had one of its three trivets fold up on me while I was setting a pot on top, and almost lost the whole thing. Another near miss was the Optimus Crux Lite—an excellent stove that is a champ at simmering, except I’ve occasionally had the flame die unnoticed when on its lowest setting.

So—let’s decide between these two. Both are designed to use standard Lindal-valve canisters, and each company’s proprietary canisters contain an isobutane/propane mix, which enhances low-temperature performance (pure propane would be best as its boiling point is -40ºF versus butane’s +31ºF, but pure propane requires a stout steel canister).

Snow Peak Gigapower (above right)Weight difference is negligible: 3.25 ounces for the Snow Peak versus 3 ounces for the Primus. However, my Primus includes a piezo igniter; the equivalent GigaPower is 3.75 ounces. So a slight .75-ounce nod goes to the Primus here.

Snow Peak Gigapower (above right)Weight difference is negligible: 3.25 ounces for the Snow Peak versus 3 ounces for the Primus. However, my Primus includes a piezo igniter; the equivalent GigaPower is 3.75 ounces. So a slight .75-ounce nod goes to the Primus here.

Both stoves are effortless and speedy to employ. Less than 30 seconds out of the stuff sack for either and you’re cooking.

I timed boiling for each, using 500 ml of water (note my commitment to scientific rigor by using 500 milliliters rather than a crude pint) in my favorite do-it-all solo pot/kettle/bowl, an MSR titanium Titan.

The GigaPower accomplished the task in 3 minutes, 13 seconds; the Primus was slightly quicker at 3 minutes, 7 seconds. Again, a slight nod to the Primus. (I used Snow Peak canisters for both to eliminate differences in fuel. I suppose Primus could protest, but since their stove was faster anyway . . .) Both stoves simmer extremely well, but the burner of the GigaPower spreads the flame over a wider area, so it wins there.

Stability on top-mounted canister stoves is marginal at best. You should always provide a flat, firm surface for this type of stove. (I discovered the Snow Peak Baja Table while I was sea kayaking. It’s a cunning aluminum contraption that’s just high enough to get food prep and cooking off the ground, and which doubles elegantly as a cocktail table for a Kermit Chair.)

The Primus has a wider trivet assembly then the GigaPower, but the latter has four trivets versus three, which I find adds security. More importantly, the Primus, at 14.5 centimeters tall, sits 1.8 cm higher than the Snow Peak—almost three-quarters of an inch. That might not seem like much, but with these tippy stoves every bit helps. Win to Snow Peak.

What else? The wire-loop valve on the Snow Peak sticks out farther than the plastic knob on the Primus, so you don’t have to get your hand so near to the flame to adjust it. Both stoves fold very small, but the GigaPower collapses into a symmetrical shape, while the three trivets on the Optimus protrude somewhat even when folded, creating slightly awkward storage inside a pot.

Since I already knew I liked both these stoves, choosing between them was difficult. I’d happily carry either, and do. But when the time came to pick one, my hand finally strayed to the Snow Peak GigaPower. Its balance of features and performance tipped the scales ever so slightly.

Next time we’ll look at two of the best remote canister stoves on the market.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.