Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

The Wescotts return from The Silk Road

One day in the summer of 1993 Roseann and I were sitting in a café in the Canadian Inuit village of Tuktoyaktuk, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. We’d been having one of those time-warp conversations with a phlegmatic local whale hunter: He’d ask a question such as, “Where you from?” We’d answer, there’d be a two-minute silence, then, “How’d you get down the river?” We’d answer, then ask him a question: “Lived here long?” Two minutes, then, “Born here.” We were in no hurry, having just paddled sea kayaks 120 miles to get there, so it was a fun way to pass time and—slowly—learn something of the area.

After a while a couple came in—anglos, surprisingly, the first we’d seen since landing the day before. They sat nearby and said hello, and we struck up a conversation that must have seemed alarmingly hasty to the Ent-like whale hunter. They asked how we’d got to Tuk, and when we described our trip expressed open-mouthed admiration. They’d flown from Inuvik, it developed, and had left their pickup and camper there.

And as soon as they mentioned a truck and camper, I realized that the couple was Gary and Monika Wescott. It was my turn to be open-mouthed, as I’d been reading tales from the Turtle Expedition in Four Wheeler magazine for, what, 15 years already by then? I’d devoured the articles documenting the extensive modifications to their Land Rover 109 during the 1970s, had been disappointed but intrigued when they switched to a Chevy truck (which, even more intriguingly, vanished without comment soon after), and then followed the buildup of the Ford F350 that would prove to be the first of a series. Our Toyota pickup had a Wildernest camper on it at the time, but we were saving to buy a Four Wheel Camper of the same type that sat on the F350 Turtle II. Most recently, I’d read along as the Turtle Expedition completed an epic 18-month exploration of South America.

We saw each other over the next couple of days as we all took in the annual Arctic Games, watching harpoon-throwing contests and blanket tossing, and snacking on muktuk. Then we lost touch for 15 years (while they journeyed across Russia and Europe), until reconnecting when I edited Overland Journal.

Since 2009 the Wescotts have been regular instructors and exhibitors at the Overland Expo—until 2013, when they embarked from the show on their latest adventure, a two-year trans-Eurasian odyssey along the Silk Road.

Now we’re delighted to welcome Gary and Monika back from their journey. They will be giving presentations and taking part in roundtables at Overland Expo WEST 2015. Don’t miss a chance to meet these two personable and friendly travelers. Listening and watching as the Wescotts describe their journeys is both entertaining and inspiring, and their latest journey should be fertile ground for good tales.

Best of all, Gary and Monika are genuinely excited to share; there’s not a trace of bravado between them, despite being among the most-accomplished overlanders in the world (and still traveling). They travel because they are passionate about exploring and learning and sharing, not because they are trying to count coup or gain fame. It’s refreshing, and we are glad to have them back.

- Regional Q&A: Russia, Mongolia & Southeast Asia; Friday 2pm

- Regional Q&A: Europe, Eastern Europe & Iceland; Saturday 8am

- The Silk Road; Saturday 11am

- Experts Panel: Top Travel Tips; Saturday 1pm

Explore 40 years of adventures with the Turtle Expedition at http://turtleexpedition.com

The Tacky Tourist Mug

Humans have been collecting souvenirs to commemorate their travels for a long time.

Amber beads from Scandinavia, found in Ireland and dated to around 1,000 BC, are among the first objects to be classified as ‘souvenirs’ by archaeologists—probably because the scientists could figure out no practical use for them, the very definition of a souvenir. By the middle of the first millenium AD, religious authorites in Europe had become so tired of pilgrims breaking off pieces of holy buildings and statues to take home that they began manufacturing and handing out tiny ampullae filled with holy water to stem the vandalism. These soon proved too expensive to produce in mass quantities, so cheaper badges were substituted. Thus we can blame the church for the rows of junk in most modern gift shops.

Wealthy nineteenth-century travelers on the Grand Tour of Europe commonly had compact portraits painted of themselves next to famous landmarks such as the Arc de Triomphe. Anyone else see a direct line of descent to the selfie stick?

These days, as mentioned, the word ‘souvenir’ generally calls to mind Elvis snow globes (the largest gift shop in the world is in Las Vegas), Chinese Inca figurines, and T-shirts. Yet the drive to take home some essentially inconsequential memento of exotic travels remains strong in us. How to assuage it without becoming an item of ridicule in the local paper on one’s death?

Roseann hit upon an excellent solution a few years ago, on a trip to Egypt. We’d hired Land Cruisers with camping and cooking equipment, but the only cups included were plastic throwaways. In a parking lot near the Pyramids she scanned the offerings of a group of vendors, and picked out a spectacularly hideous mug with Pharaonic motifs done in gold leaf. I chided her for contributing to the Chinese-ification of the souvenir trade until she turned it over and found it was made right there. And she had a nice ceramic mug for the rest of the trip, while I drank coffee from Dixie cups (we never found another souvenir mug dealer).

That mug (which she referred to as her ‘tacky tourist mug’), judiciously packed, made it home, and a tradition was born. Now we have an ever-expanding collection of mugs from destinations as diverse as Ushuaia and Steamboat Springs. While some remain decidedly on the tacky side—witness the Pope Mug from Argentina—many others simply commemorate a favorite town or cafe. And we never run out of coffee mugs for visitors.

Silent impressions of the Overland Expo

Kyle's overlanding setup

By Kyle Rosenberg

Last summer the following post appeared on a popular overlanding forum:

“If you were engaged in an activity or gathering, such as, say, the Overland Expo, or an expedition in which a group effort were necessary to get from point A to point B, who do you feel would be a more challenging travel companion: 1) An international traveler who neither speaks, reads, or writes English, or 2) A deaf person who is fluent in English but cannot speak, hear, or understand English and relies on American Sign Language as his primary means of communication?”

The responses I got to this informal survey appeared to be split three ways, which was what I expected. Some said interacting with the international traveler would be easier, some said the deaf individual, others said it made no difference. It was fascinating to see the rationale many shared for why they chose what they did, and the experiences they had had with one or the other group, both, or neither. I did not disclose to anyone on the forum that I am a bilingual deaf person, so, with the exception of one or two people who replied who had met me previously, this allowed me to collect completely objective perspectives.

With the idea of an experiment forming in my mind, I reached out to Jonathan and Roseann Hanson of Overland Expo to share my thoughts. Since I can lip-read very well, I wanted to try the full Overland Experience package of classes. As we emailed back and forth, however, we decided that I should try even greater immersion. So not only did they sign me up for the Overland Experience package at the upcoming Overland Expo EAST, I also signed up to be on the volunteer crew so I could experience everything there from both perspectives, the attendee and the volunteer. What follows are just a few experiences out of the many I had during the first week of October.

I arrived in Asheville on the Monday before the Expo to start working with the other volunteers and individuals who make up the Overland Expo organization. We spent the next few days transforming Taylor Ranch into what I saw as an overlanding utopia, and in the process I got to know many of the people there, ‘listening’ to their stories and experiences whilst they got to know me and my unique views on the world as a fully-functioning disabled person. Needless to say, it was this group of people I was most comfortable interacting with for the remainder of the week, as they had become comfortable with me and developed their own methods for interaction, whether it was gesturing, speaking slowly and clearly, or picking up on nonverbal cues to adjust seamlessly the prosody of our communication.

Whether it was intentional or a happy coincidence, I was assigned to direct traffic on Thursday, when the majority of the attendees arrived. My location at the midway point on the hill ensured that nearly everyone who camped at and beyond the hill interacted with me throughout the day. While the job was simple and usually did not require more than directions, which I could do happily just pointing my finger, several times I was asked about certain group rendezvous areas, and about showers and toilets. I understood people just fine, as I’m an expert at lip-reading and I often use the power of deduction to figure out what is being said. However, strangers struggle to understand me as it takes time to get accustomed to my unique deaf “accent” when I struggle to pronounce words correctly. A 30-second interaction makes it virtually impossible to accomplish this. Some people reacted much better than others. Some understood me just fine, while others got frustrated and just rolled on to the next person up the hill. I observed a distinct difference in reactions among different ages: Older individuals seemed much more willing to try to understand and interact with me, while younger folks were much more impatient and less considerate. Hmm, something to ponder here!

Come Friday, the Expo had officially started, and part of my experiment was to sign up for as many classes as I could (I believe 11) in several formats, to see which was the most accessible for me, to observe what worked and what did not. I signed up for classes, narratives, slideshows, demonstrations, and roundtable discussions. My observations—obviously slanted by my own cirsumstances—are listed below.

Some narratives were great; others not so. Those who were passionate and animated about their experiences were easy to understand, as the picture they painted of their trips came to life and the vividness of their words made me feel as if I were there. Those speakers also made eye contact with the audience, and this allowed the speaker to adjust his pace and focus of elaboration. But a few just sat, spoke in a monotonous manner, and actually looked downward the entire time and did not use any visual aids. Perhaps those individuals were not used to public speaking, which is understandable but did not benefit me much in the information-gathering process. For someone as dependent on visual cues as I am, this will make or break the whole experience.

All the slideshows I went to I enjoyed immensely, as I was able to reconcile the objectives of the speaker to each picture that appeared as they were set up in a linear fashion, a pathway from the beginning to the end, if you will. It was quite easy to follow, as it is a natural tendency for presenters to point to certain areas or objects in the picture and then expand upon it. That is what I used to determine the content/context of the talking points.

Demonstrations were another favorite, since not only did I get the chance to see how certain things were accomplished in a step by step manner, it was hands-on which speaks to my background in Experiential Education—the philosophy of learning by doing. It also worked in my favor as demonstrations have a built-in pace that allows for clarification and audience participation.

I did not enjoy panels and roundtable discussions as much as the others, because it was extremely difficult to follow along. Often people in the audience would ask questions, and by the time I figured out where it was coming from, the question had already been asked and the answer was in progress. As is often the case with having a few experts on a particular subject, they sometimes talk over each other. As they expand on the person speaking before them, if that is missed, it becomes a snowball effect and the delay in information only gets larger and larger.

What I learned from this experience is that it is much easier to communicate with people one-on-one rather than in a group setting, as I can put in all of my resources to make sure they’re understood instead of jumping around and “resetting” every time someone new participates. It’s exhausting after a while trying to follow everyone as it takes quite a bit of processing in such a short time.

Interestingly enough, the biggest obstacle I had during the weekend was something as simple and natural as nightfall. With little or no light, I can’t read lips. If I can’t read lips, it goes without saying that I’m not going to be able to understand anyone. Even with a roaring campfire, it sure does get extremely dark in the Blue Ridge Mountains!

I’m hoping that I’ll be able to make it out to Arizona for Overland Expo West 2015, but I have yet to decide if I want to reprise the experience I had in Asheville—which was fantastic—or see about bringing a friend who is fluent in sign language and would be willing to interpret the classes and the presentations so I can engage fully, instead of merely being an observer. The overland travel bug has truly bitten me and I intend to embrace it as much as I possibly can.

I want to thank everyone I came across during the week I spent in Asheville. From the time I showed up at the Wedge Brewery for the pre-expo social to the Monday morning cleanup of Taylor Ranch, it was a phenomenal experience that I’ll never forget. The people I met, interacted with, worked with, and shared with are way too numerous to be listed here, but you know exactly who you are.

Kyle Rosenberg currently resides in New Jersey but his heart is in the desert southwest. His vehicle of choice is a 4Runner that is always full of gas and a 1950 Bantam trailer with a roof top tent ready at a moment’s notice to be hitched to travel and explore what the country has to offer. A recent graduate of the Masters Program in Experiential Education at Minnesota State, Mankato, he is currently exploring progressive and innovative bilingual ways of combining the overlanding experience with educational programming for everyone to enjoy whether they are disabled or able-bodied. This will hopefully be achieved through team-building activities, experiential learning approaches and educational outreach. Any and all ideas, proposals, job opportunities, and networking, along with a couch or backyard to visit, are welcomed and greatly appreciated. He can be reached at kylemrosenberg@gmail.com.

Where quad-cab pickups rule

South America could be referred to alternatively as The Land of Quad-Cab Pickups. In the 6,000 miles we drove, the proportion of quad-cab models to standard cabs was at least fifty to one, if not greater.

The manufacturer range is extraordinarily broad. In Argentina, Chile, and Peru, the Toyota Hilux predominates in spite of its age (little changed since 2005). Manufactured in Argentina, it’s normally powered by the 1KD-FTV 3.0-liter four-cylinder turbodiesel, a bombproof powerplant that takes advantage of significantly cheaper diesel fuel prices here, but is beginning to lag in the power department with 172 hp and 260 lb.-ft. (A redesigned Hilux will soon be entering the market, but reports are that engines will be largely held over.)

Two other brands offer newer models arguably superior to the Hilux, at least on paper. The handsome Ford Ranger T6 has a 3.2-liter turbodiesel that produces significantly more power than the Hilux (197 hp and 346 lb.-ft.) ; the Ranger also boasts a greater fording depth.

The Volkswagen Amarok (which means ‘wolf’ in Inuit—and we get the ‘Tacoma’?) manages up to 177 hp and 310 lb.-ft. from a tiny but hyper-efficient two-liter turbodiesel. Despite their more modern design, neither the Ranger or Amarok seems to have cut far into Hilux sales. We also saw a few of the new and impressively specced Chevrolet Colorados, set to give the U.S. Tacoma some competition.

The Mitsubishi Triton appeared to be the second-most popular truck in a lot of areas, despite its (to me) ungainly styling and middling turbodiesel. Speaking of ungainly, in Chile the Mahindra is extremely popular, and I have to admit its wonky looks are growing on me—it’s definitely styling by Bollywood compared to Detroit’s Hollywood, but I like the huge window area.

Much more conservative is the Great Wall Wingle 5—the Chinese managed to combine an awesome brand name with an utterly dorky model name (but then there’s ‘Tacoma’ . . .). How long will it be before a Chinese vehicle manufacturer mounts a serious import campaign in North America?

Korean manufacturer Ssangyong fields a stylish pickup called the Actyon Sports. With all-coil suspension and a long list of family-friendly features, it appears to be aimed at a more urban audience.

Finally, we spotted just an example or two of a mid-size truck called the Xenon from Tata, the Indian megacorporation that owns Land Rover and holds the fate of the Defender in its hands.

And, we had some indication that the South American fondness for quad-cab pickups is perhaps not a recent phenomenon:

JATAC update: After a near-death experience

One afternoon early last year I was driving the JATAC, our Tacoma/Four Wheel Camper combination, west on Arizona’s Highway 86—a two-lane, 65mph road flanked with emergency lanes. As I approached a side road coming in from the north, I saw a Subaru sedan waiting at the stop to turn east, across my lane. Meanwhile, an SUV in front of me put on its signal and pulled into the turn lane to turn north. As I passed the SUV, the driver of the Subaru, who had apparently missed seeing the white pickup and cabover camper headed his way, accelerated, pulled out in front of me—and then stopped as he saw what he’d done. This left me heading toward his door at 60mph-plus, about 50 feet away.

In one of those slowed-down time-warp instants I saw with utter clarity the driver’s face, looking at me with the open-mouthed certainty that he had just committed suicide. There was scant chance I could avoid hitting him. Braking would have been laughably futile. The only possible alternatives were the desert on the right or, across the oncoming lane, the desert on the left. I saw there was no opposing traffic, so I violently yanked the steering wheel left, clearing the front of the Subaru by what could only have been inches. On the edge of either sliding or rolling—I wasn’t sure which—I yanked the wheel the other way, corrected a violent yaw, and managed to keep the truck on the pavement in the oncoming emergency lane, where I slowed, checked traffic (the Subaru had fled—you're welcome, pal), and pulled across again to stop off the road and restart my heart.

I got out and checked the truck and camper. Everything seemed okay, so I continued home. But on the last rough dirt section I heard a faint but obvious rattle coming from the camper area. At home I investigated and found that one of the four turnbuckles securing the camper to the truck had split at the open hook. I’d been meaning to replace the stock, aluminum-bodied turnbuckles anyway, and took the opportunity to install forged steel replacements.

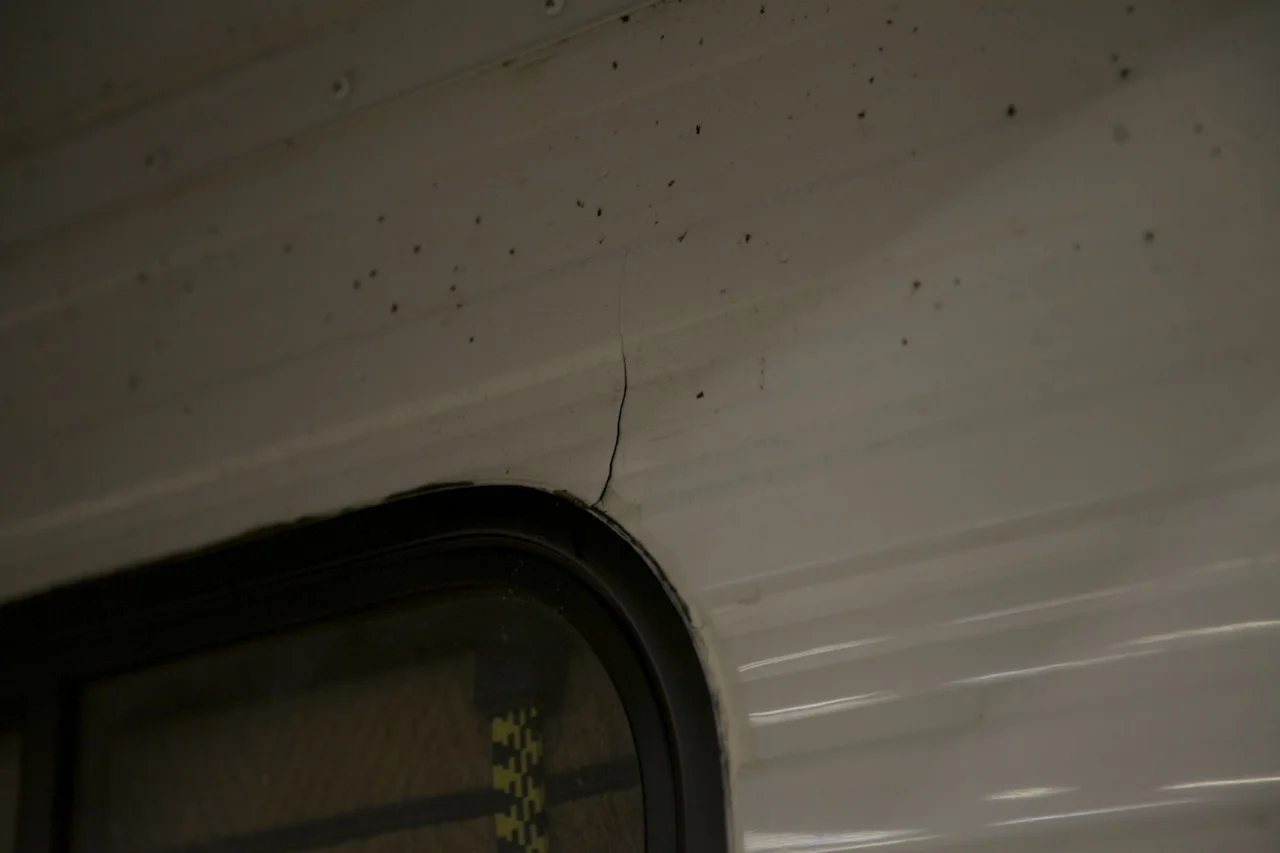

That seemed to be the end of the matter. However, several months later while washing the truck I noticed a split about two inches long in the camper’s aluminum skin, extending from the upper right corner of the front window, behind the truck’s rear window. Investigation revealed a similar split on the opposite side. Could the near miss have been the genesis of the splits? Difficult if not impossible to say, but it was a worrisome development.

I showed the splits to Tom Hanagan of FWC at Overland Expo EAST, who urged a factory visit to remove the skin and investigate the possibility of a cracked frame member or weld. So this Christmas we combined visit to see family on Coarsegold, California, with a trip to the Four Wheel Camper factory in Woodland. We took the opportunity to have a couple of upgrades done to the camper—the company is constantly evaluating current systems and components, looking for ways to improve the product.

As you can see, the splits would be easy to miss if you weren't paying attention. Between the time I noticed them and the time we got to FWC, they seemed to have remained more or less stable.

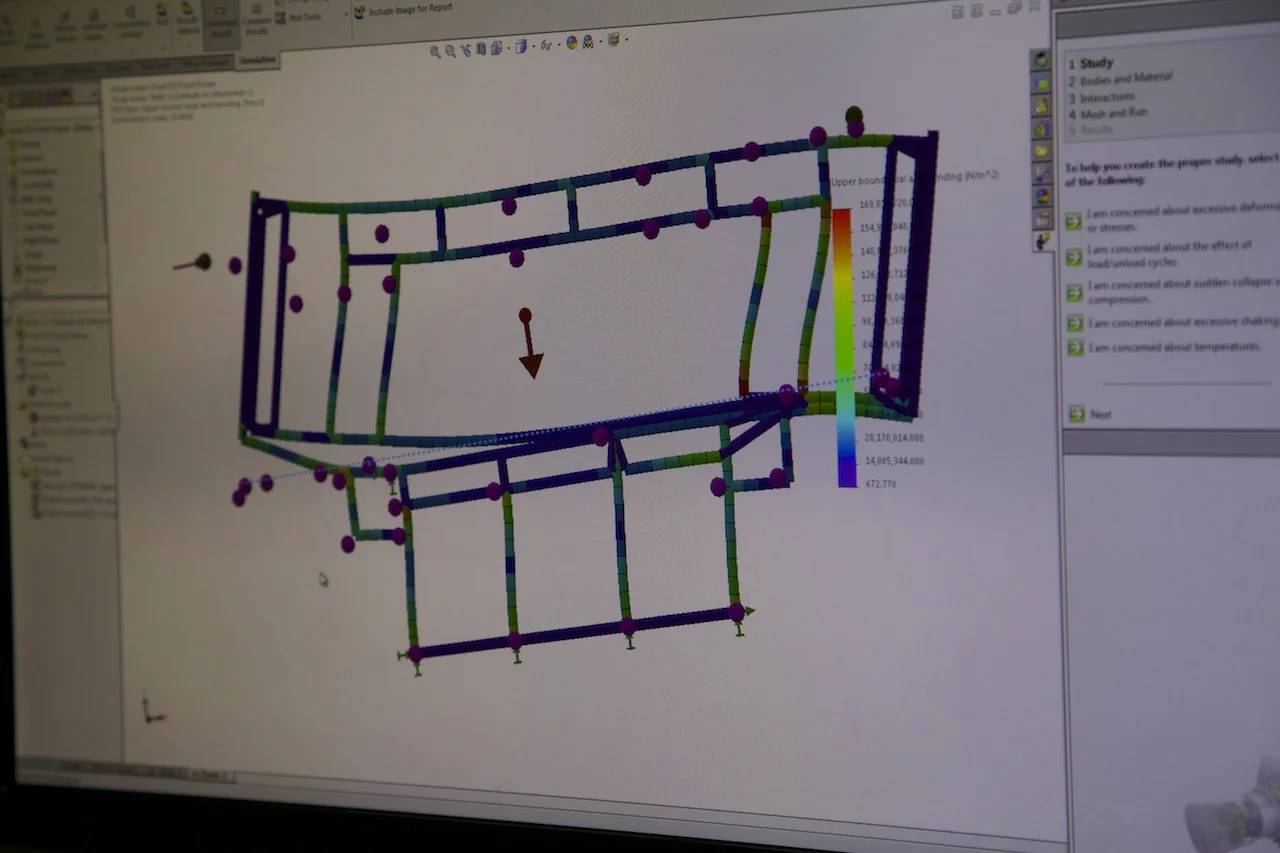

With the front skin removed, Tom Hanagan inspected the frame, but found no cracked welds or any other damage. He had only seen this issue a couple times previously, but nevertheless decided that further structural engineering might be worth investigating. So I went upstairs with Robin Pritchard, FWC's new engineer, and watched while she created a CAD image of the Four Wheel Camper's front frame structure.

Once the virtual frame was assembled on screen, Robin applied a significant simulated side load. With no other structure or skin to reinforce the isolated frame, and the distortion effect magnified hundreds of times by the program, the graphic showed that the area of highest stress occurred . . . at the top corners of the window opening.

Robin studied the image for a minute, then applied a simple boxed reinforcement on either side of the window opening with a few clicks of her mouse. Immediately the distortion was attenuated, and the angry red color that highlighted stresspoints cooled off to a benign yellow. Tom looked at the result, and rolled our camper over the the welding area of FWC's huge factory, where the fabricators welded in two channeled aluminum pieces on our frame. The entire process added perhaps six ounces to the weight of the camper.

With the reinforcements in place, Jay Bailey re-positioned the rigid foam insulation, and installed a new front skin.

Very soon the front of the camper looked new again. Despite the uncommon nature of this issue, Tom has incorporated the reinforcement into all new campers that have the forward dinette. He is also currently testing a new, forged turnbuckle that I think will be a significant improvement in the anchoring system.

Repairs completed, we had FWC install external roof-lifting struts on the front and rear of the camper. With only the single internal pair of struts, Roseann had trouble lifting the back of the roof when we set up the camper. She has no trouble with the external struts, and eliminating the internal pair cleaned up the interior appearance and added room on the bed. FWC also installed a new style table in the front dinette; with a simpler, stronger, and more elegant swivel.

Soon the camper was back on the Tacoma, looking visibly chuffed after its little spa facelift treatment. And I was chuffed after learning so much about the engineering that goes into a Four Wheel Camper.

Postscript. It's always fun to wander around the back wall of the FWC factory:

A custom Four Wheel Camper on a turbodiesel Mitsubishi Fuso chassis.

Hilux turbodiesel. 'Nuff said.

Automatically better?

What does this . . .

I thought about automotive transmissions the other day while riding my bicycle.

The reason for this sideways thought process was deceptively simple: I recently restored a Sekai 2500 Grandtour road bike I bought new in 1977, complete with a ten-speed drivetrain and simple friction downtube shifters.

For the last couple of decades I’d become used to various styles of index shifting on bicycles (not to mention ever-increasing numbers of gears ad absurdum). Just click the lever or twist the grip and bang—instant up or down-shifts and a perfectly aligned chain. So pervasive and advanced has this technology become that racers and pseudo-racers now use electric shifting, the entire process delivered by a battery-powered servo. Can a fully automatic bicycle transmission be far behind?

I expected it would take a few days to re-acquaint myself with the subtleties of friction shifting: moving the lever just enough to coax the chain into catching the adjacent cog or chainring without jumping past it, then micro-adjusting to ensure a straight chainline—all by feel and ear so as not to take one’s eyes off the road. Instead, I found the instincts came back within hours—along with the sheer simple joy of operating with the bicycle, instead of just operating it. So easily did I re-attune myself to the feel of the shifter and the perfect pitch of a chain in harmony with its gears that I found myself wondering if the whole index-shifting concept was a marketing solution to a problem that never existed.

An ongoing furor in the Porsche community then jumped into my head. The company recently introduced its new GT3—long considered the ultimate driver’s Porsche with its potent naturally aspirated engine, rear-wheel drive, and numerous weight-reduction features. The new GT3, however, is available only with Porsche’s Doppellkuplung (PDK) dual-clutch transmission, which—to the horror of thousands of Porsche purists—has no clutch pedal. The driver can shift “manually” using paddles on the steering wheel, but the rest of the process is enabled by sophisticated servos and computers. The short-form response of Porsche engineers to the howls of outrage was to shrug their shoulders and say, “PDK is three seconds quicker around the Nürburgring.” End of argument as far as a Porsche engineer is concerned—why would anyone deliberately choose a slower car?

. . . have to do with this . . .

Why indeed? A response from a long-time owner summed it up. I’ll paraphrase without quotes: With current technology and some that is just over the horizon, it will shortly be possible to build a car that could drive itself around the Nürburgring faster than its owner ever could. He simply straps in, taps “Nürburgring hot lap” on the nav screen, and wham—the car rips off a 7:05 while he sits with his arms crossed or sends a live iPhone video of his “accomplishment” to his buddies.

Would such a fearsome capability satisfy a sports-car aficionado? Doubtful. Surely, even with PDK it takes an expert driver to exploit a GT3 to the fullest, and Porsche has made its awesome capabilities more accessible with automated shifts measured in microseconds. But the purists correctly point out that in doing so, something of the connection between driver and car—to use my bicycle analogy, operating with the car instead of just operating it—has been lost.

And that brings me to modern four-wheel-drive vehicles equipped with automatic transmissions.

Just a few years ago there were valid arguments to be made for manual transmissions versus automatics in terms of the vehicle’s capability. The most salient advantage of the manual became apparent when descending a very steep incline, when, in first gear/low range, engine braking would allow one to stay off the brake pedal in most circumstances, thus reducing the chances of locking up the rear tires and losing directional stability. The slip inherent in automatic transmissions rendered engine braking much less effective.

That all changed when manufacturers exploited their vehicles’ anti-lock braking sensors to introduce hill-descent control. Now the vehicle’s computer senses speed and wheel slip on a steep descent, and can apply the brakes on individual wheels as needed—something a driver cannot do. I used to think my FJ40—with a long-stroke six that produced loads of engine braking, plus the extra-low first gear in its H41 manual transmission—was adept at descents. But an LR4 or Jeep JK—any number of modern trucks, in fact—with an automatic and hill-descent control is far superior. Add to that the demonstrable superiority of an automatic on low-speed technical terrain or steep ascents (no chance of killing the engine), and the choice between transmissions becomes an easy one (although the manual still holds an edge in fuel economy—for now).

. . . or this . . .

Still, we’re back to our original conundrum. When I negotiate a difficult section of trail in the FJ40, there’s a genuine sense of accomplishment at having done it with a manual transmission and no traction control of any kind. The same section in a Rubicon Unlimited, with an auto box, lockers front and rear, and disconnecting front sway bar, is a doddle. In a 4Runner Trail, with the addition of Crawl Control, which maintains a preset speed, my input is pretty much reduced to . . . steering. Yes, if I don’t steer the right way I can still put the vehicle on its roof (as can that GT3 driver with PDK), but it’s easier to avoid doing so without the need to multitask.

Does this mean I’m against these modern developments? Not a bit of it. For one thing, I’m willing to tackle obstacles in a Rubicon I wouldn’t in the 40. And I never fail to be astonished at the combination of luxury and capability in an LR4.

Nevertheless, I’m happy to have learned my four-wheel-drive skills when knowing how to operate three pedals at once with two feet was necessary—and satisfying. I’m sure many GT3 drivers feel exactly the same way.

. . . or this?

Update: My thoughts on bicycle gearing prompted this response from Tom Sheppard, who in between solo jaunts in the Sahara is a keen mountain biker. Fair comment, Tom:

J: Re your nostalgic thoughts on bicycle gear changing, I couldn't have done it your way on my farm-track ride to the gym this morning. I definitely needed both hands on the handle bars. Attached a recent test of the Image Stabilisation on the new lens - on the limit here! I 'd have been happier with two hands here too.

From Ethiopia to Arizona—two travelers meet again

The Overland Expo has developed a reputation for bringing people together—both those making new friends and those reuniting with old ones. However, few such stories we’ve heard match this one from Mario Donovan, of AT Overland, who ran into an acquaintance at the 2014 Overland Expo WEST he last met 40 years previously . . . and 8,000 miles away.

"I was a teenager growing up in Ethiopia in the 1970s. At the time my mother worked for the Ethiopian Ministry of Tourism as a publication consultant. Many a traveler, hitchhiker and overlander came through her office, and sometimes they’d end up crashing on the floor of our apartment. I was maybe fourteen or fifteen at the time, and at the height of adolescent reverie. I lusted over motorcycles every waking moment, even more than girls.

I remember my mom introducing me to a British fellow who was on hiatus from his journalism job so he could ride around the world on his motorcycle and write about it. It was a super cool bike because it was a twin, not a single-cylinder as most of the bikes were there. What a dream of independence and freedom for a young man. At the time I was still without my driver’s license, but learning how to pop wheelies on my friend’s bike, and occasionally hot-wiring my neighbor’s bike when he was out of town.

Although I only met the British rider briefly, I thought he was stud for doing what he was doing. Then, maybe five years ago, I read Ted Simon’s book Jupiter’s Travels, and when I got to the short section about his time in Ethiopia it hit me: That was the guy! Not much of a story but a happy coincidence—the Kevin Bacon thing. When I shared it with Ted he seemed rather moved by it, and I was honored to have met him again nearly 40 years later—and to share a drink with him no less!"

Accessible wonders

Many years ago, while on an assignment for Outside magazine, I was graced with the incomparable experience of viewing Victoria Falls for the first time by walking up to the edge of the drop on Livingstone Island, right in the middle of the mile-wide cascade, after arriving by canoe, just as David Livingstone had almost exactly 150 years before. The breath literally left me; I gasped and very nearly wept at the sight. Only the terror of totally losing my cool in front of my guide kept me halfway composed.

Much more recently—last week in fact—I was graced with another first: driving out of the tunnel on California State Highway 41, the Wawona Road, and seeing Yosemite Valley spread out before me below sweeping clouds and mist. El Capitan rose on the left in an impossible vertical wall; Bridalveil Fall plunged in a gossamer thread on the right.

To paraphrase: The breath literally left me; I gasped and very nearly wept at the sight. Only the terror of totally losing my cool in front of my wife kept me halfway composed.

It was a good lesson in something many of us tend to forget: You don’t necessarily need to travel to Zambia (or fill in the blank) to have a once-in-a-lifetime experience. We were two easy day’s drive from home, and the sum total of our off-pavement excursions to that point had been about 500 yards of dirt road to reach a Forest Service dispersed campsite. Yet that view of Yosemite Valley will forever live in my memory directly alongside that first vertiginous peek over Victoria Falls.

The two natural wonders share more than you might think. Both were “discovered”—i.e. sighted for the first time by a person of European stock—in the mid-1800s, after of course being well-known to the locals for ages. In both cases, the “discoverers” were on profit-driven missions: Joseph Walker was looking for furs when he stumbled on Yosemite Valley, and Livingstone hoped to find a water route into the heart of the African continent. Both sites are now overrun with tourists pursuing, at times, tangent activities that seem utterly superfluous to me: I’ve said frequently that if you view Victoria Falls for the first time and think, Okay, cool—now I need to go bungee jumping off the bridge, then there’s something seriously wrong with your sense of wonder.

Yet the grandeur of both places effortlessly transcends the swarms of humans buzzing around them. Even at Yosemite, we found a trail along the Merced River, under El Capitan, on which in four miles we met two other people. And at Victoria Falls I spent a night camped on Livingstone Island (alone except for an askari), and got up at midnight to see the “moonbow”—a rainbow caused by moonlight shining through the mist of the falling water. Later I was awakened by the sound of foraging elephants, which wade to the island at night to feed.

So maybe I shouldn’t complain that everyone else was off bungee jumping.

The author, alone at dusk on Livingstone Island. The bungee jumpers are off toasting their adventure somewhere.

The author, alone at dusk on Livingstone Island. The bungee jumpers are off toasting their adventure somewhere.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.