Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

A challenge to winch bumper manufacturers

Once upon a time, adding a winch to an overland vehicle was easy. Series 2 and 3 Land Rovers, 40-Series Land Cruisers, and Jeeps were built with chassis rails that extended a good foot in front of the radiator, fronted by a solid steel bumper. To mount a winch you basically plopped it there, bolted it down, and hooked up either a PTO driveshaft or wiring. Done. Even the bulky Warn 8274 on my FJ40 was an easy installation.

It’s different these days. With scant few exceptions, those protruding steel bumpers have been sacrificed in the (commendable) search for aerodynamics—i.e. fuel economy—and safety, via computer-designed crush zones and air bags. Give me a choice of being in the 40 or our Tacoma in a head-on collision and there’s no doubt which I’d choose.

But if you want to install a winch on these new vehicles, you need to replace the 10-pound body-colored plastic facade that looks like a bumper with a dedicated steel or aluminum structure properly connected to the chassis of the truck, and capable of absorbing several tons of force. Thankfully, numerous companies have risen to the challenge, especially for the more popular models of pickup and SUV.

However—I seem to be noticing a trend in aftermarket winch bumpers that is vaguely unsettling: a trend toward fashion over function. That 8274 on my FJ40 is right out in the open—I can see it operating, I can watch to make sure the line is spooling correctly, and if it isn’t I can stop the procedure and fix it. One of the requirements to pass the winching section in the N.P.T.C. Certificate of Competence in 4WD is, “Ensure the winch components are in suitable condition.” Another is, “Ensure the winch is free from obstruction and the line is spooled properly.” Both are easy to confirm with that 8274.

With an increasing number of modern winch bumpers, either is virtually impossible. The only view of either the winch or the drum and line is a peek through the fairlead. A tiny hole gives you access to the engagement lever. Recently I was respooling line on a student’s winch and had to have him shine a flashlight through the fairlead while I crouched in front of it and peered inside so I could ensure the line was going in correctly. Had there been a bad snarl we would literally have had to remove the bumper to fix it.

Anther vital winch-bumper component is either shrinking or going away altogether—recovery points capable of and suitable for attaching a shackle. Properly, a shackle eye should be nearly as thick as the width of the jaw on a shackle, to prevent twisting and off-angle stresses. Lately I’m seeing them much narrower—or simply missing, so that there is no provided way to rig a double-line pull from your winch to an anchor point and back to your bumper, or to safely secure a friend’s winch line to your vehicle.

Several months ago I spoke to a rep from a major bumper manufacturer (I’m not going to name names in this piece because I’m not discussing quality, which is uniformly high in this segment; I’m discussing choices made by the manufacturer and consumer). The rep said that recovery points had been eliminated on his company’s bumpers due to airbag compatibility issues. I’m . . . not sure about this. It’s my understanding that airbags are triggered by accelerometers, which detect deceleration consistent with that of a collision severe enough to warrant deployment, and then send a trigger signal to the device. Often these accelerometers are positioned in the cab of the vehicle, nowhere near the bumper. In any case, if you make a bumper capable of withstanding several tons of pull provided by the winch mounted on it without affecting airbag deployment, I can’t understand why adding recovery points capable of withstanding several tons of pull would suddenly compromise the system. (Note that I did not say it can’t be so; I simply said I don’t understand how it could be so.)

One source I spoke to told me that the only thing separating airbag-compliant winch bumpers from non-airbag-compliant winch bumpers is that the maker of the latter did not spend the huge amount of money necessary to actually conduct crash tests to prove unequivocally that the vehicle’s airbag will still deploy with the bumper mounted. In researching various crash reports I have yet to come across a case in which it was proven that an aftermarket bumper prevented an airbag from deploying (if anyone reading this has such documentation I’d be grateful to hear about it).

The only potential effect of a winch bumper on airbag deployment that I know of is the risk of triggering in a collision that occurs at a lower speed than that at which the accelerometer would normally trigger the device. Some vehicles are built with crush cans behind the stock bumper, designed to absorb the energy in a minor collision without setting off the airbag. An aftermarket bumper that eliminated these crush cans and tied directly to the frame could potentially fool the carefully calibrated sensors into “thinking” that the crash was worse than it actually was. This would certainly be an alarming (and probably expensive) surprise, but one unlikely to cause serious injury.

I’d like to see—within the boundaries of passenger protection in a collision, of course—a return to winch bumpers that optimize access and safety for the winch operator. Winching is an activity fraught with potential risks at the best of times; deliberately making it difficult or impossible to ensure the winch is operating correctly is a big mistake. At the very least, a bumper should be equipped with a removable access port that allows full-width access to the drum and line. And the bumper needs to be equipped with proper recovery points that will adequately support a shackle—either that or the manufacturer could offer separate, frame-mounted recovery points.

There’s nothing wrong with fashion, as long as it does not compromise function. The best functional designs make their own fashion—what can be better looking than something that works perfectly?

My ride for the next week . . .

Five-liter DOHC V8, variable turbo, 310 hp, 555 lb ft.

Full review will appear in OutdoorX4.

Buy the tire you need, not the one you want

Recently I received a set of the all-new Yokohama Geolandar AT GO15 tires to review for OutdoorX4 magazine. While sold as an “all terrain” tire, the tread on this Geolandar looks mild compared to many similarly marketed tires. And that got me to thinking about overlanders and our tire choices.

It’s natural to gravitate toward an aggressive tread design when buying tires for a four-wheel-drive vehicle. A more aggressive tread means better traction in steep or loose terrain, right?—which is why we have four wheel drive in the first place, right? And besides—let’s be honest—a mud-terrain tire just looks cooler than a more street-oriented “AT” tire. If appearance has never, ever entered into your tire-buying decision you’re a more logical thinker than I am.

Obviously, however, there are logical aspects to tire selection besides traction. The most critical of these—in fact the most critical of all— is safety. A street-biased tire with more closely spaced, shallower tread blocks will exhibit significantly better grip for both handling and braking than one with hyper-aggressive, open-blocked tread. That aspect could quite literally be a lifesaver in the right (wrong) scenario.

Fuel economy is a factor as well. When I switched from BFG All-Terrains to BFG Mud-Terrains on my FJ40 (partially because, yep, they just looked better) my fuel economy dropped by almost exactly one mile per gallon—and one mile per gallon on an FJ40 makes a difference, let me tell you. Then there’s tread life. Those closer tread blocks translate to less squirm, which translates to longer tread life given the same compound. Finally, even with modern computer-designed tread, aggressive tires tend to be louder at high speed, which can be a fatigue factor on long drives.

All these advantages to street-biased tires are obviously mostly advantageous on the street, and that’s where logic butts up against romance. Most of like to think we spend more time off pavement than we actually do. The reality is, if more than ten percent of the miles you put on your overland vehicle are actually off pavement, you are quite an adventurer. I’m not sure Roseann and I hit that, and we cover seven miles of dirt road just to reach our house. Much more frequently a backcountry journey will entail several hundred miles of highway and maybe 40 or 50 miles of trails. Thus, for most of us, for most of our time behind the wheel we would enjoy better handling, braking, fuel economy, and tread life with a less-aggressive tire choice. And we wouldn’t have to crank up the sound system so much to count how many times Terry Gross says “like” or “um” in one interview. Sorry, personal gripe.

Where was I? Right: There’s an additional factor to consider for those of us who own modern vehicles with sophisticated ABS-based traction systems and hill-descent control: We have more and better inherent traction available to us than we did when driving older vehicles with simple part-time four-wheel-drive systems. So we can enjoy just as much off-pavement ability with a less-aggressive tire—as anyone can confirm who’s watched Land Rover’s LR4s on street tires negotiate the Overland Expo driving course.

So the next time you buy tires for your overland vehicle, consider carefully—and logically. Do you really need those BFG Mud-Terrains, or would the All-Terrains perform better most of the time? For that matter, would BFG’s Rugged Trail suit your needs? Get the tire that works best, not the one that looks best. Then you can smile condescendingly at the guy driving by in the jacked up truck riding on those howling Super Swampers.

2015 Continental Divide vehicle report

Last year, the 1600 miles of the RawHyde/Exploring Overland Continental Divide trip proved to be a challenge for the participating vehicles (report here). This year’s journey proved just as challenging, in different ways. In no particular order the nine vehicles along this time were:

- 2008 Ford F350 6.4 diesel double-cab pickup

- 2012 Toyota Tacoma 4.0 V6 with Four Wheel Camper (our JATAC)

- 2010 Toyota Tacoma double-cab 4.0 V6 supercharged, with canvas bed shell

- 2014 Ram Power Wagon double-cab with Four Wheel Camper

- Ford Raptor with Four Wheel Camper

- 2014 Ford Raptor with Northstar camper

- 2009 Sportsmobile on a Ford 6.0 diesel chassis

- Toyota Tundra with fiberglass shell and roof tent

- 2008 Toyota Land Cruiser 200-Series with roof tent

For the first couple of days we seemed to be getting off lightly—the worst issue to surface was a burned out turn signal bulb in the aftermarket headlamp assembly on Ross Blair’s Tacoma. But somewhere north of Grants, New Mexico, Michael and Darla’s Raptor/FWC combination blew the Firestone air bag on the right rear spring on a long off-pavement section, causing the bag’s internal bump stops to slam against each other over the mildest terrain. Inspection revealed that the air bag was the longer of the two offered for the Raptor by Firestone—probably a mistake with a camper mounted. It appeared that repeated stressing of the bag being folded over the lower location cone caused the hole—a worrying failure given the mere days-old installation. Much worse was the unbelievably shoddy installation by Desert Rat Off Road Center in Tucson. The over-long U-bolts securing the lower brackets had been left untrimmed, so they impacted the spring perches when the suspension flexed, bending them and smashing the upper threads. Phil Westergren, our ace group mechanic, advised Michael that the best approach might be to simply remove both bags and let the truck sag; when Phil did so, he found the nuts on both U-bolts finger tight. Disappointing.

With both bags removed, the compliant Raptor suspension did droop noticeably, but retained far more travel than had been available with the collapsed bag left in place, so Michael and Darla were able to continue along with us. (Interestingly, Dennis and Margie, also in a Raptor with a heavier Northstar camper, had the same bags and had no issues the entire trip.)

Day four brought us to a fairly challenging boulder-strewn uphill section on a Forest Service road. I climbed in the passenger seat of the Sportsmobile to offer Marka some in-cab hints on wheel placement, but it soon became apparent the vehicle was suffering a distinct lack of traction, as she failed to climb several off-camber sections. Indeed, Phil, who was marshalling, reported that the front wheels were not getting power even though the (manual) hubs were locked, the driveshaft was turning, and as far as I could determine from inside the Atlas transfer case was correctly engaged. Fortunately the Sportsmobile had an automatic rear locker—and thus full traction to both rear wheels—so we were able to get Marka through the difficult section. But it presaged more significant problems on the icy and muddy sections we knew would be ahead. This was another issue we had no time to investigate thoroughly on the trail—the constraints of a paid trip.

After camping next to Elk Creek (Colorado), we attempted to drive up over Elwood Pass. However, we began encountering snow patches even lower than last year, and soon Phil decisively stuffed his F350 into a three-foot-deep bank completely covering the roadway, halting his and our further progress. With a quick KERR tug from Ross’s Tacoma (eliciting the expected comments from the Toyota drivers), we bailed and headed for Salida, the town beneath the 10,000-foot grass plateau on which the RawHyde Colorado camp sits.

Marshaling a kinetic recovery from a safe distance.

Reports indicated that, despite recent snowfall and rain, the back dirt route was clear, so we headed up the road through the San Isabel National Forest. As usual, Roseann and I took the tailgunner position to keep an eye out for any BF-109s tracking us with their MG 17s. No, wait, that’s not right. In this case, “tailgunner” just means making sure no one gets lost.

For ten miles or so the climb was uneventful—there were a few areas of slick mud and flowing ditches on the side, but nothing challenging—we were continually hitting lucky weather windows on this trip.

Then, after an easy creek crossing that led to a slight uphill section where water cut across the road and a ditch on the right carried it off, the two-meter crackled, and Cheryl in the Power Wagon said, “Um, I think I’m stuck,” to which Ross immediately replied, “No, you are definitely, absolutely stuck.” She had taken too low a line to cross the water-filled ruts in the road, and the massive truck with its mounted camper had slid into the ditch.

First try at towing, which would fail decisively.

The axiomatic approach in such situations is to begin recovery with the simplest technique, then work upwards in complexity and potential risk. A simple pull from Phil and his F350 had zero effect, so I replaced Cheryl in the driver’s seat and we rigged a kinetic rope between the trucks. Phil gave me some slack, backed up smartly but not quickly—and the truck moved.

For about 15 feet. I was trying to turn it out of the ditch, but the slope sucked in the front tires and Phil’s truck spun to a halt—not helped by me staying on the Ram’s throttle for just a second too long, further burying the right rear tire in the muck if it needed further burying.

Time for the winch, but first Roseann left to drive ahead with the rest of the group to the RawHyde camp, while Phil, Ross, Kevan, and I stayed (along with the apologetic Herndons). Before the group left, we collected four MaxTrax-style recovery mats and I got our recovery kit out of the Tacoma. It was getting late and we did not want any more false starts, so we went back to square one, got out the shovels, and cleared muck until we could get a plastic recovery mat wedged under the front of each tire. The Ram was equipped with an excellent and powerful Warn 16.5 winch, but I wanted to both maximize its efficiency and slow down the operation, so we attached a pulley block to the F350’s front bumper and led the cable through it and back to the Ram.

First try, with rocks stacked in front of the Ford’s tires and brakes full on, the winch inexorably pulled the anchor truck toward the stuck one. The road surface was just too slick with mud to provide traction. So we daisy-chained Ross’s Tacoma behind the Ford, added more rocks, and that, finally, did the trick: The Ram ever so slowly hauled its way diagonally out of the ditch and on to ‘firm’ ground. We got to camp just in time for one of trip chef Julia’s superb dinners.

Ross Blair's Tacoma against the Colorado skyline.

After a layover day (and a timely winching seminar) at the RawHyde camp, we headed north to Hartsel for fuel, then explored several back roads on the way to Steamboat. At the fuel stop it became clear the Ram was leaking significant oil from the front main seal. Since it was highly unlikely this had been precipitated by the bog and recovery it had to be chalked up to coincidence. The engine only had 80,000 miles on it, so this seemed a bit premature. Near the same time, Joe noticed a heavy oil drip from the 6.0 turbodiesel in his Sportsmobile. This truck was equipped with dual external Amsoil filters—a worthy upgrade, except that one of the O-rings in the frame-mounted assembly had failed. Adding complexity also adds potential failure points.

Pushing a proper bow wave on a stream crossing.

From Steamboat we faced what would turn out to be our most challenging day—a circuitous, almost all off-pavement drive north along Elk River Road, past the comically oversized ‘lodge’ at Three Forks Ranch—at $850 per person per night out of our range—and into Wyoming. Since major highways in Wyoming are often barricaded during bad weather (“If light is flashing, Wyoming is closed—Please return to Colorado”), the side roads can prove adventurous. And Sage Creek Road turned out to be just that—40 miles of oil-slick mud that reminded me of, well, the camping area at the 2015 Overland Expo, actually. Joe in the temporarily two-wheel-drive Sportsmobile had the most difficult task: While the automatic rear diff lock gave him nearly as much traction going uphill as the open-diff four-wheel-drive vehicles had, when you lose traction on a diff-locked axle, you lose it all. Yet he only lost it on one muddy dip, sliding gracefully sideways into the shoulder. Once Joe realized he was stuck he instantly cut the power (er, quicker, in fact, than I had in the Ram), thus we were able to hook up a strap from David and Noell’s Land Cruiser and tug the Sportsmobile free easily. For the rest of the path to Rawlins we watched from the rear as Toyotas, Fords, and the lone Ram waggled up inclines and crept cautiously down greasy slopes. It was an impressive display of driving by everyone.

David Alley prepares to gently tug the Sportsmobile out of a ditch.

Sadly, by the time we reached Wyoming’s Red Desert in the Continental Divide Basin, the Sportsmobile’s turbodiesel had developed a misfire—possibly an injector issue—and this, combined with the oil leak, convinced Joe and Marka to leave the group a day early and head for Salt Lake City to address things. The rest of us enjoyed a last camp on a broad grassy slope next to a creek, and watched a near-full moon pace the stars overhead across a sky unsullied by the lights of civilization.

Conclusions? Note that several of the issues we experienced were caused by aftermarket additions—air bags, external oil filters. That’s a good reminder to be extremely careful when considering such modifications, to make sure any you choose are of high quality, and to be damn sure the installation is done correctly. It also points out the importance of pre-trip maintenance and inspection: The Sportsmobile, for example, had gone over 10,000 miles since its last oil change, an interval endorsed and boasted about by Amsoil, but over-optimistic for this kind of hard use.

Ford Raptor + no mudflaps =

A dual-band radio for the JATAC

If you do any overlanding with a group, especially in remote areas and on routes where the vehicles might be out of sight of each other for periods, it’s smart to have some means of intra-group communication. Cell phones are okay for person-to-person talking, but cell coverage is still far from universal (more so where many of us like to explore), and in any case a phone is worthless for broadcasting a quick message to multiple vehicles at once. For that you need a radio.

Handheld UHF (Ultra High Frequency) FRS (Family Radio Service) transceivers are okay for very short-range work, as are the CB (Citizen’s Band) radios made famous by the 55mph speed limit, Smokey and the Bandit, and several bad country songs. But if you want some real range you’ll need to go the pro route and install a two-meter transceiver.

Two-meter communication uses the 144 to 148 MHz band of the spectrum. Due to the frequency allocation, and the power allowed to the units, range is significantly greater than possible with FRS or CB units—and it can be extended even farther by using repeaters. You need an FCC Technician Class amateur radio license to operate a two-meter radio, but the test is easy to pass after a review of the associated technology and rules available several places online, such as here. I’ll never live down my test, when I missed one question out of 35 while Roseann at the next desk aced hers. I should have cheated. (If you are attending the Overland Expo, you can study on your own, then pay the nominal fee and take the test at the Expo on Sunday between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m.)

For some reason I kept putting off installing a two-meter radio in the JATAC—we used a handheld throughout the entire Continental Divide trip last year, which is pretty lame for the trip leaders. So I rectified the situation for this year’s upcoming CD journey.

On the advice of ham-radio guru Bob McNamara (a frequent instructor at the Overland Expo), I ordered a Yaesu FT-8800R/E dual-band transceiver. Operating either in the two-meter or 70cm bands, the FT-8800R/E can put out 50 watts of transmitting power on the former (compared to five for most handhelds), and has a bunch of additional features that will take me years to master. If you’re faced with a difficult installation scenario (common in modern trucks with crowded dashes and even more crowded wiring harnesses behind them), the faceplate can be mounted on its own, connected to the remotely positioned main module with an included cord. It turned out in our case (2012 Tacoma), that a pocket in the center console just in front of the (manual transmission) gear shift seemed almost deep enough for the entire unit. I needed to pull everything out to determine if that was the case.

Modern truck interiors are a bit of a jigsaw puzzle. Taking one apart can be an hours-long struggle or—if you know the sequence—a matter of minutes. A call to our friend and master Toyota mechanic Bill Lee (who, annoyingly, keeps moving farther and farther away—first 250 miles, now 400 and counting*), and I had the secret to the center console. The cup holder assembly is held in by clips; pop it straight up and a couple of bolts and screws underneath release the rest of the assembly.

I cut a hole in the back of the pocket large enough to accept the back of the radio and allow access to the power cord, antenna, and remote speaker jack. However, a trial fit revealed something else in the way: a large, bolstered plastic tab extending vertically downward from the dash structure itself. Even Bill had no clue as to its function. Its position directly above the air bag computer implied a relationship—some sort of protection? In any case it was barely but indubitably in the way of the antenna jack, so I unceremoniously took a hacksaw blade to it and cut off just enought to create a path for the antenna cable. Wit that accomplished, another trial showed the radio to sit nicely, clear of all movements of the shift lever.

Note the grey mystery tab on the right. Relieving a notch out of the left side allowed clearance for the antenna lead.

I’d bought a quick-release bracket for the radio; removing the console and loosening a few bolts on the bottom dash section gave me barely enough room to get my hand in behind and above the support piece to install stainless 10/24 locknuts and washers on the bolts holding the bracket. Amusingly, the perfect tool to drill the holes for those bolts through the plastic, with little maneuvering room, proved to be the awl attachment on my Swiss Army knife.

With the radio in place, it was time to run the positive and negative leads of the power wires through the firewall. In my old FJ40 such a task is easy: Find a blank spot on the steel firewall, drill a hole, run the wires through it and shove in a rubber grommet. Done. Today’s trucks are different. There are multiple layers of plastic, carpet, and soundproofing to get through—and masses of wiring to avoid—before you even reach the firewall. Fortunately, on the driver’s side of the Tacoma is a very large rubber seal through which a bunch of wiring connects the engine and battery to the dash. I found a phillips screwdriver with a long shaft, taped the end of each radio lead to it, and poked through the seal into the engine compartment. The Yaesu positive and negative leads are each equipped with inline fuse holder, and I wanted to be able to use the radio even with everything else in the truck turned off, so I ran the leads directly to the battery. (This is a good idea anyway, as a transceiver requires full voltage to function properly, and wiring from the vehicle's fuse box can introduce spurious electrical noise. The FT-8800 has an adjustable auto shut-down function to prevent draining the battery.)

For the antenna lead I found an existing hole in the passenger footwell, up behind the vent fan assembly. After removing the rubber plug in it, I had to file a slot in the hole to get the antenna lead through it, but it went through easily afterwards with the glove box assembly removed for access.

I had several options for mounting the antenna, but decided on a hood lip mount—a Comet RS-840 with a PL-259 connector—and a Comet CSB-750A dual-band antenna. The mount adjusts to enable a vertical stance for the antenna—I can’t stand tilted antennas—and in addition to clamping to the lip of the hood with four hex-head screws, has a brace that extends to the fender to enhance rigidity. On our truck the brace didn’t rest against the fender lip, resulting in an obnoxious side-to-side wobble in the antenna, so I glued a thin piece of rubber to it. That made a solid connection. Once mounted thusly, you don’t want to close the hood as so many people do, by dropping it from a foot or so high. Since I’ve always loathed this habit, and instead close all hoods by lowering them gently over the safety latch, then pushing down, this is not an issue for me.

One other note here: The antenna needs to ground to the hood via the four hex-head clamping screws. On the Tacoma hood, the edge underneath is trimmed with a thin strip of rubber, so you need to be sure the screws get through the rubber to the bares steel. I used a very small flat-head screwdriver to twist through the rubber strip.

And . . . finished, aside from mounting the microphone holder to the side of the transmission tunnel, and ordering a Yaesu external speaker. At last we’ll have a radio suitable for our responsibilities as trip leaders, and great for simply sharing interesting sights along the spine of North America and elsewhere.

*If you own a Toyota or Lexus and live within, say, 400 miles of Farmington, New Mexico, Bill's Toy Shop is worth the trip for major work. He'll also be teaching several mechanics classes at the Overland Expo. billstoyshop.com

Now it can be told . . .

Bear with me for a bit? Sometime in the early 1980s I happened across an intriguing article in a U.S. four-wheel-drive magazine. In it was a photo of a fellow standing in a sandy expanse of desert, next to a very early Range Rover. A line bisected two words scrawled in the sand: ‘Mali’ and ‘Algeria.’ The fellow leaned on a shovel, apparently the tool used to scribe this middle-of-nowhere border.

That was my introduction to Tom Sheppard, ex-Royal Air Force test pilot and the leader of the first west-to-east crossing of the Sahara Desert, the Joint Services Expedition, in 1975. In the years to come I followed his (frequently solo) excursions through the most isolated regions of the Algerian Sahara, often completely off-tracks. In 1999, when I heard he had published a book called Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide that would be available at Land Rover dealers, I drove 120 miles to the swank showroom in Scottsdale, and stood in line to pay for a copy behind wealthy urbanite Range Rover buyers picking out Africa-themed spare tire covers.

Fast forward eight or nine years, when I was fortunate enough to work with Tom during my time as editor of Overland Journal. A year or so later, Roseann and I had the opportunity to meet him on a trip to England. To my amazement, there was not a trace of the ex-test-pilot-Sahara-explorer-RGS-medal-winner arrogance I would have expected. Instead, we were welcomed by a quiet, humorous, and steadfastly self-effacing man who doted on the horses and sheep that grazed on the farmland adjacent to his modest cottage. Over the next few visits we became friends.

Fast forward again to 2014. We’d been trying to convice Tom to publish a fourth edition of VDEG (‘veedeg,’ as he and everyone refers to Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide). The third edition had sold out in half the time he expected. He agreed it was needed—but then sent me a mockup of the proposed cover, which (as you can see from the header image) was a complete shock.

So now, after seven months of exhaustive research and writing on both Tom’s and my part, I can announce that the fourth edition of Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide, by Tom Sheppard and Jonathan Hanson (woo hoo!) will be out in mid-May, with copies also available at the Overland Expo. This edition has received the most extensive updating and expanding since the original, with much more content specifically relevant to North American readers than in previous editions. Total content is up by nearly 20 percent—it's now a 600-page book.

Any verbose attempt on my part to explain what an honor this is would be futile. So I’ll just say I’m thrilled and humbled to have contributed in a very minor way to a classic in the field of expedition literature. If you don’t yet own a copy of VDEG, or if you have previous editions and need to complete your collection, please follow this link and put your name on the waiting list. As before, VDEG 4 will be produced by Tom’s one-man publishing enterprise, Desert Winds, and quantities will be limited.

JATAC update: After a near-death experience

One afternoon early last year I was driving the JATAC, our Tacoma/Four Wheel Camper combination, west on Arizona’s Highway 86—a two-lane, 65mph road flanked with emergency lanes. As I approached a side road coming in from the north, I saw a Subaru sedan waiting at the stop to turn east, across my lane. Meanwhile, an SUV in front of me put on its signal and pulled into the turn lane to turn north. As I passed the SUV, the driver of the Subaru, who had apparently missed seeing the white pickup and cabover camper headed his way, accelerated, pulled out in front of me—and then stopped as he saw what he’d done. This left me heading toward his door at 60mph-plus, about 50 feet away.

In one of those slowed-down time-warp instants I saw with utter clarity the driver’s face, looking at me with the open-mouthed certainty that he had just committed suicide. There was scant chance I could avoid hitting him. Braking would have been laughably futile. The only possible alternatives were the desert on the right or, across the oncoming lane, the desert on the left. I saw there was no opposing traffic, so I violently yanked the steering wheel left, clearing the front of the Subaru by what could only have been inches. On the edge of either sliding or rolling—I wasn’t sure which—I yanked the wheel the other way, corrected a violent yaw, and managed to keep the truck on the pavement in the oncoming emergency lane, where I slowed, checked traffic (the Subaru had fled—you're welcome, pal), and pulled across again to stop off the road and restart my heart.

I got out and checked the truck and camper. Everything seemed okay, so I continued home. But on the last rough dirt section I heard a faint but obvious rattle coming from the camper area. At home I investigated and found that one of the four turnbuckles securing the camper to the truck had split at the open hook. I’d been meaning to replace the stock, aluminum-bodied turnbuckles anyway, and took the opportunity to install forged steel replacements.

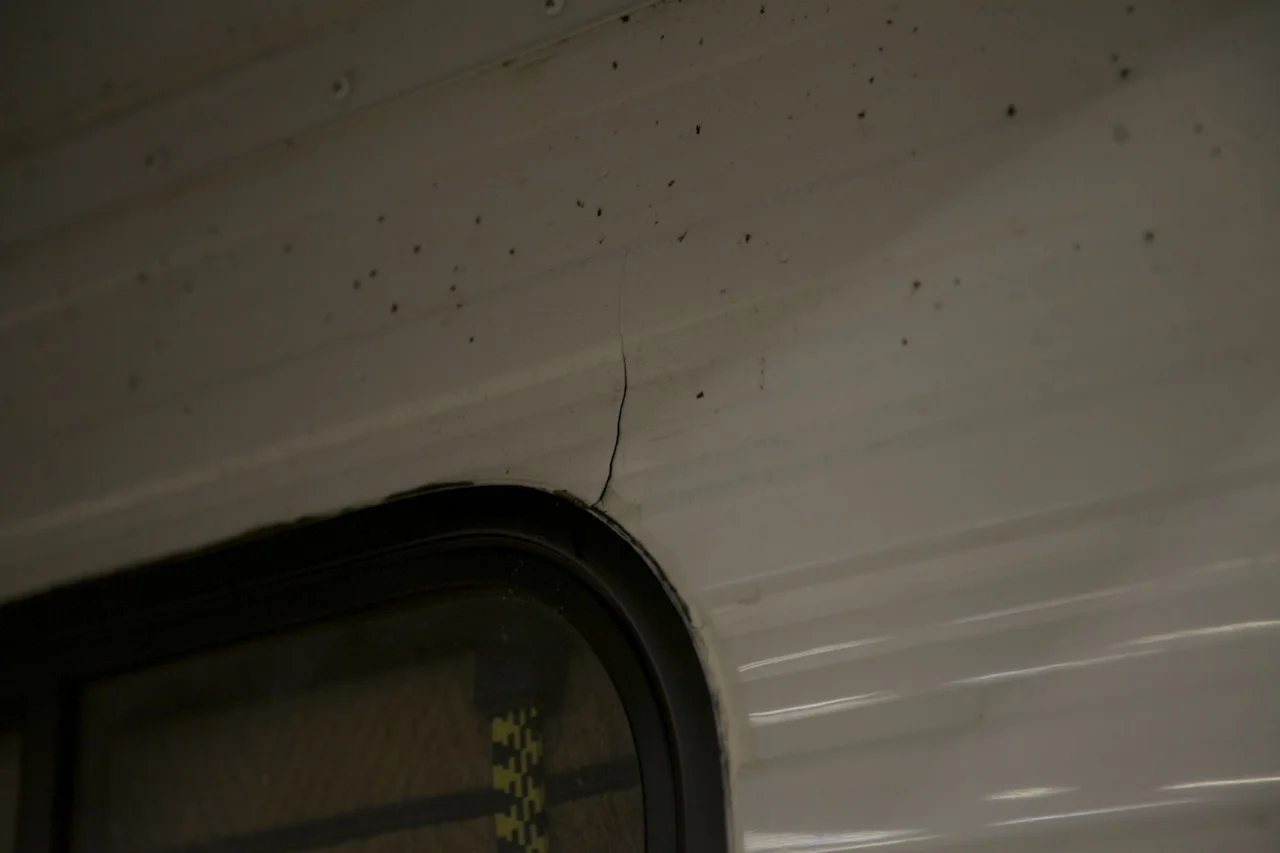

That seemed to be the end of the matter. However, several months later while washing the truck I noticed a split about two inches long in the camper’s aluminum skin, extending from the upper right corner of the front window, behind the truck’s rear window. Investigation revealed a similar split on the opposite side. Could the near miss have been the genesis of the splits? Difficult if not impossible to say, but it was a worrisome development.

I showed the splits to Tom Hanagan of FWC at Overland Expo EAST, who urged a factory visit to remove the skin and investigate the possibility of a cracked frame member or weld. So this Christmas we combined visit to see family on Coarsegold, California, with a trip to the Four Wheel Camper factory in Woodland. We took the opportunity to have a couple of upgrades done to the camper—the company is constantly evaluating current systems and components, looking for ways to improve the product.

As you can see, the splits would be easy to miss if you weren't paying attention. Between the time I noticed them and the time we got to FWC, they seemed to have remained more or less stable.

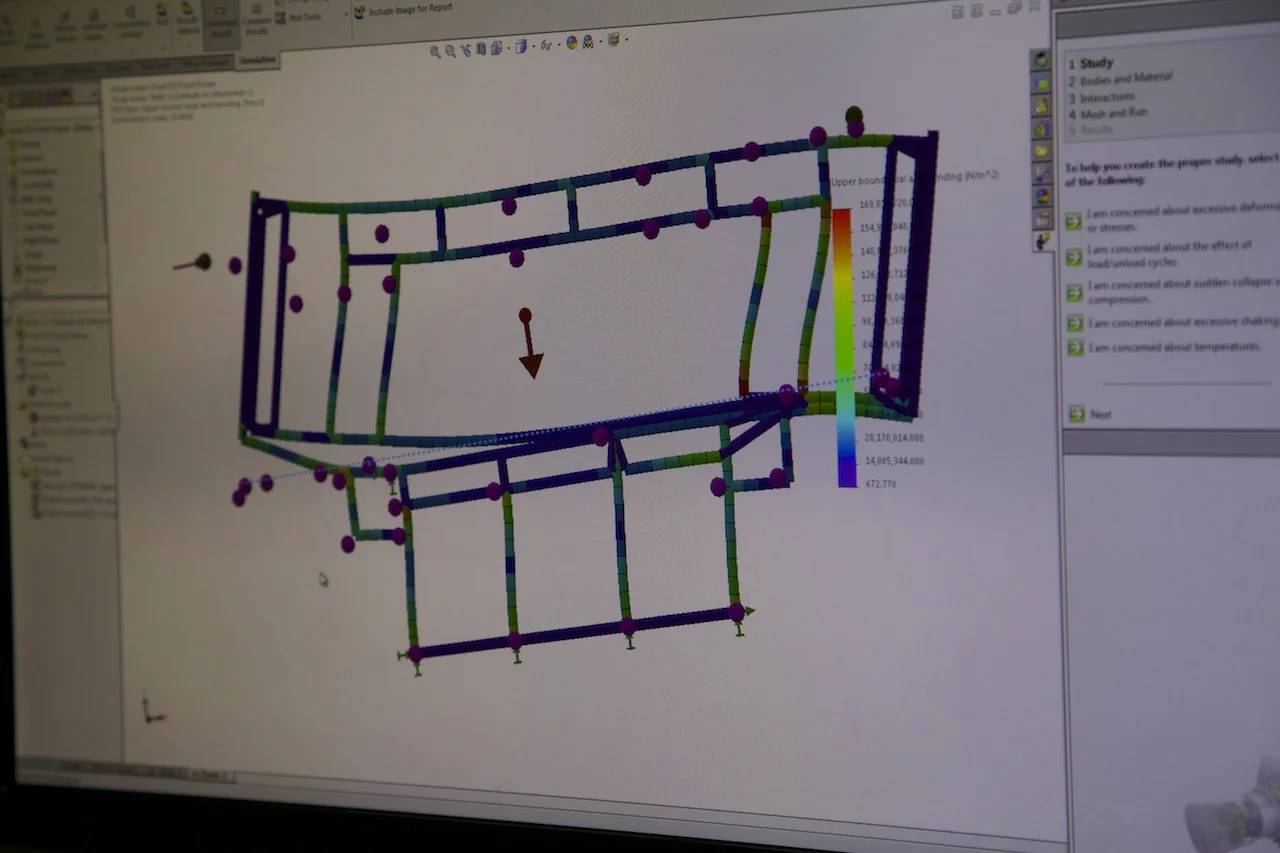

With the front skin removed, Tom Hanagan inspected the frame, but found no cracked welds or any other damage. He had only seen this issue a couple times previously, but nevertheless decided that further structural engineering might be worth investigating. So I went upstairs with Robin Pritchard, FWC's new engineer, and watched while she created a CAD image of the Four Wheel Camper's front frame structure.

Once the virtual frame was assembled on screen, Robin applied a significant simulated side load. With no other structure or skin to reinforce the isolated frame, and the distortion effect magnified hundreds of times by the program, the graphic showed that the area of highest stress occurred . . . at the top corners of the window opening.

Robin studied the image for a minute, then applied a simple boxed reinforcement on either side of the window opening with a few clicks of her mouse. Immediately the distortion was attenuated, and the angry red color that highlighted stresspoints cooled off to a benign yellow. Tom looked at the result, and rolled our camper over the the welding area of FWC's huge factory, where the fabricators welded in two channeled aluminum pieces on our frame. The entire process added perhaps six ounces to the weight of the camper.

With the reinforcements in place, Jay Bailey re-positioned the rigid foam insulation, and installed a new front skin.

Very soon the front of the camper looked new again. Despite the uncommon nature of this issue, Tom has incorporated the reinforcement into all new campers that have the forward dinette. He is also currently testing a new, forged turnbuckle that I think will be a significant improvement in the anchoring system.

Repairs completed, we had FWC install external roof-lifting struts on the front and rear of the camper. With only the single internal pair of struts, Roseann had trouble lifting the back of the roof when we set up the camper. She has no trouble with the external struts, and eliminating the internal pair cleaned up the interior appearance and added room on the bed. FWC also installed a new style table in the front dinette; with a simpler, stronger, and more elegant swivel.

Soon the camper was back on the Tacoma, looking visibly chuffed after its little spa facelift treatment. And I was chuffed after learning so much about the engineering that goes into a Four Wheel Camper.

Postscript. It's always fun to wander around the back wall of the FWC factory:

A custom Four Wheel Camper on a turbodiesel Mitsubishi Fuso chassis.

Hilux turbodiesel. 'Nuff said.

Just say no to wheel spacers . . .

( . . . and other “performance enhancements” that compromise reliability)

Every once in a while—well, quite frequently, actually—my friend and master Toyota mechanic, Bill Lee, reads something in a magazine that sets his teeth on edge, and he’ll fire off an email to me sprinkled with a lot of exclamation points. Invariably the offending passage involves a “build” article, wherein the writer has taken a perfectly functional truck and set about “improving” it. I seem to be Bill’s favorite person with whom to share his pain, perhaps because I react the same way when I read some of this stuff, which, when published nationally, thousands of readers are likely to take as gospel and imitate.

It’s not that either of us is against any modifications at all. Many accessories can add to the utility, convenience, and even safety of a four-wheel-drive vehicle without compromising reliability or durability: better tires, driving lights, winches, bumpers with proper recovery points, dual-battery systems, built-in air compressors, etc. Even some driveline and chassis modifications can be made that have few or no drawbacks. Electric locking differentials, for example, generally do not compromise the strength of the third member, and if they stop working you’re normally just back to a stock diff. Aftermarket shock absorbers frequently exceed the performance of factory units—especially if, as in our case, you’ve added a 1,000-pound camper to your truck. High-quality aftermarket springs (or, in the rear, air bags) can enhance weight-carrying ability, or improve ride.

The problems start when you begin messing with the fundamental engineering and design parameters of the truck.

Bill’s most recent email concerned a Tacoma on which the writer had installed, among other things, new, wider tires. He subsequently found that the tires rubbed the inner fender wells at full steering lock, especially when the suspension was compressed. So, rethink and install narrower tires? Nope. Instead, he installed a set of 1.25-inch wheel spacers—an inexpensive, bolt-on accessory that literally moves each wheel outward from its hub by an inch and a quarter. This, the writer reported, (mostly) solved the rubbing issue, and additionally widened the track of the truck a bit, which he thought improved its stance.

So far so good. The problem is, no mention whatsoever was made of the significant downside inherent in using wheel spacers. Moving the wheel outward by an inch and a quarter moves it that much farther from the wheel bearings, which—especially when exacerbated by larger, heavier tires—puts massive additional load on those bearings, load that will inevitably compromise their durability. Exactly how much is impossible to say (Bill said he’d be surprised to see bearings last 40,000 miles stressed thusly), but it is inarguable that the modification compromised Toyota’s engineering—that’s just simple physics.

We see this sort of thing too often—laudatory articles boasting of improved ride, better handling, greater compliance, or enhanced power after the installation of extensive (and frequently expensive) replacements for factory parts. Unsurprisingly, these article are often shadowed by advertisements for those same products. (I went to the wheel spacer manufacturer’s site and looked in vain for any warnings of potential detrimental effects to installing them.)

Philosophical aside: Is the urge to “improve” an already decent product a peculiarly male obsession that can manifest itself on almost anything? I offer the legendary Colt Model 1911 .45-caliber pistol as an example. Designed as a reliable, powerful battlefield sidearm over a century ago, it transitioned effortlessly to a reliable, powerful self-defense sidearm for civilian use. But in the last couple of decades that urge to “improve” the 1911 has led to a bizarre market in which you can purchase a basic 1911 for around $500, then with no effort at all spend another three thousand dollars “improving” it. Not making that up—Google “Novak Full House Custom 1911” if you doubt me. Just as with our four-wheel-drive vehicles, many of those accessories actually do improve the utility of the pistol—ambidextrous safeties, tritium sights, modifications to allow feeding of modern hollowpoint ammunition, etc.—but in the drive to enhance the (perfectly acceptable) accuracy of the basic 1911, parts are added and components tightened in such a way that its intrinsic all-weather reliability—the raison d’être of the original design—is compromised. Nevertheless, Novak’s is so backed up with work they’re not taking new orders right now.

Where was I? Right. I’ve written earlier about the physics of tires and suspension lifts (here), noting the number of comments Roseann and I get from people who seem genuinely puzzled that we haven’t installed larger tires and raised the suspension on our Tacoma. When I point out the downsides of doing so, it’s surprising how few had any idea there were any. All they knew about bigger tires and suspension lifts was what they had read in magazines and advertisements.

If you’re modifying a vehicle for extended backcountry travel, it’s vital that you investigate both sides of those modifications. Keep in mind Isaac Newton’s Third Law: For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Space your wheels outward to gain tire clearance and a wider stance, and you increase stress on your wheel bearings. Install larger, heavier tires and you decrease your braking effectiveness and increase stress on steering components. Modify your suspension for greater travel, and you force your axles and driveshafts to flex farther as well, with detrimental effects on CV joints and boots. (And, perhaps, other things: Bill Lee reports inspecting a Tundra lifted so far that the steering torqued the chassis at full lock because the rack could not travel far enough. Bill says, “I love lift kits. They keep me busy removing them and replacing parts.”)

Chris Collard, editor of Overland Journal, sent this along after seeing this post. Good advice.

If, after considering both sides, you decide the type of travel you do would be easier if your vehicle were modified, err on the side of caution. A two- or two-and-a-half-inch lift on a truck with independent front suspension is about the maximum practical without significant downsides. Note the angle on your front axles before and after the lift; you’ll see that they are now running at a noticeably greater angle all the time. Inspect your CV boots regularly. Avoid cheap lift kits that use blocks to raise the rear suspension. When it is moved farther from the spring, the axle will twist under acceleration and braking (this is called axle wrap). Some companies will happily sell you an additional product called a traction bar to help control this—why not just avoid it in the first place? Other kits use an add-a-leaf to jack up the existing rear spring pack. However, add-a-leafs can add stress points to the spring pack. We broke two add-a-leafs before wising up. Some tall front suspension lift kits come with brackets to relocate the steering linkage and even drop the differential—bits that solve one problem and create others.

Remember: The number one function of an expedition vehicle is to complete the expedition. All the ground clearance and compliance and sharp handling in the world will do you no good if something major breaks.

And finally, just so you don’t think I’m being superior about all this: In my gun safe is a heavily modified Colt Combat Commander .45 from Novak’s . . .

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.