Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

A more Affordable aluminum bridging ladder

One of the most basic and effective tools for self-recovery in sand, mud, or snow is what we generically call the sand ladder or sand mat. For decades these typically comprised a cut-down section of WWII surplus PSP (Perforated Steel Planking, also called Marsden matting), originally designed to be linked together to build impromptu runways on boggy ground. Shoved edge on against a tire buried in sand, PSP provides a ramp on which the vehicle can gain traction and climb (especially when combined with some judicious pre-shoveling). PSP is effective but heavy, thus the popularity of a modern version—PAP—made from aluminum.

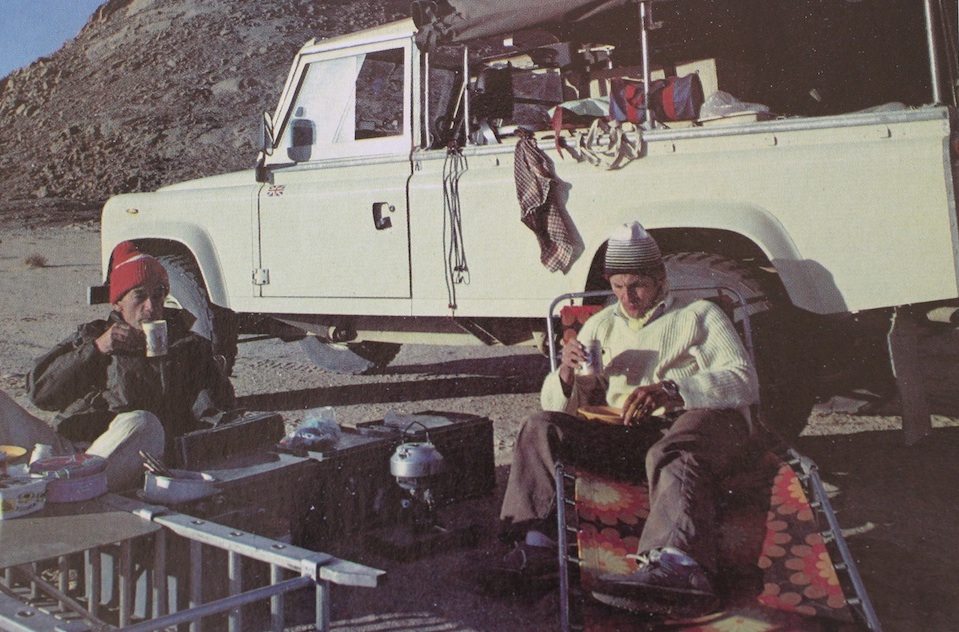

Semi-rigid material such as PSP and PAP works well to provide flotation and traction in soft substrates, but is not stiff enough to be used to bridge a deep ditch, or to function as a ramp to surmount a vertical ledge, unless doubled—in which case the normal complement of two allows only one wheel to be supported. Sahara explorer Tom Sheppard surmounted this problem decades ago by simply ordering a pair of custom-made ladder sections such as one would use at home, but with extra-deep side rails and rungs spaced just 15cm apart. Each section was sturdy enough to provide bridging support for one side of a loaded Land Rover—and with some connecting pieces also served as a convenient framework for kitchen furniture.

Today, plastic sand mats such as the excellent Max Trax offer a lightweight (18 pounds per pair) alternative to traditional versions; however, the Max Trax is still insufficiently rigid to be used as a bridging ladder unless doubled. The connoisseur’s choice for combined traction and bridging duty has for some time been the excellent Mantec bridging ladder (known as a bridgy by the abbreviating Brits), a beautifully trussed and welded structure of aluminum more than strong enough to support a fully laden expedition vehicle. But the Mantec ladders currently run about $650 per pair when you can find them this side of the Pond, and their bulk and weight—42 pounds for the two of them—is a handicap, too.

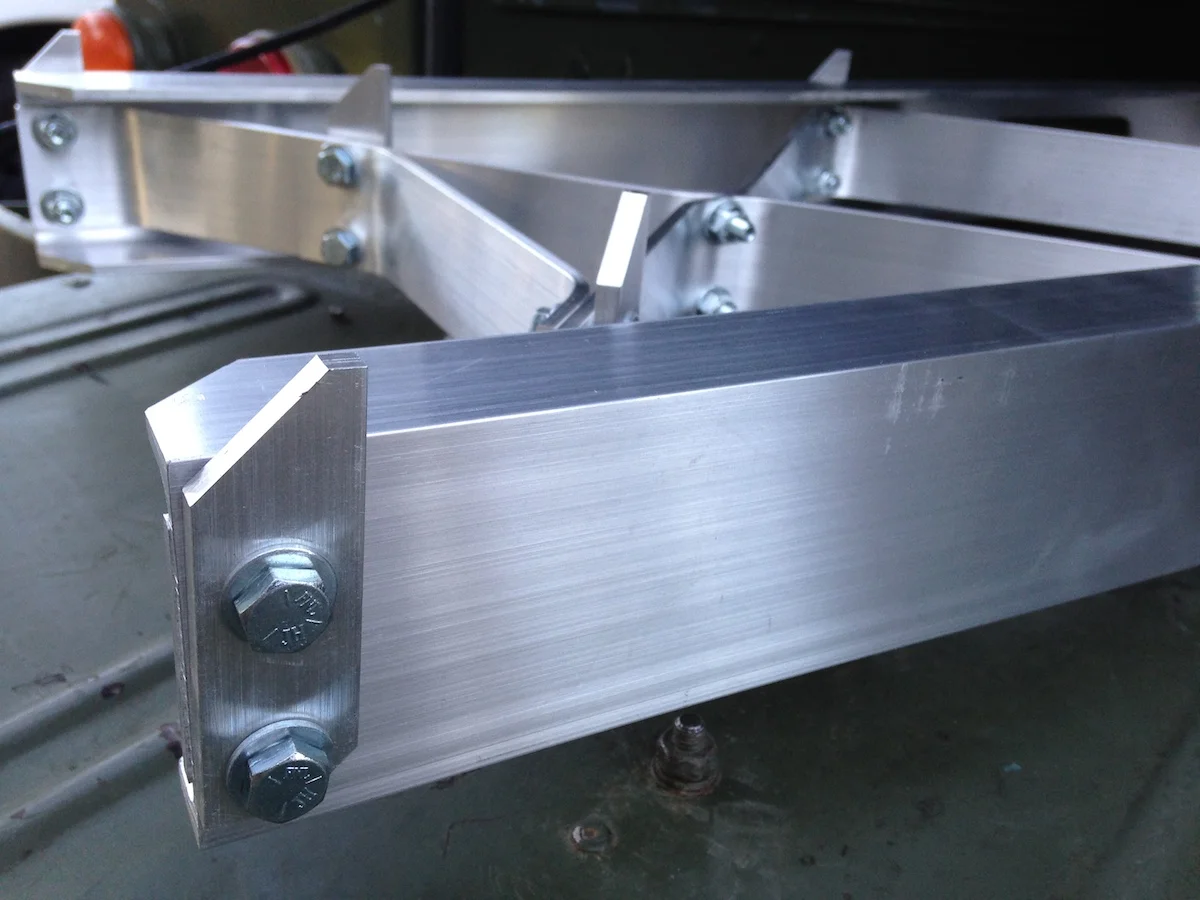

However, a significantly more affordable ($349) aluminum bridging ladder is on the horizon, thanks to Jeremy Plantinga of the newly formed Crux Offroad. Jeremy contacted me a year ago and showed me a few prototype designs before finalizing a design and shipping me this set—which comes disassembled via UPS, saving yet a bit more in shipping costs (a flat $30 to the lower 48).

The main structure of the Crux ladder comprises two 48-inch-long U-shaped side channels and two W-shaped cross treads, with a brace at each end and a total of 12 aluminum grip spikes that extend beneath the rails. The ladder is designed so the tire contacts the cross treads only after passing the ends of the side channels, to reduce the chance of kick-up. The instructions say assembly takes about an hour; I did the first one in 25 minutes and the second in 20. The side channels can be assembled with the U either in or out, depending on the width of your tires—with the U facing in the ladders appear more than wide enough for either the 235/85x16 ATs on our Tacoma or the 255/85x16s on the FJ40. The modular design means it will be easy for the company to tweak dimensions for different applications.

Mantec on the left, Crux on the right

In a quick visual comparison the Crux ladder lacks the monolithic support of the Mantec. It's obvious the Crux will offer less flotation in very soft sand, mud, or snow; on the other hand its open cross treads should significantly enhance traction and reduce kick-out when climbing. At 34 pounds per pair the Crux ladders are 20 percent lighter than the Mantecs (although they are also 20 percent shorter). Last year on the Continental Divide, when an FJ Cruiser pulling a trailer got stalled on some uphill ice, a pair of Max Trax we deployed simply zipped right under the tires when power was applied; the plastic offered no purchase against the ice. I’m willing to bet the grip spikes on the Crux ladders will do better in the same situation. For bridging, Jeremy rates the Crux ladders at 2,000 pounds each, which, given the insight I’ve had into his failure testing, seems appropriately conservative, and more than enough to support most full-size pickups, or a Land Cruiser or Jeep Wrangler Unlimited. Jeremy has plans to develop accessories such as table or bench tops and legs, which would enhance their versatility.

I’m looking forward to field-testing the Crux ladders, and expect they’ll perform well. If you’re intrigued too, they will be debuting and available at the Overland Expo in Mormon Lake next month. I plan to hand over my set to the Camel Trophy blokes to see what they can come up with for on-site testing.

The company's nascent website is here.

Update: I've had a little time to play with them. Supporting the front wheels of a Defender 110 in the middle of the span, the Crux ladders showed essentially zero deflection. Impressive . . .

Another update: The Crux ladders nest securely, located by the traction spikes. When joined, the adjacent handle holes make it easy to carry both ladders with one hand.

The irrational Land Rover . . .

I knew a fellow, a lives-and-breathes-them Land Rover aficionado, who was on his way across Africa in a 109 Station Wagon when the rear differential blew. Someone on a forum, as I recall, referred to the event in terms of a “breakdown”—which elicited an aggrieved response from the owner. This was not a “breakdown,” he insisted. Why? Because differentials are “maintenance items.”

If you are a lives-and-breathes them Land Rover aficionado, or if you know one, you’ll recognize this syndrome. Over the years, and to a greater or lesser extent depending on the model, Land Rovers have become known for being, how shall I put this . . . co-dependent. Because of this, owners are constantly besieged with quips, snarky comments, and jokes. (“Eight out of ten Land Rovers ever made are still on the road. The other two made it home.” Etc.) These are especially likely to come from Toyota owners revelling in their own brand’s sterling reputation. Desperate-sounding ripostes about Toyotas being “appliances” only come off as desperate-sounding—the Toyota owner just smirks and leaves the Land Rover owner grinding his teeth.

Perhaps it was the resulting Maginot mentality that led to the simple defense of not acknowledging breakdowns as breakdowns, and not calling repairs repairs. After decades of association with Land Rover owners, I’ve realized that the word ‘repair’ should not be applied to any procedure being performed on one of their vehicles unless they’ve rigged a steel beam on two A-frames extending side to side through both open doors, and are using three pulley blocks and a team of donkeys to remove something. And even then: A dear (nameless) friend whose Defender’s transmission failed on an epic trans-Africa trip actually excuses it with, “It wasn’t the vehicle’s fault. A part was installed incorrectly at the factory.” Um, okay, Graham. The reductio ad absurdum of this peculiar mental illness is reached when the poor owner begins typing spluttering forum posts such as, “They’re only unreliable if you don’t use them hard enough!”

I can write this without (much) fear of assassination because I have always felt a strong attraction to Land Rovers, and at the moment own two of them. At the same time I can keep one eyebrow raised ironically because I also own an FJ40 Land Cruiser that in 35 years has not once, one single time, left me stranded. In 1978, when I bought it, my choice was between the Toyota or a 1974 Series III 88, at that time a product of the troubled British Leyland group (‘troubled’ and ‘British Leyland’ being completely redundant phrasing). Everyone short of the State Department warned me off the Land Rover, and in retrospect buying the FJ40 was absolutely the right choice. Reliability aside, towing a 21-foot sailboat or a utility trailer loaded with eight sea kayaks would have been problematic with the 88’s 75 horsepower. And then there were those axles . . .

The logical choice . . .

Where was I? Right: The big question, of course, asked by everyone who is not of the lives-and-breathes community, is why? Where does what seems like this blind devotion come from, when there are so many alternatives, however appliance-like they may be?

One simple answer on logical grounds would be that Land Rovers work so well when they work that owners are willing to put up with constant fettling. From the range-topping Range Rover, still unmatched in its combination of luxury and off-pavement prowess, to the Defender, still unmatched in its combination of pliant ride with outstanding cargo capacity, and fine turbodiesel power with excellent fuel economy, Land Rover has been ahead of other marques in numerous engineering details since the 1970s.

But that’s the logical answer, and logical answers are vulnerable to logical ripostes regarding . . . reliability—surely, many would point out, the most critical characteristic of any expedition vehicle.

I think the real answer to the unswerving loyalty of Land Rover owners is the intangible, but undeniable, aura of history and romance that surrounds the Land Rover as it does no other expedition vehicle. Hook up electrodes to the brain of the most loyal Toyota/Nissan/Ford/Jeep owner, and ask him to, quickly, picture a vehicle on an African safari, and I guarantee the diagnostic screen is going to produce an image of a Land Rover, roof rack loaded with jerry cans, plowing through the bulldust of Tanzania.

The romantic choice . . .

Whatever the real reason is, I consider myself immune to such blind unreasoning justification.

Or, I did. Until this weekend.

I drove our recently acquired ex-MOD 110 Defender out to our desert property to do some work on the camping area. On the way out I’d noticed the shifting of the LT77 five-speed seemed to be more recalcitrant than usual (it’s due to be replaced with a later R380, along with a 300Tdi powerplant, soon). Just as I pulled up to park near the cottage, I was suddenly presented with, in the immortal words of the late James Hunt, a gearbox full of neutrals. Uh oh.

I had no factory manual, and no experience with the LT77, so I just got out the tools and began fettling. With the rubber shift boot pulled off, it became obvious the issue lay beneath a shift tower that supported two springs which helped locate the shift lever. With the springs popped off to the side, the lever came out (sending another spring-loaded plunger smartly across the cab, fortunately found). Four bolts undid the tower, and with it off the problem was immediately apparent: The metal and nylon socket into which the lever’s ball fits had come off the operating shaft, in turn because a set screw had come loose. Slide the socket assembly back on, tighten the set screw, tower bolted back in place, shift lever in and springs prized back on, and we’re finished. More or less precise shifting back in operation.

And then it happened.

I was thinking that, if the problem occurred again, I could probably have it sorted in less than 10 minutes. And as I innocently, happily considered that, another thought flowed—smoothly, sinuously, completely unbidden—into my brain:

It hardly even counts as a repair.

I’m doomed.

Or maybe I'm just not using it hard enough?

The Wescotts return from The Silk Road

One day in the summer of 1993 Roseann and I were sitting in a café in the Canadian Inuit village of Tuktoyaktuk, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. We’d been having one of those time-warp conversations with a phlegmatic local whale hunter: He’d ask a question such as, “Where you from?” We’d answer, there’d be a two-minute silence, then, “How’d you get down the river?” We’d answer, then ask him a question: “Lived here long?” Two minutes, then, “Born here.” We were in no hurry, having just paddled sea kayaks 120 miles to get there, so it was a fun way to pass time and—slowly—learn something of the area.

After a while a couple came in—anglos, surprisingly, the first we’d seen since landing the day before. They sat nearby and said hello, and we struck up a conversation that must have seemed alarmingly hasty to the Ent-like whale hunter. They asked how we’d got to Tuk, and when we described our trip expressed open-mouthed admiration. They’d flown from Inuvik, it developed, and had left their pickup and camper there.

And as soon as they mentioned a truck and camper, I realized that the couple was Gary and Monika Wescott. It was my turn to be open-mouthed, as I’d been reading tales from the Turtle Expedition in Four Wheeler magazine for, what, 15 years already by then? I’d devoured the articles documenting the extensive modifications to their Land Rover 109 during the 1970s, had been disappointed but intrigued when they switched to a Chevy truck (which, even more intriguingly, vanished without comment soon after), and then followed the buildup of the Ford F350 that would prove to be the first of a series. Our Toyota pickup had a Wildernest camper on it at the time, but we were saving to buy a Four Wheel Camper of the same type that sat on the F350 Turtle II. Most recently, I’d read along as the Turtle Expedition completed an epic 18-month exploration of South America.

We saw each other over the next couple of days as we all took in the annual Arctic Games, watching harpoon-throwing contests and blanket tossing, and snacking on muktuk. Then we lost touch for 15 years (while they journeyed across Russia and Europe), until reconnecting when I edited Overland Journal.

Since 2009 the Wescotts have been regular instructors and exhibitors at the Overland Expo—until 2013, when they embarked from the show on their latest adventure, a two-year trans-Eurasian odyssey along the Silk Road.

Now we’re delighted to welcome Gary and Monika back from their journey. They will be giving presentations and taking part in roundtables at Overland Expo WEST 2015. Don’t miss a chance to meet these two personable and friendly travelers. Listening and watching as the Wescotts describe their journeys is both entertaining and inspiring, and their latest journey should be fertile ground for good tales.

Best of all, Gary and Monika are genuinely excited to share; there’s not a trace of bravado between them, despite being among the most-accomplished overlanders in the world (and still traveling). They travel because they are passionate about exploring and learning and sharing, not because they are trying to count coup or gain fame. It’s refreshing, and we are glad to have them back.

- Regional Q&A: Russia, Mongolia & Southeast Asia; Friday 2pm

- Regional Q&A: Europe, Eastern Europe & Iceland; Saturday 8am

- The Silk Road; Saturday 11am

- Experts Panel: Top Travel Tips; Saturday 1pm

Explore 40 years of adventures with the Turtle Expedition at http://turtleexpedition.com

The Tacky Tourist Mug

Humans have been collecting souvenirs to commemorate their travels for a long time.

Amber beads from Scandinavia, found in Ireland and dated to around 1,000 BC, are among the first objects to be classified as ‘souvenirs’ by archaeologists—probably because the scientists could figure out no practical use for them, the very definition of a souvenir. By the middle of the first millenium AD, religious authorites in Europe had become so tired of pilgrims breaking off pieces of holy buildings and statues to take home that they began manufacturing and handing out tiny ampullae filled with holy water to stem the vandalism. These soon proved too expensive to produce in mass quantities, so cheaper badges were substituted. Thus we can blame the church for the rows of junk in most modern gift shops.

Wealthy nineteenth-century travelers on the Grand Tour of Europe commonly had compact portraits painted of themselves next to famous landmarks such as the Arc de Triomphe. Anyone else see a direct line of descent to the selfie stick?

These days, as mentioned, the word ‘souvenir’ generally calls to mind Elvis snow globes (the largest gift shop in the world is in Las Vegas), Chinese Inca figurines, and T-shirts. Yet the drive to take home some essentially inconsequential memento of exotic travels remains strong in us. How to assuage it without becoming an item of ridicule in the local paper on one’s death?

Roseann hit upon an excellent solution a few years ago, on a trip to Egypt. We’d hired Land Cruisers with camping and cooking equipment, but the only cups included were plastic throwaways. In a parking lot near the Pyramids she scanned the offerings of a group of vendors, and picked out a spectacularly hideous mug with Pharaonic motifs done in gold leaf. I chided her for contributing to the Chinese-ification of the souvenir trade until she turned it over and found it was made right there. And she had a nice ceramic mug for the rest of the trip, while I drank coffee from Dixie cups (we never found another souvenir mug dealer).

That mug (which she referred to as her ‘tacky tourist mug’), judiciously packed, made it home, and a tradition was born. Now we have an ever-expanding collection of mugs from destinations as diverse as Ushuaia and Steamboat Springs. While some remain decidedly on the tacky side—witness the Pope Mug from Argentina—many others simply commemorate a favorite town or cafe. And we never run out of coffee mugs for visitors.

Worth the space?

All motorcyclists carry that one luxury item they could do without, but which makes the trip so much more comfortable. For most riders it's a pillow, for some it’s a torque wrench or musical instrument. It used to be that chairs fell into that category. Lately, they seem to be on the must-have section of the packing list since so many riders are carrying one. Is it worth the 2 lb. and 14x5” it takes up in the pannier?

I have always been one for simplicity, which usually meant no luxuries. That idea has been forever spoiled after this past Christmas and the purchase of two Helinox chairs and a table. Camping will never be the same. No more sitting on the ground to cook or using a pannier as a chair. The Chair One is perfect for enjoying a morning cup of coffee or relaxing with an evening beer after a long day’s ride. With a conscious decision of not doing much for the day, you can easily spend hours, comfortably, playing games without noticing the compact size of these chairs. The table is made of a taut mesh, providing adequate stability for our travel chess board, and there are two inset cup holders to ensure no game gets spoiled by spilled liquid.

The design is simple and the tent-pole-like aluminum frame dis/assembles quickly. It’s light and strong (can hold up to 320lbs.) and has four legs. Gone are the days of balancing on only two to save space.

After only one weekend, I understand how the Helinox chairs became so popular and found their way into the panniers of many riders—and into mine. For those who don’t have one yet, I highly recommend you give it a try, and lucky for you they now come in a variety of colors to choose from.

Silent impressions of the Overland Expo

Kyle's overlanding setup

By Kyle Rosenberg

Last summer the following post appeared on a popular overlanding forum:

“If you were engaged in an activity or gathering, such as, say, the Overland Expo, or an expedition in which a group effort were necessary to get from point A to point B, who do you feel would be a more challenging travel companion: 1) An international traveler who neither speaks, reads, or writes English, or 2) A deaf person who is fluent in English but cannot speak, hear, or understand English and relies on American Sign Language as his primary means of communication?”

The responses I got to this informal survey appeared to be split three ways, which was what I expected. Some said interacting with the international traveler would be easier, some said the deaf individual, others said it made no difference. It was fascinating to see the rationale many shared for why they chose what they did, and the experiences they had had with one or the other group, both, or neither. I did not disclose to anyone on the forum that I am a bilingual deaf person, so, with the exception of one or two people who replied who had met me previously, this allowed me to collect completely objective perspectives.

With the idea of an experiment forming in my mind, I reached out to Jonathan and Roseann Hanson of Overland Expo to share my thoughts. Since I can lip-read very well, I wanted to try the full Overland Experience package of classes. As we emailed back and forth, however, we decided that I should try even greater immersion. So not only did they sign me up for the Overland Experience package at the upcoming Overland Expo EAST, I also signed up to be on the volunteer crew so I could experience everything there from both perspectives, the attendee and the volunteer. What follows are just a few experiences out of the many I had during the first week of October.

I arrived in Asheville on the Monday before the Expo to start working with the other volunteers and individuals who make up the Overland Expo organization. We spent the next few days transforming Taylor Ranch into what I saw as an overlanding utopia, and in the process I got to know many of the people there, ‘listening’ to their stories and experiences whilst they got to know me and my unique views on the world as a fully-functioning disabled person. Needless to say, it was this group of people I was most comfortable interacting with for the remainder of the week, as they had become comfortable with me and developed their own methods for interaction, whether it was gesturing, speaking slowly and clearly, or picking up on nonverbal cues to adjust seamlessly the prosody of our communication.

Whether it was intentional or a happy coincidence, I was assigned to direct traffic on Thursday, when the majority of the attendees arrived. My location at the midway point on the hill ensured that nearly everyone who camped at and beyond the hill interacted with me throughout the day. While the job was simple and usually did not require more than directions, which I could do happily just pointing my finger, several times I was asked about certain group rendezvous areas, and about showers and toilets. I understood people just fine, as I’m an expert at lip-reading and I often use the power of deduction to figure out what is being said. However, strangers struggle to understand me as it takes time to get accustomed to my unique deaf “accent” when I struggle to pronounce words correctly. A 30-second interaction makes it virtually impossible to accomplish this. Some people reacted much better than others. Some understood me just fine, while others got frustrated and just rolled on to the next person up the hill. I observed a distinct difference in reactions among different ages: Older individuals seemed much more willing to try to understand and interact with me, while younger folks were much more impatient and less considerate. Hmm, something to ponder here!

Come Friday, the Expo had officially started, and part of my experiment was to sign up for as many classes as I could (I believe 11) in several formats, to see which was the most accessible for me, to observe what worked and what did not. I signed up for classes, narratives, slideshows, demonstrations, and roundtable discussions. My observations—obviously slanted by my own cirsumstances—are listed below.

Some narratives were great; others not so. Those who were passionate and animated about their experiences were easy to understand, as the picture they painted of their trips came to life and the vividness of their words made me feel as if I were there. Those speakers also made eye contact with the audience, and this allowed the speaker to adjust his pace and focus of elaboration. But a few just sat, spoke in a monotonous manner, and actually looked downward the entire time and did not use any visual aids. Perhaps those individuals were not used to public speaking, which is understandable but did not benefit me much in the information-gathering process. For someone as dependent on visual cues as I am, this will make or break the whole experience.

All the slideshows I went to I enjoyed immensely, as I was able to reconcile the objectives of the speaker to each picture that appeared as they were set up in a linear fashion, a pathway from the beginning to the end, if you will. It was quite easy to follow, as it is a natural tendency for presenters to point to certain areas or objects in the picture and then expand upon it. That is what I used to determine the content/context of the talking points.

Demonstrations were another favorite, since not only did I get the chance to see how certain things were accomplished in a step by step manner, it was hands-on which speaks to my background in Experiential Education—the philosophy of learning by doing. It also worked in my favor as demonstrations have a built-in pace that allows for clarification and audience participation.

I did not enjoy panels and roundtable discussions as much as the others, because it was extremely difficult to follow along. Often people in the audience would ask questions, and by the time I figured out where it was coming from, the question had already been asked and the answer was in progress. As is often the case with having a few experts on a particular subject, they sometimes talk over each other. As they expand on the person speaking before them, if that is missed, it becomes a snowball effect and the delay in information only gets larger and larger.

What I learned from this experience is that it is much easier to communicate with people one-on-one rather than in a group setting, as I can put in all of my resources to make sure they’re understood instead of jumping around and “resetting” every time someone new participates. It’s exhausting after a while trying to follow everyone as it takes quite a bit of processing in such a short time.

Interestingly enough, the biggest obstacle I had during the weekend was something as simple and natural as nightfall. With little or no light, I can’t read lips. If I can’t read lips, it goes without saying that I’m not going to be able to understand anyone. Even with a roaring campfire, it sure does get extremely dark in the Blue Ridge Mountains!

I’m hoping that I’ll be able to make it out to Arizona for Overland Expo West 2015, but I have yet to decide if I want to reprise the experience I had in Asheville—which was fantastic—or see about bringing a friend who is fluent in sign language and would be willing to interpret the classes and the presentations so I can engage fully, instead of merely being an observer. The overland travel bug has truly bitten me and I intend to embrace it as much as I possibly can.

I want to thank everyone I came across during the week I spent in Asheville. From the time I showed up at the Wedge Brewery for the pre-expo social to the Monday morning cleanup of Taylor Ranch, it was a phenomenal experience that I’ll never forget. The people I met, interacted with, worked with, and shared with are way too numerous to be listed here, but you know exactly who you are.

Kyle Rosenberg currently resides in New Jersey but his heart is in the desert southwest. His vehicle of choice is a 4Runner that is always full of gas and a 1950 Bantam trailer with a roof top tent ready at a moment’s notice to be hitched to travel and explore what the country has to offer. A recent graduate of the Masters Program in Experiential Education at Minnesota State, Mankato, he is currently exploring progressive and innovative bilingual ways of combining the overlanding experience with educational programming for everyone to enjoy whether they are disabled or able-bodied. This will hopefully be achieved through team-building activities, experiential learning approaches and educational outreach. Any and all ideas, proposals, job opportunities, and networking, along with a couch or backyard to visit, are welcomed and greatly appreciated. He can be reached at kylemrosenberg@gmail.com.

Where quad-cab pickups rule

South America could be referred to alternatively as The Land of Quad-Cab Pickups. In the 6,000 miles we drove, the proportion of quad-cab models to standard cabs was at least fifty to one, if not greater.

The manufacturer range is extraordinarily broad. In Argentina, Chile, and Peru, the Toyota Hilux predominates in spite of its age (little changed since 2005). Manufactured in Argentina, it’s normally powered by the 1KD-FTV 3.0-liter four-cylinder turbodiesel, a bombproof powerplant that takes advantage of significantly cheaper diesel fuel prices here, but is beginning to lag in the power department with 172 hp and 260 lb.-ft. (A redesigned Hilux will soon be entering the market, but reports are that engines will be largely held over.)

Two other brands offer newer models arguably superior to the Hilux, at least on paper. The handsome Ford Ranger T6 has a 3.2-liter turbodiesel that produces significantly more power than the Hilux (197 hp and 346 lb.-ft.) ; the Ranger also boasts a greater fording depth.

The Volkswagen Amarok (which means ‘wolf’ in Inuit—and we get the ‘Tacoma’?) manages up to 177 hp and 310 lb.-ft. from a tiny but hyper-efficient two-liter turbodiesel. Despite their more modern design, neither the Ranger or Amarok seems to have cut far into Hilux sales. We also saw a few of the new and impressively specced Chevrolet Colorados, set to give the U.S. Tacoma some competition.

The Mitsubishi Triton appeared to be the second-most popular truck in a lot of areas, despite its (to me) ungainly styling and middling turbodiesel. Speaking of ungainly, in Chile the Mahindra is extremely popular, and I have to admit its wonky looks are growing on me—it’s definitely styling by Bollywood compared to Detroit’s Hollywood, but I like the huge window area.

Much more conservative is the Great Wall Wingle 5—the Chinese managed to combine an awesome brand name with an utterly dorky model name (but then there’s ‘Tacoma’ . . .). How long will it be before a Chinese vehicle manufacturer mounts a serious import campaign in North America?

Korean manufacturer Ssangyong fields a stylish pickup called the Actyon Sports. With all-coil suspension and a long list of family-friendly features, it appears to be aimed at a more urban audience.

Finally, we spotted just an example or two of a mid-size truck called the Xenon from Tata, the Indian megacorporation that owns Land Rover and holds the fate of the Defender in its hands.

And, we had some indication that the South American fondness for quad-cab pickups is perhaps not a recent phenomenon:

Now it can be told . . .

Bear with me for a bit? Sometime in the early 1980s I happened across an intriguing article in a U.S. four-wheel-drive magazine. In it was a photo of a fellow standing in a sandy expanse of desert, next to a very early Range Rover. A line bisected two words scrawled in the sand: ‘Mali’ and ‘Algeria.’ The fellow leaned on a shovel, apparently the tool used to scribe this middle-of-nowhere border.

That was my introduction to Tom Sheppard, ex-Royal Air Force test pilot and the leader of the first west-to-east crossing of the Sahara Desert, the Joint Services Expedition, in 1975. In the years to come I followed his (frequently solo) excursions through the most isolated regions of the Algerian Sahara, often completely off-tracks. In 1999, when I heard he had published a book called Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide that would be available at Land Rover dealers, I drove 120 miles to the swank showroom in Scottsdale, and stood in line to pay for a copy behind wealthy urbanite Range Rover buyers picking out Africa-themed spare tire covers.

Fast forward eight or nine years, when I was fortunate enough to work with Tom during my time as editor of Overland Journal. A year or so later, Roseann and I had the opportunity to meet him on a trip to England. To my amazement, there was not a trace of the ex-test-pilot-Sahara-explorer-RGS-medal-winner arrogance I would have expected. Instead, we were welcomed by a quiet, humorous, and steadfastly self-effacing man who doted on the horses and sheep that grazed on the farmland adjacent to his modest cottage. Over the next few visits we became friends.

Fast forward again to 2014. We’d been trying to convice Tom to publish a fourth edition of VDEG (‘veedeg,’ as he and everyone refers to Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide). The third edition had sold out in half the time he expected. He agreed it was needed—but then sent me a mockup of the proposed cover, which (as you can see from the header image) was a complete shock.

So now, after seven months of exhaustive research and writing on both Tom’s and my part, I can announce that the fourth edition of Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide, by Tom Sheppard and Jonathan Hanson (woo hoo!) will be out in mid-May, with copies also available at the Overland Expo. This edition has received the most extensive updating and expanding since the original, with much more content specifically relevant to North American readers than in previous editions. Total content is up by nearly 20 percent—it's now a 600-page book.

Any verbose attempt on my part to explain what an honor this is would be futile. So I’ll just say I’m thrilled and humbled to have contributed in a very minor way to a classic in the field of expedition literature. If you don’t yet own a copy of VDEG, or if you have previous editions and need to complete your collection, please follow this link and put your name on the waiting list. As before, VDEG 4 will be produced by Tom’s one-man publishing enterprise, Desert Winds, and quantities will be limited.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.