Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

What happens when you . . .

. . . run a 2F (six-cylinder Land Cruiser) engine out of oil at highway speeds? My friend and master mechanic Bill Lee sent this photo from a customer's vehicle:

Yes, all those pieces were in the oil pan when he removed it. A rod seized, came apart, and blew the cam into four pieces.

I wondered to Bill what that must have sounded like. He replied:

"First: BLAPBAMWHACKSCREECHBAMWHACK.

And then it sounded like a Tesla . . ."

Tools 101, part 2

The second proper tool for removing and attaching nuts and bolts is the wrench, and compared with the ratchet and socket system it’s simple—a standard wrench has zero moving parts. Much like a socket, each wrench is sized to fit a specific nut or bolt, and can be had in SAE or metric sizes (or, if you have a British car or motorcycle from the 50s or 60s, the rapidly vanishing Whitworth system).

The working end of a wrench can be of two basic styles. A box-end wrench has an enclosed circular shape, and must be dropped over the top of the nut or bolt. An open-end wrench is self-descriptive: It’s open and designed to slide on the nut from the side.

The box-end wrench works better on very tight and/or damaged fasteners, since it grips all six sides. It’s also less likely to slip off than an open-end wrench. Note that, in contrast to the sockets discussed earlier, the vast majority of box-end wrenches are 12-point rather than six point. The reason is that, in contrast to a ratchet and socket, you have to lift the tool off the fastener each time you turn it. With a six-point wrench this would require a full 60-degree turn—cumbersome at best and impossible in many spots. A 12-point end only requires 30 degrees of turn. Just as with sockets, Snap-on’s Flank Drive system or a copy thereof has become common on all but the cheapest wrenches.

An open-end wrench can slip on a fastener from the side. This is an obvious advantage when there is restricted access from above, or if you need to remove a flare nut on a fuel or oil line where it would be impossible to use a box-end wrench or a socket. (Dedicated flare-nut wrenches have what looks like a box end with one section missing; this allows the end to slip over the fuel or oil line, yet grip the nut on five of its six sides. This helps prevent crushing soft brass flare nuts.) Since an open-end wrench only bears on two sides of the fastener, the potential for rounding off a stuck one is higher. Also, since the open end lacks the inherent rigidity of a box end, the two ears need to be comparatively massive to maintain sufficient strength, and this can limit where the wrench will fit. Finally, an open end wrench must be turned a full 60 degrees to engage the next flat on the fastener, although since most open-end wrenches are offset by about 15 degrees you can cheat this a bit by flipping the wrench over between turns.

Looking at the simplicity of an open-end wrench, you might imagine it would be difficult to improve. However, once again the clever engineers at Snap-on thought outside the box: Their Flank Drive Plus system incorporates a series of grooves and a chamfer in the flats of the wrench jaw, ebabling it to grip the sides of a fastener much more agressively than smooth jaws. As with the earlier Flank Drive for sockets and box-end wrenches, many other companies now produce a similar system. One thing to note is that this modification will mar the surface of the fastener if enough force is applied—no doubt the reason Snap-on also still sells wrenches without Flank Drive Plus.

You could save some space, weight, and cost in your tool kit by buying wrenches that are either all box end or all open end, and which incorporate a different size at each end—14mm and 15mm, 16mm and 17mm, etc. However, because of the mix of advantages and disadvantages of each style discussed earlier, I prefer to accept the extra expense, weight, and bulk, and carry combination wrenches that have one open and one box end of the same size. It happens very frequently when working on a vehicle that one or the other will be the best to use, and it’s nice to have them right there in one tool.

A double box-end wrench (17mm and 19mm) above; a combination wrench (19mm) below.

Other ‘improvements’ you’ll see on this tool might be of less value. Wrenches that incorporate a ratcheting box end are becoming more and more common, and the theoretical advantages to the concept are obvious. The downside, however, is a big one: The head is much bulkier than that in a non-ratcheting head. Since one of the salient advantages of a standard box end is its small diameter, able to fit in very restricted spaces, this pretty much eliminates ratcheting heads from consideration for my traveling tool box. I’ve also tried a couple of ratcheting open-end wrenches, which employ a sliding pawl that moves out of the way in one direction and locks in the other. So far I’ve not found one that felt both smooth and precise, i.e. close-fitting to the fastener. The head, as with the ratcheting box-end counterpart, is bulky, and has to be fully engaged on the fastener to operate—thus those cramped situations where you can just get the wrench over part of the nut will defeat the mechanism. So I’ll maintain my trust in standard open-end wrenches–especially for field use, when simple, pure function is paramount.

Kobalt ratcheting box-end wrenches.

Kobalt ratcheting open-end wrench. Note that both these photos were pirated at a local Lowe's because I have no intention of buying the tools.

What to look for? I like fully polished wrenches, which are far easier to keep clean than those with a blasted finish. If you compare a cheap wrench with a good one you’ll find that the good one, with better steel, will be less bulky, especially around the box end, where less material is needed to maintain strength. This can mean the difference between the tool fitting or not fitting over a fastener close to an obstruction.

A fully polished wrench (above) is easier to keep clean than one with a blasted finish.

With that said, however—while I have broken many cheap sockets, I cannot remember ever breaking a wrench. Therefore, while the Gold Standard wrenches are a delight to use, there are many fine alternatives available at fractional pricing. I’m especially impressed with the American-made Wright wrenches, which are available fully polished and with a Flank-Drive-Plus-type open end called Wright Drive. An excellent source for these (and many other U.S.-produced tools) is the Harry Epstein company (here), in business in Kansas City, Missouri, since 1933. The Craftsman Professional line is still decent, although I’m not fond of their gimmicky ‘Cross-Force’ offset-head version. Their conventional 24-piece fully polished metric combination wrench set is less than $50. Other good brands include SK, Proto, Cornwell, and the Home Depot and Lowe’s house brands. Stanley offers an 11-piece set that is a bargain at around $25, although it stops at 17mm and you really should have a 19 in your kit.

On that note: A comprehensive set should include wrenches from about 6mm (or 1/4”) up to 19mm (3/4”). You can go up to 25mm (1”) or so, but beyond that wrenches begin to get very bulky and heavy (not to mention expensive) for the single size fastener they’ll fit. Unless you have a specific application on your vehicle that requires a wrench, I’d stick with sockets for larger sizes.

A 32mm wrench is getting pretty bulky.

A 19mm wrench compared to the 32mm. For most needs the 32mm socket will suffice.

Finally, I like to store my field wrenches in a roll to keep them organized, quiet, and scratch-free. Unfortunately 95 precent of the wrench rolls on the market simply don’t hold enough wrenches. Nine or ten pockets is standard; a few hold a dozen, yet a full set of metric wrenches from 6mm to 24mm—even if you skip the rarely used 20 and 22mm—adds up to 17. A few years ago I snagged a giant Snap-on-branded roll on Ebay, with no fewer than 21 pockets and a generous extra flap of material that made a superb place to keep other tools out of the dirt. (See the opening photo of Tools 101, part 1.) I just discovered that that Snap-on roll was probably this one with the fancy brand added on so Snap-on could charge double.

Tools 101, part 1

I’ve been teaching a tool-selection class now for several years at the Overland Expo, and while most who attend are grounded in the basics of what tools are what and what they do, an increasing number of people are not. This is an inevitable consequence of the direction in which the world is headed—more and more complexity in our vehicles, fewer opportuities for shade-tree mechanics, more two-income families with simply no time to ‘mess around’ with cars. As well, vehicles have become more and more reliable and their drivetrains more durable in the last few decades. No one these days thinks a thing of handing down a 150,000-mile Civic or Corolla to a college student (and how many of those rack up another 100,000 miles before starting a new career crowned with a glowing Domino's Pizza sign?). One result of all this is the 20-something man who approached me after one class and admitted that, regarding my discussion of ratchet and socket sets, he had no idea how a ratchet and socket set worked. So I thought it a good time to step back and review some basics.

Those of us who venture off the beaten track, away from AAA and perhaps even out of cell-phone range, must assume more self-sufficiency than our pavement-bound friends. There are dozens of things that can go wrong on an overland vehicle, and fixing any of them, from easy repairs such as a broken fan or serpentine belt, a split radiator hose, or dirty battery terminals—even just tightening bolts on a roof rack—up to major events such as replacing a broken CV joint or birfield, is going to require tools.

I stress to my class attendees who plan to travel that even if they have no mechanical ability whatsoever, it’s still important to carry a set of tools. You’ll make a lot of points with any good Samaritan who stops to help if he doesn’t have to dig out his tools to use on your vehicle. And if the choice is between an attempt at a repair, or walking out, it’s surprising how many total mechanical rookies have successfully muddled through quite elaborate procedures using nothing but common sense.

The next thing I stress is that your tools should be quality products from reliable manufacturers. Think about it: If you’ve brought out the tools something has already gone wrong—why risk making the situation infinitely worse by using a poor-quality tool that breaks? With that said, few of us can afford to spend thousands of dollars on a complete outfit from Snap-on (the Rolls Royce of tool makers). So the smart strategy is to prioritize where you spend. If a screwdriver tip snaps, you can usually make do with a substitute. If the 19mm socket you’re using to remove transmission bolts breaks, you are not going to get those bolts off with your Leatherman. So let’s look at some of the elements of a basic tool kit, and their functions, starting with the most critical, and therefore the one on which you should spend the most.

Ratchet and sockets

Virtually all the important breakable bits on your vehicle—as well as many that simply need regular maintenance—are held on by either bolts or nuts. The only two proper ways to remove and install bolts and nuts without damaging them are with a ratchet and socket, or a wrench (not pliers!).

The socket part of the ratchet/socket team is a precisely sized piece that fits snugly over the bolt head or nut. Sockets come in metric sizes (10mm, 12mm, etc.) or SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) sizes (3/8”, 1/2”, etc.) that correspond to the diameter of the bolt or nut they fit. Most new vehicles these days are metric, but a few mix both types. Note that some metric sizes are close to SAE and vice versa—you can use a 19mm socket on a 3/4” nut, for example—but the fit might not be as tight on crossover sockets, which could result in stripping a very tight fastener. (Also, note that a 3/4" bolt will not fit in a hole tapped for a 19mm bolt—the threads are different.)

Look inside a socket and you’ll see why they are referred to as either six or 12 ‘point’.

A 12-point socket is easier to pop over the head of a nut because you don’t have to turn it as far. On the other hand, a six-point socket is a bit stronger, better able to grip a rounded-off fastener—and thus generally better for a field kit. Speaking of rounded-off fasteners: In 1965 Snap-on patented a system they called Flank Drive. By radiusing the apex of each angle in the socket, they enabled it to bear on the flats of the fastener, rather than the corners. This allowed more torque to be applied, and also made it easier to remove butchered fasteners. Once the patent ran out, many other companies copied the system, giving it their own names since Snap-on still has the Flank Drive trademark.

Note the radiused points on the Flank Drive socket, left.

On the other, drive side of the socket is a square hole, and this is where the socket snaps on to the ratchet. The ratchet has a toothed mechanism in its head that allows it to lock when turning in one direction, while ‘ratcheting’ freely the other way. Thus tightening or loosening a fastener can be accomplished with a convenient back and forth movement of the ratchet handle, without the need to lift the socket off the fastener and reposition it. A lever or dial reverses the direction of ratcheting.

The square peg on the ratchet, on which the socket fits, is called the anvil or square drive, and its diameter determines the size of the ratchet: A 1/4” ratchet has a 1/4-inch diameter drive, and all sockets for that ratchet will have 1/4-inch diameter drive holes (that’s why you’ll see confusing references to, for example, a 3/8” socket for a 1/4” ratchet). A 1/4” ratchet is suitable for light-duty fasteners. A 3/8” ratchet is perfect for most general automotive work, and should be the first set you buy. A 1/2” ratchet is what you’ll need for more heavy-duty jobs. In terms of the range of fasteners each will handle, there is much overlap, but in general I think of my 1/4” ratchet set as suitable for anything from 4mm up to 12mm fasteners; the 3/8” works well for anything from 8mm up to 19mm, and the 1/2” set is great for 14mm on up. I rarely bother carrying a 1/4" socket set in our vehicles; the two larger sizes suffice for everything.

Left to right, a 1/4", 3/8", and 1/2" ratchet.

The number of teeth in the ratchet head has a bearing on how well it works. Hold the anvil between your fingers and turn the handle while counting the number of clicks it makes rotating 360 degrees. Thirty six clicks equals a 36-tooth ratchet, etc. Years ago most ratchets had 24 or 36 teeth, but lately the count has been going up, and today many ratchets have 72 teeth, and some now boast 80 or more. Why does this matter? Aside from a nicer feel, a finer tooth count means fewer degrees of swing before the ratchet clicks to the next tooth; this can be critical in tight spaces when you have little or no room to swing the handle. On one field repair I had a couple of years ago, my 80-tooth ratchet had exactly one click of free movement to remove a vital but nearly inaccessible nut. It took me 15 minutes to get that nut off, one click at a time—but I got it off. One caveat: It’s easy to make a coarse, 36-tooth ratchet strong, but when you get up around 80 teeth it takes better engineering to ensure adequate strength and resistance to skipping and ‘self-reversing’. So quality becomes even more important.

Materials: It used to be that ‘forged’ and ‘chrome vanadium’ or ‘chrome molybdenum’ were pretty reliable signs of a quality ratchet set. Unfortunately even the cheapest offshore brands now forge tools from chrome vanadium or chromoly, so that’s not on its own a reliable standard. You can easily forge a poor tool from chrome vanadium steel—the difference in a good tool will stem from the purity and mix in the alloy, the heat treating, the finish, and the precision of the fit on the fastener. The best way to ensure quality is to stick with a reputable brand (see below); but other features will help you identify a good set.

What should you look for in a 3/8” ratchet set? Start with the basics. The set should include:

- Ratchet

- Two extensions, one short, one long

- Standard-depth sockets from around 8mm to 19mm (or 1/4” to 3/4”)

- If possible, deep sockets from around 10mm to 19mm (These can be purchased separately if necessary. Deep sockets are used when a bolt protrudes far enough from the nut that it bottoms out on a standard socket.)

- Universal joint (to help access partially blocked fasteners)

- A sliding T-handle is nice. It’s a backup in case your ratchet breaks, and sometimes can access places where the bulkier ratchet head won’t fit.

- Some sets will include a pair of spark plug sockets, but these can easily be added later.

- In a 1/2” ratchet/socket set, look for standard sockets from about 12mm up to at least 25mm (32mm would be better). I don’t worry about deep sockets in a 1/2” set; I’ve rarely if ever needed them. For your 1/2” set you’ll also want a breaker bar for extra leverage on big drivetrain fasteners. Most breaker bars eschew a ratchet mechanism to retain ultimate strength—once the fastener is loosenedyou can switch to your standard ratchet. An 18-inch long breaker is sufficient for almost all tasks.

A superbly comprehensive and compact socket set from Britool, including standard and deep SAE and metric sockets, a sliding T handle, extensions, a universal joint (lower left), plus screw, torx, and hex fittings with an adapter. Sadly no longer made; the newer Britool products have diminished in quality.

In addition, many possible extra features are nice to look for, although it’s unlikely you’ll find all of them in one set.

- Knurled extension. This grippy area helps you to spin on (or off) a fastener before you need the torque suppled by the ratchet.

- Wobble-tip extension. A slightly rounded tip on an extension allows the socket to work at a slight angle, if an obstruction prevents you getting the ratchet directly over the fastener.

- Hex fitting. A few extensions come with a hexagonal section near the top, which allows you to apply a wrench to turn it if you cannot get ratchet on it, or if the ratchet breaks. (The more alternative and backup ways you have to accomplish a field repair, the better.)

A ratchet extension with a knurled section and a hex fitting for wrench.

A standard (left) versus wobble-tip extension.

- Some ratchets come with rubber or plastic ‘comfort handles’. These are definitely more comfortable, and prevent scratching if the handle bangs into sheet metal or paint; however, they’re also more difficult to keep clean. Fully polished ratchet handles are much better in that regard. It’s pretty much personal preference.

- A quick-release button is handy for removing sockets from the ratchet—otherwise the spring detent ball that holds the socket on can require a strong tug to overcome.

- Personally I like to retain the blow-molded plastic case that many socket sets come in. While it adds more bulk to the tool kit than if you simply dumped everything in a bag, the case keeps everything organized and easy to locate, it reduces wear on the tools, and—above all for me—it makes it easy to see if you’ve left out any sockets or other items when you’ve finished the work.

- You’ll see so-called ‘pass-through’ socket sets that eliminate the need for deep sockets. I’ve found these to be less than desirable because the components are very large in diameter and don’t work well in confined spaces. Also, they’re incompatible with standard sockets, so if you break one you can’t easily borrow a replacement or find one in some backwoods hardware store.

So what about brands? As I mentioned, the socket set is the most critical component of your tool kit in terms of quality, so if you’re going to splurge and shop at snapon.com or mactools.com, now’s the time to do it. Just make sure your payments are current on the Amex Platinum. (You can also do as I do and haunt eBay for used sets.)

Setting aside the gold standards, I’m very partial to the Facom (pronounced “fahcomb”) brand. Described as ‘France’s Snap-on’, most of their tools are now produced in Taiwan, but the quality control seems exceptional. Bahco makes some very nice boxed sets, although they rarely seem to include deep sockets.

A high-quality Facom 1/2" set with a comprehensive assortment of sockets.

SK tools makes most if not all their sets in the U.S. After a decided dip in quality before a reorganization, it seems to be back again. The finish is really good, although the ratchet I tried only had a 40-tooth head—interesting how clunky that formerly standard count feels after getting spoiled with 80-tooth heads.

Stepping down a notch, but still functional, is the Sears Craftsman Professional line—as distinguished from the standard Craftsman line, which has lost quality over the last few years with a switch to offshore production. Stick with sets that include the fully polished ratchets and you’ll be okay. The thin-profile ratchets are nice, and they have 60-tooth heads.

Home Depot’s Husky line is not bad, although their ratchet design is an annoyingly blatant ripoff of the Snap-on style. But the prices are excellent and the tools have a lifetime guarantee (which, remember, is great but of little immediate value if the tool breaks in the field). Lowe’s Kobalt brand seems well-made, and the stores I've been in carry a wide selection. They make a 40-piece SAE and metric 3/8” set with a 72-tooth ratchet that is a bargain at around $30, although, again, there’s that Snap-on-esque handle (insert eye roll).

Once you've got a 3/8" and 1/2" socket set, you'll be ready for the companion tools for removing and attaching fasteners: Wrenches.

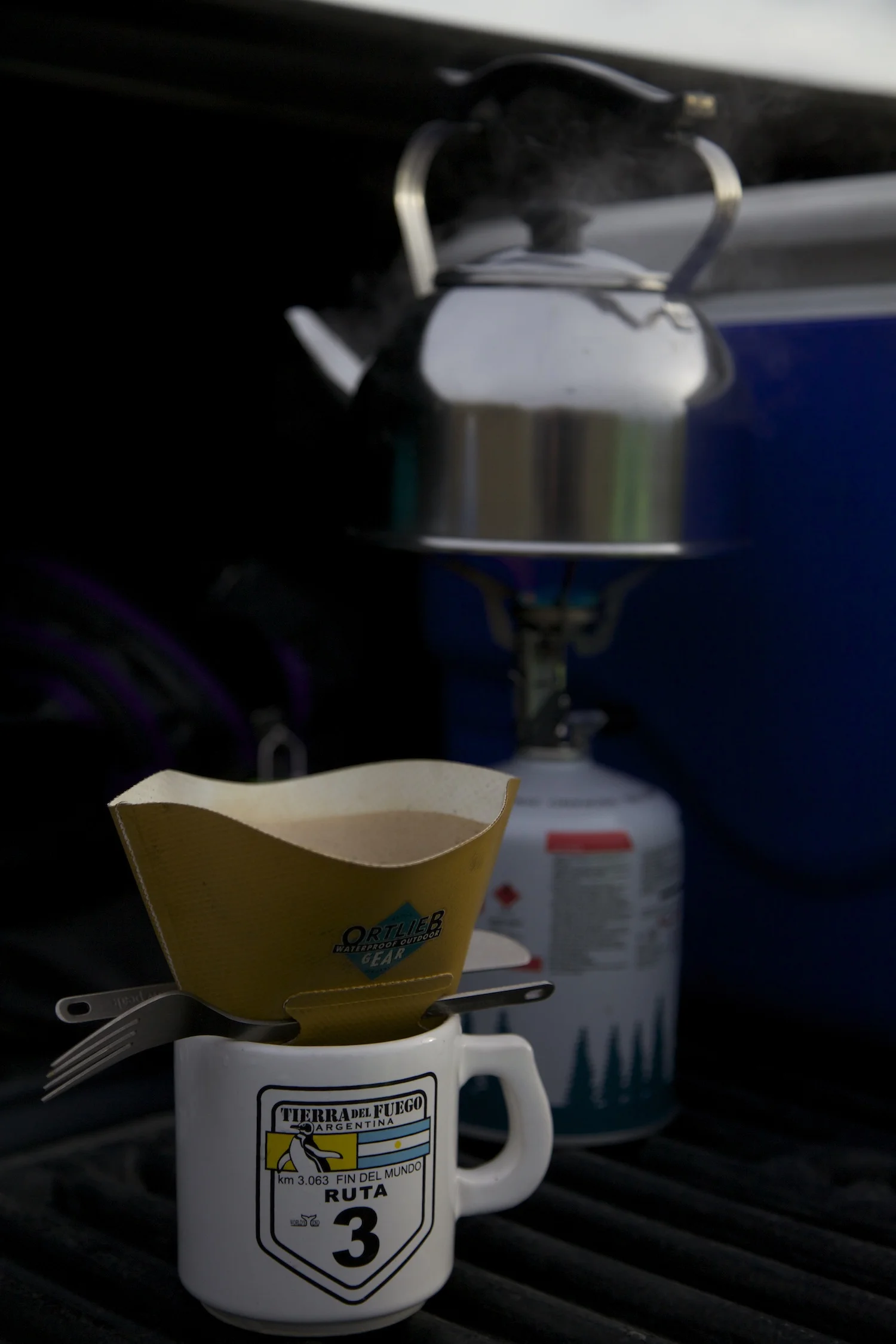

All you need for good camp coffee

Snow Peak Giga Power stove, MSR Titan kettle, Snow Peak 450 mug, Ortlieb filter holder

Of all the challenges facing overland travelers, none results in more angst or 50-page forum threads than the problem of how to make a good cup of coffee when you’re on the road. Vehicle breakdowns, border crossings, terrorism, ebola—all pale as insignificant in comparison to that moment when you must crawl out of a warm sleeping bag and jump-start your metabolism.

In this respect, tea drinkers have it easy: Drop a PG Tips bag in a cup, add boiling water, and Bob’s your uncle. Of course, we coffee drinkers might hint that the effort involved is a clue to the worth of the resulting beverage. To which the tea drinker replies archly, “Tea built the British Empire!” To which we reply slyly, “What empire?” And so on . . .

Where was I? Right. As a reformed coffee Neanderthal (30 years ago my ‘coffee’ was powdered General Foods Suisse Mocha—which, to be . . . generous, was easy to make while camping), my first attempt at making quality coffee in the field was simplicity (and economy) itself: a #2 Mellita-style paper filter and holder suspended over a cup, filled with good fresh gound coffee, and poured over with (near!) boiling water. It was quick, waste-free, and with the innocuous grounds dumped on nearby plants, the used filter took up zero room in the trash, or could be burned on that night’s fire. Cleanup was a few tablespoons of leftover hot water to rinse the cup. It was a perfect system for the needs of a camper, even when traveling by motorcycle.

However. The very simplicity of the system made me vaguely uncomfortable as a born-again coffee snob. Sure, it seemed to taste as good as anything I had elsewhere, but was it just the setting that made it seem so? Was I somehow cheating in the elite club I’d joined?

Thus began a rather prolonged binge of consumerism during which I tested every sophisticated coffee-making apparatus on the market: mocha pots, French presses, double-wall French presses, double-wall-double-filter French presses, 12-volt drip makers, the ‘Soft Brew’—a beautiful ceramic thing with a stainless microfilter—the Aeropress, and others I’ve forgotten.

All made fine coffee. A couple even made coffee I convinced myself might be incrementally richer than my original system, although my opinion might have been subconsciously swayed by how much I’d spent on each device. The AeroPress was excellent and lasted longer than most others. But after a while I realized that every single one I tried shared two significant disadvantages for camping: They were bulky, and they were complex and thus took an inordinate—sometimes scandalous—amount of precious water to clean. In Jellystone Park with a spigot at each campsite the latter wasn’t an issue, but in the field with 20 gallons of water (in the Four Wheel Camper) or two (on the motorcycle), losing a pint or more every morning hurt.

It was about the time Roseann stood in front of an open kitchen cabinet and said, “Do you know how many coffee makers are in here?” that I realized I’d been missing the obvious. What I needed was a system that made good coffee, and was also compact and didn’t take a lot of water to clean. In other words—you guessed it—I needed a #2 Melitta-style paper filter and a filter holder, and some good fresh-ground coffee.

So I’m here to say that the ultimate camp coffee maker is also the simplest, and the cheapest—unless you’re a motorcyclist or bicyclist and spring for some titanium bits. Here’s what I use; this list is easy to modify to go lightweight ($$) for bicycling or motorcycling, or weight-be-damned (¢) for four-wheeled travel.

Kettle: MSR Titan. The titanium Titan ($50) is one of those rare pieces of equipment I’ve used over the years that is simply above criticism. At 4.2 ounces it adds little to the baggage. Its .8-liter capacity is perfect for one person. The Titan is as wide as it is tall, making it stable on a micro-stove. Stay-cool handles and lid lifter make it easy to manage. It serves equally well as a kettle, cook pot, bowl, or mug if you’re on a tight weight budget. And a standard isopro fuel canister drops neatly inside, along with several models of foldable microstove. Of course if you’re traveling in a truck any cheap stainless kettle will do—we picked one up in Ushuaia for under $15 for a trip through South America.

Mug: Snow Peak 450 double-wall titanium ($50). The 450 holds a proper cup of coffee (14 ounces worth) and keeps it hot for ages. In fact the only downside to this mug is that it’s essentially worthless as a handwarmer—the thing just does not conduct heat. You could shave off a couple of its 4.2 ounces (as well as 20 bucks) by going to the single-wall version, but the insulated one gives you better excuses to put off packing up on a lovely morning. Driving a Land Cruiser and don’t need a $50 coffee cup? Any Tacky Tourist Mug will suffice.

Stove: There are a lot of really good canister microstoves on the market for motorcyclists. I still like my Snow Peak GigaPower, but their newer LiteMax is excellent as well. Alternatives include the MSR Superfly (and of course MSR’s legendary liquid-fuel stoves), the Primus Express, and the Optimus Crux. Any of these will fit inside the Titan pot on top of a canister. For the Land Rover? Take your pick of larger canister or propane stoves. The Partner Steel stoves are superb, stable, expensive, and indestructible. A smaller option is thesuperb, stable, expensive, and indestructible single-burner Snow Peak Baja Burner. And for those who are rolling their eyes and thinking ‘gear snob,’ I carry in my FJ40 a 10-year-old single-burner propane stove from Stansport that cost all of $12.50 at the time ($25 now), and works just fine.

Holder: Ortlieb filter holder ($12). Made from the same indestructible material as the German company’s indestructible luggage, this filter holder folds flat, takes up zero room, and weighs a scant ounce. You prop it over your cup using anything handy—twigs if need be, your Snow Peak titanium utensils if you got ‘em. Mine came with only one exit hole and was glacially slow, so I snipped an extra hole in the other corner, which worked perfectly. The Ortlieb holder works just as well in a truck kitchen as on a bike, but the standard plastic Mellita filter holder works even better, and costs about three bucks at a hardware store.

Coffee? Well, see here—or, if that's a bit much and you cannot access locally roasted beans, most grocery stores carry Peet’s Coffee Major Dickason’s Blend, which is excellent. And for those who, like me, adulterate their coffee with half and half, I give you the Mini Moo. Single-serving size, no refrigeration needed.

Tacky tourist mug, $15 kettle

Update on crappy tents

When the article below was shared on Facebook, I got a lot of comments. Many were in complete agreement, and related the writer's own experience with either good or bad gear. But there were several diatribes from those who accused me of being elitist—despite the fact that I listed several companies that make decent tents for under $200—and an extraordinary claim or two about cheap tents performing beyond what I would consider, er, likely, such as standing up to hurricane-force winds. Obviously it would be impossible for me to either prove or disprove such a thing; however, in counterpoint I give you this photo, which I took on the coast of the Sea of Cortez some years ago, when Roseann and I were instructors at the Audubon Institute of Coastal Ecology.

Note the sea state and lack of surf or whitecaps. The breeze was blowing at what I estimate was no more than 25mph, yet this motley batch of department store tents was clearly in dire straits. If I recall correctly, at least three of them wound up completely trashed with broken poles and torn fabric, despite attempts to guy them out and stake them properly. Several others were simply uninhabitable. Note, however, the green Timberline tent on the far right, and, in the far rear, the white Sierra Designs dome—a good sized one—each of which shrugged off the wind with zero drama.

I'll say it again: It's stupid to economize on your tent.

Say no to cheap tents!

It happens again and again. I’ll be cruising some forum or another, and in the camping section there’ll be a new thread titled, “Recommendation for a good tent?”

Oh boy! Buddy, you’ve come to the right place, I’ll think. I’ve been testing and reviewing tents for three decades (and using them for a lot longer); I own, at last count, 16 of them, and I can induce that Dear God, get me away from this lunatic look of panic in the eyes of any conversation partner at a party with talk of thread counts, aluminum alloys, and the stunning superiority of silicone fly treatment over polyurethane. “Wait!” I grab her arm as she sidles away. “Did you know that ‘denier’ refers to the weight in grams of nine thousand meters of a single filament of the fabric?” “Really? How nice. Oh golly!” (Glances at watch.) “I just remembered I have an appointment for an appendectomy! Bye!”

Where was I? Right: So I click on the thread, and the first line is something like: “I need a tent for motorcycle travel—what’s good for under $100?”

My shoulders sag, I look at the ceiling and close my eyes. Sigh . . .

Think about this for a moment. When you are traveling and camping, your tent is your home—your last line of defense against rain, wind, cold, and bugs after a long day driving or riding. You can survive with a cheap sleeping bag and a good tent, but if your $39.95 Costco dome tent leaks in a shower, or collapses in a breeze, the best sleeping bag in the world will not keep you comfortable—or, in marginal conditions, even safe. Sleeping well is critical to maintaining health on the road, and alertness while riding or driving. So, how can I put this diplomatically? It’s stupid to economize on your tent.

I learned this lesson early on—like, when I was 10 or 11. Desperate to own a “tent,” I spent—what, $2.99 at the time?—on one of those ghastly plastic ‘tube tents’ to carry in my military surplus rucksack. A single breezy night at Seven Falls north of Tucson, with my German shepherd, convinced me—and the dog—of the hilarity of the concept of sleeping inside an open-ended trash bag. It was a lesson that morphed into an appreciation for the value of good equipment of all kinds—a philosophy that was reinforced during my years as a sea kayaking guide, when I accumulated a cheap-tent repair kit of heroic proportions for those clients who refused to believe a tent should cost more than lunch.

So what goes into making a high-quality tent, and how do you shop smartly to make sure you’re getting one?

While there is some overlap, tents really need to be divided into ‘backpacking’ designs and larger ‘family’ models. Weight is critical on the former, so material choices need to be more sophisticated than on the latter, where a few pounds makes little difference. I’m going to concentrate on lightweight tents here, so let’s look at markers for a tent that will keep you safe and comfortable no matter what the conditions. Note that these parameters will change for family tents; they are not universal. (Much of the following information, and more, is in the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide, fourth edition.)

Poles. This is your first indicator of quality. Do not buy a tent equipped with fiberglass poles joined by metal ferrules; they will not stand up to even moderate breezes and can splinter asunder when stressed. You want aluminum alloy poles from either Easton or DAC (Dongah Corporation). These companies use alloys in the 7000 series and argue at length whether 7001 is better than 7075, etc. All are excellent when properly heat treated. Ultralightweight tents might use poles as small in diameter as 8.5mm (.334”); those for larger three- or four-season tents will be 9mm to 12mm. Some manufacturers slightly pre-bend the poles before heat-treating; this reduces the initial stress on the pole when pitching the tent. (The only possible higher aspiration in tent poles would be the extremely expensive carbon-fiber versions from Easton, available on the company’s lightest three-season tents—I note they’re not provided with their four-season models, which makes me wonder if they’re completely sorted yet.)

Aluminum alloy poles, such as these from Easton, are the only proper choice for a quality tent.

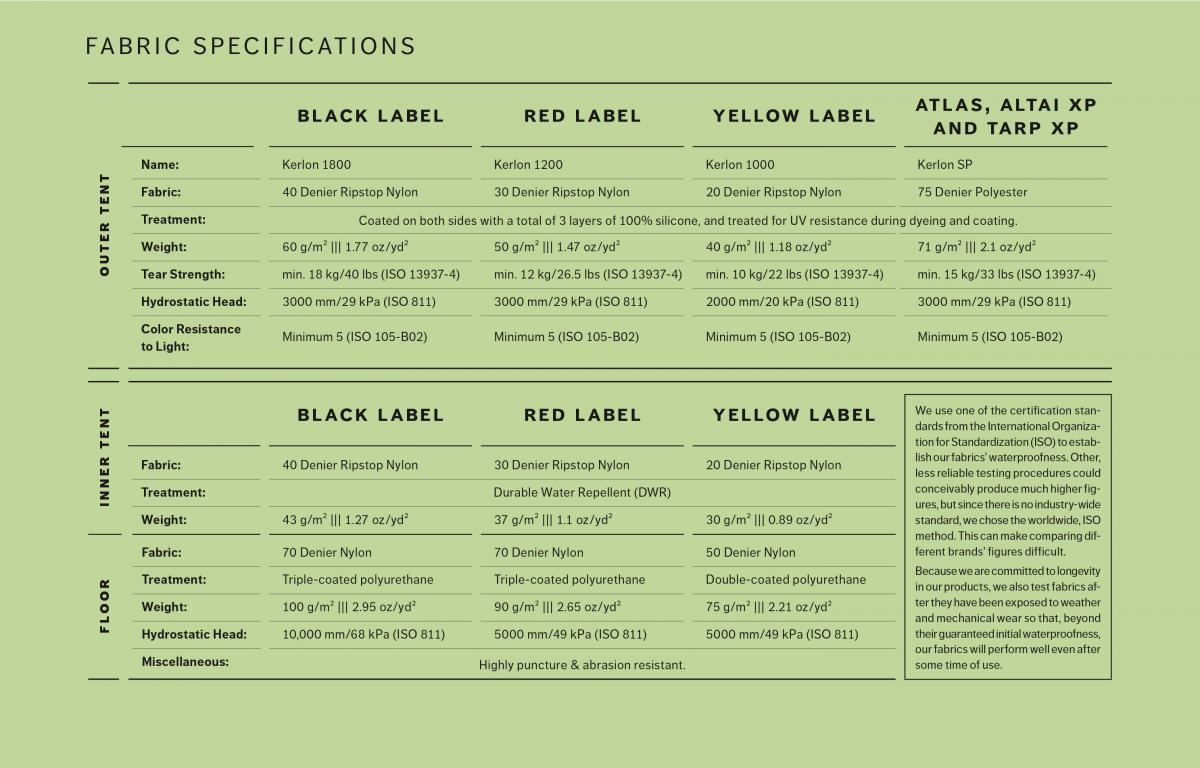

Fly. The separate outer, waterproof layer of your tent will be made from either nylon or polyester. Nylon is stronger by about 15 percent, and more elastic. However, it is also much more susceptible to UV degradation, and is hygroscopic—the fabric absorbs (and chemically bonds to) water. Either will work, but overall, unless nylon is expensively silicone-coated (see below), polyester is probably superior. The weight of flysheet (and many other) fabrics is measured in denier, which really is calculated as I told my captive conversation partner above. Practically speaking, a flysheet made from 10-denier material would be very light indeed; most lightweight tents use 30 to 70-denier fly fabric.

Coating. Since neither nylon nor polyester flysheet material is waterproof on its own, it must be coated, and this is what separates cheap-to-good tents from really superior tents. The former employ polyurethane, which is applied to the underside of the fly. Why the underside? Because polyurethane is even more susceptible to UV degradation than the material. To keep the fabric above the coating from being soaked (and to add a bit of UV protection), it is coated on top with a DWR (durable water-repellent) treatment, usually a fluoropolymer applied at the production stage. Unfortunately the ‘durable’ bit is misleading: DWR coatings wear off rapidly with use. When this happens, the polyurethane will still keep the tent underneath dry, but the fly will soak up water, which in the case of nylon will induce stretch that compromises a taut pitch, and in either case will facilitate the growth of mold if not thoroughly dried. Aftermarket DWR treatments are available to rejuvenate the coating, but must be considered a frequent chore to remain effective.

A superb Hilleberg Soulo single-person tent, well-guyed and staked against Grand Canyon katabatic gusts.

There’s more. Polyurethane coatings formulated with a polyester base are subject to hydrolysis: stored damp, water molecules break down the polyester molecules. Ever pulled a tent out of storage and found it smelly and stuck to itself? That’s the (irreversible) result of hydrolysis. Polyester coatings made with polyether or polycarbonate bases resist hydrolysis much more effectively—but expect a blank look when you ask your outdoor-store sales clerk which is in the tent you’re considering.

Much, much better than polyurethane coating is silicone, which actually embeds into the fabric and strengthens it—in fact it would not be wrong to refer to such material as silicone-reinforced. A silicone-treated flysheet is so water repellent that a good shake will leave it practically dry. Some manufacturers combine a polyurethane coating on the underside of the fly with a silicone treatment on top—much better than PU/DWR, but not as good as double-impregnated silicone. Downsides? Cost—significantly higher than PU—and the fact that seam tape will not adhere to silicone; seams must be sealed with liquid sealant (you’ll need special repair tape for tears as well, although tears will be less likely in the first place, and less likely to migrate). It would not be exaggeration to say that if the fly of your tent is double-silicone-treated nylon or polyester, you can pretty much be assured the rest of the tent will be first-class as well. Since you can expect a silicone-treated tent to last far longer than one coated with polyurethane, it may well be less expensive in the long run.

Waterproof fabric is rated by something called hydrostatic head, which refers to the height reached by a column of water above a sample of fabric before it starts to seep through. The generally accepted minimum standard for a fabric to be considered waterproof is 1000mm; most flysheets exceed this by a substantial amount. Floor material—which is subjected to direct pressure against water—should exceed 3000mm.

Floor. Nylon—logically of a heavier denier than the canopy or fly—is the preferred material for tent floors, and almost all are polyurethane coated (exceptions include Stephenson and Terra Nova, see below). You want a ‘bathtub’ floor, which means the floor material extends a few inches up the side of the otherwise breathable canopy, to prevent pooled or running water gaining entrance. Logically, the fewer seams in the floor, the better. My old Marmot Taku had a floor with no seams at all, but few types of suitable fabric come in sufficient widths any more, so most tents will have one seam up the middle, which should be taped from the factory or sealed by the owner.

Canopy. The inner wall of most tents is non-waterproof, breathable nylon, to help dispel condensation. While this helps, flow-through ventilation is much more effective at minimizing both condensation and related cold-weather internal frost. Ideally you want a ‘chimney’ effect, in which cool air is drawn in near the floor, and warm, moist air rises naturally and exits via high vents. Tunnel-shaped tents with one end higher than the other excell at flow-through ventilation; dome tents with no peak vent are very poor at it.

A chart from Hilleberg showing various fabrics used in their tents.

So-called three-season tents will have fewer, sometimes smaller-diameter, poles, and a canopy with larger areas of screen (no-see-um netting); it might even be all screen so that on clear, balmy nights one can leave off the fly and remain protected from flying and crawling bugs while enjoying the breeze. A four-season tent needs to be sturdier to withstand storm-force winds and snow loads, so will have more and thicker poles, plus tie-outs to help anchor the structure. Many four-season tents have large screen sections that can be closed off when necessary, making them adept at all-season use.

Size. There are no universal standards that quantify a ‘one-person’ versus ‘two-person’ versus ‘three-person’, etc. tents. Generally speaking, 30 square feet is minimum for two people, 35 or 40 is more comfortable, and 45 or even 50 is not out of the question for a couple if you might be tentbound for periods due to extended rain. Floor area is not the only arbiter of comfort: A 40-square-foot dome tent with near-vertical walls will be much more spacious than a 40-square-foot A-frame tent with steeply sloped walls. Vestibules help a great deal to keep boots and stoves out of the living area. Poled vestibules, which create more overhead clearance, are better for cooking, to keep heat away from the fabric.

Free-standing tents are easy to move around if you decide on a new view (or to upend and shake out to clean), and nice in the few locations (such as slickrock) where it is simply impossible to use stakes, but otherwise the feature is highly overrated. All tents should be staked down at all times. Two sleeping bags and a couple of air mattresses do not comprise sufficient ballast—I watched a tent thusly weighted clear the top of a saguaro cactus by ten feet after a brisk gust off the Sea of Cortez caught it.

Very, very few tents come with stakes that are worth a damn. Worst are the soft round aluminum pegs with a hook on the end; I regularly demonstrate the value of these by bending them in my teeth. Any stake that is round in cross section will have less holding power than one with more frontal area to resist sideways pull. Tempered alloy stakes of either T or V cross-section, included with high-quality tents from Hilleberg, for example, are pretty good; however even these are still too small to properly anchor a tent in anything less than perfect holding ground. I wrote about a good aftermarket stake here.

Geodesic dome tents—with a pole structure that creates triangulated reinforcement—are generally more intrinsically stable in side winds than tunnel tents employing parallel hooped poles. But the latter can be superbly stable when pitched end-on into the prevailing breeze, and will do just fine in a crosswind if guyed out properly. My Marmot Taku seemed simply immune to winds from the back; it would just hunker down and tauten and I’d sleep like a babe. Until a client woke me up . . .

A North Face VE25, one of the original geodesic dome tents.

Speaking of the Taku . . . single-wall tents, which typically employ a canopy of some waterproof/breathable laminate, are attractive in their light weight and simplicity, but generally of limited value outside mountaineering expeditions, due to the hugely increased risk of condensation. Sit inside a single-wall dome tent in a cold rain and you might think the fabric itself is leaking, there’ll be so much condensation. (The steeply sloped Taku had such excellent chimney ventilation this was not a problem.)

So, which tents to look at? Companies such as Mountain Hardwear, Marmot, Sierra Designs, Nemo, Kelty, MSR, and Big Agnes make tents of good quality, using excellent aluminum poles but standard PU-coated fly material. Redverz and Lone Rider make nearly identical tents designed around a ‘bikeport’ that shelters a full-size motorcycle.

Want to step up in quality? Look at Hilleberg, the Swedish maker of superb fabric shelters that justify their high initial cost with top-notch construction and materials, including triple-coated silicone fly material. My Hilleberg Staika is a comfortable two-person dome with dual vestibules and entrances, and enough stability (and auxiliary guy lines) to anchor it in anything short of a storm with a name. Yet both doors have screen panels large enough to make the tent fully summer-functional. It’s also completely free-standing, even with the vestibules. My bicycling tent is an Anjan 2 GT, a four-pound tunnel tent with a poled front vestibule large enough to cook or bathe in. If I were off on a really extended journey, a Hilleberg tent would be my first choice.

British company Terra Nova also makes very high-quality tents, including the Laser Photon 2, a (tight) two-person tent that weighs just two pounds. I note that some of their models use PU-coating—hard to justify given the premium prices. Check the specs on the model that interests you.

Iconoclastic nudist tentmaker Jack Stephenson has been using hyperlight silicone-coated nylon in his tents for decades, along with oversize, thin-wall, pre-bent poles that are much stronger than their scant heft would suggest. The result is a spacious two-person tent that weighs three pounds—lighter for its floor area than any other four-season tent of which I’m aware. Sadly there is no vestibule—although the prickly Stephenson will scoff if you suggest his products are less than perfect.

Finally, at the Overland Expo East I was introduced to local (as in Asheville) tent maker LightHeart Gear, sewing featherweight tents originally designed for trekkers, and employing siliconized material and either trekking poles or standard aluminum replacements. I’ve not yet tested one, but the display models certainly held up to the wet Expo weather with no trouble. Worth checking out.

Good people . . .

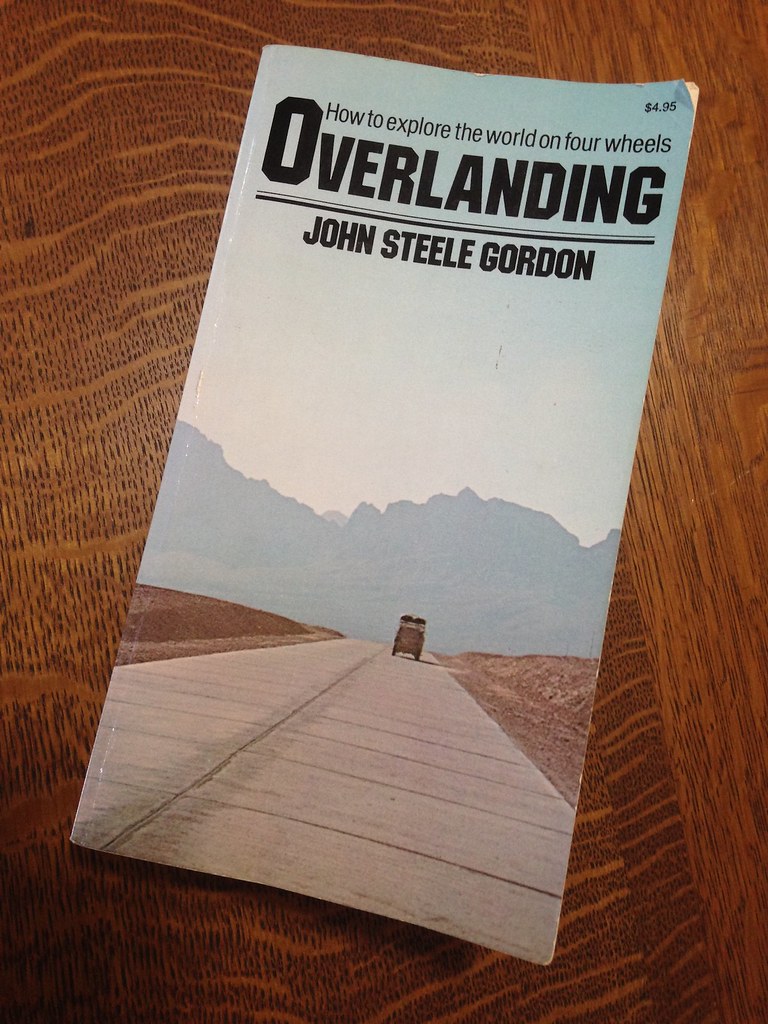

In the late 1970s, still a newish and decidedly rookie owner of an FJ40 Land Cruiser, I bought a book titled Overlanding, by John Steele Gordon. The author’s preface stated, “Overlanding is the landlubber’s equivalent of sailing: the long, slow crossing of large areas of the world.” The book was a complete guide to vehicle selection, equipment, border crossings, daily routine, and health for someone planning a long journey, and it fueled dreams that came true beyond what I dared imagine at the time.

Somewhere later on that book disappeared, loaned out and forgotten or who knows what. I always intended to search for a replacement. Then, at the 2015 Overland Expo East, I stopped by the headquarters tent to check on something, and a volunteer said, "Someone dropped this off for you."

I was thrilled and touched, more so because inside was a lovely inscription to both of us, and signed, “Jack Walter, Land Rover owner since 1972 and founder of Solaris, the Southern Land Rover Society.”

What a wonderful community we all share.

The new Tacoma's rear brakes are . . .

What, more whining about Toyota?

Well, yes. But before you start sending hate mail excoriating me for what’s beginning to seem like continuous criticism of the company, please keep in mind: My first car was a 1971 Toyota Corolla with the little 1600 hemi engine, which I modified to the point that it regularly snacked on BMW 2002s and Datsun 240Zs up Mt. Lemmon Highway in 1:00 a.m. dares. I’ve owned a 1973 FJ40 Land Cruiser for 37 years. Roseann and I have owned four Toyota trucks and two Land Cruiser station wagons. And I have sold uncounted Toyotas through recommendations and reviews. I have extremely high regard for the company.

However, that high regard includes high expectations. Karl Ludvigsen titled his encyclopedic history of Porsche Excellence was Expected, and that’s what I expect from Toyota. When I see a company with the engineering might (and profitability) of Toyota coasting on its reputation—and, worse, trying to tell us that cut-rate features are actually “better,” I have to call them on it.

The latest issue concerns the rear brakes on the redesigned 2016 Tacoma—Toyota’s mainstay truck in the U.S. and a powerhouse in sales. (The Tacoma accounts for between 50 and 65 percent of all mid-size truck sales; the Tundra a dismal five percent of the full-size truck market.) I first saw the new Tacoma in May at Overland Expo West, where the company had a sneak preview of the 2016 truck in the Four Wheel Camper booth (complete with camper). I liked a lot of what I saw. The interior, particularly, seemed more of a piece than that of our 2012. The new 3.5-liter V6 seemed poised to better the 4.0’s power and fuel economy. There were rumors of increased body rigidity due to the use of high-strength steel. Crawl Control and Multi-terrain Select would bring LR4 levels of off-pavement capability to the truck. All very promising.

There was one detail I wanted to check (besides the frame, already whined about here). Our 2012 Tacoma came with rear drum brakes—a cheap holdover even at the time, when the Nissan Frontier, for example, had boasted standard four-wheel discs as early as 2008 (as does our 2004 F350). I headed to the back of the new truck and peered through the wheel slots—and saw a cast iron brake drum.

I was floored. But I thought, optimistically, Okay, maybe this is still a prototype mule, equipped with some current features that will be updated for production. Surely?

No such luck: The 2016 Tacoma comes with ventilated front disc and rear drum brakes (as does the new Hilux!). But there’s more. When asked by reviewers—presumably as incredulous as I—why the commitment to a century-old brake design on a truck advertised as “Raising the bar—again,” Toyota’s response was, not making this up, “Drum brakes are better off road.”

The Toyota engineering rep claimed that the only advantage to rear discs—which, he admitted, are more resistant to heat-related fade—is for “heavy towing.” (Note here to you potential mid-size truck customers looking to tow your boat or loaded adventure trailer—or, for that matter, carry a camper: Toyota just implied you should shop elsewhere.) The engineer further claimed that drum brakes expose less of the mechanism to road grit, and are less susceptible to vibration from heat-related warping—this latter referring to brake disc warpage caused by overheating, which can create a shudder felt through the pedal when stopping.

Let’s look at these claims. First, Toyota says that discs aren’t necessary in the rear because rear brakes are less susceptible to heat fade than front brakes. The latter is absolutely true. Thus, by their own logic, the statement that rear drums are preferred to forestall possible heat-related vibration makes exactly zero sense, since they already told us that rear brakes are less likely to overheat in the first place. This specious argument would be better used to justify front drum brakes. If you’re having a problem with warping front brake discs, you need to redesign your front brakes, not put drum brakes in back to “reduce vibration.” And if you’re having issues with overheating front brakes, wouldn’t you want the best brakes possible on the rear?

Second, the claim that drum brakes are better sealed against debris, for example mud, is actually valid—to a point. Since the brake drum wraps around the shoes, temporary immersion in goop is less likely to let any inside. Disc brakes, on the other hand, can start squealing quickly when dunked in mud (So, again—why not drums in front too, Toyota?). However, once goop impacts itself inside a drum brake, it’s way harder to get out. Ask me how I know. A disc, on the other hand, will quickly clear itself. And were we talking about moisture? Ever driven a vehicle with drum brakes on all four wheels through a stream, then tried them on a downhill section a bit farther on? I remember the first time I did so with my all-drum 1973 FJ40: There were no brakes. It took 20 yards of frantic pumping before the water cooked out of those shoes and I got a faint sense of deceleration. That FJ40 now has discs on all four wheels. If you drive a truck with rear drums through water, your braking will be compromised until they dry out. Any claim that rear drums are “better off road” must either ignore or excuse reduced braking effectiveness after water crossings.

Above: A representative photo of a drum brake. This one happens to be on a Ford Model T . . .

And what about on-road driving, which, let’s be honest, comprises 90 percent of even the most adventurous driver’s mileage? Say, a long, twisting descent off a mountain? In such conditions your front brakes are providing between 60 and 70 percent of your braking force—which means that a minimum of a third of the work is being handled by the rear brakes. If those brakes are drums, which the builder of your truck has admitted are more susceptible to fade than disc brakes, well, again, your braking is compromised.

How about maintenance? Anyone who’s serviced both knows that disc brakes are easier to work on, and far easier to check for wear.

Are there any incontestible advantages to rear drum brakes? Sure, and you know the answer: cost. And the rear axle is where the vehicle’s parking brake is located. A drum brake does excellent double duty as a parking brake; a disc must usually have a small auxiliary drum to perform parking duties, further adding to the expense.

Does this sound alarmist? Am I predicting sure death for anyone stupid enough to buy a truck with rear drum brakes? Of course not. Nevertheless, brakes are the number one safety item on your vehicle. And disc brakes are superior to drum brakes, period. If Toyota wants to continue to economize on this feature in the face of all its competition, fine. Sell us on other features. But don’t try to tell us drum brakes are better. That insults the intelligence of legions of loyal owners, including this one.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.