Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Shackles: Are yours doing their job?

Proper shackle angle on an Old Man Emu suspension

I wonder if Obadiah Elliot had any clue, when in 1804 he patented a system of stacked steel plates designed to smooth the ride of a carriage, that his invention would still be in use two centuries later.

To be sure, the leaf spring has been eclipsed in sophistication by coil, torsion, and air springs, yet its simplicity, ruggedness, and low cost keep it standard equipment on the rear axles of millions of pickups and four-wheel-drive vehicles, as well as on the axles of larger freight-hauling trucks.

It’s not so much the cost of the spring itself that makes leaf-spring suspension systems cheaper to manufacture—it has to do more with the fact that a leaf spring also comprises its own locating mechanism. A coil or air-sprung beam axle requires a leading or trailing arm (or multiples) to secure it fore and aft, and a transverse arm such as a Panhard rod to locate it side to side. The leaf spring does both all on its own. Additionally, the stress a leaf spring applies to the chassis is divided between its front and rear mounting points, while the perch of a coil spring has to take all the load, requiring sufficient reinforcement.

Perhaps the biggest disadvantage of the leaf spring—that is, in the common configuration with multiple leaves—is inter-leaf friction, which not only hinders springing action but can vary or increase as, for example, the leaves become rusty. Some manufacturers such as Old Man Emu address this with a nylon pad at the end of each leaf, which can be lubricated.

There’s one situation, incidentally, when that interleaf friction can be an advantage—if you blow a shock absorber (as we recently did on our Land Cruiser Troopy), inter-leaf friction attenuates the endless cycling (bouncing) that would otherwise occur. If you’ve ever driven a coil-sprung vehicle with bad (or no) shocks, you’ll know what I mean.

Those of you with leaf springs at one or both ends of your vehicle likely have never given much thought to the shackles—those brackets that connect the free end of the spring to the chassis. But they perform a critical function, and their orientation can affect several aspects of suspension performance.

A leaf spring in its static position has a specified eye-to-eye length. When it flexes as the vehicle travels over a bump or through a hole, the spring “lengthens” or “shortens”—obviously it actually does neither; as it flexes the arch in the spring simply decreases or increases, changing the eye-to-eye distance. A leaf spring attached rigidly to the chassis at both ends could not flex at all, so the shackle travels through an arc to allow this. Clearly, then, you want the shackle oriented so it does this job as effectively as possible.

Take a look at this diagram.

Ignore for a moment everything but the angle at which the shackle meets the spring at the eye. This shows that angle as 90 degrees to the datum line—a line drawn straight between the eyes of the spring. For most practical purposes we can think of this as essentially right angles to the spring itself—an easy orientation to ascertain visually.

The most obvious and important result of this angle is that it lets the spring flex to its maximum extent both when compressed and extended. You can see that if the shackle were angled as in “A,” the spring could flex a lot downward (as the shackle pivots forward), but when compressed, the shackle would quickly bind against the chassis. Exactly the opposite is the case with the shackle at “B.” The spring has plenty of travel when compressed, but very little when extended. Another danger of a shackle angled as at “B” is that if the spring flexes too much the shackle can invert and lock itself against the chassis, completely immobilizing the spring.

You might also read or hear that the angle of the shackle can affect the ride quality of the spring—and this is where things get vague.

Note that this diagram claims that a shackle oriented at “A” will stiffen the ride while a shackle at “B” will soften it. I could find no explanation as to the physics of this supposed effect. On the other hand, I found a source claiming exactly the opposite. This one noted that with the shackle at “B,” when the spring compresses the shackle has to travel slightly downward in its arc before rising to the rear, and this jacks the chassis slightly upward, exacerbating the effect of a bump. Makes sense.

Not finished, however. Yet another fellow, with experience setting up racing vehicles, argues adamantly that the shackle has no effect either way on ride quality unless it actually binds. He points out that no matter what, the force from the spring is virtually straight up and down at the axle; the slight fore and aft movement imparted from the pivoting shackle is indiscernable. (He uses this fact also to argue against shackle-reversal kits as a waste of money.)

While the ride question remains unresolved, there’s no doubt that proper a 90-degree shackle angle allows the spring to do its job through the maximum possible travel in both compression and extension.

Look at the opening photo, which shows the rear of my FJ40 and its Old Man Emu suspension. The shackle angle is, as one would expect from the company, spot on (the front is as well).

In contrast, look at the shackle angle on the front springs of our Troopy:

Much closer to “B” in the diagram, no? These springs were installed at a shop in Perth, Australia, after we took it in to have them diagnose a worrying clicking noise I could both hear and feel through the steering wheel, and which neither Graham Jackson nor I were able to diagnose in the field except to be pretty sure it was in the steering. But the shop diagnosed worn springs, so we let them replace both sides.

We picked up the vehicle the day before we were scheduled to containerize both our and Graham and Connie’s Troopy for shipping to Africa—and as I drove away from the shop the clicking was there as loud as ever. Some testy and hasty negotiating resulted in a refund of all our labor charges, but the springs stayed on. (After getting the vehicle home I disassembled the steering and found indeed that was where the noise was coming from—just loose bolts in the tilt mechanism.)

Examining the springs in Durban I realized they had too much arch, resulting in this poor shackle angle. Whatever you believe regarding shackle angle and ride quality, these springs also definitely ride more harshly then the previous set, so I’m on a mission to fix both issues.

The first and most obvious approach is to remove a leaf in the springs. This isn’t necessarily as simple as it sounds, because removing the wrong leaf could create stress risers in the remaining leaves and lead to breakage. (So-called “add-a-leaf” kits can do this as well.) However, it looked to me that removing the bottom leaf on these springs wouldn’t compromise the rest of the pack, and the bottom leaf was the only one not captured with a clamp (or rebound clip to give it its proper name). So I jacked up the front end, loosened the U-bolts, and pulled the bottom leaves.

Notice the near-total lack of a wear pattern on the tips of the leaves.

After tightening everything again, I took the Troopy for a drive to settle everything then examined the results. Note the shackle angle in the first Troopy photo, and compare it to the “after” photo below.

If you’re thinking, “I don’t see the slightest difference,” congratulations. I don’t see one either. Clearly those bottom leaves are doing nothing at all—at least when the vehicle is static. They probably don’t provide any resistance until the spring is significantly compressed.

Since this is in no way an existential threat, I’m re-evaluating. I might still try removing another leaf, or I might just live with it for now—I certainly don’t intend to spring for new springs just yet . . .

The ARB Pure View 800 flashlight . . . up to standard?

Anyone who has read my equipment reviews over the last 15 years knows I’m a loyal fan of the ARB line of products. My FJ40 Land Cruiser has worn Old Man Emu suspension and IPF driving lamps for at least a couple of decades, and more lately has an ARB locking rear diff and High Output compressor, plus a branded fridge—and I replaced the IPF lamps with ARB’s superb Intensity LED units. Our Tacoma has an ARB winch bumper and rear diff. The Land Cruiser Troopy we recently shipped to the U.S. from Africa is fairly bristling with ARB equipment, from the front bumper and Intensity driving lamps to the ARB Twin compressor and more.

Rather incredibly—or perhaps not—not a single one of those items has ever failed.

Even though I’m lucky enough to have been sponsored for much of this later equipment, my respect for ARB’s products came about through a straight retail relationship. The first OME suspension I installed on the FJ40 cost significantly more than those offered by other makers, but the company’s reputation convinced me it would be worth the extra cash, and that indeed proved to be the case, as it was with the then-state-of-the-art halogen IPF lamps. Every ARB product since has thoroughly proved its value-for-money to me before I recommended it to others. Still, someone who simply chanced on all our vehicles lined up could be excused for thinking I’m a secretly paid shill for the company.

Now, however, I have in front of me the new ARB Pure View 800 flashlight, which I’ve been using for a month or so. And for the first time, my reaction to an ARB product is basically a shrug of the shoulders. Not that it is by any means a bad flashlight; it simply breaks no real new ground and includes no genuinely outstanding features (well, one, which I’ll get to).

The 800 refers to the flashlight’s maximum output of 800 lumens—an astounding figure just five years ago, but today merely good (and no doubt accurate—many of the claims you see for cheap internet flashlights are wildly exaggerated). The pattern is just about perfect—a penetrating central spot with an even cone of more diffuse illumination surrounding it. Clicking (or half-pressing) the large rear “tactical” switch again gets you a 400-lumen beam, another step goes to 200, and another to a strobe. Running time is claimed, in order, as “up to” 1.5, 4, 7, and 24 hours (although why one would want to leave a strobe on for 24 hours is beyond me). These strike me as no more than ordinary run times despite the chunky body of the Pure View and its lithium-ion battery. But at least it’s rechargeable.

I also have an issue with the circuitry in the switch. When you turn the light off for more than a few seconds, it reverts to the highest setting rather than staying where you left it. So if you turn it off on low in your tent before going to sleep, then turn it on in the middle of the night for a toilet excursion, you and any tent-mate will be blinded by the 800-lumen beam. I’d rather have the option of choosing my own setting. Additionally, I do not recall ever using a strobe function on any of the three thousand flashlights my wife claims I have owned (it’s no more than two thousand). I would have much preferred a 10 or 15-lumen low beam suitable for reading or walking around, one that would have then had a run time measured in hundreds of hours. The 200-lumen “low” setting is far too bright for reading or looking at a map, or even most camp chores.

The Pure View charges via a micro-USB port cleverly hidden behind a rotating collar, which keeps it dust-free and dispenses with the usual rubber plug that inevitably breaks. Nice. However, when charging you must remember to turn on the flashlight before plugging it in, at which point the lamp goes off and a red “charging” light surrounds the charging port until a green “charged” light replaces it. If you forget to turn on the light, you’ll get a false green “charged” light but the light will not in fact be either charged or charging. Charging time is slow—four to five hours, limited by the capacity of the micro USB—yet ARB warns not to exceed six, so you should not simply leave the light plugged in overnight to charge. Incidentally, that outstanding feature I mentioned? It’s the included charging cord—a red-and-black fabric-wrapped cable of superb sturdiness and style. I’m actually considering ordering spares for my other micro-USB appliances. (The included belt holster is also excellent.)

Just as I was becoming concerned that I might be being too hard on the Pure View, I was walking along with it dangling by the lanyard when one end of the lanyard pulled free of its plug and the flashlight whacked to the ground (with no damage). But really?

Don’t get me wrong—the Pure View is a fine flashlight I’ll be happy to keep around. And—importantly—it’s priced very competitively at $57, with a two-year warranty (one year on the battery). But, unlike so many of ARB’s other products, it does not stand out from a crowded field. And until the company adds a true low-power setting (an easy modification, I suspect) I wouldn’t recommend it as one’s only all-around flashlight.

The hazards of touch-screen ubiquity

Have you ever read the results of some study that probably cost tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to conduct, and thought, Someone paid money for this? Such as the one I read about some time ago, which showed that drivers of expensive cars were less likely to yield to pedestrians and bicyclists than drivers of older or cheaper cars. Wow, never could have figured that out on my own.

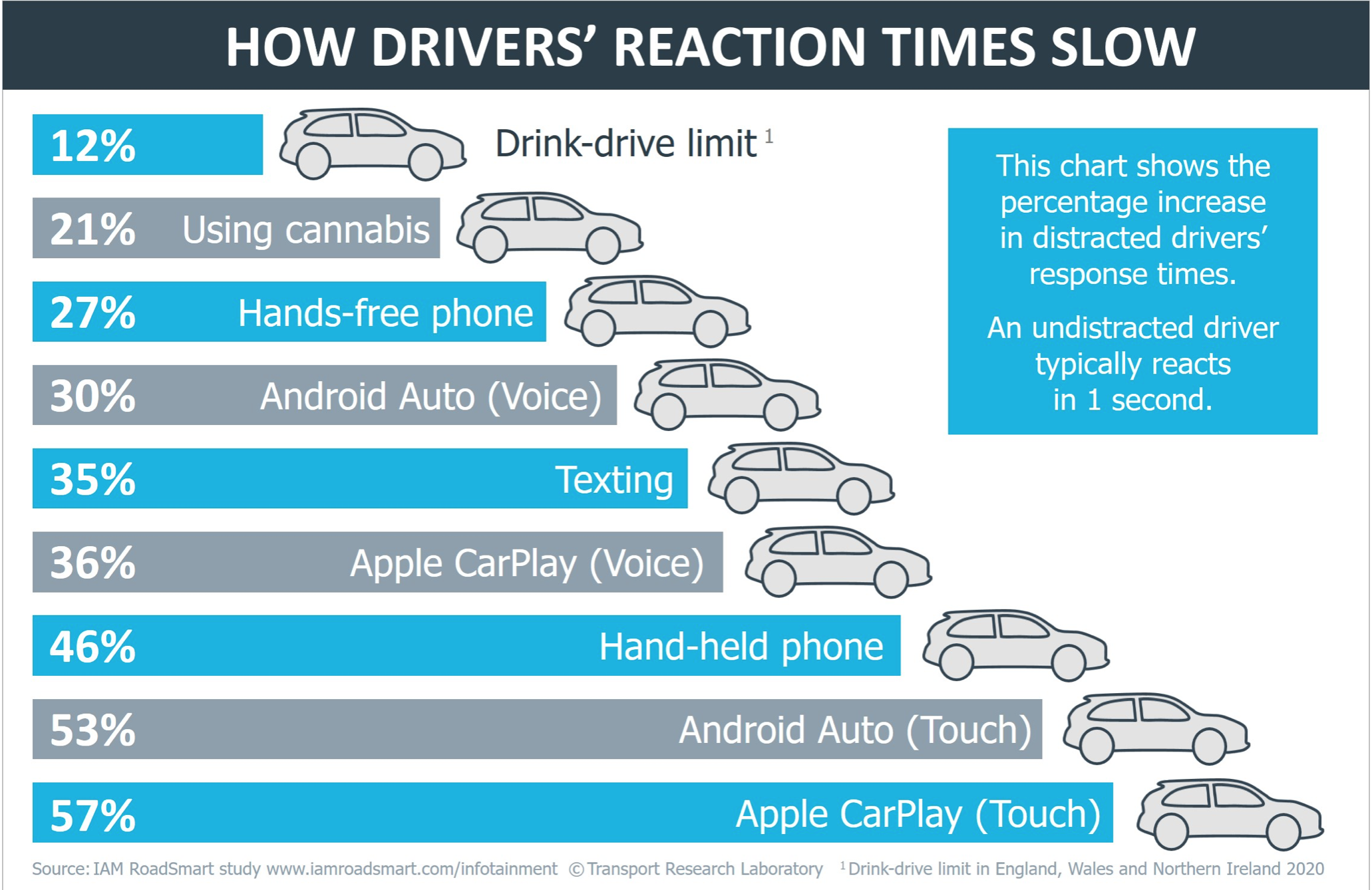

The latest is one run by the UK’s largest independent road-safety charity, IAM RoadSmart, which reveals that in-car touch-screen infotainment systems such Apple CarPlay and Android Auto drastically slow the reaction times of drivers. Stopping distances, lane control, and response to external stimuli all suffered even in comparison with texting.

Someone paid money for this?

Think back—those of you who can think back this far—to when the radio in your vehicle had two knobs and four or five manual station preset buttons. My FJ40 came with such a unit. To operate it I never had to take my eyes off the road. I could reach down and feel the on/off/volume knob, and tactilely count with a finger which station button I wanted to press.

Not so with the—rather ironically named when you think about it—touch screen. There is no way to tactilely determine where you are on a touch screen; you have to look at it. Combine that with the multiple functions and choices necessary to wade through and, well, as IAM RoadSmarts tests revealed, reaction times of tested drivers were worse than for those on cannabis and at the legal alcohol limit. Some drivers took their eyes off the road for as long as 16 seconds—that’s 500 yards at 70 miles per hour. Reaction times while choosing music through Spotify on Android Auto or Apple CarPlay were worse than for drivers who were texting.

It should be obvious by extrapolation that any operation controlled by touch screen—climate control, navigation, etc.—would have the same deleterious effect on reaction time. This, not any Luddite obtuseness, is why I strongly prefer mechanical controls for such accessories.

Incidentally, the same study showed that reaction times while using voice control for Android Auto and Apple CarPlay were also slower, albeit by not as much. Simply put, anything that takes your mind off driving is bad for your driving.

If you’d like to send me money for this revelatory post, email me for my Paypal address.

Once more, with feeling: Drum brakes are not "better off road."

It never fails to surprise me how persistent myths can be, even when there is an abundance of authoritative evidence to counter them.

A recent, otherwise informative and enjoyable article in a magazine I receive highlighted a classic four-wheel-drive vehicle from the 1960s. In describing the mechanicals, the writer noted that the brakes were drums on all four corners—still perfectly common in those years (my 1973 FJ40 came with all-drum brakes). While acknowledging this as outdated technology, the writer nevertheless went on to say (I’m paraphrasing), that drum brakes are less susceptible to loading up with debris off road, and that they stay cooler than disc brakes.

These claims are, respectively, badly misleading and utterly wrong.

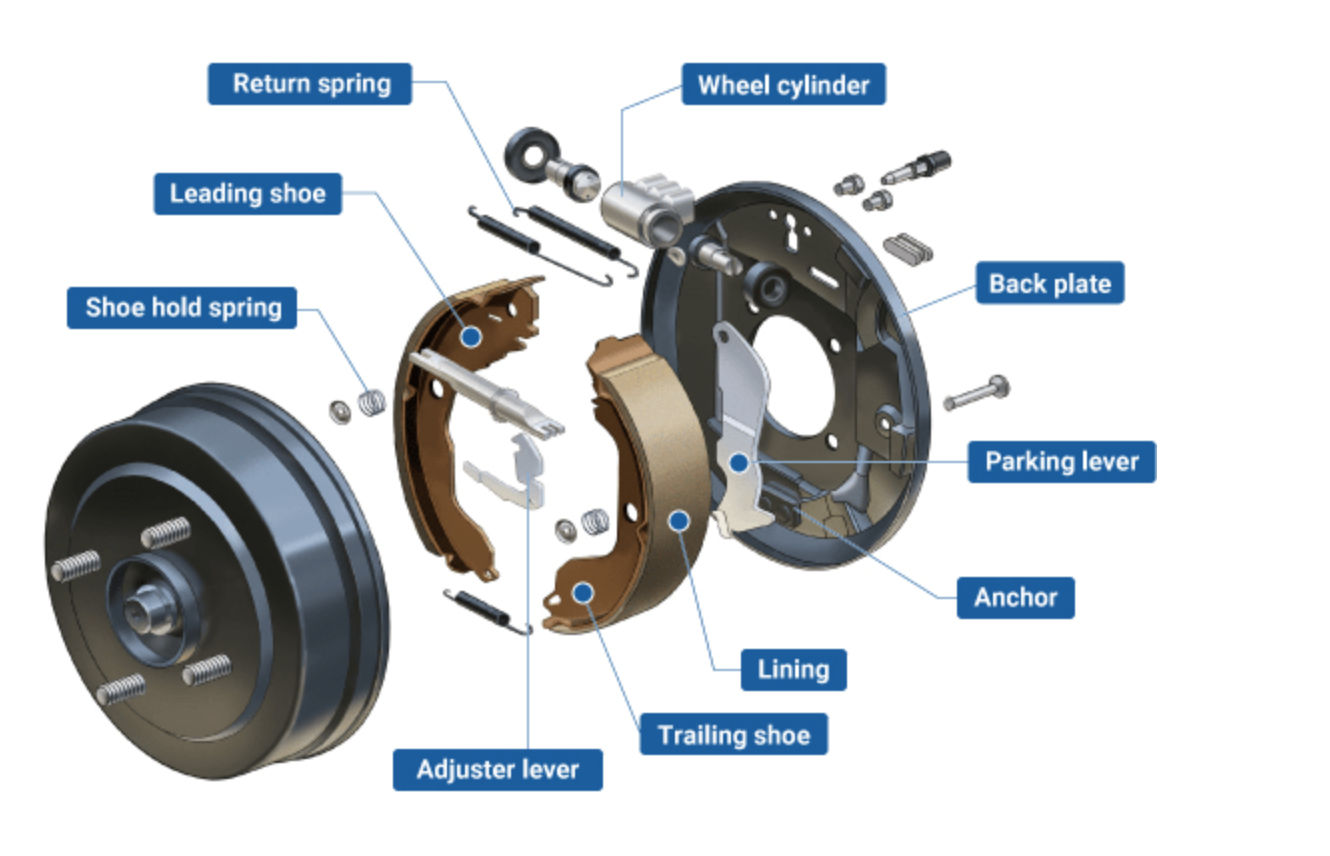

The claim that drum brakes are less likely to load up with debris—for example mud during an excursion through a mucky hole—might seem logical on the surface, since a disc brake’s rotor is completely exposed to the elements and is immediately doused with whatever comes its way. It is more difficult for gunk to work its way past a drum-brake’s backing plate and get into the mechanism. (No less an entity than Toyota Motor Corporation co-opted this line to excuse its parsimonious decision to retain rear drum brakes in the current Tacoma.)

The problem is that, once that gunk does get into a drum brake’s internals—and it will—it stays there until you disassemble it and clean it out, a time-consuming chore. Ask me how I know. A disc brake might squeal initially as slush impacts against the pad and disc, but it will quickly wipe itself clean, and if there is anything left a quick powerwash will take care of it. Drum brake shoes ride farther away from their contact surface on the drum, allowing debris to be caught between them.

The other claim, that drum brakes stay cooler than disc brakes, blithely ignores basic physics. Stopping a moving vehicle requires converting its kinetic energy into thermal energy. Period. All brake systems, whether drums or discs, have to absorb and then dissipate the exact same amount of heat when stopping an equivalent vehicle from an equivalent speed. Period. And while drum brakes absorb heat just fine—my FJ40, which now has four-wheel-disc brakes, stops no shorter than when it had all drums the first time you do so—they are are significantly worse at dissipating the heat they have absorbed. On a long, winding downhill road towing the 21-foot sloop I owned at the time the 40 still had stock brakes, the pedal would get progressively softer and less effective as brake fluid boiled into gas at the system’s wheel cylinders, where the drum brakes were retaining huge amounts of heat. Converting to disc brakes solved the issue as their rotors, exposed to the air, more rapidly dumped that heat.

So, once more, with feeling: Drum brakes are not “better off road.”

The big question: roof tent or ground tent?

The sleek but expensive Autohome Columbus in carbon fiber

Of all the requests for advice I receive, only choosing a vehicle seems to create more angst than the question of whether to buy a roof tent or a ground tent.

In simple economic terms this makes sense, since—especially if you decide on a roof tent—the outlay will likely be second only to the vehicle in terms of the hit on your overlanding budget. In fact I know people who have accomplished major journeys in vehicles that cost less than several roof tent models I can name.

But it’s also an important “lifestyle” choice, if you will, since carrying, deploying, and living with and in a ground tent is an entirely different proposition than doing so with a roof tent—even a roof tent with an add-on ground-floor room (or “mullet,” as a friend nicknamed the dangling appendage). So let’s look at the pros and cons of each.

Cost. Easy win for the ground tent here. The least expensive, made-in-China, soft-shell roof tents nudge $1,000. Premier products from Eezi-Awn, Tepui, iKamper, and others frequently top $3,000. And the size medium carbon-fiber hard-shell Columbus from Autohome will set you back a palpitation-inducing $5,600. By contrast, a 10’x10’, made-in-the-U.S. Springbar Traveler ground tent, one of the finest portable cabins on earth, costs $950. The 8’x8’ Turbo Tent Pine Deluxe 4 (from China), one of my favorite standing-headroom ground tents, is $495. And if you’re on a budget and don’t need standing headroom, there are dozens of options starting at under $200 from companies such as Slumberjack and Sierra Designs.

Classic, comfortable, and durable: the Springbar

Weight. Another win for the ground tent—with a couple of footnotes. That $5,600 carbon-fiber Autohome Columbus still weighs 92 pounds—and you’ll need a roof rack sturdy enough to support that weight while in motion and another 250-300 pounds when occupied. The soft-shell Front Runner “Featherlight” weighs 88 pounds. Larger and more feature-laden soft- and hard-shell roof tents typically weigh between 150 and 200 pounds. On the other hand, the 10’x10’ Springbar ground tent, made from substantial canvas and supported by substantial poles, weighs 62 pounds including poles and stakes. The 8’x8’ Pine Deluxe Turbo Tent weighs 42 pounds. Many other ground tents with as much interior volume as a large roof tent weigh less than 15 pounds. It’s true that roof tent weight includes a mattress, but that’s a matter of, at most, ten pounds.

The footnotes? Obviously the 62 pounds of the Springbar, or even the 42 pounds of the Pine Deluxe 4, is weight you’ll have to wrestle every time you pitch it—not so with a tent attached to the roof. Mount it once and forget it (unless you need to remove it between trips, either for handling and fuel economy or to avoid looking like an OVERLANDER every time you go grocery shopping). Importantly, the added weight of the roof tent is positioned in the worst possible place to add weight. Trust me that a 150-pound roof tent on an 80-pound roof rack will result in a noticeable difference in the on-road handling of even a substantial vehicle, and will make side slopes on trails more interesting.

Room. A runaway win for the ground tent. Even the most humongous roof tent is no larger than a good-sized backpacking tent. There are no roof tents with standing headroom for anyone taller than a four-year-old. Even a “mullet” only adds what is essentially a changing room. By contrast that Springbar Traveler will accommodate two full-size cots, plus a table and chairs or two smaller kid’s beds. You say you’re six foot five? You’ll still be able to stand up inside. The Pine Deluxe 4 is actually even taller at the peak.

In inclement weather, when you might be stuck inside during daylight hours, the contrast is even sharper (unless you’ve masochistically confined your ground tent to a backpacking model). Inside the 100 square feet of the Springbar you can walk around, sit across from your tentmate at a table to play cards or work, or catnap. Your luggage is out of the way under your cot. Cooking inside is easy. You can warm the space with a portable propane heater.

A Pine Deluxe 6 Turbo Tent, 10 feet square

Pitching. This is not as simple a question as it seems. Ground tents are intrinsically more involved to pitch, given unpacking and unfolding them, staking, running guylines, installing a fly, assembling cots or inflating mattresses, etc. Some are faster than others—the canopy of the Turbo Tent, for example, with its integral frame structure and spring-loaded joints, goes up in a flat minute. But you still need to add the fly and stakes. The Oz Tent is hyped for its rapid pitch, but it still requires stakes and guylines too. I got the pitching time for a Springbar down to a leisurely 15 minutes solo, or 10 with help.

Roof tents are universally marketed for their simple and rapid pitch, and for some models this is so. Hard-shell clam-shell models (hinged at the front), for example, are absurdly easy to deploy: You simply undo the latch(es) and hydraulic struts raise the roof. Done in five seconds. Some hard-shell box-style tents have the same system. Closing is just as simple and quick.

Soft-shell roof tents, however, vary widely in ease of deploying and, especially, stowing. The transit cover can be easy or difficult to remove before deploying the hinged floor and watching the canopy bloom. Window awnings need spring struts installed from inside, and if you’ve added a changing room you essentially have a ground tent to deal with as well, which must be attached to the frame of the tent at the top and staked out at the bottom. But it’s the process of stowing a soft-shell tent—and especially re-installing the transit cover—that can be the most time-consuming. I’ve done a lot of cursing while trying the stretch Velcroed covers back over several models I’ve reviewed. Nevertheless, on balance a ground tent will most likely take more time to pitch and stow than a roof tent.

A Technitop soft-shell roof tent with annex (or “mullet”)

Wind and precipitation resistance. This is more a function of the individual model rather than the type. A roof tent, of course, has the advantage of being bolted to a two or three-ton ground anchor, so there’s scant chance of it blowing away. And hard-shell roof tents, both the clam-shell and box style, tend to be superbly wind resistant. Soft-shell roof tents, on the other hand, can be okay or really bad. I’ve seen few that have adequately strong supports for the window and door awnings, and in general rain flies tend to be very poorly secured and prone to maddening flapping. Whether or not the tent itself is wind-resistant, it’s perched atop a vehicle with suspension and acts as an effective sail, so boat-like rocking can be a factor in getting a peaceful night’s sleep.

Any ground tent must be staked to be secure, and if possible I stake out guylines as well—I’ve never experienced a tent that was too wind-resistant. Staking can be problematic if not virtually impossible in several substrates: sand, mud, or slickrock, for example. The Springbar is the only big ground tent I’ve ever tried that comes with adequate stakes. Buy big ones; you won’t be sorry.

I’ve slept in roof tents that leaked and in ground tents that leaked, so again this is more a function of quality control than one style or the other.

You can’t beat the space in a ground tent

Sleeping comfort and bedding storage. Unless you suffer from claustrophobia, as my wife does (she once nearly knifed her way out of a smallish clam-shell tent after a midnight attack), actual comfort could be considered a tossup. Most roof tents come with thick, comfortable mattresses, on which you can use sleeping bags or standard bedding and pillows—which in many models can also be stored inside. Ventilation is generally excellent, and you’re up where breezes are unhindered and more free from dust than at ground level.

For any ground tent you must separately arrange (and store) cots or mattresses plus sleeping bags. With that said, a good cot topped with a thick Thermarest and a flannel-lined sleeping bag provides one of the most transcendent sleeps on the planet—right up there with being partway to the sky in a roof tent, like a kid in a tree fort. Take your pick. (One P.S.: With cots as your beds, it’s much easier to sleep outside on clear nights than it is to extract the mattress from a roof tent.)

Fuel economy/cargo space. Even the sleekest hard-shell roof tent will add significant aerodynamic drag, and with one of the big soft-shell designs on your rack you might as well be towing a drogue parachute. Clearly a ground tent stored inside the vehicle presents no such issues—but then a big ground tent might take up so much space you’ll be tempted to strap other gear to a roof rack. Win to the ground tent as long as you can avoid a roof load.

Other trade-offs. A roof tent is nice if the substrate is muddy, when a ground tent would wind up slimy outside and possibly in. Climb the ladder to the roof tent, remove your muddy shoes and store them in the pocket provided for just that purpose on many models, and your little home stays spic and span. On the other hand (you knew there’d be one), if the ground is muddy it means it’s been raining and is likely to rain more, and we’ve already discussed how much nicer it is to be holed up in a spacious ground tent. Take your pick.

In some situations, a ground tent can be left in place to reserve your campsite while you go exploring in the vehicle. A roof tent obviously needs to be put away completely to do so.

Rather counterintuitively, leveling the tent is easier when it’s attached to the vehicle, as you can use blocks or even rocks under the tires. A ground tent needs actual level ground. Also it’s usually easier to reorient a vehicle and roof tent than it is a staked and guyed ground tent, to account for shifting breezes.

A ground tent is way easier to move between vehicles, or to loan out to a friend.

Much has been made of the safety factor of a roof tent in regions with large mammalian predators, especially Africa. Honestly, after quite a few nights spent in both roof and ground tents on the continent, I find this a weak argument. Predators very, very rarely mess with tents, much less try to gain entrance. Yes, I’ve seen the YouTube video of the lions pawing at the ground tent, but I’ve also seen the one of the elephant disassembling the roof tent. Either is an extremely unlikely situation. And if you’re worried about creepy crawly things like snakes sliding into your ground tent and cozying up to you in the middle of the night, keep the door zipped shut.

So there you have it, and I’m sure there are other arguments for each. If you’re already a fan of one or the other you’ll find it easy to count up enough arguments in your favor. Otherwise, perhaps this list will help tip you one way or the other, depending on your own priorities.

Those Southern Ocean breezes . . .

What happens if you leave a 70-Series Land Cruiser exposed to the onshore Southern Ocean wind on the southwest coast of Tasmania, for 25 years or so? This . . . spotted in Trial Harbor.

Part Souq, an international resource for parts

Whenever possible I try to buy parts for our vehicles locally. For the newer ones this is generally no problem, but automobile dealers seem to be increasingly reluctant to stock parts for any model more than a few years old. And when you begin your conversation with the counter person with, “I have a 1973 . . .” he looks at you like you just stepped out of a time machine. (It would be fun to run with this some time, and as he’s looking futilely at his screen for spark plugs to fit a 46-year-old FJ40, say something like, “So, do you think Nixon will resign?”)

If parts for the 40 flummox the dealer, imagine the situation with a 1993 HZJ75 Troopy that was never even officially imported into the U.S. I don’t even try.

Fortunately there are several specialty Land Cruiser shops around the country that carry at least the commonly needed items for 70-Series Land Cruisers, and a few have surprisingly extensive inventories. In part this is due to the happy fact of a model that has changed very little over its 35-year history. Cruiser Outfitters and cruiserparts.net are good sources.

However, even these enthusiast outlets can’t carry everything. And supposing you’re looking for something really arcane—like say, a Toyota factory floor mat in “sable,” the brown that is our interior color?

Some time ago I was introduced to an online parts source called PartSouq.com—“souq” being the Arab term for a market. (Amazon, I understand, recently bought the English/Arabic-language E-commerce site souq.com; I have no idea if the two are related.) I called up the site, clicked on the Toyota section (the site lists 20 brands and claims 17 million parts in its database). A prompt asked me for the VIN of the Troopy, so I retrieved that, typed it in, hit enter—and was rewarded with a complete catalog of parts for a 1993 Toyota Land Cruiser HZJ75. Engine, transmission, chassis, electrical, body—it was all there, with diagrams. I went to the interior section, hovered over the floor mat part number, 58510B (when you do this, the list on the side scrolls automatically to the correct placement), and clicked on that. It showed four factory floor mats available, three in gray, one in sable. The sable mat was located in . . . Oman? Yep. “Ships in one day,” it said.

Needless to say, clicking “Buy now” on a $310 item located halfway around the world took a leap of faith. Only the rave reviews I’d read of the site gave me the courage to do so. Shipping was nearly a hundred dollars—hardly unexpected.

What was unexpected was finding the large box containing our new Toyota factory HZJ75 floor mat, in sable, at our commercial mail service four days later. The mat was perfect, and a welcome replacement for the sadly (and hazardously) chewed-up original.

So if you can buy your parts locally, please do so to support your nearby economy. But if you can’t find it close, and the factory made it, there’s a really good chance it will show up on a PartSouq.com search.

Curiously useful: the offset box wrench

I never owned a set of offset box wrenches until last year. The configuration always seemed like something that could be duplicated by other tools—a standard combination wrench, even a ratchet and socket. It seemed like a solution to a problem that didn’t exist—even though I had noticed them in the tool chests of several professional mechanic friends.

But then I chanced across a beautiful German-made set from Stahlwille (say “stallvilla”) on sale online—and few things can make me reconsider the need for a tool faster than a discount price on German-made version of that tool. Since I had some birthday funds available from my wife, I ordered the set, which comprised eight tools that covered the broad and useful span of 7 to 22 mm. They were as beautiful in person as in the photos. I set them up on a wrench rack in my rolling chest and more or less forgot about them.

But over the past few months, a funny thing has happened. I’ve found more and more situations for which an offset box wrench was the perfect tool, indeed just a bit more convenient or secure than whatever I would have used before. Sometimes it was just nice to have the extra knuckle clearance provided by the offset design.

And twice already I’ve used one in circumstances where no other tool I owned would fit. The latest involved snugging the nylock nuts on the rear engine mounts on the FJ40, which had loosened a bit as the new motor mounts installed when the engine was rebuilt have compressed a tiny bit. The driver’s side bolt head is easily accessed on top of the mount, but the bottom 19mm nut is inside the boxed chassis rail, accessible only through an opening about three inches in diameter. That by itself might not have been a problem, but I have a header on my engine, and the exhaust runs very close to that hole.

I tried a socket and ratchet. No go. Short extension on it? Nope. Just a breaker bar on the socket? Close, but not quite. Standard combination wrench? Uh uh.

Hmm . . . I grabbed the 17/19mm offset box wrench, angled it into the hole above the exhaust, and bink. It snapped right on.

So my who-needs-them? offset box wrenches have become some of my favorite tools. Of course you really don’t need the über German versions—unless you’ve got some birthday cash on hand.

Just in case, Stahlwille is available here.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.