Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

The one-case tool kit, part 4

(Please read part 1 here, part 2 here, and part 3 here)

I've finally wrapped up my project to assemble a comprehensive one-case field tool kit—and I’m really glad I restricted myself to a Pelican 1550.

It’s absolutely axiomatic when assembling a tool kit that it will expand to fit the available space, and it would have been effortless to fill a much larger container with Oh-I-should-have-this items, to the point where any notion of portability went out the window. As it is, the case and contents had nudged above 55 pounds by the time I was satisfied.

But after over a year of playing stump-the-tool-kit, I have yet to come across a task the contents couldn’t handle. It’s been employed successfully for jobs ranging from repairing a Honda generator in Mexico’s Sierra Madre (used, critically, to power UV lights for an insect survey) to replacing the dreaded trap oxidizer on our old Mercedes 300D at home (which incidentally resulted in a good 20 percent power increase). One fiendishly positioned nut on that device eventually required the Snap-on 18-inch ratchet, two extensions, a universal joint, and a socket to access—all there in the case. The closest I came to being stymied was removing the 10mm allen-head bolts on a Porsche 911SC anti-roll bar. The swiveling allen key in the kit baaarely got those loose; I’ve decided to add a set of 1/2-inch-drive allen-head sockets, which will take up scant room.

So: What’s in it? Here is the complete list (see previous installments for the justification for each):

- Britool 748267 3/8ths-inch socket/ratchet set (1/4” to 1” SAE sockets; 6mm to 24mm metric sockets, Torx sockets T8 to T16, assorted driver bits)

- Facom S.200 DP 1/2-inch socket/ratchet set (10mm to 32mm metric sockets)

- Snap-on SX80A 18-inch flex-head ratchet

- 1 1/2-pound sledge-head hammer

- Craftsman replaceable-head soft-faced hammer

- Combination wrenches (7mm to 25mm plus 27 and 30)

- Facom torque converter

- Facom Pro-Twist Shock screwdriver set

- Assorted Craftsman screwdrivers including stubbies

- Snap-on replaceable-bit ratcheting driver

- Brass drift

- Three cold chisels

- Two punches

- Small pry bar

- Knipex and Channel-Lock pliers

- Two pairs needle-nosed pliers

- Vise-Grip pliers

- Small self-adjusting plier

- Side cutter

- Electrical stripping/crimping tool

- Hemostats

- Six-inch adjustable wrench

- Three snap-ring pliers

- Adjustable hacksaw

- Combination flat/half-round file

- Round file

- Tin snips

- Two LED flashlights

- Box cutter

- Spark-plug puller

- Radiator-hose pick

- Feeler gauges

- Power Probe voltage/resistance tester

- Continuity tester

- Swiveling hex-key set

- Small wire brush

- Mechanic’s gloves

- Tube of hand cleaner

- Safety glasses

So—while the selection is meager compared to what I have available in the rollaway chest in the shop, even I, who had high hopes, have been surprised at how effective it is. Yes, if I need a hammer at home I can choose among nine or ten to get exactly the right weight and head, while in the case I must make do with two—but so far I’ve been able to make do nicely.

Believe it or not, there’s a bit of room left over in the Pelican. If I were to embark on a really long journey, I could still fit in, say, a hand drill and bits, a pickle fork to separate ball joints, a hub socket to fit the Land Cruiser, and a couple other more obscure items.

I don’t consider this selection definitive. I have absolutely no doubt that sooner or later I’ll run into a situation I can’t handle (although I’d allow myself a pass on true special tools required for certain specific tasks on many vehicles). But for now I’m convinced I have put together a pretty good one-case tool kit. Is it "The Ultimate One-case Tool Kit?" I guess that's open to a challenge . . .

At the Overland Expo, May 17-19 2013, I'll be demonstrating the one-case tool kit for Overland Experience package holders on Friday at 2:00 PM and Saturday at 4:00 PM. Overland Experience attendees can also attend my class on assembling a basic tool kit, Friday at 1:00 PM and Saturday at 3:00 PM. Find out more about the Overland Expo HERE.

Irreducible imperfection: the SOL Origin

Manufacturing miniature survival kits must be the closest thing to printing your own money short of selling bottled water. I’ve looked at dozens of them, and rarely found contents worth more than about $2.95—usually some fish hooks and monofilament, a few feet of cheap paracord, matches or friction fire starter, a button compass, and a couple of safety pins. Maybe a tiny mirror for signaling. For a while many of them came with a condom, the stated purpose of which was not to provide safe sex with that drooling grizzly bear loping in your direction, but to carry water. Right.

I’ve recently been evaluating the SOL Origin survival kit, which retails for around $40, and I must say the contents of this kit are a step up from some. In fact, I’d say there’s a good six or seven bucks worth of stuff in here.

SOL stands for Survive Outdoors Longer (as well as the banal double entendre). SOL is a division of the parent company that owns Adventure Medical Kits, which I’ll say up front produces some of the very finest expedition first-aid kits, one of which is standard equipment on all our African projects.

The SOL Origin comprises an ABS plastic case enclosing the following:

- Three square feet of aluminum foil—sorry, heavy-duty aluminum foil according to SOL

- A combination knife, LED flashlight, and whistle

- A liquid-filled button compass

- A “Fire Lite” thumb-wheel fire striker

- Four #10 fish hooks

- Fishing line

- Six feet of .020” stainless-steel wire

- Signal mirror

- Two snap swivels

- Two split-shot line weights

- Four pieces of braided “Tinder Quick”

- Sewing needle

- Ten feet of 150-pound-test braided nylon cord

Okay—maybe I was wrong about the six or seven bucks worth of contents. Let’s make it five.

So, what do we have here? I’ll start with the palm-sized case, which for some strange reason comes with a wrist lanyard, as though that’s how you’d carry it around ready for deployment the instant you felt disoriented. The case is constructed in such a way that the knife/flashlight/whistle, the fire striker, and the button compass slide into slots on the outside. This accomplishes several nifty things at once. It increases the chance one or more of those items (the most critical in the kit) will be damaged or come loose and be lost; it severely reduces the internal volume of the case, rendering it unusable for, say, scooping water out of a crevice or digging; and it makes the device look much more tactical, meaning the maker can charge more than if they gave you a simple metal box that could also be used for cooking or boiling water.

You hope they don't come out of their own volition. The LED bulb is visible at the base of the knife blade; whistle on the other end. Battery compartment is under the "SOL" lettering.

You hope they don't come out of their own volition. The LED bulb is visible at the base of the knife blade; whistle on the other end. Battery compartment is under the "SOL" lettering.

The button compass is simple, well-dampened, and seems to work just fine. Since most people who become lost know more or less in which cardinal direction civilization (or at least the road) lies, it could be a useful tool. There’s a little thumbnail slot in it to facilitate removing it from the case; if this had been pushed through all the way you’d have the option of hanging the compass around your neck on a cord. You could easily drill it out.

The knife blade is 1 3/4 inches long, made from actually-not-bad AUS-8 stainless steel, and is quite sharp. It opens with a right-handed thumb stud, and even locks with a simple Walker liner lock—at least, it’s supposed to. I found that light finger pressure easily overpowered the lock. Best to pretend it’s not there rather than count on it to prevent getting cut. The blade flexes back and forth rather alarmingly on its pivot. The knife would be perfectly functional for gutting a trout or making feather sticks to start a fire, but for anything beyond that—building a shelter, for example—it’s worthless (and I think many so-called survival knives are far too large). The tiny LED flashlight casts a decent keychain-light-level glow and is supposed to shine for 15 hours. There is room in the case for a spare pair of button batteries (which you’d have to buy on your own). But the battery compartment is secured with a tiny Phillips-head screw, so unless you have the means to remove that . . .

The flashlight bulb shines along the axis of the knife, which sort of helps you see what you’re cutting, but it’s not nearly as effective—or as bright—as a separate flashlight would be, even one powered by a single AA battery.

The whistle opposite the knife blade is loud. Just don’t get distracted if you spot a would-be rescuer while whittling a tent peg or something, and stick the wrong end in your mouth.

Lit - finally - but not much of a flame.

Lit - finally - but not much of a flame.

Next is the fire striker, to be used in conjunction with the four, inch-long bits of braided tinder inside, which appear to be infused with paraffin or something similar. Since, in many if not most survival scenarios, fire is your single most vital survival and signaling (not to mention psychological) tool, one would expect care to be taken here. The striker is said to produce up to 5,000 sparks, but—and this is assuming the thing hasn’t come out of its slot and disappeared—the sparks it generates are nothing like the shower produced by a proper ferrocerium stick. I tried it on one of the pieces of tinder, and it took me two minutes of repeated striking to finally get the cord lit, after which it burned with the strength of a large candle for a bit over two minutes, showing very little resistance to the light breeze that was blowing at the time. I literally used up a hundred or more of those 5,000 sparks to light a manufactured bit of tinder. I wouldn’t even try it on natural tinder. Could the cord have dried out during the time this kit sat on a shelf? Not good if so.

Last on the exterior list is the polycarbonate signal mirror, which hinges off the lid and thus at least can’t be lost easily. The aiming hole in the center of the mirror incorporates retro-reflective mesh, a material that allows extremely accurate aiming. The fold-out “survival pamphlet” in the case includes clear instructions on how to use it—which is lucky, because the graphic under the mirror is utterly incomprehensible. Nevertheless, the mirror is adequately sized and bright, protected from scratching, and undoubtedly the best implement in the kit.

The signal mirror is a good one, but don't try to figure out how to use it from the graphic.

The signal mirror is a good one, but don't try to figure out how to use it from the graphic.

On to the inside contents. First, the “three square feet” of “heavy-duty” aluminum foil. At 5.5 by 11.5 inches, their math is a bit off, at least for the piece in my kit. My arithmetic comes up with slightly less than half a square foot. Second, I’ve encountered heavier foil wrapped around a stick of Juicy Fruit—this piece came pre-holed on one of the folds. Finally, even the makers seem unsure what to do with the stuff. The pamphlet says, under “Improvisation,” that it “can be used as a reflective device for signaling.” Isn’t the mirror better for that? Another suggested use is as “ . . . a head covering when the night comes on cold.” Okaaaay. So I tried it. I felt like a stick of Juicy Fruit.

The author, contemplating actually facing the wilderness with this stuff.

The author, contemplating actually facing the wilderness with this stuff.

Onward. Ten feet of braided nylon is perhaps enough to string between two trees to support a poncho or Space Blanket for a shelter. Or you could lash your 1 3/4-inch SOL knife to a stick and go hunting for . . . well . . . chipmunks, perhaps. Or meadowlarks. Twenty feet would have been better, and 20 feet of 550 paracord even better.

Safety pins. Three of them. I want to know: HAS ANYONE IN RECORDED HISTORY EVER NEEDED A SAFETY PIN IN A SURVIVAL SITUATION?

A sewing needle. So you can keep your survival duds neatly mended, or suture the gashes you sustained when that grizzly bear tried to . . . never mind.

Four #10 fish hooks, snap swivels, split shot, and monofilament line. A fine addition to the kit, given the right circumstances of course. In fact, I would have preferred more hooks in different sizes, and more line. The company’s site doesn’t specify the test of the included line, but it appears to be more than adequate for the hook size. It’s up to you to figure out out to crimp the split shot on the line. It’s also up to you to know the proper fisherman’s knot that will secure the slippery monofilament line to the snap swivels; the pamphlet includes none.

Six feet of snare wire (okay, they call it “safety wire,” but the pamphlet suggests using it for snaring). Another fine idea in theory. With a bit of training—and as with the fish hooks, the right habitat—snaring small mammals is a viable survival technique that requires minimal materials and minimal energy expenditure. However, the wire in the SOL Origin was so completely useless for this purpose as to be laughable if the company weren’t touting it as a life-saving device. It was so springy that even after concerted effort I could not straighten it enough to form a stable loop, yet it also kinked horribly. Finally, while holding one end down with a boot and pulling on the other end to try to straighten it, the wire simply snapped at one of the kinks. Not good. Even if the wire were suitable, you need multiple snares to ensure success, and six feet is not enough.

The worthless- and broken - "safety wire" from the SOL Origin in the middle, with a professionally made wire snare capable of taking small game.

The worthless- and broken - "safety wire" from the SOL Origin in the middle, with a professionally made wire snare capable of taking small game.

Thankfully, that was the last item in the kit, because by this point I was shaking my head in disbelief that the SOL Origin had ever reached the market in this form.

Let’s stop to postulate here. You’re lost in the wilderness. You have no vehicle, no means of communication. Depending on environmental conditions, the next 48 hours will determine whether you live or die. Do you really want to pin your future on a two-inch knife, a plastic spark generator, and some Reynolds Wrap?

Oddly, the kit’s pamphlet (written by Buck Tilton, who should know what he’s talking about, and who calls this “the best little survival kit in the world”) properly identifies survival priorities: positive attitude, medical care, shelter/fire, signaling, water, and food. The SOL Origin fails to address medical care and water at all (not even a few iodine tablets included), is marginal at best on food (worthless snare wire and adequate fishing supplies), and is poor on fire/shelter (build a lean-to with that knife?). Daytime signaling is the only facet that achieves good marks.

I’d even give it a fail on engendering a positive attitude. Given that up to half or more of your time spent lost is going to be at night, with all the attendant practical and psychological implications, the failure to include a proper flashlight is a strong hint that this kit was designed by a designer, not anyone with experience in survival situations.

I could go on to rant about the pamphlet too, but I won’t. Okay, just one: Water. Buck tells us, among other gems, that “ants” mean water is not too far away. I can show Buck lots of ants that don’t live within 50 miles of water. Also, “Birds, especially grain-eating birds, fly to water at dawn and dusk.” Buck, the operative word there is “fly.” And finally he repeats the old saw about “digging at the bends of dry washes.” The only thing you’ll wind up with eleven months of the year if you try that where I live is a pre-excavated grave.

The concept of a palm-sized survival kit is interesting, and I suppose one could argue that the SOL kit is better than nothing at all. But it would be absurdly easy to put together a kit taking up little if any more space, which would be infinitely more useful for saving your life. Yes, it would cost more—if you don’t think your life is worth more than a nice lunch out, I have an SOL Origin I’ll part with for a pittance. As it is, if I somehow found myself caught out with this thing in a survival situation, my first thought would be:

Man, I am SOL.

Unfortunately, Buck won't be there when you need him.

Unfortunately, Buck won't be there when you need him.

Three days on El Camino del Diablo

Few places on earth have experienced such a completely circular human history as the desert traversed by southern Arizona’s El Camino del Diablo. In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries its harsh plains and jagged mountains comprised a gauntlet for missionaries, explorers, and seekers of gold traveling northwest from Caborca to the first sure water at the Colorado River. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries it became another gauntlet, this time for illegal immigrants from Mexico and Central America trekking north seeking the gold of employment in the U.S. The tally of deaths from either period is impossible to pin down, but likely very similar. Some say each is in the hundreds.

Yet like many landscapes that have witnessed human tragedy, the magnificence of this corner of the Sonoran Desert transcends the strivings and failings of the bipedal creatures that scratch its surface. Here is a region where temperatures in summer regularly exceed 115 degrees Fahrenheit, yet where biological diversity is higher than in the pine-clad Rocky Mountains. Here lives a species of fish—found in just one spring-fed pond—that can survive water temperatures of 95 degrees and salinity higher than the ocean. The bighorn sheep that look down from the cliffs can lose 30 percent of their body weight to dehydration and survive with no ill effects. Within multi-holed mounds on the desert floor is a small rodent, the kangaroo rat, that never drinks or even needs to eat moist vegetation. It manufactures its own water from the carbohydrates in the dry seeds that comprise its entire diet. When winter rains are plentiful—meaning a few inches—the desert floor explodes in spring with a show of wildflowers to rival any English meadow. And always, always, the open space gives new room to lungs constricted by city living, and sharper vision to eyes clouded by concrete horizons.

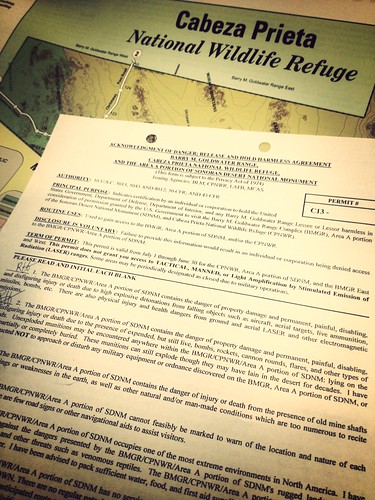

I first traversed "The Road of the Devil" in the sultry August of 1979, alone in my FJ40. In a week I saw not another soul—as far as I know, I had a million acres all to myself. That has changed, and although the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and the Barry Goldwater Air force Range, through which the road passes, remain remote and rugged, the U.S. Border Patrol now maintains a persistent presence, with two F.O.B.s (forward operating bases) plonked down surreally in the desert, and constant patrols. Before you can get a permit as a new visitor, you’re required to watch a 15-minute video and sign off on a hold-harmless form detailing at least 27 ways a stupid person could get hurt or be blown to smithereens in the area.

It’s worth it. The landscape along the main road from Ajo south and west through a corner of the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, across the Growler and Mohawk Valleys and the Tule Desert, is breathtaking, and changes with each pass through the mountain ranges—some dark, some light, some weirdly striped—that angle northwest/southeast through the refuge. The soft peach Pinta Sands dunes stand out in contrast to the surrounding lava fields, and improbable stretches of tightly overhanging mesquite trees mark the courses of washes that turn the road into impassible muck during summer thunderstorms.

The entire center section of the Camino is closed to public use from March 15 to July 15 to minimize disturbance to the secretive and endangered Sonoran pronghorn during fawning season—although the impact of the Border Patrol and migrants must be far greater than that of the few tourists who still brave the route. But if you wish, you can still drive in to the spectacular Tinajas Altas tanks from the west.

We beat the closure and spent a too-short weekend driving from Ajo to Tule Well, then north through Christmas Pass to Interstate 8. While some parts of the road are rough, and there are miles of corrugations north of Christmas Pass, we could have done the trip easily in a two-wheel-drive truck—or a sedan—in these conditions. West of Tule there are sections of bulldust that would challenge a low-clearance vehicle, however.

A four-wheel-drive Tacoma is almost overkill on El Camino. We're doing our best to abuse the stock street tires that came with the truck before mounting some all-terrain rubber.

A four-wheel-drive Tacoma is almost overkill on El Camino. We're doing our best to abuse the stock street tires that came with the truck before mounting some all-terrain rubber. Our first camp was at Papago Well, where a relief station and emergency beacon set up for migrants is marked with a blue flag.

Our first camp was at Papago Well, where a relief station and emergency beacon set up for migrants is marked with a blue flag.  Marisa stands amid the Pinacate lava flow, the northernmost extension of the Pinacate volcanic region. Near here is also the northernmost extension of the Altar dune field, called the Pinta Sands.

Marisa stands amid the Pinacate lava flow, the northernmost extension of the Pinacate volcanic region. Near here is also the northernmost extension of the Altar dune field, called the Pinta Sands. Looking down on Tule Well and the campsite (one of four on the refuge). The little cabin was built in 1989, replacing an earlier structure. A log book is inside for visitors to sign.

Looking down on Tule Well and the campsite (one of four on the refuge). The little cabin was built in 1989, replacing an earlier structure. A log book is inside for visitors to sign. Tule cabin is open and available for anyone to use if needed. There's even a small fireplace in the corner.

Tule cabin is open and available for anyone to use if needed. There's even a small fireplace in the corner.

Boy Scout troops erected this monument on the hill overlooking tule Well.

Boy Scout troops erected this monument on the hill overlooking tule Well.

Campfires are permitted, but you must bring your own wood. We also used a sturdy Snow Peak Pack & Carry fireplace.

Campfires are permitted, but you must bring your own wood. We also used a sturdy Snow Peak Pack & Carry fireplace. Dawn from Tule Camp. Mockingbirds and Phainopeplas were getting ready to breed, and singing.

Dawn from Tule Camp. Mockingbirds and Phainopeplas were getting ready to breed, and singing. Heading north through Christmas Pass, affording a fine view of our ultra-low-profile Global Solar photovoltaic panels, which provide the Four Wheel Camper with a surfeit of power.

Heading north through Christmas Pass, affording a fine view of our ultra-low-profile Global Solar photovoltaic panels, which provide the Four Wheel Camper with a surfeit of power. Under a cloudy sky we headed north toward I-8, past this enormous ironwood tree.

Under a cloudy sky we headed north toward I-8, past this enormous ironwood tree. Lots of unexploded ordnance on the Barry M. Goldwater range. This fin could be a piece, or there could be an entire missile under there. Do we pull on it?

Lots of unexploded ordnance on the Barry M. Goldwater range. This fin could be a piece, or there could be an entire missile under there. Do we pull on it? Federal law states that it illegal to visit the Cabeza Prieta without stopping at Dateland afterwards for a zillion-calorie date shake. Well, if it's not illegal, it should be. Support local business!

Federal law states that it illegal to visit the Cabeza Prieta without stopping at Dateland afterwards for a zillion-calorie date shake. Well, if it's not illegal, it should be. Support local business!

If you go: The refuge headquarters and visitors' center is in Ajo, on the road north out of (or into) town (Monday through Friday 8:00 to 4:00). You're required to obtain a free permit to enter the refuge, and will also need to register at a kiosk on the refuge border. The roads through the refuge are easily traversed, but a sturdy vehicle is recommended. You could drive the length in a day if you really wanted to, but it would be a wasted journey not to slow down and experience the scenery and wildlife.

Take plenty of water—there are no reliable sources on the refuge, and what's there is needed for wildlife. Take enough to ensure you could walk out to the nearest highway if necessary; don't count on a Border Patrol agent coming along to rescue you.

A fine book on the Camino del Diablo is Sunshot, by Bill Broyles.

View our entire collection of trip photos on Flickr, here, and our video highlights, below.

More good stuff from Lifeproof

I’m not as technologically averse as all my friends and family like to joke. In fact, I pioneered the switch to Mac computers in our household in 2003, and managed to learn the new operating system pretty much on my own. Digital cameras? I was all over them once the images reached publishable resolution.

However, I will admit to a fierce, abiding loathing for the telephone, or, to be specific, talking on the telephone. For me it’s always been a tool for dispensing or receiving important information as quickly as possible, not for leisurely chats. There are few phone conversations I can’t get through using artful combinations of “Yes,” and “No,” occasionally spiced with “Sure,” or “Probably not,” including calls home to my wife after two weeks incommunicado in Zambia. Any interchange that goes over 30 seconds and my fingers start tapping, my pupils dilate, and a high-pitched keening sound becomes noticeable to the person on the other end. The torture scene in Zero Dark Thirty? Calls from my mother were worse.

And that’s why—until recently—a $19 flip-phone was all the phone I needed. I’d point over the counter at the Verizon store and ask, “Can that one in the back make calls?” If the answer was, “Well, sure, but . . .”—sold.

Then telephones started doing more than annoying me, because they started doing more than ringing. First they added GPS—astonishing enough—but then came apps and Google Maps, and suddenly on road trips Roseann could tap her iPhone and find the best coffee or café in any town on our route in seconds. No more fishing down side streets, gambling on local diners, or settling for anodyne chains. The facility made road trips far more enjoyable, and probably saved enough time to add a hundred miles to the distance we could cover in a day.

There was more, such as the level and tilt app that allowed us to precisely measure the angles of slip faces on dunes in Egypt’s sand seas. And the utterly magic Star Walk, which recently informed us that the bright satellite passing over our camp in the desert at dusk was in fact the International Space Station. And the National Geographic North American Bird Guide, which includes a complete audio section on calls and songs.

So . . . sigh . . . after losing my most recent throwaway phone somewhere in Africa, I became the owner of an iPhone 5—and, not ten minutes after regaining normal heart rhythm from sticker shock, learned about accessories. I remember when the only accessory for a phone was the rubber banana-shaped thing you stuck to the handset so you could hold it with your shoulder. Not anymore.

First addition was a Lifeproof case. And a fine addition it was, considering that for the last decade I’ve been used to treating my $19 phone like . . . a $19 phone. No need to walk clear across the room to put it on my desk—a simple toss gets it there quicker. Not a good idea with a zillion-dollar miniature computer/phone/camera/GPS thing, but old habits die hard. So the shock-resistant, waterproof Lifeproof case gives me peace of mind. Furthermore, it vastly improves my grip on the phone, which when nude had an unsettling orange-seed squirtiness about it, like it could fly out of my grasp on its own. It necessitates a slightly firmer tap to use the touch-screen, but not much, and since I do not text, facile typing is unnecessary. I note that Roseann, who frequently answers business emails on her iPhone while I’m driving, doesn’t seem to have a problem.

Most recently we received one of Lifeproof’s suction-cup vehicle mounts. It can attach to the windshield, but the kit includes a disk with adhesive backing you can stick elsewhere on the dash if you don’t want the unit in your line of sight of the road. We attached the disk to the passenger side of the center console, clipped in the phone, and left for a weekend trip along southern Arizona’s Camino del Diablo, which sports miles and miles of punishing washboard (or corrugations as the rest of the world knows them), especially along the Christmas Pass exit road to I-8. The iPhone on its mount remained astoundingly vibration-free throughout the trip, and Roseann had no trouble tapping in navigation commands without the need to support the unit from behind. It’s a solid system, and well worth its $40. Of course it’s sized to take the iPhone only if it’s inside a Lifeproof case, and we’d need another model for Roseann’s slightly smaller iPhone 4S (it fits but not as securely). But I suspect if they made it one-size-fits-all the rigidity would suffer, so I won’t complain.

I recall how thrilled I was with our old Garmin 276 GPS and its bulky, jiggly windshield suction mount. Just five years later we have a device that does ten times more at a fifth the weight, and a mount that renders it as steady and accessible as if it were another dashboard gauge.

Isn’t technology wonderful?

Quality . . .

I learned the hard way that the best equipment—and thus frequently the most expensive—almost invariably costs the least in the long run.

I was eight or nine years old, and desperately craved a fishing rod and reel to use on a three-acre pond that existed improbably barely a mile from our house outside Tucson, Arizona. The pond was fed by Sabino Creek, and boasted a population of sunfish and largemouth bass—a miraculous opportunity for a desert kid addicted to magazines such as Field and Stream and Sports Afield, which seemed to focus almost entirely on bucolic Catskill trout streams and Minnesota lakes.

I had a job sweeping porches and cleaning the yards of empty new houses waiting to be sold in our sprawling rural neighborhood (50 cents per unit if memory serves), and was slowly saving for a beautiful Shakespeare open-face spinning reel and rod set on display at the Save-Co in town. Then my friend Bruce, always above me on the childhood income scale, showed up with a superb matched Mitchell/Garcia set. Rats, as we said then. Next trip to the store, the Shakespeare combination gleamed at me, still out of reach—but another set in a blister pack was priced exactly at the amount of cash I had, and half the figure on the Shakespeare tag. So I brought home a little push-button spincasting reel called a Compac BEARCAT and its five-foot fiberglass rod.

Sigh . . . Big mistake.

While Bruce’s Mitchell/Garcia reel and sturdy six-foot rod immediately went to work hauling in sunfish and bass for our pond-side campfire and Boy Scout frying pan, my pot-metal push-button alternative immediately went to work malfunctioning. A typical session would go like this: I wind up for a cast, flip the rod forward, and release the button to freespool the line. My lure zings away in an elegant arc toward the eagerly waiting fish—but then the spool cover of the reel detaches and flies off on its own tangent trajectory, taking a loop of line with it. This causes the lure to abruptly reverse its elegant arc and come whizzing back to embed itself in the tip guide of the rod with a thwack.

There were other issues with the reel, and within six months the rod had begun to delaminate and shed vicious little fiberglass splinters. I did manage to catch some fish with that miserable bit of equipment, but the fatal flaw in my impatient attempt at thrift jelled into a lesson that has stuck ever since. When I bought my first external-frame backpack a couple years later, I gritted my teeth and waited, ignored the cheapo stuff, and paid—what was it, $19.95?—for a Camp Trails pack and frame combination, which served yoeman’s duty for the next ten years until I switched to an internal-frame Gregory Snow Creek, again the top of the line at the time and again a faithful and durable piece of equipment—in fact I still have it and could easily rotate it back into use.

In the early 1980s I learned about a new outdoor equipment company called Marmot Mountain Works. They were pioneers in manufacturing Gore-Tex outerwear and sleeping bags, and produced only exceptional, U.S.-made gear—at wincingly exceptional prices*. Nevertheless, over the course of a couple of years I managed to invest in a Warm II Gore-Tex down parka, a bantamweight Gore-Tex goose-down sleeping bag called a Grouse, and an utterly bombproof three-hoop mountaineering tent called a Taku.

That was 30 years ago. I still have every one of those items, and still regularly use all but the tent (which is tight for a couple). The sleeping bag retains probably 90 percent of its original loft; the parka is still the warmest piece of clothing I own. (And that last bit brings up the other salient advantage to high-quality equipment: It doesn’t just last longer; it works better too. You don’t gain much even if your cheap gear lasts a long time if you have to put up with substandard performance in the meantime—you might find yourself wishing it would wear out.) My amortized cost for that parka and sleeping bag must be literally pennies per use.

Thus, despite a penurious career as a freelance writer, I’ve remained faithful to the Church of Good Equipment, whether it be fishing rods, vehicles, or anything in between. Very frequently this has meant waiting for things I wanted right now, or buying used when I wanted shiny and new, and it’s always meant choosing priorities rather than buying every expensive item that strikes my fancy like some Robb Report subscriber. I’m reminded of the clueless interviewer who asked fishing writer John Gierach how a guy with a leaky roof and a 20-year-old truck in need of a valve job could afford a collection of vintage split-cane fly rods. Gierach just looked at the guy and said, “Isn’t it obvious?” Whenever anyone hints that I have more money than I let on, I point to our own cottage in the desert, which encloses a full 350 square feet under its (non-leaking) roof. We have more cover for our vehicles and equipment than we do for ourselves. That’s my kind of prioritizing—fortunately I’m blessed with a wife who agrees.

We’re lucky—not everyone can make such clear-cut choices in today’s world. Raising a family, in particular, creates overreaching priorities that push all others to the rear. Nevertheless, no matter what your circumstances, I’ll always maintain that defaulting to higher quality will save you money—and potentially a lot of grief—in the long run.

Especially if you live near a bass pond.

*Sadly, not any more. Like so many other such makers (including Camp Trails and Gregory), Marmot was sold off by its founder and now produces products offshore. Much of it is still good stuff, but . . . not the same.

Proper backup lights for the JATAC - with remote control

Brilliant 19-watt Grote LED floodlamps are optional on the Four Wheel Camper. Could they serve a dual purpose?

Brilliant 19-watt Grote LED floodlamps are optional on the Four Wheel Camper. Could they serve a dual purpose?

The sealed-beam automotive headlamp was introduced in the U.S. in 1939. In 1940, the government embraced the technology and required every car sold in this country to be equipped with identical 7-inch diameter incandescent headlamps—and for the next four decades, time essentially stood still. Not until 1978 did the U.S. legalize the superior halogen design (which had been used in Europe since the 1960s). Only in the last 15 years have further real advances been made in automotive headlamp technology, first with HID units and now, increasingly, with LED designs.

Rather peculiarly, though, our reversing lamps still appear to be stuck in 1940.

While a few manufacturers have begun installing LED backup bulbs, most remain incandescent. None that I’ve seen of either type matches the output of an average cheap single-AA LED flashlight—and this is with an entire automotive electrical system available to power it.

The situation is bad enough when you’re in a sedan trying to back out of a dark driveway without running over a pedestrian. It’s much, much worse if you find yourself too far down a narrow, rough four-wheel-drive route at night and need to turn around without going into the cactus or, somewhat worse, over the 50-foot cliff on the other side. I’m convinced not one Toyota, Land Rover, Jeep, or Mercedes engineer has ever been out testing a vehicle in the dark and found the need to engage reverse. Time after time in such a situation I’ve found myself trying to ride the brakes while doing so, because the brake lights are significantly brighter than the lights that are supposed to be showing me the way.

On my 1973 FJ40 I addressed the deficiency by installing a 50-watt Cibiè halogen fog lamp on the rear swing-away. Bam—problem solved. I can now reverse confidently out of a dicey situation without fear of making things worse.

Nice LED brake lights on the Tacoma . . .

Nice LED brake lights on the Tacoma . . .

Our 2012 Tacoma’s running light and brake bulbs are all efficient, durable, and bright LEDs. (The brake lights add a safety factor: LED’s activate about two-tenths of a second faster than incandescent bulbs. If that doesn’t seem like much, consider that at 40 mph the car following you will travel 12 feet in that time, which could easily mean the difference between a non-event or a neck brace.)

Where was I? Right: The Tacoma’s reversing lights. I knew from experience they were . . . adequate, but didn’t work any better than the ones on our 2000 Tacoma. I couldn’t see what type they were by looking through the faceted lens, so I pulled the lamp assembly and the bulb, and, yep . . . 1940. What gives, Toyota?

But what's with the cheap reversing bulb?

But what's with the cheap reversing bulb?

Ordinarily I would have gone online to look for upgraded bulbs, either a higher-wattage halogen replacement or an an LED conversion, although even this approach is somewhat limited by the stock reflector and lens. Other options include LED strips that mount on the license-plate frame (there are even compact HID reversing-bulb kits available with the potential to melt the plastic housing of the tail-lamp assembly).

However, since we have a Four Wheel Camper on our truck, and since on that camper we ticked the option box for a pair of high-mounted Grote 19-watt LED flood lamps that light up an area behind us most easily measured in acres, an obvious solution presented itself. Thanks to a tip from another FWC owner, Michael Doyle, I ordered a Cyron RC2-12 remote switch kit off Amazon for $25. The kit includes two key-chain remotes and a control box just a couple inches on a side, and advertises a 100-foot range.

Given the low draw of the LED floodlamps and the protected location, I simply crimped the connections rather than soldering them.

Given the low draw of the LED floodlamps and the protected location, I simply crimped the connections rather than soldering them.

I pulled the switch assembly for the floodlamps and simply Siamesed the power and delivery-side wires of the remote into the existing wires to and from the manual switch. Another wire from the control unit went to an existing ground screw in the battery compartment behind the switches, and the unit itself attached to another existing screw. Voilà—we can now create reversing daylight from the driver’s seat anytime we need it.

(I know what you’re thinking, and yes: This would be a formidable weapon against tailgaters. In fact I fear it would be too formidable. The sudden appearance of lights this blinding could very well send said tailgater off the road—or into oncoming traffic. Tempting though . . .)

The Cyron remote can be used to switch any number of things, and can, for example, obviate the need to run switch wiring into the cab for driving lights. However, for high-amp loads you’d want to connect it through a relay rather than directly.*

The compact control unit attached to an existing screw inside the camper's battery compartment. Grey wire on top is the antenna.

The compact control unit attached to an existing screw inside the camper's battery compartment. Grey wire on top is the antenna.

I’m still envisioning the perfect reversing lamp setup for a four-wheel-drive vehicle. Imagine a two-way system, with a properly bright light for urban driving and a switch that would activate extra-bright LED bulbs for use in the field. Sort of like the old city/country horn switch on the Jensen Interceptor of the 1970s, which activated a polite “toot” for urban use and an “out of my way” air blast for the country.

Of course, it’s unknown whether anyone actually bothered to ever switch to the city horn mode. So c’mon, someone just give us some good stock reversing lamps . . .

*This year at the Overland Expo, Baja Designs will conduct a demonstration on current lighting systems, covering the latest advances in HID and LED technology.

The Red Oxx Lil Roy

Recently Jim Markel, the CEO of Red Oxx (and son of the founder), contacted me to ask if I’d like to review something from his company’s line of heavy-duty luggage.

I was already familiar with their fine, U.S.-made Sherpa duffels, which, unlike many competitors, employ a rectangular box design that maximizes every cubic inch of space in the back of a vehicle or the cargo compartment of a bush plane. I asked what he might have that I hadn’t seen, and he mentioned a small tote called the Lil Roy. It sounded useful, so I asked him to send one.

He sent five. And after casting about to find uses for them, I’m glad he did.

Think of all the small items you typically carry in a vehicle that could use extra protection, organization, or just visibility. A quick glance around our FJ60 before a recent trip to Mexico’s Sierra Madre, where we’re surveying mammal populations using automatic trail cameras, revealed a bunch of potential applications. There was a pair of handheld two-meter radios we use to stay in touch on the area’s mountainous trails; Roseann’s Swarovski and my Leica binoculars—both armored and tough, but worth about a zillion dollars each and thus nice to keep cased when possible—several field guides; the remote for the winch (kept in the center console and always tangling in other stuff); the trail cameras themselves, and several other odds and ends.

Like all Red Oxx products, the Lil Roy is made in Billings, Montana. You won’t find any fatuous tags reading, “Designed with pride in America.” (Translation: “Assembled by small children in an Asian sweatshop.”) The only items the company has made outside the U.S. are the clever little “monkey fist” zipper pulls, which are tied in a small village in Guatemala, where Red Oxx built a workshop with a bathroom, shower, and cooking facilities, and recently granted a microloan to build a corn-grinding mill. Fair enough.

Although the Lil Roy is a compact nine by three by six inches (175 cubic inches), it’s sewn from the same 1,000-denier Cordura as their largest duffels. The #10 YKK toothed zipper looks comically large on a bag this small, but it’s stronger than an equivalently sized coil zipper, and more resistant to jamming from debris. Inside, there’s not an exposed fabric edge in sight—everything is taped and double-stitched. Flat mesh pockets on each side are useful for incidentals. For example, we have a 911SC with a compact spare you have to inflate in the event of a flat; I’m using one Lil Roy to hold the small compressor I carry for the purpose, plus the non-marring socket designed to prevent scratching the black paint on the Porsche’s fancy aluminum lug nuts. (Aluminum? Yes, really.)

Outside, the Lil Roy’s web handles wrap under the bag and, given the modest volume of this thing, would probably support it filled with material from the core of a neutron star. The self-locking zipper pulls are unlikely to come undone accidentally, but just in case, Red Oxx supplies a little steel cable with a screw fastener to keep them together. The metal dog tag on it, stamped with the company name and product information, could easily be replaced with another tag stamped with personal information. If not needed to lock the zippers it simply hangs off one of the handles.

Criticisms? Frankly, none that I could come up with. I don’t think the bag gains anything by having the zipper wrap so far down the sides, but that’s inconsequential. It’s not remotely waterproof, but it wasn’t intended to be. I’d like to see the Lil Roy offered in an additional version (Big Roy?) the same length and height, but twice the width—I’m thinking tire chains, jumper cables, like that.

The biggest surprise of the Lil Roy is its $25 price. I don’t know how they can produce something of this quality in the U.S. for so little. The Lil Roy is available in 12 colors; I think most of us could find a use for every one.

The Red Oxx website is here.

The one-case tool kit, part 3

(Part 1 is here, and part 2 is here)

(Part 1 is here, and part 2 is here)

It’s been drilled into us from the first time we picked up a toy hammer to tap a square block into a square hole: Use the right tool for the job.

The tool that most frequently falls afoul of this axiom is without doubt the slotted screwdriver. It’s been drafted into double duty as a paint-can opener, a scraper, a chisel, a punch, a pry bar, and worse by, I’m willing to bet, every single person reading this. Millions of them have been blunted into uselessness for their primary function after years of abuse in secondary roles.

So the hard and fast rule for field repairs is never to risk the function of one’s screwdrivers by employing them for non-approved secondary tasks. The tool kit should incorporate cold chisels for chiseling, punches for punching, and a scraper for scraping.

However—frequently one will come across screws that have seized into place, and which no amount of torque on a standard screwdriver will budge. The normal procedure in a home shop would be to break out the impact driver—a fat grip with an angled anvil inside which, when provided with a bit to fit the stuck screw and given a sharp whack with a hammer, imparts a sharp loosening impact and twist to the fastener. My impact driver has saved me much time and grief when working on older vehicles.

The problem is that an impact driver is a heavy and bulky thing for its single purpose, making it troublesome for a traveling tool kit. But there’s a little-known fact regarding impact drivers: the vertical impact on the fastener has as much to do with freeing it as the twist the driver provides. Therefore, if you simply hold a standard screwdriver against a stuck screw and give it a whack, the odds are good it will be sufficient to do the job.

But there we are abusing the screwdriver again. Furthermore, most screwdrivers have plastic handles, which are not only likely to shatter when struck, they also absorb enough of the hammer’s impact to blunt its effect on the screw.

Enter the Facom Protwist “Shock” screwdriver. Here’s a screwdriver with a specially hardened steel shank that extends all the way through the handle to a cap on its end. The company says the tool is designed to “withstand gentle impact to free stuck fasteners.” That’s right: You’re actually invited to whack this screwdriver with a hammer (within reason, obviously).

Neat feature, but after all the need for it rarely occurs, especially if the average age of the vehicles in your fleet is younger than the three-decade average of ours. Fortunately the Protwist screwdrivers are excellent at normal screwdriving tasks as well. Each one has a fat, ergonomically secure and grippy handle—unlike the frightfully expensive set of Snap-on screwdrivers I invested in 20 years ago, which had miserable, slick, hard plastic handles and wound up relegated to duty as spares within months. The Facom AWCK.J5 set (don’t ask me how they come up with these designations) comprises the five most-used configurations—a number 1 and 2 Phillips and three slotted heads, 8, 6.5, and 4mm. All but the 4mm driver have hex fittings so you can apply a wrench for greater torque, another good method for tackling a recalcitrant screw (as long as the screwdriver fits the screw head properly). The Phillips and slotted tools are differentiated by yellow and red caps and the appropriate icon for easy identification when stored handle-out in a tool roll (and each has a little “wear your safety glasses” silhouette as well—pay attention).

Unfortunately I couldn’t find a U.S. source for the Protwist “Shock” screwdrivers. But a supplier in England, Primetools.co.uk, carries them and has good prices plus fast trans-Atlantic shipping.

Alternatives? If you don’t need the hammerable feature, the standard Sears Craftsman sets such as this one are hard to beat for 20 bucks, although they also lack the wrench-compatible hex fitting, which leaves you no way to augment the torque you can apply to the screw short of clamping a pair of pliers to the handle, which is kinda rude. Better is this Kobalt 12-piece set I found at Lowe’s. These do have the wrench fitting, and the set includes two offset screwdrivers—wretched little tools that will nevertheless sometimes winkle out a screw no other driver can get to.

While we’re on the subject of removing stubborn stuff . . . I consider a hacksaw to be a must-have item in a comprehensive tool kit. And in case you’re thinking by this point I’m a helpless sucker for obscure and expensive tools, the best traveling hacksaw I’ve found cost me $6.99 at Ace Hardware.

I started out with a fancy aluminum-framed item that caught my eye when I was first musing on the idea of a one-case tool kit. Hey, aluminum—lightweight. Perfect, right? Not so much, at least not this one. First, it was bulky and took up way more room than its expected frequency of use justified. It also only accepted a 12-inch blade. Worse, use revealed a serious design flaw I should have noticed at first glance.

Which is better, the $30 hacksaw or the $6.99 hacksaw?

Which is better, the $30 hacksaw or the $6.99 hacksaw?

Any framed hacksaw will only let you cut things as thick as the clearance between the blade and the spine of the saw, unless you can move the saw around and cut from the other side. My aluminum-framed saw had a fine four inches of clearance—but only in one spot thanks to the arched spine. So when cutting through, say, a 3.5-inch-thick tube, by the time I got near the other side my cutting stroke was reduced to about one inch. Stupid.

Grooves on the left accommodate different blade sizes, and by filing the groove on the right . . .

Grooves on the left accommodate different blade sizes, and by filing the groove on the right . . .

Then, while browsing at the Ace I found a simple, steel-framed hacksaw, which proved to weigh less than the aluminum one and was far more compact. Grooves on the adjustable half of the spine engage a through-pin on the fixed part to allow the use of different-length blades; furthermore, by filing a third groove near the front of the solid section I can now remove the blade and make the saw collapse to just 13 inches in length, so it fits along the short side of the Pelican case and takes up scant space. I store the blades in the tool roll that holds screwdrivers. It’s single downside is that the blade can only be attached vertically; the aluminum model can also hold the blade at 45 degrees for cutting when overhead clearance is reduced.

. . . the saw collapses to fit almost unnoticed along the side of the Pelican case.Now—back to obscure and expensive tools.

. . . the saw collapses to fit almost unnoticed along the side of the Pelican case.Now—back to obscure and expensive tools.

If you’re ever faced with a major repair in the field—replacing a clutch, halfshaft, differential, or birfield for example—you’ll also be faced with the manufacturer’s torque specifications when it’s time to put everything back together. Sure, you can guess and bodge it, and I’ve done so many times without catastrophic consequences when home and the torque wrench weren’t more than a few hundred miles away. But if you’re in the middle of a major trip you don’t want to risk the repair and perhaps the trip by over- or under-torquing a fastener on a critical component (such as, say, the main bearing caps on a crankshaft . . .).

The problem is, a torque wrench is a long and bulky thing that performs exactly one function—you do not want to use it as a standard ratchet or breaker bar. So how about a palm-sized tool that turns any 1/2-inch ratchet into a torque wrench? That describes the Facom torque adapter—but wait, there’s more. The Facom unit also functions as an angle indicator. Many newer vehicles (Land Rover especially comes to mind as an early adopter) employ “angle-controlled” fasteners, designed to be tightened a certain number of degrees beyond snug. The Facom torque/angle adapter will do both tasks. It comes in a number of ranges; mine functions to 200NM (150 pound-feet, selectable on the readout) of torque, and is accurate to within three percent.

I have to say I found much less expensive torque adapters via a quick Google search, but none that were as compact, or that were capable of both torque and angle measurements. When Roseann asked, “Well, how much did it cost?” I answered:

“What lovely weather we’re having.”

Next: The rest of the kit: Will it fit? Read part 4 HERE.

Next: The rest of the kit: Will it fit? Read part 4 HERE.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.