Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

A versatile storage box: the Wolf Pack

A pair of Wolf Packs holds tools for a Defender 110 in Tanzania.I have yet to meet the perfect overlanding cargo box. Pelican cases are nearly perfect when contents absolutely, positively must be kept dry and dust-free, thus they are the box of choice for, say, photo and video equipment. But Pelican cases are quite heavy for their volume, and pretty expensive for everyday cargo. Zarges (or the similar Alu-Box) aluminum cases are strong, lightweight, and boast excellent interior to exterior volume, but are even more expensive (although you can consider the expense an investment as they last forever with reasonable care).

A pair of Wolf Packs holds tools for a Defender 110 in Tanzania.I have yet to meet the perfect overlanding cargo box. Pelican cases are nearly perfect when contents absolutely, positively must be kept dry and dust-free, thus they are the box of choice for, say, photo and video equipment. But Pelican cases are quite heavy for their volume, and pretty expensive for everyday cargo. Zarges (or the similar Alu-Box) aluminum cases are strong, lightweight, and boast excellent interior to exterior volume, but are even more expensive (although you can consider the expense an investment as they last forever with reasonable care).

But more economical alternatives always have some fatal flaw. The affordable Rubbermaid Action Packers are excellent for home storage, but their volumetric efficiency is abysmal and they leak if rained on, so you can’t leave them outside the vehicle when camped unless they’re under cover. If strapped down too tightly (i.e., properly . . .), they collapse. Lower-priced alternatives are even worse.

Several years ago in Tanzania I discovered the plastic ammunition cases used by the South African military, now commercially produced and known widely as Wolf Packs. They’re moderately sized and so easy to arrange in a cargo bay, completely rainproof and reasonably dustproof, and vertical-sided to avoid wasted space (except for hollow corner pieces). They stack securely for convenient storage at home. The Wolf Packs suffer from poorly designed latches—those familiar with them will call that a hilarious understatement— and the lids flex more than I’d like when called upon to do duty as a step, but otherwise they are sturdy, versatile, and sport a certain exotic flair given their origins. Front Runner Vehicle Outfitters is now a U.S. distributor, and for $40 each you can justify several—trust me, you’ll find uses for all you get. We have six, and just glancing around the shop I can see uses for another six. Or ten.

We found that a pair of Wolf Packs stacks and straps down perfectly in the shower grate of the JATAC, under the dinette table. Another rides near the door, and holds all the items we use for pitching camp: drain hose for the galley sink, leveling blocks, guylines and stakes for the awning, etc. I sourced some 1/4-inch thick aluminum diamondplate and fabricated steps for the lids of two of them, attached with small stainless bolts; the three now form a perfect staircase to access the camper when we’re parked.

I also keep two in the back of my FJ40. One holds recovery gear; the other contains a small stove and cook kit, water, and other odds and ends to make an emergency camp or an impromptu picnic.

A pair of Mac's Tie-Downs anchor plates and rings, bolted through each side of the dinette seat box, provides anchors for the ratchet strap that secures the boxes.

A pair of Mac's Tie-Downs anchor plates and rings, bolted through each side of the dinette seat box, provides anchors for the ratchet strap that secures the boxes. When not needed, the ring detaches instantly.

When not needed, the ring detaches instantly.

Front Runner's website is here. They also sell improved steel latches.

The analog iPhone

Ready for the bio-apocalypse: a steel-framed handgun and the amazing Pocket Ref

Ready for the bio-apocalypse: a steel-framed handgun and the amazing Pocket Ref

In the speculative-fiction novel Directive 51, author John Barnes postulates an alarmingly plausible near-future in which all plastics, synthetic rubbers, and oil-based fuels have been destroyed by maliciously created self-replicating nanobots and bioengineered microorganisms. All modern communication, transportation, and just about everything else is brought to a halt, and the world is plunged into chaos. The most advanced technology possible peaks at steam engines and vacuum tubes. The book is so believable that Roseann, normally a both-feet-on-the-ground skeptic, mentioned casually after reading it, “You know, it wouldn’t hurt to have a few cases of canned vegetables stored here . . .”

Given our remote home site, dependable well, and abundant wildlife (not to mention free-ranging cattle), we’d be in better shape to survive a bio-apocalypse than 99 percent of the U.S. population. And I feel about 99 percent better equipped to do so since my friend Bruce handed me a copy of Thomas Glover’s Pocket Ref.

I’ve used various one-subject pocket references before (wiring, plumbing), but this tiny 864-page book covers an array of subjects that is simply stunning. Look through the index and pick an uncommon letter—say, W. Now pick one entry out of the 31 listed under W—say, weather. Glover’s Pocket Ref will tell you the following things about weather: Beaufort wind scale; cloud types; cold water survival time; dew points; Fujita-Pearson tornado intensity scale; heat/humidity factors; hurricane intensity scale; ice thickness safety; weather map symbols, and wind chill factors. Over in the Fs, under formulas, you’ll find a staggering 105 entries, from Ohm’s law to antenna length to load on a wire rope or sling to sound intensity to voltage drop vs. wire length, diameter, and current.

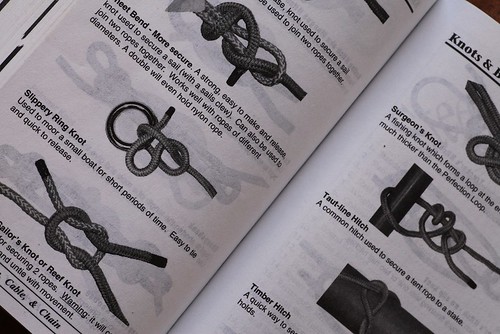

Knots will still work - but better stock up on sisal rope.Other entries: knots—lots of them—treatment for a sucking chest wound; steel tubing specifications; maximum floor joist spans; simple and compound interest factors; area formulas, solvent types; and I could go on for another 863 pages. Need to calculate how much water is left in a cylindrical tank of known diameter and length? No problem. Need to know the rank of the uniformed military personnel who show up after the apocalypse to declare martial law? No problem. Do you have a hard time remembering the geologic time scale (did the Miocene or the Pliocene come first?)—no problem. I can now quickly figure the BTUs available in a cord of Douglas fir, or the clamping force possible with a 15mm 8.8 bolt, or the proper hand signals for a crane and hoist operator. Amazing.

Knots will still work - but better stock up on sisal rope.Other entries: knots—lots of them—treatment for a sucking chest wound; steel tubing specifications; maximum floor joist spans; simple and compound interest factors; area formulas, solvent types; and I could go on for another 863 pages. Need to calculate how much water is left in a cylindrical tank of known diameter and length? No problem. Need to know the rank of the uniformed military personnel who show up after the apocalypse to declare martial law? No problem. Do you have a hard time remembering the geologic time scale (did the Miocene or the Pliocene come first?)—no problem. I can now quickly figure the BTUs available in a cord of Douglas fir, or the clamping force possible with a 15mm 8.8 bolt, or the proper hand signals for a crane and hoist operator. Amazing.

A reference book such as this shouldn’t be entertaining—its mission is to promulgate information. But it’s fascinating to simply browse through the Pocket Ref and see what you can learn. Take my advice: Buy one and just toss it in your glove box—if you come out one morning and find your tires have melted into blobs of bio-slime, you’ll be ready to face the future.

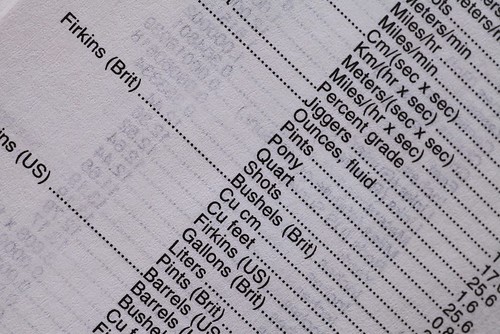

If someone in the New World wants to sell you a firkin of home-brew, you'll want to know just how much that is.

If someone in the New World wants to sell you a firkin of home-brew, you'll want to know just how much that is.

Available on Amazon—as long as Amazon still operates . . .

A proper camp breakfast

GSI Pinnacle griddle on the Snow Peak large Pack and Carry Fireplace with bridge attachment.

GSI Pinnacle griddle on the Snow Peak large Pack and Carry Fireplace with bridge attachment.

Hickory-smoked bacon sizzles on a griddle. The fat pools, spreads, and infuses eggs scambling in butter nearby.

Did your salivary glands just twitch? Of course they did. Any vegans reading this—you had the same reaction. Oh, you might suppress it, pretend it didn’t happen, but somewhere deep down your atavistic omnivore is beseeching you to reject dietary self-flagellation and embrace your rightful place in the food chain.

We all know that eating bacon and eggs on a daily basis is probably not a wise habit—and besides, it wouldn’t be a treat then. But there’s no harm in indulging on a camping trip. Imagine: Dawn breaks over distant peaks, a breeze stirs pine trees overhead, blue jays greet the new day with a raucous chorus, and you stand over a fire with a cup of coffee, inhaling the scent of . . . frying tofu? C’mon.

To do bacon and eggs—and many other proper camping dishes—correctly it’s nice to have a griddle. At home we use cast iron, but that’s a bit heavy for a mobile kitchen when you consider its specialized niche. So we recently tried the Pinnacle Griddle from GSI Outdoors. It’s aluminum and just a bit over two pounds, yet offers a generous 10 by 18-inch cooking area surrounded by a grease moat. The surface is some non-stick space-age stuff—which we eschew at home but which is nice for cleaning up with a limited water supply. The back is hard-anodized (GSI offers a non-anodized version called the Bugaboo).

That one-and-a-quarter square foot size is perfect because, a) when we do eat bacon and eggs we eat a lot, and, b) because it fits nicely over our large Snow Peak Pack and Carry fireplace. (Snow Peak makes a cast iron griddle insert for their fireplace bridge, but it's ridged, and suitable only for cooking meat; we also use our griddle for pancakes and flatbreads.)

The grease moat keeps excess grease off the main cooking area. On the Snow Peak fireplace bridge, you can carefully slide the griddle to the side and pour off excess into a container.

The grease moat keeps excess grease off the main cooking area. On the Snow Peak fireplace bridge, you can carefully slide the griddle to the side and pour off excess into a container.

Cooking over mesquite coals accomplishes two things. First, it adds to the atmosphere of the experience; second, it keeps that atmosphere out of the camper, where too much bacon grease and smoke too often would not be good for the canopy and upholstery. The griddle also fits in the fireplace’s (insanely obtuse) carrying case.

The Pinnacle Griddle’s aluminum is fairly thin, which means low heat will suffice, but not so thin that there were hotspots—it heated and cooked evenly for both bacon and pancakes. However, the surface of ours also came slightly convexly warped, so that an egg cracked in the middle would sort of elongate toward the edge until corraled with a spatula. I plan to see if it will flatten, using some heavy boards and judicious pressure.

Cooking eggs and tortillas in the bacon grease. Can life get any better?

Cooking eggs and tortillas in the bacon grease. Can life get any better?

In the meantime, it’s working just fine—and we’ve successfully subverted several vegans at group camps.

Visit GSI here.

The Audience Phenomenon

I was chatting with someone after one of my tool kit demonstrations at the 2013 Overland Expo, and he asked if I ever experienced the “audience phenomenon.” After he explained I laughed and said I certainly did—but not the same way most home mechanics do.

If you work on your own vehicles, you’re probably familiar with the cosmic rule that makes visitors show up out of nowhere to watch and comment or, more often, chat about subjects completely unrelated to the task, usually at just the moment when your frustration with some obstinate part or inaccessible fitting has reached a crescendo. Concentration goes out the window and progress grinds to a halt. Even if it’s someone whose company you normally enjoy, it’s a maddening interruption—and if it’s that neighbor across the street who uses binoculars to determine when he can show up and continue his theories about how the U.N. is secretly taking over the curriculum of our public schools, you’d be forgiven for musing on alternate uses for your 18-inch breaker bar.

However, Roseann and I live 40 miles from Tucson, in a spot so difficult to find that Google Maps will give you the wrong directions. Needless to say I’m not often interrupted by casual visitors.

At least, not human visitors.

We’re surrounded by fine Sonoran Desert habitat, keep several troughs filled with water around the yard, and regularly toss out generous handfulls of black oil sunflower seed. In response, the local wildlife has decided that our presence is to be considered no more troublesome than that of the lower servants in Downton Abbey. Even the resident zebra-tailed-lizards—normally skittish—don’t move out of our way, and if we happen to sleep past murky pre-dawn, we’ll awake with deer looking impatiently through the windows wanting a drink, cardinals and quail on the porch pecking forlornly at the clear plastic bin that holds the sunflower seed, and a Harris’s ground squirrel that’s learned to climb one of the porch chairs to check for movement in the cottage.

A few years ago I started collecting snapshots taken while I worked on various vehicles. The Clark's spiny lizard in the lead photo was a resident for four years. She got so used to being fed crickets that any time we came out of the house she'd run full-tilt at us, a trick that once got her underfoot of Roseann and cost her the end of a tail. It got so that if I sat on the floor to work on something she'd climb up my leg and I'd have to toss her off in order to get anything accomplished:

We live at 3,800 feet elevation, which is habitat for both the diminutive Coue's whitetailed deer and the larger mule deer. Ninety percent of our deer visitors are the whitetail, and multiple generations of does have taught their fawns to ignore the human fiddling about with the big shiny contraption and enjoy the water:

(Parenthetical remark: Only while compiling these photos did I notice how many were taken while I was fiddling with the British/Indian motorcycle. Just sayin' . . .)

Bucks - especially mule deer bucks - tend to be much more wary than does, at least at our place. However, one day while working on my bicycle I looked up to see a beautiful mule deer drinking from the bird bath:

Another day while I was tracking down an electrical fault on the, uh, yeah . . . British/Indian motorcycle, I looked up to see a juvenile tortoise heading across the porch toward me. With scant regard, it continued an unerringly straight path through my tools, past me, and out the other side:

It's good that I like to start early on vehicle projects, because sleeping in is not an option around here if you're the slightest bit sensitive to that feeling of being watched:

On the other hand, once you're up you need to watch where you step while doing your servant duties. Notice anything unusual in this photo?:

If you missed it, look closely in the bottom left corner:

I moved this one off a few hundred yards, but rattlesnakes are welcome residents, since they eat rodents that might otherwise wreak havoc on wiring and hoses in our vehicles. For two years I was stumped by how mice were gaining access to the trunk area of our old Porsche and setting up housekeeping:

I seriously considered dropping a diamondback into the trunk and leaving it for a week or so, but the thought of how exciting driving the car would be if I couldn't find it again dissuaded me. I finally found the mouse access point under the steering rack, and sealed it with expanding foam (don't tell the Porsche purists).

I usually try to finish up work before dark, since burning bright work lights wastes the electricity we produce through solar and wind energy, but occasionally a project will run late. Visitation drops off markedly then - at least it seems to. Some time ago our driveway security camera caught this image just a few yards from the carport:

Hey - as long as they keep quiet, the mountain lions are welcome to hang around and watch.

Four-by-four Driving, third edition

Poor Tom Sheppard. Every time he’s sure he’s revised his seminal Vehicle Dependent Expedition Guide and the more tightly focused Four-by-four Driving for the last time, existing stocks run out and a waiting list of pleading would-be buyers grows too long to ignore (and, in the case of VDEG, profit mongers exploit its scarcity and eBay prices go through the roof). Just a year and a half ago I reviewed the second edition of Four-by-four Driving (HERE), and I’ve just received the third edition.

Virtually all my comments regarding edition two hold for edition three. If you’re new to four wheel drive and just want to know how to engage the front wheels, this is not the book for you. If, on the other hand, you want to know why engaging the front wheels does what it does, you’ll find the answers here—and you’ll become a better driver for knowing them.

Tom could have simply printed more copies of the second edition, but that would satisfy no one with his level of solo-explorer and ex-test-pilot attention to detail, so relevant sections have been revised to address new technologies in four-wheel-drive vehicles.

Simply put, if you’re reading this post, and you don’t have it, you should. It’s available directly from the author (with very reasonable cross-Atlantic postal charges) here: Desert Winds Publishing.

P.S. A new edition of Vehicle Dependent Expedition Guide will be available this summer, also direct from Desert Winds. Put your name on the list now.

The ins and outs of airing down

Airing down in Egypt

My early four-wheel-drive experience was strictly trial and error, heavy on the error. A friend owned a beat-up mid-60s FJ40 shod with skinny Armstrong True Tracs and equipped with a Ramsey winch wrapped with a rusty steel cable. We took that thing everywhere, including trails around southern Arizona that I’d later learn were rated 4+ and even 5 on the vehicle-based system. When we got stuck or couldn’t drive up some ledge, which was frequently, we’d simply unspool the winch cable, wrap it around a big rock and hook it to itself (I know, I know), and pull ourselves out. The rocker panels on that poor 40 eventually got battered into gentle arcs (call it a “redneck body lift”). But we had fun and learned a lot—enough that when I got my own, much nicer, FJ40 I was able to keep its rocker panels the way the ARACO body plant meant them to be.

This do-it-yourself approach explains why I came late to the concept of airing down tires on off-pavement trails and four-wheel-drive routes—I simply didn’t hear about it until well into the 1990s, when I began subscribing to magazines that included articles by expedition travelers such as Tom Sheppard. It never would have occurred to me on my own that deliberately letting air out of one’s tires could be a good thing.

Now, of course, the benefits are well-known to anyone who has read anything about overland travel: Reducing tire pressure to suit the conditions allows the tire to more effectively mold itself to the terrain. That increases traction, which reduces wheel spin. That in turn reduces trail damage as well as stress on the vehicle’s drivetrain and wear on the tire itself. In soft sand the enlarged footprint (which comes mostly from lengthening of the tire carcass, rather than widening) provides hugely increased flotation. It’s basically a win-win-win technique, as long as one is circumspect about mixed terrain: You might choose 14 psi for soft sand unless that sand is interspersed with sharp rocks likely to puncture a sidewall (as we encountered in Egypt with the dreaded kharafish—razor-edged lumps of limestone). Airing down even enhances ride comfort on rough roads, as it allows the tire to conform to small obstacles rather than bouncing over them.

If the benefits of airing down are so well-known, why don’t more people practice it? It boils down to two issues: sheer laziness, and lack of proper equipment. And the former is often caused by the latter. If you have to deflate each tire one at a time using the awl on your Swiss Army knife or the button on the back of a tire gauge, and if re-inflation is a 45-minute process tackled with a $29.95 compressor (“with flashlight!”) better suited to blowing up volleyballs, you’re just not likely to do it unless you actually get stuck first.

Since tire failure—whether a simple puncture, losing a bead, or damaging a sidewall—is still the number one cause of vehicle breakdowns, a high-quality compressor should be part of your kit anyway. In fact, after the most basic upgrades on any 4WD vehicle—tires, for example—a proper compressor comes near the top on my list. Maybe even before a fridge.

With a good compressor to handle re-inflation, your next goal is to avoid prolonged genuflecting in front of each tire, letting air hiss out slowly though the valve. There is a dirt-cheap way to accomplish this: Buy a valve-core removal tool. Although it seems drastic, removing the valve core is the absolute quickest way to deflate a tire, yet it’s not so quick as to be difficult to control. Your pressure gauge will still work, and you just need to be ready to reinsert the valve core when the pressure gets close to your target.

The big problem with this technique—besides the fact that it’s a manual, one-at-a-time procedure—is that the tire pressure will do its best to wrest the tiny valve core out of your grasp just as you’re removing (or reinserting) it, and send it flying ten feet over your shoulder. By the time you find it (assuming you can), you’ve got a flat tire.

A safer and more stylish approach to the VCR technique can be had with the ARB E-Z Deflator. This tool comprises an elegantly complex brass fitting with a hose and gauge. The fitting screws on to the valve stem, and a separate knob then unscrews the valve core but contains it securely within the mechanism. Pulling back on the collar attached to the air hose and gauge then allows air to escape with a satisfying whoosh. Push back in to stop the flow and check the pressure. It appears to be just as fast as the riskier method—I deflated a 235/85 R16 BFG All-Terrain (my reference tire for the entire test) from 40 psi to 18 in 33 seconds flat.

However fast it is, the ARB still requires full operator attention—which brings us to automatic deflators. While not as quick individually as valve-core removal, you can be doing other things, such as chatting to your friends, getting a snack, or checking the vehicle, while the tool does its work, and if you have multiple deflators the total process can be quicker than the fastest one-at-a-time technique. In fact, with two of the types of deflator reviewed here, you can drive off while they’re attached and working, thus reducing the time stopped to a couple minutes, and pretty much eliminating your last excuse not to do so.

Left to right: Staun II, Trailhead, and CB Developments automatic deflators

The mechanics of an automatic tire deflator are deceptively simple. Essentially the device comprises a plunger with a seal, and a spring calibrated to compress at a certain psi to allow air to flow past the seal and out of the tire. By using a screw-in cap as a base for the spring, its tension can be altered to allow multiple settings in one deflator. The engineering feat is to produce a device that will do this accurately and repeatably over a broad range of pressure.

Coyote Enterprises Staun II $80 (set of four)

Staun is the grandfather of deflators, designed in Australia in 1998. I had one of the early sets, and while they were convenient, I found the target pressure to vary by as much as two or three psi—potentially critical if you’re airing down to the low teens (below one bar) in soft sand. Go too low unintentionally and apply too much welly or steering lock and you can pop the tire bead off the rim. So I was curious to see if the newer style would be more accurate.

The second-generation Staun (made in the U.S., and covered by a lifetime warranty) benefits from a number of modifications. The claimed range is now an astonishing 3 to 50 psi—the original Stauns needed three part numbers to cover this span. Two sets of springs are included to adjust the limits. Also, there is a manual start ring, which among other things allows you to initiate deflation if there is insufficient pressure difference to trigger it otherwise—say, if your tires are at 21 psi and the Stauns are set to 18, or if you want to bump the pressure back down after airing down on a cold morning and driving until the tires warm up (they regain a bit of pressure when hot). The new Stauns also take only two or three turns to lock onto the valve stem. Finally, the maker now sanctions driving off with the Stauns in place and letting them work en route.

Made of solid and confidence-inspiring brass, the Stauns come with a clear set of calibrating instructions. First, manually deflate a tire to the nominal pressure at which you want to set the Stauns. Turn the hex locking nut and the top of the deflator all the way down (clockwise). Now screw the deflator on the tire until it’s snug, and slowly turn the top of the deflator counterclockwise until air is released. Immediately turn it back clockwise until the air just stops, then turn the lock nut up until it locks the body in place. That’s it. If you prefer different pressures on the front and rear of the vehicle, you can set two to each, and file a notch in the edge of one pair to identify them.

I used 18 psi as my target—it’s a good rough-trail pressure for my FJ40 and many similar-sized vehicles. If you’re quick you can calibrate all four deflators on the reference tire without adding air, but I bumped it back up with the compressor after two (the 235/85s don’t have a lot of volume). With the tire reinflated to 40 psi, I screwed on one of the Stauns and clicked a stopwatch. Three minutes and 19 seconds later, the device snapped closed, and my calibrated gauge confirmed that the shutoff pressure was dead on 18 psi. Reinflating to various pressures and trying the remaining three produced nearly identical results: None was more than a half pound off. Furthermore, with the manual-start ring I found I could initiate deflation even when the tire pressure was only two or three psi higher than the set pressure.

You can estimate a new setting on the Stauns in the field by loosening the lock ring and turning the cap. One turn either direction (clockwise to increase, counterclockwise to decrease) equals “three to four” psi according to the instructions. Mine seemed to do about three per turn, but it’s definitely a rough guide.

Given its accuracy and additional features, the Staun II is clearly a worthy upgrade to the original.

Trailhead $75 (set of four)

Trailhead (originally Oasis) deflators pioneered the “drive-away” function, which made stopping to air down a two-minute procedure. While the Stauns now offer the same capability, I have to admit I was hesitant to do so given their relatively weighty brass construction. Not so with the Trailheads—each slim anodized-aluminum unit weighs barely ten grams, compare to 25 for a Staun.

The procedure for calibrating the Trailhead deflator is a contrast as well. Using the included 5/32 hex key, you unscrew the internal cap until it is perfectly flush with the body. This represents the lower end of the range (5 psi on my 5 to 20 psi model; a 15 to 40 model is also available). From there, each full turn back in supposedly represents an increase of 1.5 psi. To get to my target of 18, I counted up—6.5, 8, 9.5, etc.—until I got to 17, and then added about two-thirds of a turn to estimate 18. I screwed on the deflator and hit the stopwatch, and it shut off just two minutes and 19 seconds later. However, when I checked the pressure in the tire it was at 20 psi. I gave the cap a full turn back out and tried again. This time, after two minutes and 31 seconds, it was within a half pound of 18. I tried the same procedure with the other three units, and each one stopped around two pounds short of the target pressure. So setting the Trailheads precisely required more fiddling. Once finished, however, they remained accurate.

The Trailhead deflators have no manual start function, and the instructions caution that initial tire pressure must be roughly twice the set pressure for them to self-initiate. I found that a bit pessimistic—mine would all initiate at 32 psi when set to 18. But trying again at 30 produced only silence. So if you drive a vehicle that takes that 30 psi on the road, you’ll have to air down to 16 or below for the Trailhead deflators to work.

The Trailheads can be bought in mixed colors —aluminum, red, or blue—making it easy to identify when you set them up differently for front and rear tires. They are made in the U.S. and come in a pouch with instructions, the hex key, a tire gauge, and a handy tire deflation guide.

CB Developments Mil-Spec Tyre Deflation Valve $100 (each)

Compared to the lengthy calibration sequence necessary to set up the Staun and Trailhead products, the procedure for CB deflators couldn’t be more different: There isn’t one. Push and turn the knurled knob so the pin indexes with the target psi on the body of the deflator, and screw the assembly on your valve stem. That’s it. No need to deflate a reference tire, and no need to use math and a wrench if you want to change settings for differing conditions (or different vehicles) in the field—just turn the knob to the new target. I set one of the CB deflators to 18 psi, screwed it on my 40-psi test tire, and just two minutes and 22 seconds later it was finished, beating out both the Staun and, by a slim margin, the Trailhead. Furthermore, every setting I tried, all the way down to 10 psi, was within a half pound of my calibrated gauge. And the deflator would initiate with as little as two pounds of difference between the tire’s pressure and the target. An excellent performance.

Of course, you pay for that convenience, speed, and accuracy. A single CB deflator costs significantly more than an entire set from Trailhead or Staun. A full set of four would be a frightening chunk of cash. And you cannot drive with the bulky CBs in place, so are tied to the time it takes for however many you own to do their work. The CB deflators also lack the upper range of the Stauns or Trailheads—the highest range model carried by Extreme Outback Products, the U.S. distributor, stops at 20 psi (CB Developments makes another that extends to 24). That means those of you with Sportsmobiles and other heavy rigs, who consider 40 psi to be “aired down,” are out of luck. In fact 20 psi might be marginal for our Tacoma and Four Wheel Camper in anything but soft sand; on the road we keep 50 psi in the rear E-rated BFGs.

Conclusions

All these deflators worked as advertised, and all were very accurate once calibrated. So in a way you can’t go wrong. But in the end I did have preferences.

The Trailhead deflators boast the lowest cost—I’ve seen street prices under $60 for a set—and they were significantly faster than the Stauns. The multi-color option is a nice feature. Their single-hex-key adjustment makes them easier to manipulate than the two-piece adjusters on the Stauns—although as we have seen, the Trailheads take more fiddling to arrive at the target setting. But their biggest drawback is the lack of a manual-start function, and the significant difference in pressure necessary for them to self-initiate. I can recall many situations I’ve been in where they simply would not have worked.

The Staun II deflators run roughly $10 more per set than the Trailheads. However, for that you get a much wider pressure range in one part number, faster calibration, and the ability to initiate deflation with just a few psi difference between the tire and your target. Their sole downside was the slower speed, if the difference between two and a half minutes and three and a quarter minutes is critical to you. I’ll be curious to see how a potential “Trailhead II” deflator responds to the Staun II challenge.

The CB deflators are in a league of their own, in performance, convenience, and price. As long as the psi settings you require lie within the range of the device, there is no easier or more accurate deflator. I keep a pair in my FJ40, and their versatility more than makes up for the fact that I have to deflate tires a pair at a time. If I need to reduce pressure from my nominal 18 to, say, 14, it’s the work of an instant to change the setting—no guesswork needed.

Among the automatic deflators, then, the CB Development Mil-spec product wins if price is no object and the range fits your vehicle. If you baulk at the thought of a $400 set of deflators (or even $200 for a pair), an $80 set of Stauns will serve admirably—and suit a wider range of vehicles to boot.

As to the ARB EZ Deflator, while it is a manual tool, it is in many ways the most versatile of the bunch. If you have a Global Expedition Vehicle* at one end of your garage that you only air down to 55 psi, and a rock buggy with beadlocks at the other end that you take down to four, the ARB is the only tool here that will handle both—and anything in between. At $40 it is the least expensive of all these options. (*That is, ahem, if you didn’t order the GXV’s optional central tire inflation system, which makes this entire article a moot point for you . . .)

Searching for a bottom line, I ran a series of back-to-back double-blind experiments controlled for temperature, humidity, and elevation, and determined that the mean time to stop the truck, deploy a set of Staun deflators, let them finish, and pack them away again is six minutes 37 seconds—which happens to be the exact time it takes to retrieve a cold Coke from the fridge of the JATAC and finish it while sitting in the shade.

Staun deflators at work in the Rift ValleySource links: ARB, Trailhead, Staun (Coyote Enterprises), CB Developments (Extreme Outback Products)

A compressor for the Boss air bags

The bottom switch adds air to both bags simultaneously. The two buttons above bleed air individually to level side to side.

The bottom switch adds air to both bags simultaneously. The two buttons above bleed air individually to level side to side.

The Boss air bags I installed to level the JATAC (see HERE) have been working perfectly so far. We recently drove into Mexico’s Sierra Madre to retrieve some trail cameras we had set up to survey mammal populations on a remote property owned by the Catholic Church. The last 12 miles requires four wheel drive, and several sections flexed the suspension past its limit so we wound up with one wheel in the air. The Boss bags took it in stride.

When I installed the bags I temporarily hooked up a simple manual-fill arrangement. But the kit came with a very fine compressor and a remote switch and gauge, so last week I installed the complete system to give us push-button control of the bags.

We decided to install the switches and gauge in the camper rather than the cab of the truck, since it’s easier to check the level back there. It also gives us the capability to quickly tweak both the fore and aft and side to side level of the camper when parked. The question was, where to mount the gauge/switches, as well as the fairly bulky compressor. I located what seemed to be a perfect spot for the controls just inside the camper’s door on the left, above the two switches that control the LED interior footlights and the exterior floodlamps. Since the battery compartment is right behind this spot, that would simplify wiring.

Pilot holes prior to cutting the opening. Painter's tape prevents scratching.

Pilot holes prior to cutting the opening. Painter's tape prevents scratching.

The compressor was more problematic, but eventually I located a spot I thought would work, inside the access port for the left rear turnbuckle that secures the camper to the truck. At the back, inside the hatch, the compressor barely fit vertically against the outside wall of the battery compartment—again minimizing the wiring run.

The Boss controls come mounted in a steel panel designed to be attached to the underside of a dash, and that wouldn’t work for this application. I had some 1/4-inch-thick high-density plastic sheet lying around, so I cut a panel from that, drilled it for the gauge and switches, and painted it black with Krylon formulated for plastic. Then I trepidatiously took a jigsaw to the camper’s cabinet and opened a spot for the assembly. The result looked decent and is effortless to access for adjustment.

The compressor took much more winkling, especially because I wanted it secured properly so we’d never have to worry about it vibrating loose. With the help of a sidewinder drill and a bit of blood loss I was able to mount it to the plywood battery compartment wall with stainless bolts and fender washers. I ran the air lines down through a hole I drilled in the bed inside one of the stock little storage compartments. (Doing so confirmed that the fiber-reinforced material Toyota uses on their composite beds is tough stuff indeed; it felt and smelled like drilling through thick fiberglass.)

With everything hooked up, adjusting the level on the truck is as simple as pushing a switch. The way the system is designed, both bags fill at once, and you then use individual buttons to deflate one or the other bags to even them side to side. The clever gauge has two needles, one red and one green. You hook them up so nautical running-light rules apply: red for port (left) and green for starboard.

I won't say having to climb under the truck with a compressor to fill the Boss bags manually was exactly . . . hell . . . but the complete system sure makes it easy.

A Hi-Lift jack mount for the JATAC

The Hi-Lift jack is a useful tool, but it’s also a pain to carry securely on a vehicle, especially if you want to keep it reasonably accessible. I’ve seen many mounts that achieved one but not the other—and too often, safety loses out to convenience. Sadly I had neither a camera nor a cell phone with me a few years ago when I spotted a Hi-Lift mounted horizontally on top of a bull bar on a truck, just above hood level—and secured with a pair of tightly wrapped bungee cords. The imagery of what could happen if that truck were smartly rear-ended was . . . colorful, not to mention what could happen to an innocent person if Mr. Thatoughttaholdit rear-ended someone else. For reference, a 30-pound Hi-Lift mounted on a vehicle that comes to an abrupt halt from 30 mph exerts a force of 903 foot-pounds of energy on whatever is holding it to that vehicle.

I see a lot of Hi-Lifts bolted to roof racks—secure, safe but for the modest impact on CG, and more likely to stay free of road grime, which can quickly foul the Hi-Lift’s mechanism. It’s not a bad spot if you can access it without climbing. Also good are dedicated mounts on rear tire carriers (as opposed to the ones that bolt behind the spare tire, which are a pain). I suppose a properly engineered mount atop a bull bar is okay; it’s certainly handy there. But I’ve never seen one that didn’t impede forward vision and access to the engine compartment. And on a strictly personal note, it looks just a little too, well, Moaby, if I may coin a word.

Mounting a Hi-Lift on the JATAC presented its own challenges. The roof is out of reach and devoted to solar panels. We’ll be installing a Hi-Lift-compatible winch bumper up front soon, but that was rejected for the reasons stated above. And we’ve also decided not to install a rear bumper with big swingaways, to hold down mass at the back of the vehicle. What did that leave us?

I asked Tom Hanagan at Four Wheel Campers about fabricating a mount that would bolt to the rear wall of the camper, directly through the vertical aluminum frame members, to hold the jack vertically to the right of the door. He thought it could work, but was hesitant to sanction the idea unequivocally. And that location would still hang the mass off the back of the vehicle.

Then, while walking around the truck stroking my chin and pondering, I noticed the area where the camper overhangs the truck’s bed on each side. I held up a Hi-Lift to the spot, and it tucked in as though designed to ride there. The location would be completely out of the way yet quickly accessed, and while the weight would still be toward the back, it was significantly forward of a rear wall mount. I decided to mount it on the passenger side, to compensate for the weight of the truck’s fuel tank and the camper’s water heater, both of which are on the driver’s side.

I used two short lengths of two-inch-square steel tube for the brackets. First I located the spots I’d drill through to hang the brackets—one in the propane tank compartment, one behind the fridge inside the camper. I used two 1/4-inch grade 8 bolts with fender washers to anchor each bracket through the plywood (which fortuitously is double thickness in the propane compartment, where the heaviest part of the jack would be). To secure the jack to the brackets, I used a 3/8ths-inch grade 8 bolt on each one. The bolt was too long to slide into the tube and down through the hole I drilled, so I drilled an adjacent hole and made a slot to get the bolt through. I tack-welded each bolt in place, and welded a short piece of thicker steel under each bolt as reinforcement. On the rear mount I extended the reinforcing strip forward and drilled a hole through it, to secure a padlock through the mount and the standard of the jack.

Positioning the mounts laterally was tricky. I wanted the jack tucked all the way under the camper, but needed clearance to drop it free of the mounting bolts without scraping the sheet metal of the truck’s bed. With a bit of winkling, I got them just about right. One needs to be cautious and not just yank the jack free; it must be twisted slightly to get in or out without hitting the lifting mechanism on the back of the bed, but it’s easy to do single-handed. To secure the jack to the bracket I use a grade 8 nut to hold the weight, and a nylock wingnut to keep it snug.

The next issue was to ensure the jack’s operating handle stayed secure while driving. I have a stock rubber handle keeper, which slides over the handle and the standard, but it can migrate when subjected to vibration. So I fabricated a modified version from some half-inch-thick polyethylene I had around, and cut two polyethylene pieces that lock the keeper in place via a spring clevis pin. Done.

The next issue was to ensure the jack’s operating handle stayed secure while driving. I have a stock rubber handle keeper, which slides over the handle and the standard, but it can migrate when subjected to vibration. So I fabricated a modified version from some half-inch-thick polyethylene I had around, and cut two polyethylene pieces that lock the keeper in place via a spring clevis pin. Done.

With the jack’s base plate in place, the right turn signal is just slightly obscured from above and behind the truck. It would only be an issue if someone in a semi was close behind us, but we’ll keep the base plate in our recovery kit anyway, and thus avoid potential legal issues as well. With that gone, one needs to be absolutely certain that the selecting lever of the jack is in the “lift” position, otherwise the entire lifting mechanism could migrate off the back of the standard while driving (or be propelled off it in an accident). Not good. I’ll use some sort of secondary arrangement as backup, likely a short bolt and wing nut. (Note here: A Hi-Lift should always be stored with the lever in the lift position anyway.)

So far the arrangement works perfectly. The jack is totally out of the way, yet easy to retrieve. In terms of safety, the mount should be secure through any but the most catastrophic impact: The force applied by the brackets to the floor of the camper would be in sheer; with four grade 8 bolts securing the assembly I’m sanguine.

Next task: to mount a front bumper on the JATAC that will properly accept a Hi-Lift jack for recovery purposes.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.