Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Friction . . .

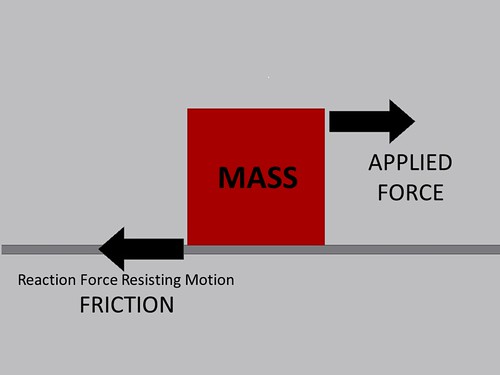

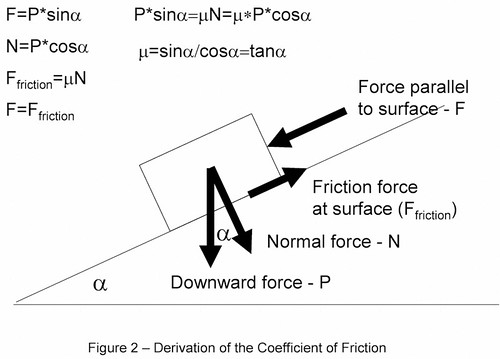

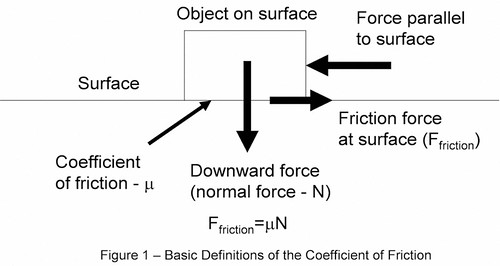

Have you ever tried to slide a cardboard box full of books or other weighty contents across a floor? Did you notice that the box was difficult to get moving, but that once sliding it became easier to push?

If so, you’ve experienced the difference between static and kinetic friction.

While it might seem counterintuitive, friction between two surfaces is greater when there is no movement between them. Once that initial bond is broken with an applied force, friction is reduced. That force can be a push or pull, as when you moved the box of books, or another force such as gravity. Put that same box of books on one end of a table and lift that end. The box will stay put until gravity overcomes the static friction, at which point it will slide right off the other end.

What does this have to do with us? The differences between static and kinetic friction explain many of the interactions between a vehicle’s tires and the road. Again counterintuitively, when your tires are rolling along in a straight line there is essentially no movement between the contact patch and the road aside from slight hysteresis in the tread. When you apply force to the tire, during acceleration, braking, or cornering, you’re still dealing mostly with static friction—right up to the point when the tire loses traction and begins slipping, when kinetic friction takes over. That’s why locking up the tires during a panic stop increases braking distance, why an early Porsche 911 whose rookie owner lifts off the gas pedal in a decreasing-radius turn is likely to wind up backwards in the bushes, and why a four-wheel-drive vehicle or motorcycle climbing a steep slope suddenly stops climbing when the wheels start spinning.

Rubber generates friction essentially three ways: though adhesion, deformation, and wear. Adhesion refers to the simple stickiness of the material. Adhesion friction is thought to be created by transient molecular bonding between the adjacent materials. Deformation occurs when the rubber in the tire molds to minute imperfections in the surface and creates a momentary mechanical bond (also called keying). Tearing is just that: if the tire’s tread material is stressed beyond its tensile strength, it sheds microscopic particles of material, and that process absorbs energy, which increases friction.

These principles apply to a tire turning on a loose surface as well, but in varying degrees. Frequently when a tire loses traction, it has not lost traction against the substrate directly under it; rather that layer of substrate directly against the tire is shearing against the material beneath it. You get an exaggerated example of this when a tire fills with mud and spins. A whole bunch of mud is sticking to the tire quite happily, but it’s slipping against the mud below.

Awareness of that frequently thin line between static and kinetic friction can help make you a better driver or rider. The trick is to balance the throttle (when climbing) or brakes (when stopping or descending) to keep the tires just this side of that edge. Of course, most modern four-wheel-drive vehicles incorporate computer-controlled devices that do some or all of it for you. I recently experienced Jeep’s Hill Descent Control (HDC) on a steep, bouldery downhill trail. Even though I was aware of the capabilities of the sytem, it was unnerving in an automatic-transmission vehicle to simply select low, push a button on the dash, and then head over the edge, foot off the brake pedal. I could hear the ABS engage the brakes on individual wheels to keep the speed down to a comfortable crawl. In my FJ40, even though it has a manual transmission and a very low first gear in low range, engine braking would not have been sufficient to control the speed on a descent this steep, and I would have been actively cadence-braking—intermittently pumping the brake pedal until the wheels almost locked—to approximate what the Jeep did on its own (except, of course, I could not have engaged the brakes individually). It was an impressive performance, if completely reliant on software.

Anti-lock braking systems are becoming prevalent on motorcyles as well—in fact the EU has mandated ABS on all bikes larger than 125cc beginning in 2016.

Likewise, modern traction-control systems such as Land Rover’s Terrain Response can detect when the static/kinetic line has been crossed, using speed sensors at each wheel, and will reduce torque to or brake a wheel that has lost traction on a climb or cross-axle ditch, sending power to the opposite wheel. I had equivalent terrain-conquering capability in the long-term 2008 (pre HDC) Jeep Wrangler Rubicon I drove for two years, but the software part of the equation was in my head, as I chose when to disengage the Jeep’s front sway bar to increase suspension compliance, and when to engage the front and rear differential lockers to prevent wheelspin. The single real-world advantage there was the fact that, unlike Terrain Response, I could tell when a difficult section was coming up several feet before I actually reached it, and take the appropriate actions proactively. Terrain Response (and its cousins) can only respond when its sensors detect that a wheel has lost traction, a second or two after the static/kinetic line has been crossed. Nevertheless, these automatic systems make child’s play of situations that used to require considerable finesse and experience.

Is that a good thing or a bad thing? You decide—but, just as when navigating with GPS versus map and compass, it’s a wise thing to have backup skills. If someone with a new Range Rover were to ask me the best way to become proficient at off-pavement driving, I’d say, “Buy a Series III 88 and start with that.” If you can master a manual-transmission, straight-axle, leaf-sprung, open-diff Land Rover—and the concept of static versus kinetic friction—you’ll be able to climb back in the Range Rover and soon have that computerized wizardry doing your bidding, instead of just being along for the ride.

Tire review: Big Block Adventure

by Bret Tkacs, for Adventure Motorcycle Magazine

In early 2012, Kenda released the Big Block Adventure tire to compete in the emerging big-bike knobby market. ADVMoto put a set of Big Blocks to the test on the back trails of Baja, Mexico, and then continued north up the west coast to Washington state. Back then, the Big Blocks were good performers, and on par with the competition, but lacked mileage and shed their skins faster than other big-bike knobbies we’re accustomed to, such as the TKC80 and Metzler Karroo. Kenda took note of this and their engineers worked over the Big Block with a revised tread pattern and new compound.

The casual eye won’t see the difference, as the tread pattern looks very similar. The only way we could tell they were the new tires was by measuring the space between the tread blocks. The newer tires have a block pattern slightly tighter, which puts more rubber to the road/trail.

We recently mounted up our fresh set of tires and headed off to Moab to put them to the test. After riding 800 miles of jeep trails and gravel roads, as well as over 2,000 miles of pavement on our loaded test bike, the Big Blocks were still holding out.

The bottom line is that Kenda has a winner with good off-road performance, good street manners, and mileage that equals the competition. Highly recommended.

Pros:

- Still a top performer off-road

- Performs well for a knobby on the street

- Improved mileage over earlier version

- Price point winner

Cons:

- Less prestige than big name brands (ego)

- Like all big bike knobbies it has a short life span (equal to other knobbies, though)

Bret Tkacs works for PSSOR Training

The blue vinyl table is dead!

A few years ago on a long road trip, Roseann and I opted for convenience over our usual preference for solitude, and stopped for the night in a developed campground: picnic tables, barbecues, flat sites, perfectly symmetrical pine trees—actually quite nice as such places go. That evening an enormous motorhome inched carefully into a nearby slot. The driver emerged just long enough to open a side panel and pull out a remarkably colon-like corrugated hose, which he plugged into his deluxe site’s sewage receptacle. Another umbilical fed electricity to the behemoth. The man then scurried back inside, and soon I heard the sound of some TV program on what I assumed had to be at least a 40-inch flatscreen. And that was the last we saw of either him or his wife.

I try not to judge fellow travelers on the size or splendor of their vehicles. After all, to someone in a CJ5 with a Eureka A-frame tent our Four Wheel Camper must seem pretty posh. But, while the camper provides us a cozy, stormproof home away from home, holing up inside is not the goal when we’re traveling—even in Jellystone Park. In good weather we like to be outside as much as possible. With the camper’s excellent Fiamma awning deployed, and a table and chairs set up, we can lay out snacks and drinks, then tackle some weighty biological issue like seeing how many bird species we can document while sitting down. “Nine species in one martini!” Roseann is likely to announce (although identification skills wane somewhat after the second, and we're likely to record birds never seen in this hemisphere . . .).

Where was I? Right: Until recently we relied for our outdoor table on one of those ubiquitous roll-up blue-vinyl-covered things with the screw-in aluminum legs. It was ugly and wobbly, but perversely durable despite my best attempts to “accidentally” destroy it. A Maasai shuka used as a tablecloth improved its looks immeasurably, but I still knew what was underneath . . .

Then, a few months ago, Roseann emailed me (from across the room) a link to the Front Runner camp table, designed to slot under the company’s roof rack. We'd used a version of it in Tanzania and Kenya several times and had been very impressed. Here was a proper outdoor table: welded and braced aluminum legs that folded flat under a top formed and welded from a single sheet of stainless steel. At 29 by 45 inches, the table was large enough for food prep, eating (it seats four snugly), or work, and it weighed a reasonable 23 pounds. She also linked to the Z brackets designed to attach to the Front Runner rack—and then asked, “Could we mount this under the front overhang of the camper?”

I emailed back, “Great idea,” then did some measuring on the camper—plenty of room. Tom at FWC said no problem drilling the composite sheet that forms the bed area of the camper as long as I sealed it well, and certainly no problem with the extra weight: the FWC’s overhang is tested to 1,100 pounds (or, as he and I quipped at the exact same time, “Two average Americans.”).

The table's top is formed, welded at the corners, and riveted to the aluminum frame.

The table's top is formed, welded at the corners, and riveted to the aluminum frame.

When the table arrived it met my expectations and then some. Compared to its cheesy roll-up predecessor it was the Rock of Gibraltar. All the hardware was cadmium-plated and secured with nylocks. The stainless top would be impervious to spills or heat. True, at $285 such features should be taken for granted. Nevertheless it was a relief to consign the blue vinyl table to the Cemetery of Obsolete but Kept Around Forever Camping Gear down in the storeroom.

Exercising due measure-thrice-cut-once caution, I marked and drilled, then veeery carefully countersunk (so the bed’s top section could slide over the bolt heads) three holes for each of the Front Runner Z-brackets from inside the camper. They are designed to hold the table on its narrow ends, but I needed them to hold it on the longer sides, meaning the table would protrude about a half a foot each way.

The bolt heads are countersunk just enough to allow the bed extender to slide over them.

The bolt heads are countersunk just enough to allow the bed extender to slide over them.

The latch mechanism included with the brackets wouldn’t work in our application, so I used a 24-inch-long piece of 1.25-inch aluminum angle iron as an end stop on the passenger side of the truck. I drilled two holes sideways through the frame and top of the table, and inserted a pair of two-inch-long 1/4-inch-diameter clevis pins through them. A pair of hairpin clips holds the pins to the table:

The pins extend through two holes in the end bracket and are secured with two more hairpin clips backed by a rubber washer and a metal washer. I also glued a couple of furniture bumpers on the back of the end bracket, and two flat pieces of rubber gasket on the insides of the Z brackets where the table slides in from the driver’s side of the truck.

The Z brackets came with carpet strips glued along the bottom, so I hoped all the rubber and carpet would minimize any rattling directly over our heads. My last step was to install a backup latch at the other end, using two of the cunning little Expeditionware Transport Loops sold by Expedition Exchange, plus a Quicklink. (My plan is to try to find a small padlock that will fit through these loops.)

Twelve hours after I finished up, the installation got a good test when we left for a biological survey in the Sierra Aconchi in Mexico, which involved a 230-mile paved approach, then a rough ten-mile climb up a four-wheel-drive trail. On the highway the table created no noise at all. On rough slow pavement with the windows open we could very infrequently hear a barely perceptible oilcan effect over sharp bumps as the table top flexed. On the trail there was zero sound from the table or mount, at least none we could hear over the tire and drivetrain noise.

The completed bracket assembly.

The completed bracket assembly.

Once in camp the table proved just about perfect. There was plenty of room to spread out plant samples, notebooks, bird guides, and binoculars; at a group dinner we covered it with chips and salsa and vegetables, then served the outstanding pizzas Roseann somehow managed to make on the camper’s stove top. One night delivered a torrential rain which bothered the table’s aluminum and stainless steel not at all. Total time to set it up on the first day and stow it on our last morning: about two minutes each.

So, not only did we gain a big upgrade in the quality of our outdoor table, we also gained storage space inside the truck. If you have an overhead camper—or a roof rack—I can recommend the Front Runner approach.

On the other hand, if you have a fondness for blue vinyl, email me.

Addendum: A forum member on Wander the West suggested that the Front Runner brackets could be set up to carry a solar panel in the same spot. Brilliant.

Equipt Expedition Outfitters also carries similar tables from K9 racks, in three sizes.

Front Runner Outfitters is here.

The Transport Loops are available here.

Accessible wonders

Many years ago, while on an assignment for Outside magazine, I was graced with the incomparable experience of viewing Victoria Falls for the first time by walking up to the edge of the drop on Livingstone Island, right in the middle of the mile-wide cascade, after arriving by canoe, just as David Livingstone had almost exactly 150 years before. The breath literally left me; I gasped and very nearly wept at the sight. Only the terror of totally losing my cool in front of my guide kept me halfway composed.

Much more recently—last week in fact—I was graced with another first: driving out of the tunnel on California State Highway 41, the Wawona Road, and seeing Yosemite Valley spread out before me below sweeping clouds and mist. El Capitan rose on the left in an impossible vertical wall; Bridalveil Fall plunged in a gossamer thread on the right.

To paraphrase: The breath literally left me; I gasped and very nearly wept at the sight. Only the terror of totally losing my cool in front of my wife kept me halfway composed.

It was a good lesson in something many of us tend to forget: You don’t necessarily need to travel to Zambia (or fill in the blank) to have a once-in-a-lifetime experience. We were two easy day’s drive from home, and the sum total of our off-pavement excursions to that point had been about 500 yards of dirt road to reach a Forest Service dispersed campsite. Yet that view of Yosemite Valley will forever live in my memory directly alongside that first vertiginous peek over Victoria Falls.

The two natural wonders share more than you might think. Both were “discovered”—i.e. sighted for the first time by a person of European stock—in the mid-1800s, after of course being well-known to the locals for ages. In both cases, the “discoverers” were on profit-driven missions: Joseph Walker was looking for furs when he stumbled on Yosemite Valley, and Livingstone hoped to find a water route into the heart of the African continent. Both sites are now overrun with tourists pursuing, at times, tangent activities that seem utterly superfluous to me: I’ve said frequently that if you view Victoria Falls for the first time and think, Okay, cool—now I need to go bungee jumping off the bridge, then there’s something seriously wrong with your sense of wonder.

Yet the grandeur of both places effortlessly transcends the swarms of humans buzzing around them. Even at Yosemite, we found a trail along the Merced River, under El Capitan, on which in four miles we met two other people. And at Victoria Falls I spent a night camped on Livingstone Island (alone except for an askari), and got up at midnight to see the “moonbow”—a rainbow caused by moonlight shining through the mist of the falling water. Later I was awakened by the sound of foraging elephants, which wade to the island at night to feed.

So maybe I shouldn’t complain that everyone else was off bungee jumping.

The author, alone at dusk on Livingstone Island. The bungee jumpers are off toasting their adventure somewhere.

The author, alone at dusk on Livingstone Island. The bungee jumpers are off toasting their adventure somewhere.

New VDEG imminent . . .

I just received this cryptic note from an unnamed source somewhere in the U.K.:

"Desert Winds Publishing (i.e. Tom Sheppard) is pleased (relieved) to announce to its patient, faithful customers and enquirers – some of whom started the list last July – that VDEG3 (otherwise known as the new, third edition of the 500-page Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide), has been proofed and should soon be available. At the same price as before (36 GB pounds) – and not through Amazon, or ‘used’ at four times that figure. (Postage: UK £5.85; EU £9.50, elsewhere, inc US, £16.00)

‘Relieved’ because the techno-gremlins chose the 11th hour to attack the layout software, calling on the true spirit, tenacity and ingenuity of overlanders to get things back on track. Desert Winds Customer Service Department (i.e. Tom Sheppard) quotes their Chief Proof Checker (i.e. Tom Sheppard) as saying, ‘Yes, quite a few of the pictures are now the right way up and most of the text has been back-translated from the Indo-Iranian zabani-tadjik calligraphy’.

On stage, smartly dressed in a black turtle-neck, Desert Winds’ CEO (yes … ) thanked the small distinguished army of back-order e-mailers for their patience and asked them to keep an eye on the www.desertwinds.co.uk website which Desert Winds Webmaster (you guessed it … ) will be updating very soon."

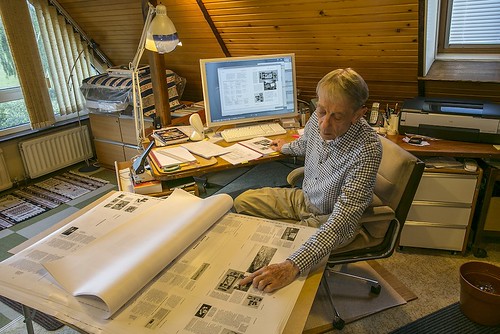

A Desert Winds spokesman, questioned by a lady with a clip-board, said, "No, the actual book won't be as large as the sheets on the table in the foreground."Just in case you've been living under a rock in the Sahara (or are new to the overlanding world, in which case you're forgiven), Tom's Vehicle Dependent Expedition Guide is the bible of overlanding, and a copy should be in the library of anyone remotely interested in vehicle-dependent travel. It is, quite simply, superb in its authority, scope, and humor (i.e. humour), and is the standard by which all other books on the subject are and always will be judged. The fact that it can (and can only) be purchased directly from the writer/publisher/proof checker/customer-service representative is a lovely bonus in this day of Amazon.com facelessness. Of all the high-quality and/or indispensable items I try to discover and recommend on OT&T, you'll thank me for none more than this one. In case you missed the link in the text, it's available HERE.

A Desert Winds spokesman, questioned by a lady with a clip-board, said, "No, the actual book won't be as large as the sheets on the table in the foreground."Just in case you've been living under a rock in the Sahara (or are new to the overlanding world, in which case you're forgiven), Tom's Vehicle Dependent Expedition Guide is the bible of overlanding, and a copy should be in the library of anyone remotely interested in vehicle-dependent travel. It is, quite simply, superb in its authority, scope, and humor (i.e. humour), and is the standard by which all other books on the subject are and always will be judged. The fact that it can (and can only) be purchased directly from the writer/publisher/proof checker/customer-service representative is a lovely bonus in this day of Amazon.com facelessness. Of all the high-quality and/or indispensable items I try to discover and recommend on OT&T, you'll thank me for none more than this one. In case you missed the link in the text, it's available HERE.

A versatile storage box: the Wolf Pack

A pair of Wolf Packs holds tools for a Defender 110 in Tanzania.I have yet to meet the perfect overlanding cargo box. Pelican cases are nearly perfect when contents absolutely, positively must be kept dry and dust-free, thus they are the box of choice for, say, photo and video equipment. But Pelican cases are quite heavy for their volume, and pretty expensive for everyday cargo. Zarges (or the similar Alu-Box) aluminum cases are strong, lightweight, and boast excellent interior to exterior volume, but are even more expensive (although you can consider the expense an investment as they last forever with reasonable care).

A pair of Wolf Packs holds tools for a Defender 110 in Tanzania.I have yet to meet the perfect overlanding cargo box. Pelican cases are nearly perfect when contents absolutely, positively must be kept dry and dust-free, thus they are the box of choice for, say, photo and video equipment. But Pelican cases are quite heavy for their volume, and pretty expensive for everyday cargo. Zarges (or the similar Alu-Box) aluminum cases are strong, lightweight, and boast excellent interior to exterior volume, but are even more expensive (although you can consider the expense an investment as they last forever with reasonable care).

But more economical alternatives always have some fatal flaw. The affordable Rubbermaid Action Packers are excellent for home storage, but their volumetric efficiency is abysmal and they leak if rained on, so you can’t leave them outside the vehicle when camped unless they’re under cover. If strapped down too tightly (i.e., properly . . .), they collapse. Lower-priced alternatives are even worse.

Several years ago in Tanzania I discovered the plastic ammunition cases used by the South African military, now commercially produced and known widely as Wolf Packs. They’re moderately sized and so easy to arrange in a cargo bay, completely rainproof and reasonably dustproof, and vertical-sided to avoid wasted space (except for hollow corner pieces). They stack securely for convenient storage at home. The Wolf Packs suffer from poorly designed latches—those familiar with them will call that a hilarious understatement— and the lids flex more than I’d like when called upon to do duty as a step, but otherwise they are sturdy, versatile, and sport a certain exotic flair given their origins. Front Runner Vehicle Outfitters is now a U.S. distributor, and for $40 each you can justify several—trust me, you’ll find uses for all you get. We have six, and just glancing around the shop I can see uses for another six. Or ten.

We found that a pair of Wolf Packs stacks and straps down perfectly in the shower grate of the JATAC, under the dinette table. Another rides near the door, and holds all the items we use for pitching camp: drain hose for the galley sink, leveling blocks, guylines and stakes for the awning, etc. I sourced some 1/4-inch thick aluminum diamondplate and fabricated steps for the lids of two of them, attached with small stainless bolts; the three now form a perfect staircase to access the camper when we’re parked.

I also keep two in the back of my FJ40. One holds recovery gear; the other contains a small stove and cook kit, water, and other odds and ends to make an emergency camp or an impromptu picnic.

A pair of Mac's Tie-Downs anchor plates and rings, bolted through each side of the dinette seat box, provides anchors for the ratchet strap that secures the boxes.

A pair of Mac's Tie-Downs anchor plates and rings, bolted through each side of the dinette seat box, provides anchors for the ratchet strap that secures the boxes. When not needed, the ring detaches instantly.

When not needed, the ring detaches instantly.

Front Runner's website is here. They also sell improved steel latches.

The analog iPhone

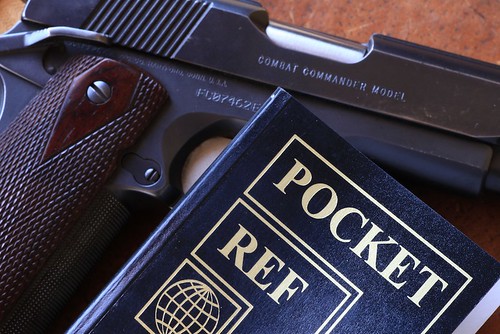

Ready for the bio-apocalypse: a steel-framed handgun and the amazing Pocket Ref

Ready for the bio-apocalypse: a steel-framed handgun and the amazing Pocket Ref

In the speculative-fiction novel Directive 51, author John Barnes postulates an alarmingly plausible near-future in which all plastics, synthetic rubbers, and oil-based fuels have been destroyed by maliciously created self-replicating nanobots and bioengineered microorganisms. All modern communication, transportation, and just about everything else is brought to a halt, and the world is plunged into chaos. The most advanced technology possible peaks at steam engines and vacuum tubes. The book is so believable that Roseann, normally a both-feet-on-the-ground skeptic, mentioned casually after reading it, “You know, it wouldn’t hurt to have a few cases of canned vegetables stored here . . .”

Given our remote home site, dependable well, and abundant wildlife (not to mention free-ranging cattle), we’d be in better shape to survive a bio-apocalypse than 99 percent of the U.S. population. And I feel about 99 percent better equipped to do so since my friend Bruce handed me a copy of Thomas Glover’s Pocket Ref.

I’ve used various one-subject pocket references before (wiring, plumbing), but this tiny 864-page book covers an array of subjects that is simply stunning. Look through the index and pick an uncommon letter—say, W. Now pick one entry out of the 31 listed under W—say, weather. Glover’s Pocket Ref will tell you the following things about weather: Beaufort wind scale; cloud types; cold water survival time; dew points; Fujita-Pearson tornado intensity scale; heat/humidity factors; hurricane intensity scale; ice thickness safety; weather map symbols, and wind chill factors. Over in the Fs, under formulas, you’ll find a staggering 105 entries, from Ohm’s law to antenna length to load on a wire rope or sling to sound intensity to voltage drop vs. wire length, diameter, and current.

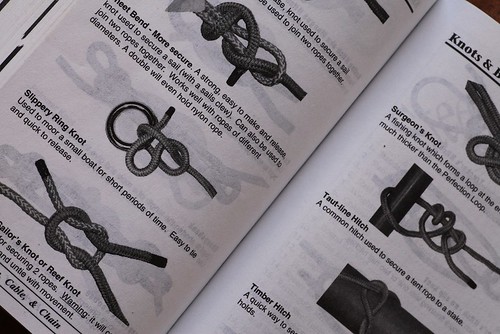

Knots will still work - but better stock up on sisal rope.Other entries: knots—lots of them—treatment for a sucking chest wound; steel tubing specifications; maximum floor joist spans; simple and compound interest factors; area formulas, solvent types; and I could go on for another 863 pages. Need to calculate how much water is left in a cylindrical tank of known diameter and length? No problem. Need to know the rank of the uniformed military personnel who show up after the apocalypse to declare martial law? No problem. Do you have a hard time remembering the geologic time scale (did the Miocene or the Pliocene come first?)—no problem. I can now quickly figure the BTUs available in a cord of Douglas fir, or the clamping force possible with a 15mm 8.8 bolt, or the proper hand signals for a crane and hoist operator. Amazing.

Knots will still work - but better stock up on sisal rope.Other entries: knots—lots of them—treatment for a sucking chest wound; steel tubing specifications; maximum floor joist spans; simple and compound interest factors; area formulas, solvent types; and I could go on for another 863 pages. Need to calculate how much water is left in a cylindrical tank of known diameter and length? No problem. Need to know the rank of the uniformed military personnel who show up after the apocalypse to declare martial law? No problem. Do you have a hard time remembering the geologic time scale (did the Miocene or the Pliocene come first?)—no problem. I can now quickly figure the BTUs available in a cord of Douglas fir, or the clamping force possible with a 15mm 8.8 bolt, or the proper hand signals for a crane and hoist operator. Amazing.

A reference book such as this shouldn’t be entertaining—its mission is to promulgate information. But it’s fascinating to simply browse through the Pocket Ref and see what you can learn. Take my advice: Buy one and just toss it in your glove box—if you come out one morning and find your tires have melted into blobs of bio-slime, you’ll be ready to face the future.

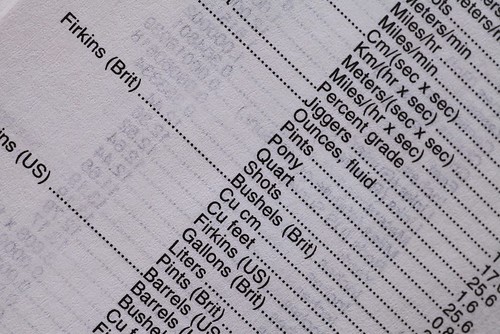

If someone in the New World wants to sell you a firkin of home-brew, you'll want to know just how much that is.

If someone in the New World wants to sell you a firkin of home-brew, you'll want to know just how much that is.

Available on Amazon—as long as Amazon still operates . . .

A proper camp breakfast

GSI Pinnacle griddle on the Snow Peak large Pack and Carry Fireplace with bridge attachment.

GSI Pinnacle griddle on the Snow Peak large Pack and Carry Fireplace with bridge attachment.

Hickory-smoked bacon sizzles on a griddle. The fat pools, spreads, and infuses eggs scambling in butter nearby.

Did your salivary glands just twitch? Of course they did. Any vegans reading this—you had the same reaction. Oh, you might suppress it, pretend it didn’t happen, but somewhere deep down your atavistic omnivore is beseeching you to reject dietary self-flagellation and embrace your rightful place in the food chain.

We all know that eating bacon and eggs on a daily basis is probably not a wise habit—and besides, it wouldn’t be a treat then. But there’s no harm in indulging on a camping trip. Imagine: Dawn breaks over distant peaks, a breeze stirs pine trees overhead, blue jays greet the new day with a raucous chorus, and you stand over a fire with a cup of coffee, inhaling the scent of . . . frying tofu? C’mon.

To do bacon and eggs—and many other proper camping dishes—correctly it’s nice to have a griddle. At home we use cast iron, but that’s a bit heavy for a mobile kitchen when you consider its specialized niche. So we recently tried the Pinnacle Griddle from GSI Outdoors. It’s aluminum and just a bit over two pounds, yet offers a generous 10 by 18-inch cooking area surrounded by a grease moat. The surface is some non-stick space-age stuff—which we eschew at home but which is nice for cleaning up with a limited water supply. The back is hard-anodized (GSI offers a non-anodized version called the Bugaboo).

That one-and-a-quarter square foot size is perfect because, a) when we do eat bacon and eggs we eat a lot, and, b) because it fits nicely over our large Snow Peak Pack and Carry fireplace. (Snow Peak makes a cast iron griddle insert for their fireplace bridge, but it's ridged, and suitable only for cooking meat; we also use our griddle for pancakes and flatbreads.)

The grease moat keeps excess grease off the main cooking area. On the Snow Peak fireplace bridge, you can carefully slide the griddle to the side and pour off excess into a container.

The grease moat keeps excess grease off the main cooking area. On the Snow Peak fireplace bridge, you can carefully slide the griddle to the side and pour off excess into a container.

Cooking over mesquite coals accomplishes two things. First, it adds to the atmosphere of the experience; second, it keeps that atmosphere out of the camper, where too much bacon grease and smoke too often would not be good for the canopy and upholstery. The griddle also fits in the fireplace’s (insanely obtuse) carrying case.

The Pinnacle Griddle’s aluminum is fairly thin, which means low heat will suffice, but not so thin that there were hotspots—it heated and cooked evenly for both bacon and pancakes. However, the surface of ours also came slightly convexly warped, so that an egg cracked in the middle would sort of elongate toward the edge until corraled with a spatula. I plan to see if it will flatten, using some heavy boards and judicious pressure.

Cooking eggs and tortillas in the bacon grease. Can life get any better?

Cooking eggs and tortillas in the bacon grease. Can life get any better?

In the meantime, it’s working just fine—and we’ve successfully subverted several vegans at group camps.

Visit GSI here.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.