Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

A proper knife

The knife was almost certainly mankind’s first manufactured tool into which we put not just craftsmanship, but artistry. First (after poking around that funny black monolith) we simply grabbed handy tree limbs for clubs, or rocks suitable for smashing things. Then, about 2.5 million years ago, a perceptive hominid noticed a river rock with a naturally chipped edge that proved much superior for cracking open bones or the skull of a rival. Jump ahead a million years, and his Homo erectus descendants had learned how to flake quartzite and basalt into sophisticated and sharp bifaced hand axes. Next came flint and obsidian spear points and arrowheads, with finer and finer workmanship. Somewhere along the line a smart craftsman lashed a bone or antler handle to his skinning blade—and from that point forward the design of the knife strayed not a bit except for the steady evolution of material and the eventual innovation of folding blades. The knife became our single most indispensable personal-carry tool, and stayed that way right up to the advent of the iPhone.

When I was younger, if you went outdoors, whether for hiking, backpacking, canoeing, car camping, hunting—whatever—you carried a fixed-blade sheath knife, the direct descendant of that flint-and-bone progenitor. It was axiomatic that the knife would be your primary tool for dozens of tasks: cutting rope and webbing, field-dressing fish or game, cooking and eating, carving, you name it. It was also axiomatic that a fixed-blade knife would be the best choice for those tasks, given its superior strength and control over a folding knife, and easy one-hand accessibility right there at your belt. I got my first sheath knife when I was seven, as did my best friend, and neither we nor neighbors who saw us carrying them around our rural community thought a thing of it.

Not any more. With the exception of increasingly rarified circumstances and company, wearing a sheath knife today—even if you’re an adult—seems to be considered, at best, ostentatious, and at worst an aggressive “statement” that indicates you might also support private ownership of tactical nuclear weapons. I’ve related before the story of an acquaintance who wore one into a West Coast coffee shop and was accosted by a woman demanding to know what he was doing “with that weapon in here.” He swears he replied, “Lady, you should hear what the voices in my head are telling me to do with it.” A seven-year-old carrying a sheath knife today? He would probably be remanded to Social Services and his parents jailed.

I say we fight back—figuratively speaking, of course. If you own a fixed-blade knife and have ever felt too self-conscious to carry it, and then had to perform some task with a pocket knife clearly too small for the job, strap that thing on next time. Don’t own a fixed-blade knife? Go get one, learn how to sharpen it properly, and carry it proudly.

There are undoubtedly thousands of fixed-blade knife (let’s say FBK from now on) models marketed as suitable for general field work, but you can broadly divide their design philosophy in two: handy designs with plain (i.e. non-serrated) edges and blades between three and five inches in length, and much larger, heavier tools with six, eight, even ten-inch blades (often nearly 1/4-inch thick at the spine), that supposedly can also be used for chopping, hammering, and, if you believe some of the ads, hacking your way out of your downed F16’s cockpit, spearing caribou after securing the handle to a stick with your unraveled paracord bracelet—and, of course, fighting off zombie hordes.

Gee, I guess my prejudice is showing already.

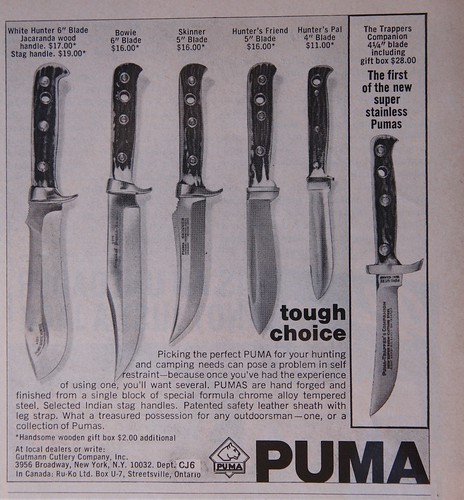

For decades, my FBKs were all the former style, from that first blade in second grade to the Buck Personal that was the first knife I bought myself, to the dream knife I couldn’t afford then but purchased at a usurious collector price decades later: the near-mythical (well, among knife wonks anyway) Puma Trapper’s Companion—$32 in 1970; $400 30 years on.

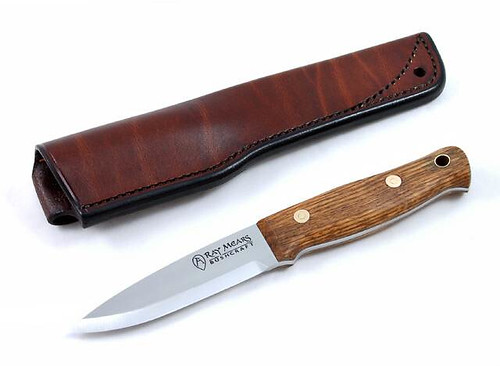

A classic Puma Hunter's Friend, above, and the even more classic Trapper's Companion, below. (Sadly, Puma knives aren't what they used to be; those made prior to 1995 or so are the best) Along the way I discovered perhaps the most versatile style of all: the so-called bushcraft knife, defined by the Woodlore, which was designed by Ray Mears in 1990 and is now copied by knifemakers everywhere. Like Ray himself, the Woodlore is an unassuming thing with a 4.25-inch, spear-point blade. It employs what’s known as a Scandinavian (“Scandi”) grind: The blade holds its thickness from the top (spine) most of the way toward the edge, which has a single bevel extending quite high up each side.

A classic Puma Hunter's Friend, above, and the even more classic Trapper's Companion, below. (Sadly, Puma knives aren't what they used to be; those made prior to 1995 or so are the best) Along the way I discovered perhaps the most versatile style of all: the so-called bushcraft knife, defined by the Woodlore, which was designed by Ray Mears in 1990 and is now copied by knifemakers everywhere. Like Ray himself, the Woodlore is an unassuming thing with a 4.25-inch, spear-point blade. It employs what’s known as a Scandinavian (“Scandi”) grind: The blade holds its thickness from the top (spine) most of the way toward the edge, which has a single bevel extending quite high up each side.

Knife edge grinds. Courtesy Off the Map custom knives.

Knife edge grinds. Courtesy Off the Map custom knives.

The Scandi grind is immensely robust—bushcrafters use these knives to split two-inch-thick limbs lengthwise by “batoning,” that is, holding the edge of the blade against the end of the limb, and using another length of limb to hammer the knife straight down. The technique even works across the grain. Yet the Scandi grind can be given a razor edge; that broad bevel makes it easy to index the blade on a simple sharpening stone if you don’t have a sophisticated system such as the Edge Pro. If the grind has a weakness, it is for exceptionally fine slicing—that broad bevel acts as a wedge rather than a scalpel. Scandi blades make lousy cheese cutters.

The current Ray Mears knife has a durable English oak handle.

The current Ray Mears knife has a durable English oak handle.

The genuine Woodlore knife rightfully carries a substantial premium given its provenance; high-quality copies are available for less for those who don’t need or can’t afford the Woodlore signature. I have a bushcraft knife nearly as well-known in the community: a stout design called a Skookum Bush Tool, made in Whitefish, Montana by Rod Garcia. Rod enhanced the Woodlore pattern by adding a flat steel back on the handle, which is welded to the full-tang blade and enables the user to hammer this thing point-first into, well, anything that needs a knife hammered into it.

Many other knives parallel the bushcraft style, from the astoundingly underpriced ($18) and overperforming Mora Clipper to custom models made with exotic steels and even more exotic hardwood scales (handles), which can easily top $500. As an all-around field knife the bushcraft design is hard to beat, although flat-ground and hollow-ground blades also work very well for most tasks, and better for some.

Top to bottom: Mora Clipper, Helle Eggen, Wood Bear, Skookum Bush Tool, Helle Temagami.

Top to bottom: Mora Clipper, Helle Eggen, Wood Bear, Skookum Bush Tool, Helle Temagami.

In the last few years an entirely different style of FBK has become increasingly popular, especially among the survival community (by which I mean people interested in survival skills, not the guys who hole up in the Idaho mountains with “Bo Gritz for President” posters tacked up in the fallout shelter). The style is frequently referred to even among its proponents as a “sharpened pry bar.” Forget handiness—these knives are massive, and built to withstand laughable abuse—one popular demonstration involves chopping through a concrete block, another, repeatedly stabbing though a car door. The fact that they have a cutting edge seems secondary to the astounding breadth of ancillary destructive purposes to which one is assured they can be directed. The names of these things echo their marketing: Compare the quasi-Elvish “Woodlore” with the “Swamp Rat,” the “Black Legion,” or the “Extreme Survival Bowie.” And, yes, there is an official “Zombie Killer,” with a, not making this up, “Toxic Green” handle.

I picked up one of the early examples of this genre, the Gerber LMF-2, at a trade show some years ago, and immediately put it down. The knife was heavy and unbalanced, and its “tactical” sheath, complete with de rigueur mid-thigh mounting straps, weighed more than the knife. Similar models from other makers impressed me no more, and I dismissed the entire concept as a short-lived fad.

Wrong. The LMF-2 is still around, and has been challenged by even more bloated competitors. So I decided to give the concept a fair chance, and procured an LMF-2 as well as a Ka-Bar/Becker BK-2. I used each for several days around our place and in the surrounding desert, on tasks for which I’ve been using much smaller knives for tens of years.

Top: the Becker/Ka-Bar BK-2; bottom, the Gerber LMF-2.

Top: the Becker/Ka-Bar BK-2; bottom, the Gerber LMF-2.

And . . . I still don’t get it.

The LMF-2 has that most worthless of blade styles, half plain and half serrated—which leaves neither enough room to do its job. The (reasonably sharp) plain edge is out at the end, is mostly curved, and is barely three inches long despite this knife’s 10.5-inch overall length and three-quarter-pound weight (LMF, perversely, stands for “Lightweight Multi-Function”). The blade on my Swiss Army knife is only a half-inch shorter. The Gerber’s serrated section, as with all such edges, is virtually impossibly to sharpen in the field—although the nifty sharpening slot in the LMF-2’s plastic sheath is okay for touching up the plain edge. By way of comparison, one of the best field knives I own, a Helle Temagami, weighs just 5.4 ounces despite 4.5 inches of usable blade.

The knife is undeniably stout. The pointed pommel, I’m sure, could “egress through the plexiglass of a chopper” as Gerber claims, or be employed for an occiput strike on a sentry—which all of us are sure to need to do at some point in our lives. In fact, as kit for a combat pilot, the LMF-2 might not be a bad tool at all. But for any kind of regular use in the field—including survival—the LMF-2 has all the wrong answers to the questions that are most asked in such situations. It even touts the ultimate lunacy for a survival knife: three holes in the handle so you can “lash it to a stick and make a spear.” Lord spare us from such nonsense.

However. If I thought the Gerber was unwieldy, the Ka-Bar/Becker BK-2 makes it look like a surgeon’s scalpel from Porsche Design.

I’m convinced the designer of the Becker had an LMF-2 for comparison, and simply decided that whatever it had, the BK-2 was going to have more. So the Gerber weighs 12 ounces? This knife is going to weigh a pound. The Gerber’s blade is a fifth of an inch thick? Ha!—we’ll make ours a quarter of an inch thick. And then add a bit.

The result is one of the most cartoonishly overbuilt and comically awkward knives I’ve ever owned.

Seriously? The monstrous BK-2 next to the far more practical Temagami.

Seriously? The monstrous BK-2 next to the far more practical Temagami.

The makers tout the Becker’s chopping ability—the supposed payoff for the weight and bulk—but in fact it’s a lousy chopper. Despite the massive blade, it’s still handle-heavy, and the edge is not long enough to gain the speed and momentum even a lightweight machete can achieve. There is no reason—not one—to make a knife blade a quarter of an inch thick, except to one-up someone else’s blade. No user could ever put enough leverage on this knife to bend, much less break it. It is simply dead weight. Its sole positive feature is that it blessedly dispenses with serrations (or, worse, saw teeth), but the spine is so thick and the knife so heavy that normal cutting operations—the kind you need to do 99 percent of the time even if you are a combat pilot—become ham-fisted struggles, like tapping in finish nails with a three-pound sledge.

The Becker dwarfs a lovely model from knifemaker Lynn Dawson, with a hollow-ground blade just three inches long. Yet I field-dressed a whitetail deer with the Lynn knife . . .

The Becker dwarfs a lovely model from knifemaker Lynn Dawson, with a hollow-ground blade just three inches long. Yet I field-dressed a whitetail deer with the Lynn knife . . .

. . . and the Lynn sports some nice file work on the spine. Tough doesn't have to be ugly.

. . . and the Lynn sports some nice file work on the spine. Tough doesn't have to be ugly.

Believe it or not, the LMF-2 and BK-2, with mere five-inch blades, are on the small end of their phylum. The ESEE Junglas (pronounced hoonglas) sports a 9.75-inch blade—actually almost long enough to be credible as a chopping tool, but with a concurrent reduction in practicality to near zero for any normal cutting tasks (To be fair, ESEE makes some entirely practical smaller models as well).

Let’s put together some numbers here. For the weight of a BK-2 one could carry a Helle Temagami, or a Woodlore clone, or any number of other fine, compact, well-balanced—and, dare I say, beautiful—cutting instruments, plus a Gerber folding saw, plus a lightweight sharpener. You’d have a vastly superior knife and a better, safer way to cut through larger limbs than hacking away with that “sharpened prybar.”

Ah, but what about the scenario the armchair experts like to debate ad nauseum: You’ve somehow been stupid enough to be caught out in the wilderness with nothing but a single knife. No saw, no machete, no matches, no tent, no iPhone. You need to survive with that one tool.

Give me the bushcraft knife any day.

Most of the tasks you’ll need to do to stay alive in such situations—building a shelter, making fire, perhaps constructing snares or deadfalls—are far more easily accomplished with a modestly sized blade. You won’t need branches larger than two inches in diameter for a lean-to, and those are easily cut with a bushcraft knife and, if needed, a baton. (Batoning is also infinitely safer than chopping; need I mention that severing a major artery would be inconvenient at this point?)

The rest—hearths and drills for a friction fire, snares, field-dressing game—require a deft touch with a blade. You’ll operate more quickly, surely, and with less energy expenditure if you have a knife as deft as the task.

And back in the real world? No contest. I got annoyed just carrying the BK-2, much less using it. It was a major relief to get back to my normal knives.

If you’re traveling by 4WD vehicle, or even by motorcycle where weight is much more of a concern, there’s simply no reason to consider dragging along an awkward, heavy knife that tries to take the place of two or three tools, even if the concept worked. Buy a good, sensibly sized FBK, and carry a folding saw, hatchet, or small axe for larger cutting tasks (for a really nice combination look HERE). You’ll be more effective and safer.

Besides, I hear axes work better on zombies anyway.

Edit: Found an old ad. The Trapper's Companion originally listed for $28, not $32. I should have got a second job and bought 20 of them then.

Edit: Found an old ad. The Trapper's Companion originally listed for $28, not $32. I should have got a second job and bought 20 of them then.

Another edit: Found this on a scouting site in an article about knives. I'm speechless:

I am a scout leader (aka Scout master) with Scouts Australia. Here in Western Australia this is a copy of our Policy and Rule regarding knives

K1. KNIVES. K1.1 Statement.

The Scout Association of Australia, Western Australian Branch (“the Association”) strongly recommends that all members be aware of, and exercise all possible care in, the use of knives.

K1.2 A sheath knife should not be worn by any member on, or participating in, Scouting activities.

K1.2.1 The wearing of a sheath knife is considered being contrary to State Law, particularly where the knife is displayed in a public place such as a street or a point of gathering.

K1.3 The use of a good quality pocket knife is strongly recommended and the use of such is encouraged under circumstances by all members on, or participating in, Scouting activities.

I'm going to go strap on every sheath knife I own and find a coffee shop . . .

Links:

Woodlore, Helle, Mora, Wood Bear, Skookum Bush Tool, Off the Map, Ka-Bar, Gerber

For interesting Puma lore, and occasional knives for sale, go HERE.

A follow-up: Patrick York Ma of Motus and I apparently had a bit of a mind meld a few weeks ago. Read his piece on knives here.

Tire pressure

The load index 109, on the right, is used with the load range to calculate optimum pressure.

The load index 109, on the right, is used with the load range to calculate optimum pressure.

A reader, Christian, sent in this comment to my recent post The physics of tires and lifts:

I have a related question that might warrant its own post. Is there a formula for finding your optimum tire pressure? Sounds simple enough. Most “experts” just say to check the owner’s manual. I’m skeptical because my new F150 has a front/rear weight ratio of 60/40, yet Ford recommends a higher pressure in the rear (60 rear, 55 front). I'm assuming this is in anticipation of a full payload but it seems to me that the correct pressures should be based on actual axle loads and tire volumes (i.e. a larger, wider tire will need lower pressures but the front/rear ratio should remain the same). Off-road pressures will be much lower (and highly variable) but again should utilize the same front/rear ratio. Does this sound right?

Christian, common sense is leading you in the right direction.

Tire pressures recommended by vehicle (and tire) manufacturers have varied significantly over time, often depending more on what they perceived as their customers’ priorities than on efficiency or even safety. In the days of Ford Galaxies and Buick Rivieras (and 32 cents-per-gallon gas), it was all about ride comfort, and recommended tire pressures hovered in the 20s. Today, fuel efficiency is the name of the game, and pressures are much higher, as you found on your F150. However, as you noted, the manufacturer invariably lists only a single figure. Especially in the case of a pickup, loads are likely to vary tremendously. Proper pressure for a light load will be inadequate for a heavy load, and proper pressure for a heavy load will be excessive for a light load and will cause premature tread wear in addition to a bouncy ride.

There are a couple of good ways to determine proper tire pressures for your vehicle to compensate for varying loads. First is an inflation/load chart. Why these aren’t front and center on all tire company websites I have no idea—most specification charts list only maximum load—but if you search deeply enough you can find them. We’ve posted one used by Discount Tire HERE.

An inflation/load chart uses the load index listed on the tire’s sidewall (after the sizing information), and the load range (C, D, E, etc.) to determine an optimum pressure. Much better than a single figure, obviously. To exploit this information fully, however, you need to know how much weight is on each tire. You can calculate that closely by finding a commercial scale the weighing each end of your vehicle, then dividing each by two. If you have a slide-in camper you remove for commuting in between trips, you can either make two trips to the scale or calculate the added mass of the camper if you know its dry weight. With that information in hand, you can cross-reference the chart to arrive at a very useful figure.

A simpler way to determine optimum tire pressure (as well as to double-check the chart method) is by “chalking.” Use a piece of bright chalk to mark a thick line directly across the tread of each tire. Drive a few hundred yards on pavement (preferably in a straight line) and look at the line. If it is wearing off evenly, your tires are correctly inflated, as the tread is bearing the load uniformly across its width. If the center of the line wears off more quickly the tire is overinflated, and if the edges wear off first it is underinflated. You might have to use paint rather than chalk to ensure the line doesn’t wear off too quickly.

Both these methods are designed to calculate road pressures. Once you have them figured, you can use them to arrive at starting points for airing down on off-pavement routes. A 30 to 40-percent reduction in pressure is usually enough to lengthen the tire’s footprint effectively, increasing traction and reducing impact on the trail as well as attenuating bounce over washboard and rocks. For deep sand one would drop quite a bit more than that, of course.

This might seem like more trouble than it’s worth to some. But you only need to do the weighing once per vehicle, and then recalculate if you buy different tires. But maintaining ideal tire pressures—as opposed even to just adequate—will significantly increase tread life, in addition to enhancing every aspect of tire performance.

The physics of tires and lifts

The JATAC with Four Wheel Camper mounted; LT235/85 R16 BFG All-Terrain tires, Boss air bags on stock rear springs, Icon shocks at all four corners.

The JATAC with Four Wheel Camper mounted; LT235/85 R16 BFG All-Terrain tires, Boss air bags on stock rear springs, Icon shocks at all four corners.

At the Overland Expo this May, Roseann gave a walkaround of the JATAC to a crowd of about 40 attendees, and throughout the weekend we were frequently approached by individuals and couples who’d seen it displayed or had read about it here, and who had various questions. Most were of the general general how-do-you-like-the-combination sort; many got into specifics of our modifications. But two questions about what we hadn’t done cropped up with interesting frequency:

- “Why didn’t you install a suspension lift?”

- “Why didn’t you install larger tires?”

The short answer to both questions is, “Physics.” The long answer follows.

Our goal in mating a Toyota Tacoma with a Four Wheel Camper was to strike a balance between reliability, durability, capability, comfort, and convenience. The camper provides comfort and convenience; it’s up to the truck to contribute reliability, durability, and capability. Part of the balance is realizing that roughly 1,000 pounds of comfort and convenience has potentially significant effects on the other three.

Reliability of the Tacoma should be a given. The Identifix rating for the current generation Tacoma shows five stars for every year since 2006. Our 2000 Tacoma was the single most reliable vehicle I have ever owned: In 160,000 miles we did nothing to it except scheduled maintenance. Not one repair. Even my faithful 1973 FJ40 couldn’t match that record at that mileage (burned exhaust valve at 150,000). It’s still too early to pass judgement on the new truck, but statistically we should be able to look forward to a similar experience.

Durability should be a given as well, certainly in terms of the drivetrain. Engines in general are lasting longer these days (200,000 miles really is the new 100,000), thanks to better materials and more precise machining capabilities—and Toyota engines, transmissions, and differentials stand out even among these higher standards. I’m still not completely sold on the composite bed or the open-channel back half of the chassis, but my master Toyota mechanic friend Bill Lee keeps telling me to stop fretting.

That leaves capability, which is what most people are attempting to augment with suspension lifts and larger tires (unless they’re strictly after the looks).

The Tacoma as we got it, with stock P245/75R16 all-season tires (30.5" diameter). It’s true that a mild suspension lift will increase chassis ground clearance and—if properly specced for the vehicle—improve suspension travel and compliance, enhancing both ride comfort and the ability of the truck to keep all four wheels on the ground for better traction when traversing rough terrain. Larger-diameter tires also increase ground clearance, and provide a fractionally longer footprint that can enhance traction.

The Tacoma as we got it, with stock P245/75R16 all-season tires (30.5" diameter). It’s true that a mild suspension lift will increase chassis ground clearance and—if properly specced for the vehicle—improve suspension travel and compliance, enhancing both ride comfort and the ability of the truck to keep all four wheels on the ground for better traction when traversing rough terrain. Larger-diameter tires also increase ground clearance, and provide a fractionally longer footprint that can enhance traction.

But there is a price to be paid for those gains. Let’s look at tires first.

A larger tire weighs more than a smaller tire—common sense, obviously, but the range of effects of that weight are not all obvious. As an example, let’s compare a couple of BFG All-Terrains. The LT235/85 R16 ATs we recently installed on the Tacoma are 31.7 inches in diameter, and weigh 46.4 pounds each. If we decided to go up in diameter a very modest 1.5 inches, to a 295/75 R16 AT at 33.2 inches diameter, that tire weighs 57 pounds. That’s ten pounds of unsprung weight (a term that refers to weight not supported by the suspension, including wheels and tires, brake components, bearings, axles, etc.—think of everything that goes up and down under the vehicle when you hit a bump) to gain 3/4-inch of ground clearance. Adding ten pounds to a vehicle’s unsprung weight has a far more dramatic effect on ride and handling than adding the same amount to the sprung mass. The springs and shock absorbers have to react to that weight over every imperfection in the road.

But that’s not the only effect. The mass of a larger tire (and, if fitted, a wider wheel) places additional stress on the braking system and retards acceleration—and the tire’s rotational moment of inertia, which increases with the square of diameter if I’m remembering my physics correctly, affects both as well. A 2003 study of the effects of suspension lifts and larger tires showed that going from a 32-inch tire to a 35-inch tire resulted in a ten percent loss in brake efficiency. That’s a significant effect on your ability to stop quickly.

Finally, a larger-diameter tire affects gearing. For example, at a constant 65 mph, the engine in a vehicle equipped with 4.11 differentials, a 1:1 top gear in the transmission, and 31-inch tires will be turning approximately 2900 rpm. With 33-inch tires the same vehicle will be turning 2720 rpm. That might sound like a good thing—after all, lower engine speeds should equate to better fuel economy, right? Unfortunately, it’s rarely so. You’re messing with a torque curve that the factory knows inside and out, and you can bet they’ve calculated the final drive ratio to optimize that curve. The losses associated with the extra mass and rotational inertia will almost certainly cancel out any possible gains in highway mileage with increased city consumption, as shown by numerous controlled studies.

Going up in tire diameter will also hurt your low-range performance, since the vehicle will be traveling faster at any given engine speed. That will reduce your control in low-speed situations. Few vehicles these days come with low-range transfer-case gears I consider low enough anyway (although the now nearly ubiquitous automatic transmission helps), so compromising what’s there makes little sense.

Why not simply regear the differentials to compensate, as dedicated rock crawlers do when they install those big 40-inch-plus tires? In terms of correcting the overall final drive ratio, it works—but at the expense of differential strength. The problem lies in the pinion gear, the only gear of the two major pieces in the differential one can change in size to alter the gearing (the ring gear is limited by the size of the differential case itself). So when one goes from, say, a 4:1 differential to, say, a 5:1, the pinion gear is essentially reduced in size from one fourth the size of the ring gear to one fifth its size. Additionally, the smaller pinion gear means that fewer teeth will be in contact between the two gears at any one time. And you still face the inescapable physics of accelerating and decelerating a larger, heavier tire. Breaking a diff on a local rock-crawling trail would be a pain. Breaking a diff on the Dempster Highway—or on the Dhakla Escarpment—would be a major pain.

What about suspension lifts? Done correctly (i.e., with properly rated springs and shocks; no eight-inch shackles or lift blocks), and kept within reasonable limits (two to four inches on most vehicles, especially those with independent front suspension), the biggest disadvantage you’re likely to encounter is increased drag and reduced fuel economy. True, your center of gravity will be fractionally higher, but the increased ground clearance for approach, breakover, and departure angles is probably a fair tradeoff. However, on a truck with a cabover camper, overhead clearance becomes an issue. On some of the biological surveys we do in Mexico, trees hang low enough over the approach trails to be a concern even with a stock suspension.

All this might sound like I’m dead set against straying at all from factory suspension heights and tire sizes. Not at all—but doing so does involve compromise, and the further one strays from stock tire sizes and suspension heights, the more compromises involved. As long as you’re aware of the issues, consider the cost/benefit ratio, and don’t go all monster truck, your approach might well be different than ours yet still effective for you. Consider my FJ40, which has both a mild (two-inch) Old Man Emu suspension lift and tires (255/85R16 BFG Mud-Terrains) that are at 33 inches significantly larger than the teeny factory-supplied 29-inch tall Dunlops. I settled on the combination after years of driving the vehicle stock, and with careful consideration of the drivetrain. The FJ40’s rear axle shafts are the same diameter as those in a Dana 60 (which is installed on 3/4-ton pickups), and its ring and pinion gear are nearly as stout—I’m on my original differentials at 320,000 miles. The front Birfield joints are not as bulletproof, but very few FJ40 owners have problems with them unless they’re running 35-inch or taller tires with power steering (my steering is powered by how hard I can turn the wheel). Mechanic-friend Bill once said that if I ever broke a Birfield with my setup he’d drive out and replace it for free. He hasn’t yet had to pay up on that offer. Also, significantly, the 1973 FJ40 came from the factory with drum brakes on all four wheels. I’ve installed discs all around, so my braking system is far superior to the factory setup even with the larger tires.

With a two-inch OME suspension, 255/85/16 tires are a good fit on the FJ40. Rear tires tuck into fender well without rubbing when springs are fully compressed.

With a two-inch OME suspension, 255/85/16 tires are a good fit on the FJ40. Rear tires tuck into fender well without rubbing when springs are fully compressed.

Given our intended use of the JATAC, which will combine long trips on pavement, extended mileage on dirt roads (we drive seven miles of dirt road just to get home), frequent use on four-wheel-drive trails, but little or no intensive rock crawling/mud surfing unless we find ourselves in a situation that requires it, we elected to stay with a very moderate size increase on the tires (to those 235/85/16 BFG All-Terrains), and stock suspension height. I leveled the back end of the truck with a set of excellent Boss air bags over the stock springs, and the shocks at all four corners are adjustable Icons with remote reservoirs.

Boss air bags augment the Tacoma's stock springs to maintain a level stance with varying loads.

Boss air bags augment the Tacoma's stock springs to maintain a level stance with varying loads.

We still plan to augment the JATAC’s off-pavement capabilities in other ways. First, we’ll be adding a locker for the rear differential—after tires (maybe even before) the absolute best way to enhance traction in difficult situations. Second, we’re working with Pronghorn Overland Gear on a prototype aluminum winch bumper. Pronghorn has just introduced an extremely high-quality modular bumper system for the Jeep Wrangler; the Tacoma is next on their list, and if the result is as good as the Wrangler version it will be good indeed—improbably light yet strong enough to take the the most demanding stresses of winching without complaint*. The Pronghorn bumper will also be compatible with the Hi-Lift jack already mounted to the Four Wheel Camper (see here). With a winch mounted up front we’ll have a backup plan if our tires and locker (and piloting) can’t get us out of a sticky situation. Finally, Pronghorn will also be developing a full aluminum skid-plate system for the Tacoma, so if our moderate ground clearance proves inadequate now and then, the underside of the truck will be fully protected.

As with many trucks employing independent front suspension, the lowest spot on the JATAC's undercarriage is the rear differential, visible here beneath the front factory "skid plate." The diff's placement in the center of the axle means it's more likely to drag on high-crowned trails. Larger-diameter tires would increase this clearance fractionally; a suspension lift would not.

As with many trucks employing independent front suspension, the lowest spot on the JATAC's undercarriage is the rear differential, visible here beneath the front factory "skid plate." The diff's placement in the center of the axle means it's more likely to drag on high-crowned trails. Larger-diameter tires would increase this clearance fractionally; a suspension lift would not.

This reminds me: I keep meaning to add a set of MaxTrax as well. We were recently on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim after a heavy rain, and the washes in the House Rock Valley had flowed energetically. The first one we came to had subsided to a trickle, but the substrate was still treacherous. The odds were nearly certain we could have crossed with no trouble, but we were a single vehicle with no winch. A stuck truck could have meant hours of digging out, with more rain and flash floods likely. Additionally, beyond this first wash were several larger ones between us and our goal on the rim. So we turned around. A simple set of MaxTrax (or any of several other suitable brands of sand track) would have given us the confidence to take the slight risk.

The JATAC on its modest tires and stock-height suspension might not have the brawny look of a taller sister truck on meatier tires, but we’re convinced it was the right approach for us and our intended uses. But I’ll be honest—if we change our minds, I’ll let you know.

Boss Global is here. Icon Vehicle Dynamics is here. Pronghorn Overland Gear is here. Maxtrax is here.

*Full disclosure: I consulted with Pronghorn on some final design details and proof of concept of their Wrangler bumper system.

Oil change: A simple job . . .

. . . unless you don't get the (separate) O-ring gasket lined up properly on the canister filter cartridge on your 300D. The O-ring is at the top of the filter housing, so I didn't realize it wasn't in correctly until I fired up the engine. It had in fact slipped completely down around the filter, leaving no seal whatsoever.

So this was the sight that greeted me through the windshield as I backed up the slope thinking I was finished. My own little Exxon Valdez. Pulled it back down, re-installed the O-ring properly. Now for some Simple Green and absorbent compound.

Just goes to show that a brilliantly conceived one-case tool kit does no good if you don't use the tools contained therein properly.

JATAC gets an outdoor kitchen

by Roseann Hanson (co-director, Overland Expo)

There's a lot I love about having a stove, sink, and fridge inside a truck camper—all-weather cooking, protection from mosquitoes, and the convenience of a full kitchen (see this article, about our "Just a Tacoma and Camper" setup). But I miss cooking outside. It's more social, and enjoying the views is why we explore and camp. Nothing like sipping a cool drink, tending some thick pork chops, and gazing out over the Grand Canyon while a condor soars overhead . . .

To facilitate outdoor cooking, we sorted out a camp table and awning. Jonathan rigged us a sleek and easy mount for the sturdy stainless steel table from Frontrunner Outfitters (see story here). And although it was initially a tough decision ($800), we invested in a high-quality, quick-deploying Fiamma awning for the starboard side. Importantly, this is also the side for access to the Four Wheel Camper's dual 10-pound propane tanks, since I settled on a propane grill, for convenience and when local fire restrictions or wood availability obviates our Snow Peak portable fireplace grill. My idea was to leave one tank hooked up to the inside stove and hot water heater, and the second tank rigged with a portable grill hose so all we had to do was hook it up and start cooking.

Now all I needed was a portable propane grill that was powerful, not too bulky, high-quality, and functional.

Easier said than done. I looked at many name brands, including Coleman, Char-Broil, Weber, and NexGrill (a sister brand of Jenn-Air). Some had great BTU ratings (the NexGrill boasts 20,000 and has 2 burners with separate controls). Some were clever (the Coleman Road Trip has an integrated stand that scissors down, so you don't need to use up valuable table space). Some were cheap (the Char-Broil at $30 via Amazon—with the savings you could buy a lot of top sirloin . . .). Some were compact (the Fuego Element closes like a sleek clamshell and is just 9x12).

But in the end my eye was caught by the Napoleon PTSS165P portable grill ($189 MSRP), built for the demanding marine environment (you can order very pricey sailboat cockpit mounts for it). Runner up was the NexGrill (model 820-0015, $180 at Home Depot) but reviews on Amazon indicated the finish quality was poor, with some users claiming not all parts are stainless, or were flimsy with sharp edges. The quality of the Napoleon looked so good, I decided to take a gamble on its 9,000 BTUs (compared to twice that for the NexGrill) and single burner control.

The finish quality of the Napoleon is beyond reproach: folded and riveted corners, smoothly finished vent holes, and sturdy (not at all "tinny") 304 stainless throughout.

Details like the high-quality latch and rivets won me over.

The four-inch legs are anchored with stainless bolts, and pivot flush to the bottom for storage. Only complaint: they do scratch the tabletop, so we're going to coat the bases in Plasti-Dip.

The handle stays cool even after long periods of cooking. However, it's on the wrong side for a right-handed person (when grilling, you usually hold a utensil in your right hand and would use your left to open the grill to check cooking progress). The pietzo-igniter stopped working after the first night. The propane regulator is also on this side. The Napoleon only comes with a mount for small 1-pound canisters; we had to buy a 5-foot hose to connect it to our 10-pound tank.

Cooking area is 17.25 x 9.25 and just about perfect for two people. For more food than that, cooking in shifts would be recommended. To get searing temperatures, the instructions recommend lighting the grill and pre-heating for 10 minutes. This did produce temperatueres just right for searing the pork chops. I do wish it had two burners so I could turn one off to create a cooler location for finishing things like vegetables.

The slightly domed lid is vented but very windproof (we cooked two dinners in 10-15 MPH gusts), and its height would allow cooking a small whole chicken or something in a deep-dish pan; you could even bake a cake or low-top bread. There is a slide-out grease trap tray on the bottom, which made clean-up super easy.

The carrying case fits well but its quality is not commensurate to the grill: the fabric is thin Cordura and is poorly sewn (on ours, the inside pocket for the gas regulator pulled out at the bottom), so I'm not expecting it to last as long as the high-quality grill.

We've now used the Napoleon half a dozen times on a 2,800 mile trip, and are overall extremely pleased with the quality. It's also transformed our camping by doubling our "living area" to include a spacious, convenient, shaded outdoor kitchen where we can easily grill salmon steaks, cook lasagna, bake a cake, or turn out bacon and pancakes on a griddle for a small group.

(Awning: Fiamma.com; table: FrontrunnerOutfitters.com or a similar version from K9 racks and Equipt Expedition Outfitters, available in three sizes)

Outdoor Retailer 2013

This was tucked in a far back corner of the main hall. I didn't ask.

This was tucked in a far back corner of the main hall. I didn't ask.

For anyone remotely interested in outdoor gear, the annual Outdoor Retailer show in Salt Lake City, Utah, is an exciting event, overwhelming in the scope and sheer volume of products. If you’re as fascinated by equipment as I am, you’re likely to find yourself humming the tune to Babes in Toyland as you enter the main hall and inhale the scents of Gore-Tex, carbon fiber, nylon, and titanium. Okay, none of those materials really has a scent, but you get my meaning.

I’ve been attending OR since the early 1990s, when it was still held in Reno, Nevada. (Persistent legend holds that the show was simply not invited back there one year when Reno officials belatedly realized that the attendees weren’t gambling or buying tickets to Englebert Humperdinck concerts.) Over the years, the show has had its minor ups and downs, but the 2009 and 2010 SLC post-Great-Recession ORs were scary in their dearth of both exhibitors and new products. Like the automotive industry after WWII, most companies simply recycled products with new colors rather than invest in development, while they waited to see in which direction the economy would go.

In 2012 the tide seemed to have turned. The Salt Palace Convention Center was packed with both exhibitors and attendees, the mood was buoyant, and I fully expected the 2013 show to be full speed ahead.

What I found was, to sum up a complex situation in one word . . . ennui. What can I say about a show in which one of the most interesting products I noticed was a tent stake?

The main hall of the center is where all the big guns in the outdoor equipment world hold court: Patagonia, Cascade Designs, Arc-teryx, The North Face, Marmot, etc. While there were a few highlights here (to be highlighted in a bit), the overall impression was of an industry either dangerously complacent or suffering from renewed pessimism. A worse prognosis came from a cynical friend in the community who dismissed the entire event with, “It used to be about people getting out and doing cool things. Now it’s about the lifestyle—people looking like they get out and do cool things.”

That might be too harsh, but not much I saw belied the viewpoint. For years the centerpiece of the south hall area was some form of climbing wall, open to anyone who cared to give it a try and always busy. Gone. Move north along the main aisle and you’d hit the big indoor pool where kayak manufacturers demonstrated their new models. Gone. Versions of both have been banished to the “Pavilions”—county-fair-sized tents north of the convention center, where new and/or underfunded companies hope to strike gold. The only “outdoor sport” in evidence in the main building was a slackline manufacturer’s demonstration area. Indoors and 12 inches off the floor, a slackline (basically a tightrope employing a strap rather than a rope) strikes me as something pinched from a county fair booth where you might win a stuffed animal if you can stay on it for ten feet (those who practice it over 2,000-foot chasms are, of course, in a different league). Yet, indeed, there seemed to be no shortage of clothing manufacturers—even Carhartt, traditionally a blue-collar supplier to construction workers and cowboys, was getting in on the craze, and touting their seniority to effete upstarts such as Mountain Khakis. Is this clothing/lifestyle thing really a trend, or did I employ motivated reasoning to reinforce unfair first impressions? Perhaps next year will tell.

Anyway, enough expostulating. Three days at OR were enough to ferret out a few products of note. Some were brand new and intriguing, some I had dismissed previously as unlikely to survive, but re-evaluated on their second or third appearance.

A traveling coffee pot one inch high . . .

A traveling coffee pot one inch high . . .

Coffee being uppermost in my mind each morning, I should start with the brew-in-bag product from Nature’s Coffee Kettle. It comprises a two-compartment foil pouch, in the top of which is a hermetically sealed packet of ground coffee of various flavors. You zip off the top, slowly pour in 32 ounces of boiling water, and the brewed coffee collects in the bottom section, from where it can be poured out through a screw cap. The sealed packet can be folded to take up a space no larger than six by eight inches by an inch thick. Although the product has been around a while, I never paid attention since the bag appeared to be a one-time-use-then-it’s-trash product. However, this time I stopped and spoke to the inventor, Matt Hustedt, who assured me the packet of grounds can be replaced, so the foil “kettle” could be used a half-dozen times or more.

I brought a couple samples home and tried the organic Columbian. After opening the top and eyeing the packet of coffee, I cut the amount of water I poured in to 24 ounces, and in addition, as Matt had suggested to enhance the boldness, upended the kettle several times to recycle the water through the grounds (be sure to rezip the top if you do this!). The verdict from this fan of strong, high-quality coffee, was . . . bravo. The flavor and strength were surprisingly good, although I’m glad I cut the water. I suspect the brew would have been even better if I’d poured in the water more slowly at the start.

While some (especially motorcyclists) might use the Nature’s Coffee Kettle as a primary travel brewing device; given its sealed nature (Matt claims to have brewed good coffee with two-year-old pouches) and nearly flat dimensions, I’m thinking one or two of them would be good backups to keep stashed somewhere in case you ran out of your Tanzanian Peaberry beans in the backcountry, or your hand-cranked burr grinder explodes and you can’t find a metate.

While on the subject of beverages, let’s move later in the day and talk about freeze-dried beer.

Backcountry soda and . . . beer?

Backcountry soda and . . . beer?

No, I’m not kidding, although “freeze-dried” is a deliberate misnomer. Like many of us, Patrick Tatera often wished for a way to enjoy good beer far in the backcountry, without the exertion of carrying it there. Rather than try to brew beer and then dehydrate it, he invented a method of brewing the “beer” parts of beer—i.e. the malt, hops, alcohol, etc.—into a concentrate. He then invented a bottle called a carbonator, which infuses that concentrate into the ice-cold mountain spring water you’ve collected 15 miles into your backpacking trip, and carbonates the lot. The result? Well, I’m not sure what the result is, as I haven’t yet tasted the finished product. But Patrick claims to be a devotee of high-quality beer, and none of the available brews claims to replicate PBR, so I plan to follow up and report. Pat’s Backcountry Beverages, as the company is known, also produces concentrates for soft drinks. I’ll try those too.

About that tent stake: It’s from UCO, a division of Industrial Revolution. It looks like an ordinary V-shaped aluminum tent stake, except for the cunning little LED light that slips over the top once you’ve pounded in the stake. Powered by a single AAA cell, it can be set to a 17-lumen constant glow, or a strobe. Besides obviating those headlong trips over tent stakes we’ve all accomplished, it will locate your tent for after-hours hikes. Neither the 10-hour burn time on constant nor the 24-hour life on strobe strike me as particularly efficient; I think they could halve the lumens and still effectively light the stake.

No more nighttime faceplants over tent stakes

No more nighttime faceplants over tent stakes

At the Industrial Revolution booth I also picked up some of their stormproof matches. These aren’t your ordinary stormproof matches: Strike one, and when its orange secondary material is burning fiercely, dunk it in a glass of water. Pull it out, give it a shake—and it will keep right on burning. Impressive. To go with them in my survival kit I added some Flame Sticks from Ace Camp. These green plastic sticks look like flashing from some molded product; you’d toss them in the trash if you didn’t know better. But once lit they’re reported to burn powerfully for five minutes, which is exactly what I got out of one in a light breeze. The sticks are too long to fit in the waterproof case the matches came in, so I clipped the ends off a half-dozen. There should be few circumstances in which I couldn’t get a fire going with this combination, except at the bottom of a pond.

If you can't light a fire with these, turn in your merit badge.

If you can't light a fire with these, turn in your merit badge.

Over the years I’ve tried several brands of cargo nets to secure those awkward loads in the cargo bay of Land Cruiser wagons, Wranglers, and Defenders, or on roof racks. I’ve hated all of them. It’s nothing to do with the products, really, it’s just that to wrap a variety of objects in a variety of vehicles, they wind up being huge, tangle-prone, and awkward, and more often than not snug nicely around half the contents while leaving the rest bouncing. But frequently ratchet straps just can’t encompass everything that should be secured. So I’m cautiously excited by the Lynxhooks interlocking tiedown system, a completely modular and infinitely expandable product comprising individual straps with adjustable buckles, a short length of natural rubber bungee, and a pair of hooks. The hooks are the clever part, as they can either connect to a tiedown point or snap to another hook—or five or ten other hooks—to create a custom-sized and custom-shaped spider of straps (or, of course, each strap can be used as . . . a strap). I got a sample, but plan to ask for more to create a net for the back of my FJ40. I’ll report in full then, but I don’t see how they wouldn’t work as advertised.

The Lynxhooks snap together to form custom cargo nets.

The Lynxhooks snap together to form custom cargo nets.

Finally, on to more advanced equipment. I walked past a booth in one of the pavilion tents and spotted a bunch of little square bricks perched here and there, each proclaiming “Text Anywhere.” I thought they were just cute displays, but it turns out they’re the actual device: Connected by wi-fi to any smart phone, they utilize the worldwide Iridium satellite system to allow two-way text messaging from pretty much anywhere on the planet. The device is $399, a subscription including 100 texts is $30 per month, you can idle the account for $5 per month, and it’s compatible with Apple, Microsoft, Android, Linux, or Blackberry operating systems. I wheedled the sales manager, Garry Harder, into sending one home with me then and there. I’ll review it soon, then we plan to take it to Kenya this fall where we’ll be working on another project with the Maasai and will be in the proper area for a real test. If it works as promised, it will be a huge step up from the typical one-way SPOT-type device.

TextAnywhere plus a smartphone = global texting.

TextAnywhere plus a smartphone = global texting.

More as I sift through 20 pounds of dealer catalogs, scribbled notes, and iPhone photos.

See our Flickr set Outdoor Retailer 2013 for more images of interesting products not covered here.

Nature's Coffee Kettle is here.

Pat's Backcountry Beverages is here.

Industrial Revolution is here.

Lynxhooks is here.

TextAnywhere is here.

Schuberth C3 helmet: 12 months and 10,000 miles review

by Carla King, CarlaKing.com

My last helmet squeezed my jawbone, giving me a headache after about an hour. The previous one pressed on my left temple. Another rattled, another fell forward over my eyebrows, and yet another let a constant stream of air up the back of my neck. Helmets have made me itchy and sweaty, the visors have popped off, and the air flow controls have never quite worked properly. I've worn half-helmets, full helmets, modular helmets, dual-sport helmets, other people’s helmets, cheap helmets, medium-priced helmets, and expensive helmets. But in Spring of 2012 I started wearing a Schuberth C3, and since then I have stopped to look at a view, to ask directions, to fill up my gas tank, to buy snacks at a convenience store, to make phone calls and to take photos, all with my helmet still strapped on.

WHY MODULAR?

WHY MODULAR?

I’ve always liked the idea of a modular helmet. I travel a lot and interact with people on the road, and it’s nice to be able to slide up the chin bar so people can see my face when I’m talking with them, especially when attempting a foreign language. But helmets have always been so uncomfortable that I've removed them every opportunity, sighing "aaahhhh" in relief from pressure-points, itching, and sweating. The Schuberth C3 is the first helmet I've owned that I don’t rip off my head as soon as the wheels stop turning, and that’s saying something, because I have been riding since I was a teenager.

Continue reading the full review here.

We will be running more motorcycle and equipment reviews from Carla, a longtime Overland Expo instructor and one of the most accomplished riders we know. Carla's been riding motorcycles since she was 14, and has ridden every kind of bike on most continents.

The amazing ClampTite

I know, I know—I’m starting to sound like Ron Popeil. But it’s been some time since I used a tool as cunning as this little device, which can do everything from replacing a broken hose clamp on a fuel line or seizing a rope end to repairing a stress-fractured luggage rack on a motorcycle or splinting a broken tie rod on a Land Rover.

But wait, there’s more! The ClampTite uses ordinary safety wire you can buy with the tool, or almost any on-hand substitute in a pinch, including fence wire and even coat hanger wire, to securely wrap just about anything that needs to be fastened or immobilized. And the size range it will handle is essentially limited only by the length of the wire.

You might think you could approximate what the ClampTite does with a pair of pliers and some twisting, but trust me, you wouldn’t be able to apply the amount of tension available through the tool’s threaded collar. Look at this sample of both a single and double wrap on a length of rigid PVC pipe. I tried and failed completely to get that much compression with an ordinary hose clamp.

The ClampTite can make either a single-wire or double-wire clamp (see above). With a single wire you can use as many wraps as necessary, although, depending on the material, friction will start to overcome the ability of the tool to adequately tighten the wire if you overdo it. On a radiator hose like I used for the test, a single wrap of doubled wire is more than stout enough; if you were repairing, say, a split axe handle you could use several wraps of a single wire, then repeat in several places along the split to completely secure it. The same procedure could secure a Hi-Lift jack handle along a broken tie rod, or . . . you name it. The potential applications are endless.

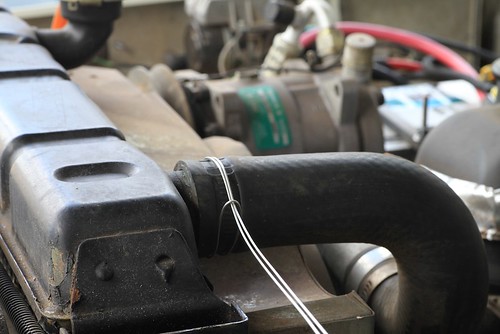

Begin a hose clamp by doubling a length of wire and wrapping it like so.

Begin a hose clamp by doubling a length of wire and wrapping it like so. Wrap it again and through the loop.

Wrap it again and through the loop.

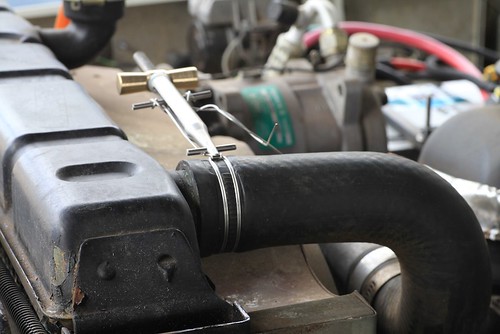

Attach the ClampTite, secure the ends of the wire, and screw in the bronze nut to tension the clamp.

Attach the ClampTite, secure the ends of the wire, and screw in the bronze nut to tension the clamp. Flip the tool to lock the wire.

Flip the tool to lock the wire. Release the tension on the tool, clip the wires, and . . .

Release the tension on the tool, clip the wires, and . . . . . . you're finished.

. . . you're finished.

I found the ClampTite easy to use. My biggest challenge was keeping the wire lined up correctly while installing a double-wrap clamp, to keep it from overlapping—although that probably wouldn't affect the seal on a radiator hose.

While it’s impressively compact (a larger model is also available), there will be places you simply can’t use the ClampTite. You need to be able to access the trouble spot to wrap it with wire, attach the tool at the spot, and have room to flip it (double wire) or twist it (single wire) 180 degrees to anchor the clamp once you’ve tightened it. But with ingenuity you can overcome many obstacles. Looking around our vehicles, I found a fuel line fitting on a carburetor that would be inaccessible if its hose clamp broke. However, by removing the fitting from the carburetor first and taking off the other end of the fuel line, one could clamp the line to the fitting, screw the fitting back in with the line attached, then re-attach the other end.

I think the ClampTite would be at least as useful on a motorcycle as in a four-wheeled vehicle, if not more so. I’ve seen many more parts fail on bikes due to the higher intrinsic vibrations and necessarily harsher ride. We had Tiffany Coates’s legendary BMW R80GS, Thelma, parked at our place for nearly a year some time ago. Thelma has seen long (200,000 miles), hard use and it shows. Thinking back, I’m sure I could have used up at least a hundred yards of safety wire reattaching various dangling bits on that bike.

ClampTite tools start at just $30 for a plated steel and aluminum model, which would be ideal for a motorcycle. The stainless and bronze unit I tested is $70.

Final note: Unlike the Ronco 25-piece Six Star knife set, ClampTite tools are made in the U.S. And you won’t get a free Pocket Fisherman with your purchase. Sorry.

ClampTite tools are here. Thanks to Duncan Barbour for the tip!

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.