Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

New from Bogert Manufacturing

I suspect Richard Bogert is one of those people who keeps a notepad and pen on the nightstand, so he can jot down inspirations that pop into his head at 3:00 a.m. I can’t see any other way he could come up with the volume of ideas he does—for the Bogert Aviation arm of his business, the military equipment, odds and ends such as high-quality bed frames, and the more recent foray into products suitable for overland travelers and four-wheel-drive vehicle owners in general.

I’ve written about Bogert’s Safe Jack system for the Hi-Lift jack (here), which transforms the Hi-Lift from a versatile but at times unstable lifting device into a rock-solid lifting device. Recently Richard shipped me a new suite of Safe Jack products that accomplishes similar wonders for the ubiquitous bottle jack.

Bottle jacks have several advantages over the Hi-Lift (or other beam-type jacks). They’re powerful for their compact size and weight, are physically much easier to operate given the hydraulic assist (with no danger of kick-back), and come in a wide range of lifting capacity. They’re significantly easier to use for tire-changing or inserting sand mats, since (sometimes with some excavating) one can place them under an axle and lift one wheel directly. To use a four-foot-long, 30-pound Hi-Lift in the same situation one must either lift the bumper—which requires lifting through the entire suspension travel as well before the wheel rises—or employ a Lift-Mate which attaches to the wheel, suitable for inserting sand mats but useless for tire-changing.

But bottle jacks have downsides too, and salient among them is the short lifting range—about six inches compared with thirty six for even the shortest Hi-Lift. Even double-extension bottle jacks (such as the excellent Italian-made Land Rover axle jacks, or the equally excellent German-made Power Team jack I own) top out at around a foot of lift. So if, for example, one needs to jack up a chassis member that sits 18 inches off the ground, and you’re using my eight-inch-tall double-extension bottle jack with a 12-inch lift, by the time the piston reaches the chassis you’ve got two inches of jacking function left. We all know what comes next: a makeshift platform of 2x4s, rocks, or worse to get the jack closer to the chassis. Screw extensions on the piston help but don’t solve the problem.

A universal base plate and axle cradle vastly enhance the stability of a standard bottle jack.

A universal base plate and axle cradle vastly enhance the stability of a standard bottle jack.

Richard solved it. The Bogert Bottle Jack Recovery Kit includes three extensions that slip securely over the typical 1 1/4-inch-diameter bottle-jack piston. One provides 2 1/2 inches of extension, another 5 1/2, and a third is adjustable from 8 to 12 inches. Stack them and you could theoretically lift against something 31 inches high with that eight-inch-tall jack still firmly on the ground. The kit also includes a plate to spread out the stress of the jack’s piston against a frame member or skid plate, and an axle cradle that hugely increases the stability of the jack under an axle tube. It all comes in a stout Husky zippered carrying bag big enough to also hold the (optional) bottle jack.

This plate disperses the stress of lifting on skid plates or a thin-gauge Land Rover chassis.

This plate disperses the stress of lifting on skid plates or a thin-gauge Land Rover chassis.

There’s more to the a la carte system. A universal base plate fits most bottle jacks up to 20 tons, and provides 48 square inches of surface area for stability and flotation in soft substrate—significantly greater than the 28 square inches of a Hi-Lift’s standard base plate. Not enough? The universal base plate with jack attached snaps instantly into Bogert’s twin-handled ”Big Foot” base plate, which covers a full 144 square inches of the earth’s surface, exactly the same as the common orange ORB Hi-Lift base plate (or Bogert’s own Safe Jack base plate for the Hi-Lift). If you’re lifting 3,000 pounds that would reduce the 200 pounds per square inch loading under a naked bottle jack to just over 20. The handles make it easy to scoot the jack into and out of spots under the vehicle.

With an extension and the cradle I was able to securely lift the back of the truck at the receiver hitch.

With an extension and the cradle I was able to securely lift the back of the truck at the receiver hitch.

The recovery kit enhances the versatility of any bottle jack, making it easier to use the jack to apply pressure wherever it might be needed—straightening a bent tie rod or bumper, fractionally raising an engine to replace a broken motor mount, or pushing on a roof rack to ease a vehicle away from a rock it has slid into sideways.

One complaint—more of a suggestion really: Bogert Manufacturing’s red-white-and-blue “Always made in America” stickers are plastered on each and every piece in the Safe Jack system—fine, except that one is also plastered on the made-in-China bottle jack if you order that option. I’d urge Richard to either leave the tag off the jack, or (better) find an American-made bottle jack. That nitpick aside, this is another imaginative and useful product from Richard Bogert’s bedside notepad. Bogert Manufacturing is here.

(Edit: Richard says the stickers are no longer applied to the jack. Do U.S.-made bottle jacks even exist any more?)

Pronghorn makes the leap

To say I "consulted" on the Pronghorn Overland Gear Modular Front End System (MFES) for the Jeep Wrangler JK would be a bit of an overstatement. What actually transpired was, they brought a prototype bumper to our place and mounted it on a Wrangler, we took it out in the desert, and I used the Warn 8274 winch on my Land Cruiser to try various ways to rip it off that Wrangler, or even bend it a little. I failed. I suggested a tweak to the fairlead mount and a few other details, but essentially the Pronghorn MFES-JK was ready to go out of the box.

At the 2013 Overland Expo, Pronghorn made quite a splash, not just because of the astounding strength to weight ratio of the bumper system, or the innovative details such as their Rotator Shackle or GearMount system, but because of the completely modular nature of the product, which allows a user to choose anything from an unadorned short bumper suitable for the fiercest cross-axle slickrock obstacles, to a full-width unit with brush guard ideal for fending off third-world goats and taxi drivers. In fact if you so choose you can swap back and forth between the configurations.

This week the company launched its website (go here), and is in full production with the MFES-JK. They're also working on a prototype system for the Toyota Tacoma, which we will be delighted to try out on the JATAC. Other models will follow, as will rear bumper systems, skid plates, and several not-directly-bumper-related-but-fascinating bits of four-wheel-drive kit on which the founder of the company, Trey Herman, and I are trading emails and ideas. Stay tuned, but in the meantime if you own a Wrangler and are in need of the best bumper available for it, take a look. (Full disclosure: I was impressed enough that Roseann and I now own a small stake in Pronghorn Overland Gear L.L.C.)

Irreducible perfection: Vulture Safety Loops

Last year, during a crossing one of Egypt’s great sand seas, I wanted to get some video footage of the Land Cruisers from a camera mounted on the hood and, if possible, the side of the truck. I had a massive Manfrotto suction clamp to secure our Canon 5D MkII, but there was no way I was going to trust $3,500 worth of camera and L lens to a glorified bathroom plunger. So I rigged up a pair of safety lines to the camera’s strap with some 550 paracord, secured with my best bowlines to the roof rack and the base of the windshield wipers.

As it happened, the suction mount performed flawlessly, even on its side with gravity working against it over some firm sand corrugations (sorry about the bathroom plunger remark, Manfrotto). But the camera strap flapped around while the vehicle was in motion, and the paracord lines seemed a bit jury-rigged. I was happy to have them, but mused about fabricating something that would be more readily accessible and a little more elegant as well.

Fast forward to this summer’s Outdoor Retailer show, where Roseann and I had coffee with William Egbert of Vulture Equipment Works. VEW is best known for making the strongest camera straps in the world, designed for rigging systems when the photographer is, say, hanging out of a helicopter door (review to come). But I was intrigued when William produced a couple of lengths of cord no thicker than dress shoelaces, with a loop at each end. And he really got my attention when he said, “You could hang a motorcycle from one of these.” I raised an eyebrow, and he added, “Seven hundred pound load limit.”

The Vulture Safety Loops, William told us, are made from “a proprietary weave of aerospace fibers.” Hmm . . . After being subjected to a short waterboarding session, he admitted the actual material was a para-aramid (Kevlar is the brand name of one such fiber). Kevlar is produced from the reaction of para-phenylenediamine and molten terephthaloyl chloride—and despite having been discovered in the 1960s, chemists are still not certain exactly why it displays such an astounding strength-to-weight ratio. It’s expensive stuff, in part because, I’m told by someone who knows these things, “Manufacturing the para-phenylenediamine component is difficult due to the diazotization and coupling of aniline.” So now you know why too.

Safety Loop (bottom) compared to 550 paracord

Safety Loop (bottom) compared to 550 paracord

The VEW Safety Loops come two to a package; one 24 inches long and one 38. A woven sheath protects the fiber within from abrasion, but they’re still so slender it’s hard to believe the strength. I didn’t hang any of our motorcycles from one, but I did hang myself from one, and it laughed off my 150 pounds. They display virtually zero stretch, and the material is extremely cut- and flame-resistant.

I can foresee a bunch of uses for these elegant but brutish cords. They’d be perfect as insurance on duffels or Pelican cases strapped to a roof rack, or gear bungeed on the back of a motorcycle. For photography they’d clearly be an excellent replacement for my paracord bodge jobs, or one could use them to secure a tripod in windy conditions, or to keep a camera on a strap from flopping. Beyond that? You could probably employ one in a motorcycle recovery operation.

At $29 a pair they might not seem cheap at first, until you consider both the strength-to-weight ratio and the strength-to-cost ratio. One of them weighs three grams—that’s undoubtedly the lightest insurance you can buy for $3,500 worth of camera and L lens . . .

Vulture Equipment Works will be at Overland Expo 2014. In the meantime you can find them HERE.

Followup - Because I just thought of what might be the best use of all for the Vulture Equipment Works Safety Loops: Anti-theft leashes.

We're about to spend several layovers in airports in Brussels, Geneva, and Nairobi. Connecting my Filson briefcase, or the new Pelican 1510 rolling carryon I'm testing for camera transport, to a chair or table leg with one of these would severely hamper a snatch-and-run thief.

A proper knife

The knife was almost certainly mankind’s first manufactured tool into which we put not just craftsmanship, but artistry. First (after poking around that funny black monolith) we simply grabbed handy tree limbs for clubs, or rocks suitable for smashing things. Then, about 2.5 million years ago, a perceptive hominid noticed a river rock with a naturally chipped edge that proved much superior for cracking open bones or the skull of a rival. Jump ahead a million years, and his Homo erectus descendants had learned how to flake quartzite and basalt into sophisticated and sharp bifaced hand axes. Next came flint and obsidian spear points and arrowheads, with finer and finer workmanship. Somewhere along the line a smart craftsman lashed a bone or antler handle to his skinning blade—and from that point forward the design of the knife strayed not a bit except for the steady evolution of material and the eventual innovation of folding blades. The knife became our single most indispensable personal-carry tool, and stayed that way right up to the advent of the iPhone.

When I was younger, if you went outdoors, whether for hiking, backpacking, canoeing, car camping, hunting—whatever—you carried a fixed-blade sheath knife, the direct descendant of that flint-and-bone progenitor. It was axiomatic that the knife would be your primary tool for dozens of tasks: cutting rope and webbing, field-dressing fish or game, cooking and eating, carving, you name it. It was also axiomatic that a fixed-blade knife would be the best choice for those tasks, given its superior strength and control over a folding knife, and easy one-hand accessibility right there at your belt. I got my first sheath knife when I was seven, as did my best friend, and neither we nor neighbors who saw us carrying them around our rural community thought a thing of it.

Not any more. With the exception of increasingly rarified circumstances and company, wearing a sheath knife today—even if you’re an adult—seems to be considered, at best, ostentatious, and at worst an aggressive “statement” that indicates you might also support private ownership of tactical nuclear weapons. I’ve related before the story of an acquaintance who wore one into a West Coast coffee shop and was accosted by a woman demanding to know what he was doing “with that weapon in here.” He swears he replied, “Lady, you should hear what the voices in my head are telling me to do with it.” A seven-year-old carrying a sheath knife today? He would probably be remanded to Social Services and his parents jailed.

I say we fight back—figuratively speaking, of course. If you own a fixed-blade knife and have ever felt too self-conscious to carry it, and then had to perform some task with a pocket knife clearly too small for the job, strap that thing on next time. Don’t own a fixed-blade knife? Go get one, learn how to sharpen it properly, and carry it proudly.

There are undoubtedly thousands of fixed-blade knife (let’s say FBK from now on) models marketed as suitable for general field work, but you can broadly divide their design philosophy in two: handy designs with plain (i.e. non-serrated) edges and blades between three and five inches in length, and much larger, heavier tools with six, eight, even ten-inch blades (often nearly 1/4-inch thick at the spine), that supposedly can also be used for chopping, hammering, and, if you believe some of the ads, hacking your way out of your downed F16’s cockpit, spearing caribou after securing the handle to a stick with your unraveled paracord bracelet—and, of course, fighting off zombie hordes.

Gee, I guess my prejudice is showing already.

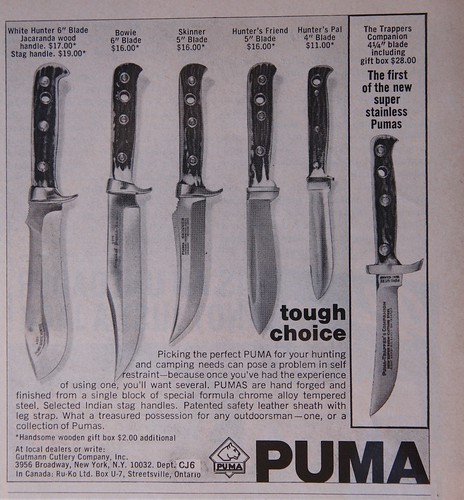

For decades, my FBKs were all the former style, from that first blade in second grade to the Buck Personal that was the first knife I bought myself, to the dream knife I couldn’t afford then but purchased at a usurious collector price decades later: the near-mythical (well, among knife wonks anyway) Puma Trapper’s Companion—$32 in 1970; $400 30 years on.

A classic Puma Hunter's Friend, above, and the even more classic Trapper's Companion, below. (Sadly, Puma knives aren't what they used to be; those made prior to 1995 or so are the best) Along the way I discovered perhaps the most versatile style of all: the so-called bushcraft knife, defined by the Woodlore, which was designed by Ray Mears in 1990 and is now copied by knifemakers everywhere. Like Ray himself, the Woodlore is an unassuming thing with a 4.25-inch, spear-point blade. It employs what’s known as a Scandinavian (“Scandi”) grind: The blade holds its thickness from the top (spine) most of the way toward the edge, which has a single bevel extending quite high up each side.

A classic Puma Hunter's Friend, above, and the even more classic Trapper's Companion, below. (Sadly, Puma knives aren't what they used to be; those made prior to 1995 or so are the best) Along the way I discovered perhaps the most versatile style of all: the so-called bushcraft knife, defined by the Woodlore, which was designed by Ray Mears in 1990 and is now copied by knifemakers everywhere. Like Ray himself, the Woodlore is an unassuming thing with a 4.25-inch, spear-point blade. It employs what’s known as a Scandinavian (“Scandi”) grind: The blade holds its thickness from the top (spine) most of the way toward the edge, which has a single bevel extending quite high up each side.

Knife edge grinds. Courtesy Off the Map custom knives.

Knife edge grinds. Courtesy Off the Map custom knives.

The Scandi grind is immensely robust—bushcrafters use these knives to split two-inch-thick limbs lengthwise by “batoning,” that is, holding the edge of the blade against the end of the limb, and using another length of limb to hammer the knife straight down. The technique even works across the grain. Yet the Scandi grind can be given a razor edge; that broad bevel makes it easy to index the blade on a simple sharpening stone if you don’t have a sophisticated system such as the Edge Pro. If the grind has a weakness, it is for exceptionally fine slicing—that broad bevel acts as a wedge rather than a scalpel. Scandi blades make lousy cheese cutters.

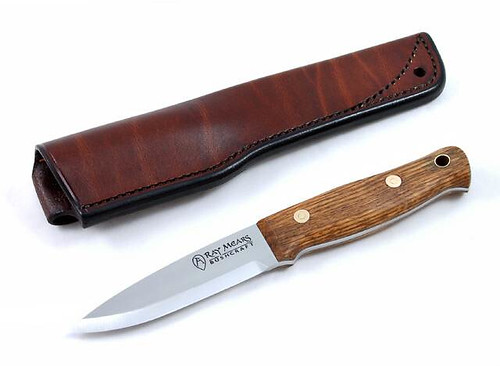

The current Ray Mears knife has a durable English oak handle.

The current Ray Mears knife has a durable English oak handle.

The genuine Woodlore knife rightfully carries a substantial premium given its provenance; high-quality copies are available for less for those who don’t need or can’t afford the Woodlore signature. I have a bushcraft knife nearly as well-known in the community: a stout design called a Skookum Bush Tool, made in Whitefish, Montana by Rod Garcia. Rod enhanced the Woodlore pattern by adding a flat steel back on the handle, which is welded to the full-tang blade and enables the user to hammer this thing point-first into, well, anything that needs a knife hammered into it.

Many other knives parallel the bushcraft style, from the astoundingly underpriced ($18) and overperforming Mora Clipper to custom models made with exotic steels and even more exotic hardwood scales (handles), which can easily top $500. As an all-around field knife the bushcraft design is hard to beat, although flat-ground and hollow-ground blades also work very well for most tasks, and better for some.

Top to bottom: Mora Clipper, Helle Eggen, Wood Bear, Skookum Bush Tool, Helle Temagami.

Top to bottom: Mora Clipper, Helle Eggen, Wood Bear, Skookum Bush Tool, Helle Temagami.

In the last few years an entirely different style of FBK has become increasingly popular, especially among the survival community (by which I mean people interested in survival skills, not the guys who hole up in the Idaho mountains with “Bo Gritz for President” posters tacked up in the fallout shelter). The style is frequently referred to even among its proponents as a “sharpened pry bar.” Forget handiness—these knives are massive, and built to withstand laughable abuse—one popular demonstration involves chopping through a concrete block, another, repeatedly stabbing though a car door. The fact that they have a cutting edge seems secondary to the astounding breadth of ancillary destructive purposes to which one is assured they can be directed. The names of these things echo their marketing: Compare the quasi-Elvish “Woodlore” with the “Swamp Rat,” the “Black Legion,” or the “Extreme Survival Bowie.” And, yes, there is an official “Zombie Killer,” with a, not making this up, “Toxic Green” handle.

I picked up one of the early examples of this genre, the Gerber LMF-2, at a trade show some years ago, and immediately put it down. The knife was heavy and unbalanced, and its “tactical” sheath, complete with de rigueur mid-thigh mounting straps, weighed more than the knife. Similar models from other makers impressed me no more, and I dismissed the entire concept as a short-lived fad.

Wrong. The LMF-2 is still around, and has been challenged by even more bloated competitors. So I decided to give the concept a fair chance, and procured an LMF-2 as well as a Ka-Bar/Becker BK-2. I used each for several days around our place and in the surrounding desert, on tasks for which I’ve been using much smaller knives for tens of years.

Top: the Becker/Ka-Bar BK-2; bottom, the Gerber LMF-2.

Top: the Becker/Ka-Bar BK-2; bottom, the Gerber LMF-2.

And . . . I still don’t get it.

The LMF-2 has that most worthless of blade styles, half plain and half serrated—which leaves neither enough room to do its job. The (reasonably sharp) plain edge is out at the end, is mostly curved, and is barely three inches long despite this knife’s 10.5-inch overall length and three-quarter-pound weight (LMF, perversely, stands for “Lightweight Multi-Function”). The blade on my Swiss Army knife is only a half-inch shorter. The Gerber’s serrated section, as with all such edges, is virtually impossibly to sharpen in the field—although the nifty sharpening slot in the LMF-2’s plastic sheath is okay for touching up the plain edge. By way of comparison, one of the best field knives I own, a Helle Temagami, weighs just 5.4 ounces despite 4.5 inches of usable blade.

The knife is undeniably stout. The pointed pommel, I’m sure, could “egress through the plexiglass of a chopper” as Gerber claims, or be employed for an occiput strike on a sentry—which all of us are sure to need to do at some point in our lives. In fact, as kit for a combat pilot, the LMF-2 might not be a bad tool at all. But for any kind of regular use in the field—including survival—the LMF-2 has all the wrong answers to the questions that are most asked in such situations. It even touts the ultimate lunacy for a survival knife: three holes in the handle so you can “lash it to a stick and make a spear.” Lord spare us from such nonsense.

However. If I thought the Gerber was unwieldy, the Ka-Bar/Becker BK-2 makes it look like a surgeon’s scalpel from Porsche Design.

I’m convinced the designer of the Becker had an LMF-2 for comparison, and simply decided that whatever it had, the BK-2 was going to have more. So the Gerber weighs 12 ounces? This knife is going to weigh a pound. The Gerber’s blade is a fifth of an inch thick? Ha!—we’ll make ours a quarter of an inch thick. And then add a bit.

The result is one of the most cartoonishly overbuilt and comically awkward knives I’ve ever owned.

Seriously? The monstrous BK-2 next to the far more practical Temagami.

Seriously? The monstrous BK-2 next to the far more practical Temagami.

The makers tout the Becker’s chopping ability—the supposed payoff for the weight and bulk—but in fact it’s a lousy chopper. Despite the massive blade, it’s still handle-heavy, and the edge is not long enough to gain the speed and momentum even a lightweight machete can achieve. There is no reason—not one—to make a knife blade a quarter of an inch thick, except to one-up someone else’s blade. No user could ever put enough leverage on this knife to bend, much less break it. It is simply dead weight. Its sole positive feature is that it blessedly dispenses with serrations (or, worse, saw teeth), but the spine is so thick and the knife so heavy that normal cutting operations—the kind you need to do 99 percent of the time even if you are a combat pilot—become ham-fisted struggles, like tapping in finish nails with a three-pound sledge.

The Becker dwarfs a lovely model from knifemaker Lynn Dawson, with a hollow-ground blade just three inches long. Yet I field-dressed a whitetail deer with the Lynn knife . . .

The Becker dwarfs a lovely model from knifemaker Lynn Dawson, with a hollow-ground blade just three inches long. Yet I field-dressed a whitetail deer with the Lynn knife . . .

. . . and the Lynn sports some nice file work on the spine. Tough doesn't have to be ugly.

. . . and the Lynn sports some nice file work on the spine. Tough doesn't have to be ugly.

Believe it or not, the LMF-2 and BK-2, with mere five-inch blades, are on the small end of their phylum. The ESEE Junglas (pronounced hoonglas) sports a 9.75-inch blade—actually almost long enough to be credible as a chopping tool, but with a concurrent reduction in practicality to near zero for any normal cutting tasks (To be fair, ESEE makes some entirely practical smaller models as well).

Let’s put together some numbers here. For the weight of a BK-2 one could carry a Helle Temagami, or a Woodlore clone, or any number of other fine, compact, well-balanced—and, dare I say, beautiful—cutting instruments, plus a Gerber folding saw, plus a lightweight sharpener. You’d have a vastly superior knife and a better, safer way to cut through larger limbs than hacking away with that “sharpened prybar.”

Ah, but what about the scenario the armchair experts like to debate ad nauseum: You’ve somehow been stupid enough to be caught out in the wilderness with nothing but a single knife. No saw, no machete, no matches, no tent, no iPhone. You need to survive with that one tool.

Give me the bushcraft knife any day.

Most of the tasks you’ll need to do to stay alive in such situations—building a shelter, making fire, perhaps constructing snares or deadfalls—are far more easily accomplished with a modestly sized blade. You won’t need branches larger than two inches in diameter for a lean-to, and those are easily cut with a bushcraft knife and, if needed, a baton. (Batoning is also infinitely safer than chopping; need I mention that severing a major artery would be inconvenient at this point?)

The rest—hearths and drills for a friction fire, snares, field-dressing game—require a deft touch with a blade. You’ll operate more quickly, surely, and with less energy expenditure if you have a knife as deft as the task.

And back in the real world? No contest. I got annoyed just carrying the BK-2, much less using it. It was a major relief to get back to my normal knives.

If you’re traveling by 4WD vehicle, or even by motorcycle where weight is much more of a concern, there’s simply no reason to consider dragging along an awkward, heavy knife that tries to take the place of two or three tools, even if the concept worked. Buy a good, sensibly sized FBK, and carry a folding saw, hatchet, or small axe for larger cutting tasks (for a really nice combination look HERE). You’ll be more effective and safer.

Besides, I hear axes work better on zombies anyway.

Edit: Found an old ad. The Trapper's Companion originally listed for $28, not $32. I should have got a second job and bought 20 of them then.

Edit: Found an old ad. The Trapper's Companion originally listed for $28, not $32. I should have got a second job and bought 20 of them then.

Another edit: Found this on a scouting site in an article about knives. I'm speechless:

I am a scout leader (aka Scout master) with Scouts Australia. Here in Western Australia this is a copy of our Policy and Rule regarding knives

K1. KNIVES. K1.1 Statement.

The Scout Association of Australia, Western Australian Branch (“the Association”) strongly recommends that all members be aware of, and exercise all possible care in, the use of knives.

K1.2 A sheath knife should not be worn by any member on, or participating in, Scouting activities.

K1.2.1 The wearing of a sheath knife is considered being contrary to State Law, particularly where the knife is displayed in a public place such as a street or a point of gathering.

K1.3 The use of a good quality pocket knife is strongly recommended and the use of such is encouraged under circumstances by all members on, or participating in, Scouting activities.

I'm going to go strap on every sheath knife I own and find a coffee shop . . .

Links:

Woodlore, Helle, Mora, Wood Bear, Skookum Bush Tool, Off the Map, Ka-Bar, Gerber

For interesting Puma lore, and occasional knives for sale, go HERE.

A follow-up: Patrick York Ma of Motus and I apparently had a bit of a mind meld a few weeks ago. Read his piece on knives here.

Tire pressure

The load index 109, on the right, is used with the load range to calculate optimum pressure.

The load index 109, on the right, is used with the load range to calculate optimum pressure.

A reader, Christian, sent in this comment to my recent post The physics of tires and lifts:

I have a related question that might warrant its own post. Is there a formula for finding your optimum tire pressure? Sounds simple enough. Most “experts” just say to check the owner’s manual. I’m skeptical because my new F150 has a front/rear weight ratio of 60/40, yet Ford recommends a higher pressure in the rear (60 rear, 55 front). I'm assuming this is in anticipation of a full payload but it seems to me that the correct pressures should be based on actual axle loads and tire volumes (i.e. a larger, wider tire will need lower pressures but the front/rear ratio should remain the same). Off-road pressures will be much lower (and highly variable) but again should utilize the same front/rear ratio. Does this sound right?

Christian, common sense is leading you in the right direction.

Tire pressures recommended by vehicle (and tire) manufacturers have varied significantly over time, often depending more on what they perceived as their customers’ priorities than on efficiency or even safety. In the days of Ford Galaxies and Buick Rivieras (and 32 cents-per-gallon gas), it was all about ride comfort, and recommended tire pressures hovered in the 20s. Today, fuel efficiency is the name of the game, and pressures are much higher, as you found on your F150. However, as you noted, the manufacturer invariably lists only a single figure. Especially in the case of a pickup, loads are likely to vary tremendously. Proper pressure for a light load will be inadequate for a heavy load, and proper pressure for a heavy load will be excessive for a light load and will cause premature tread wear in addition to a bouncy ride.

There are a couple of good ways to determine proper tire pressures for your vehicle to compensate for varying loads. First is an inflation/load chart. Why these aren’t front and center on all tire company websites I have no idea—most specification charts list only maximum load—but if you search deeply enough you can find them. We’ve posted one used by Discount Tire HERE.

An inflation/load chart uses the load index listed on the tire’s sidewall (after the sizing information), and the load range (C, D, E, etc.) to determine an optimum pressure. Much better than a single figure, obviously. To exploit this information fully, however, you need to know how much weight is on each tire. You can calculate that closely by finding a commercial scale the weighing each end of your vehicle, then dividing each by two. If you have a slide-in camper you remove for commuting in between trips, you can either make two trips to the scale or calculate the added mass of the camper if you know its dry weight. With that information in hand, you can cross-reference the chart to arrive at a very useful figure.

A simpler way to determine optimum tire pressure (as well as to double-check the chart method) is by “chalking.” Use a piece of bright chalk to mark a thick line directly across the tread of each tire. Drive a few hundred yards on pavement (preferably in a straight line) and look at the line. If it is wearing off evenly, your tires are correctly inflated, as the tread is bearing the load uniformly across its width. If the center of the line wears off more quickly the tire is overinflated, and if the edges wear off first it is underinflated. You might have to use paint rather than chalk to ensure the line doesn’t wear off too quickly.

Both these methods are designed to calculate road pressures. Once you have them figured, you can use them to arrive at starting points for airing down on off-pavement routes. A 30 to 40-percent reduction in pressure is usually enough to lengthen the tire’s footprint effectively, increasing traction and reducing impact on the trail as well as attenuating bounce over washboard and rocks. For deep sand one would drop quite a bit more than that, of course.

This might seem like more trouble than it’s worth to some. But you only need to do the weighing once per vehicle, and then recalculate if you buy different tires. But maintaining ideal tire pressures—as opposed even to just adequate—will significantly increase tread life, in addition to enhancing every aspect of tire performance.

The physics of tires and lifts

The JATAC with Four Wheel Camper mounted; LT235/85 R16 BFG All-Terrain tires, Boss air bags on stock rear springs, Icon shocks at all four corners.

The JATAC with Four Wheel Camper mounted; LT235/85 R16 BFG All-Terrain tires, Boss air bags on stock rear springs, Icon shocks at all four corners.

At the Overland Expo this May, Roseann gave a walkaround of the JATAC to a crowd of about 40 attendees, and throughout the weekend we were frequently approached by individuals and couples who’d seen it displayed or had read about it here, and who had various questions. Most were of the general general how-do-you-like-the-combination sort; many got into specifics of our modifications. But two questions about what we hadn’t done cropped up with interesting frequency:

- “Why didn’t you install a suspension lift?”

- “Why didn’t you install larger tires?”

The short answer to both questions is, “Physics.” The long answer follows.

Our goal in mating a Toyota Tacoma with a Four Wheel Camper was to strike a balance between reliability, durability, capability, comfort, and convenience. The camper provides comfort and convenience; it’s up to the truck to contribute reliability, durability, and capability. Part of the balance is realizing that roughly 1,000 pounds of comfort and convenience has potentially significant effects on the other three.

Reliability of the Tacoma should be a given. The Identifix rating for the current generation Tacoma shows five stars for every year since 2006. Our 2000 Tacoma was the single most reliable vehicle I have ever owned: In 160,000 miles we did nothing to it except scheduled maintenance. Not one repair. Even my faithful 1973 FJ40 couldn’t match that record at that mileage (burned exhaust valve at 150,000). It’s still too early to pass judgement on the new truck, but statistically we should be able to look forward to a similar experience.

Durability should be a given as well, certainly in terms of the drivetrain. Engines in general are lasting longer these days (200,000 miles really is the new 100,000), thanks to better materials and more precise machining capabilities—and Toyota engines, transmissions, and differentials stand out even among these higher standards. I’m still not completely sold on the composite bed or the open-channel back half of the chassis, but my master Toyota mechanic friend Bill Lee keeps telling me to stop fretting.

That leaves capability, which is what most people are attempting to augment with suspension lifts and larger tires (unless they’re strictly after the looks).

The Tacoma as we got it, with stock P245/75R16 all-season tires (30.5" diameter). It’s true that a mild suspension lift will increase chassis ground clearance and—if properly specced for the vehicle—improve suspension travel and compliance, enhancing both ride comfort and the ability of the truck to keep all four wheels on the ground for better traction when traversing rough terrain. Larger-diameter tires also increase ground clearance, and provide a fractionally longer footprint that can enhance traction.

The Tacoma as we got it, with stock P245/75R16 all-season tires (30.5" diameter). It’s true that a mild suspension lift will increase chassis ground clearance and—if properly specced for the vehicle—improve suspension travel and compliance, enhancing both ride comfort and the ability of the truck to keep all four wheels on the ground for better traction when traversing rough terrain. Larger-diameter tires also increase ground clearance, and provide a fractionally longer footprint that can enhance traction.

But there is a price to be paid for those gains. Let’s look at tires first.

A larger tire weighs more than a smaller tire—common sense, obviously, but the range of effects of that weight are not all obvious. As an example, let’s compare a couple of BFG All-Terrains. The LT235/85 R16 ATs we recently installed on the Tacoma are 31.7 inches in diameter, and weigh 46.4 pounds each. If we decided to go up in diameter a very modest 1.5 inches, to a 295/75 R16 AT at 33.2 inches diameter, that tire weighs 57 pounds. That’s ten pounds of unsprung weight (a term that refers to weight not supported by the suspension, including wheels and tires, brake components, bearings, axles, etc.—think of everything that goes up and down under the vehicle when you hit a bump) to gain 3/4-inch of ground clearance. Adding ten pounds to a vehicle’s unsprung weight has a far more dramatic effect on ride and handling than adding the same amount to the sprung mass. The springs and shock absorbers have to react to that weight over every imperfection in the road.

But that’s not the only effect. The mass of a larger tire (and, if fitted, a wider wheel) places additional stress on the braking system and retards acceleration—and the tire’s rotational moment of inertia, which increases with the square of diameter if I’m remembering my physics correctly, affects both as well. A 2003 study of the effects of suspension lifts and larger tires showed that going from a 32-inch tire to a 35-inch tire resulted in a ten percent loss in brake efficiency. That’s a significant effect on your ability to stop quickly.

Finally, a larger-diameter tire affects gearing. For example, at a constant 65 mph, the engine in a vehicle equipped with 4.11 differentials, a 1:1 top gear in the transmission, and 31-inch tires will be turning approximately 2900 rpm. With 33-inch tires the same vehicle will be turning 2720 rpm. That might sound like a good thing—after all, lower engine speeds should equate to better fuel economy, right? Unfortunately, it’s rarely so. You’re messing with a torque curve that the factory knows inside and out, and you can bet they’ve calculated the final drive ratio to optimize that curve. The losses associated with the extra mass and rotational inertia will almost certainly cancel out any possible gains in highway mileage with increased city consumption, as shown by numerous controlled studies.

Going up in tire diameter will also hurt your low-range performance, since the vehicle will be traveling faster at any given engine speed. That will reduce your control in low-speed situations. Few vehicles these days come with low-range transfer-case gears I consider low enough anyway (although the now nearly ubiquitous automatic transmission helps), so compromising what’s there makes little sense.

Why not simply regear the differentials to compensate, as dedicated rock crawlers do when they install those big 40-inch-plus tires? In terms of correcting the overall final drive ratio, it works—but at the expense of differential strength. The problem lies in the pinion gear, the only gear of the two major pieces in the differential one can change in size to alter the gearing (the ring gear is limited by the size of the differential case itself). So when one goes from, say, a 4:1 differential to, say, a 5:1, the pinion gear is essentially reduced in size from one fourth the size of the ring gear to one fifth its size. Additionally, the smaller pinion gear means that fewer teeth will be in contact between the two gears at any one time. And you still face the inescapable physics of accelerating and decelerating a larger, heavier tire. Breaking a diff on a local rock-crawling trail would be a pain. Breaking a diff on the Dempster Highway—or on the Dhakla Escarpment—would be a major pain.

What about suspension lifts? Done correctly (i.e., with properly rated springs and shocks; no eight-inch shackles or lift blocks), and kept within reasonable limits (two to four inches on most vehicles, especially those with independent front suspension), the biggest disadvantage you’re likely to encounter is increased drag and reduced fuel economy. True, your center of gravity will be fractionally higher, but the increased ground clearance for approach, breakover, and departure angles is probably a fair tradeoff. However, on a truck with a cabover camper, overhead clearance becomes an issue. On some of the biological surveys we do in Mexico, trees hang low enough over the approach trails to be a concern even with a stock suspension.

All this might sound like I’m dead set against straying at all from factory suspension heights and tire sizes. Not at all—but doing so does involve compromise, and the further one strays from stock tire sizes and suspension heights, the more compromises involved. As long as you’re aware of the issues, consider the cost/benefit ratio, and don’t go all monster truck, your approach might well be different than ours yet still effective for you. Consider my FJ40, which has both a mild (two-inch) Old Man Emu suspension lift and tires (255/85R16 BFG Mud-Terrains) that are at 33 inches significantly larger than the teeny factory-supplied 29-inch tall Dunlops. I settled on the combination after years of driving the vehicle stock, and with careful consideration of the drivetrain. The FJ40’s rear axle shafts are the same diameter as those in a Dana 60 (which is installed on 3/4-ton pickups), and its ring and pinion gear are nearly as stout—I’m on my original differentials at 320,000 miles. The front Birfield joints are not as bulletproof, but very few FJ40 owners have problems with them unless they’re running 35-inch or taller tires with power steering (my steering is powered by how hard I can turn the wheel). Mechanic-friend Bill once said that if I ever broke a Birfield with my setup he’d drive out and replace it for free. He hasn’t yet had to pay up on that offer. Also, significantly, the 1973 FJ40 came from the factory with drum brakes on all four wheels. I’ve installed discs all around, so my braking system is far superior to the factory setup even with the larger tires.

With a two-inch OME suspension, 255/85/16 tires are a good fit on the FJ40. Rear tires tuck into fender well without rubbing when springs are fully compressed.

With a two-inch OME suspension, 255/85/16 tires are a good fit on the FJ40. Rear tires tuck into fender well without rubbing when springs are fully compressed.

Given our intended use of the JATAC, which will combine long trips on pavement, extended mileage on dirt roads (we drive seven miles of dirt road just to get home), frequent use on four-wheel-drive trails, but little or no intensive rock crawling/mud surfing unless we find ourselves in a situation that requires it, we elected to stay with a very moderate size increase on the tires (to those 235/85/16 BFG All-Terrains), and stock suspension height. I leveled the back end of the truck with a set of excellent Boss air bags over the stock springs, and the shocks at all four corners are adjustable Icons with remote reservoirs.

Boss air bags augment the Tacoma's stock springs to maintain a level stance with varying loads.

Boss air bags augment the Tacoma's stock springs to maintain a level stance with varying loads.

We still plan to augment the JATAC’s off-pavement capabilities in other ways. First, we’ll be adding a locker for the rear differential—after tires (maybe even before) the absolute best way to enhance traction in difficult situations. Second, we’re working with Pronghorn Overland Gear on a prototype aluminum winch bumper. Pronghorn has just introduced an extremely high-quality modular bumper system for the Jeep Wrangler; the Tacoma is next on their list, and if the result is as good as the Wrangler version it will be good indeed—improbably light yet strong enough to take the the most demanding stresses of winching without complaint*. The Pronghorn bumper will also be compatible with the Hi-Lift jack already mounted to the Four Wheel Camper (see here). With a winch mounted up front we’ll have a backup plan if our tires and locker (and piloting) can’t get us out of a sticky situation. Finally, Pronghorn will also be developing a full aluminum skid-plate system for the Tacoma, so if our moderate ground clearance proves inadequate now and then, the underside of the truck will be fully protected.

As with many trucks employing independent front suspension, the lowest spot on the JATAC's undercarriage is the rear differential, visible here beneath the front factory "skid plate." The diff's placement in the center of the axle means it's more likely to drag on high-crowned trails. Larger-diameter tires would increase this clearance fractionally; a suspension lift would not.

As with many trucks employing independent front suspension, the lowest spot on the JATAC's undercarriage is the rear differential, visible here beneath the front factory "skid plate." The diff's placement in the center of the axle means it's more likely to drag on high-crowned trails. Larger-diameter tires would increase this clearance fractionally; a suspension lift would not.

This reminds me: I keep meaning to add a set of MaxTrax as well. We were recently on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim after a heavy rain, and the washes in the House Rock Valley had flowed energetically. The first one we came to had subsided to a trickle, but the substrate was still treacherous. The odds were nearly certain we could have crossed with no trouble, but we were a single vehicle with no winch. A stuck truck could have meant hours of digging out, with more rain and flash floods likely. Additionally, beyond this first wash were several larger ones between us and our goal on the rim. So we turned around. A simple set of MaxTrax (or any of several other suitable brands of sand track) would have given us the confidence to take the slight risk.

The JATAC on its modest tires and stock-height suspension might not have the brawny look of a taller sister truck on meatier tires, but we’re convinced it was the right approach for us and our intended uses. But I’ll be honest—if we change our minds, I’ll let you know.

Boss Global is here. Icon Vehicle Dynamics is here. Pronghorn Overland Gear is here. Maxtrax is here.

*Full disclosure: I consulted with Pronghorn on some final design details and proof of concept of their Wrangler bumper system.

Oil change: A simple job . . .

. . . unless you don't get the (separate) O-ring gasket lined up properly on the canister filter cartridge on your 300D. The O-ring is at the top of the filter housing, so I didn't realize it wasn't in correctly until I fired up the engine. It had in fact slipped completely down around the filter, leaving no seal whatsoever.

So this was the sight that greeted me through the windshield as I backed up the slope thinking I was finished. My own little Exxon Valdez. Pulled it back down, re-installed the O-ring properly. Now for some Simple Green and absorbent compound.

Just goes to show that a brilliantly conceived one-case tool kit does no good if you don't use the tools contained therein properly.

JATAC gets an outdoor kitchen

by Roseann Hanson (co-director, Overland Expo)

There's a lot I love about having a stove, sink, and fridge inside a truck camper—all-weather cooking, protection from mosquitoes, and the convenience of a full kitchen (see this article, about our "Just a Tacoma and Camper" setup). But I miss cooking outside. It's more social, and enjoying the views is why we explore and camp. Nothing like sipping a cool drink, tending some thick pork chops, and gazing out over the Grand Canyon while a condor soars overhead . . .

To facilitate outdoor cooking, we sorted out a camp table and awning. Jonathan rigged us a sleek and easy mount for the sturdy stainless steel table from Frontrunner Outfitters (see story here). And although it was initially a tough decision ($800), we invested in a high-quality, quick-deploying Fiamma awning for the starboard side. Importantly, this is also the side for access to the Four Wheel Camper's dual 10-pound propane tanks, since I settled on a propane grill, for convenience and when local fire restrictions or wood availability obviates our Snow Peak portable fireplace grill. My idea was to leave one tank hooked up to the inside stove and hot water heater, and the second tank rigged with a portable grill hose so all we had to do was hook it up and start cooking.

Now all I needed was a portable propane grill that was powerful, not too bulky, high-quality, and functional.

Easier said than done. I looked at many name brands, including Coleman, Char-Broil, Weber, and NexGrill (a sister brand of Jenn-Air). Some had great BTU ratings (the NexGrill boasts 20,000 and has 2 burners with separate controls). Some were clever (the Coleman Road Trip has an integrated stand that scissors down, so you don't need to use up valuable table space). Some were cheap (the Char-Broil at $30 via Amazon—with the savings you could buy a lot of top sirloin . . .). Some were compact (the Fuego Element closes like a sleek clamshell and is just 9x12).

But in the end my eye was caught by the Napoleon PTSS165P portable grill ($189 MSRP), built for the demanding marine environment (you can order very pricey sailboat cockpit mounts for it). Runner up was the NexGrill (model 820-0015, $180 at Home Depot) but reviews on Amazon indicated the finish quality was poor, with some users claiming not all parts are stainless, or were flimsy with sharp edges. The quality of the Napoleon looked so good, I decided to take a gamble on its 9,000 BTUs (compared to twice that for the NexGrill) and single burner control.

The finish quality of the Napoleon is beyond reproach: folded and riveted corners, smoothly finished vent holes, and sturdy (not at all "tinny") 304 stainless throughout.

Details like the high-quality latch and rivets won me over.

The four-inch legs are anchored with stainless bolts, and pivot flush to the bottom for storage. Only complaint: they do scratch the tabletop, so we're going to coat the bases in Plasti-Dip.

The handle stays cool even after long periods of cooking. However, it's on the wrong side for a right-handed person (when grilling, you usually hold a utensil in your right hand and would use your left to open the grill to check cooking progress). The pietzo-igniter stopped working after the first night. The propane regulator is also on this side. The Napoleon only comes with a mount for small 1-pound canisters; we had to buy a 5-foot hose to connect it to our 10-pound tank.

Cooking area is 17.25 x 9.25 and just about perfect for two people. For more food than that, cooking in shifts would be recommended. To get searing temperatures, the instructions recommend lighting the grill and pre-heating for 10 minutes. This did produce temperatueres just right for searing the pork chops. I do wish it had two burners so I could turn one off to create a cooler location for finishing things like vegetables.

The slightly domed lid is vented but very windproof (we cooked two dinners in 10-15 MPH gusts), and its height would allow cooking a small whole chicken or something in a deep-dish pan; you could even bake a cake or low-top bread. There is a slide-out grease trap tray on the bottom, which made clean-up super easy.

The carrying case fits well but its quality is not commensurate to the grill: the fabric is thin Cordura and is poorly sewn (on ours, the inside pocket for the gas regulator pulled out at the bottom), so I'm not expecting it to last as long as the high-quality grill.

We've now used the Napoleon half a dozen times on a 2,800 mile trip, and are overall extremely pleased with the quality. It's also transformed our camping by doubling our "living area" to include a spacious, convenient, shaded outdoor kitchen where we can easily grill salmon steaks, cook lasagna, bake a cake, or turn out bacon and pancakes on a griddle for a small group.

(Awning: Fiamma.com; table: FrontrunnerOutfitters.com or a similar version from K9 racks and Equipt Expedition Outfitters, available in three sizes)

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.