Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Transglobal Car Expedition gets a lesson in global warming

Back in March of this year I was horrified and angered to read the following headline on the Explorers’ Web:

“Transglobal Car Expedition Loses Vehicle Through Ice; Local Inuit Village Outraged.” (Read the article here.)

The vehicle was a Ford F150 prepared by Arctic Vehicles, first known for their fat-tired Icelandic Toyotas. The truck was part of a seven-vehicle fleet conducting a test run for something called the Transglobal Car Expedition, the stated purpose of which is to cross both geographic poles by vehicle, all on the surface (that is, no flights, only ship transport when necessary). The website also says— quoting verbatim here—“We believe that we can embrace the Earth by meridian by meridian and unite people all over the world in one common journey.” (The rest of the site exhibits similar egregious editing issues. End snark.)

Unfortunately, on this “common journey,” while crossing sea ice off the northwest coast of the Boothia Peninsula, in Canada’s Arctic, the truck broke through thin ice and began sinking. The crew was able to escape before the truck plunged the rest of the way through and went to the bottom in about 30 feet of water—while carrying “40 liters of fuel,” a backup generator presumably carrying its own fuel, plus of course the engine and transmission oils and fluids. (I wonder if the “40 liters of fuel” actually refers to jerry cans, and doesn’t include fuel in the main tank.)

The irony here is significantly thicker than the ice through which the truck sank. An expedition in the process of burning tens of thousands of gallons of fossil fuel to “embrace the earth” loses one of its vehicles through arctic sea ice—which is rapidly thinning and receding due to our overuse of fossil fuels.

According to West Hansen, an explorer whose planned sea kayaking expedition through the Northwest Passage will cross the path of the TCE route, the group failed to consult local residents about ice conditions. In fact, one of the putative side goals of the expedition (besides uniting people all over the world) is to provide local communities with data about ice conditions.

You read that correctly. With one pass through the area, the Trans Global Car Expedition will advise the Inuit, who have been living, traveling, and hunting in the region for thousands of years, about local conditions. The group actually issued this official statement regarding the incident: "It has also provided important data on the viability of travel on the ice in the context of global warming, which is making traveling over the ice more dangerous for Indigenous communities and other ice travelers.” One team member added, regarding the plan to recover the truck, “ . . . our respect for the land motivates our desire to do the right thing to remediate the area, and also bring the world’s eyes to one of the most pristine and beautiful places on the planet.” Is your irony meter now bouncing off the peg like mine?

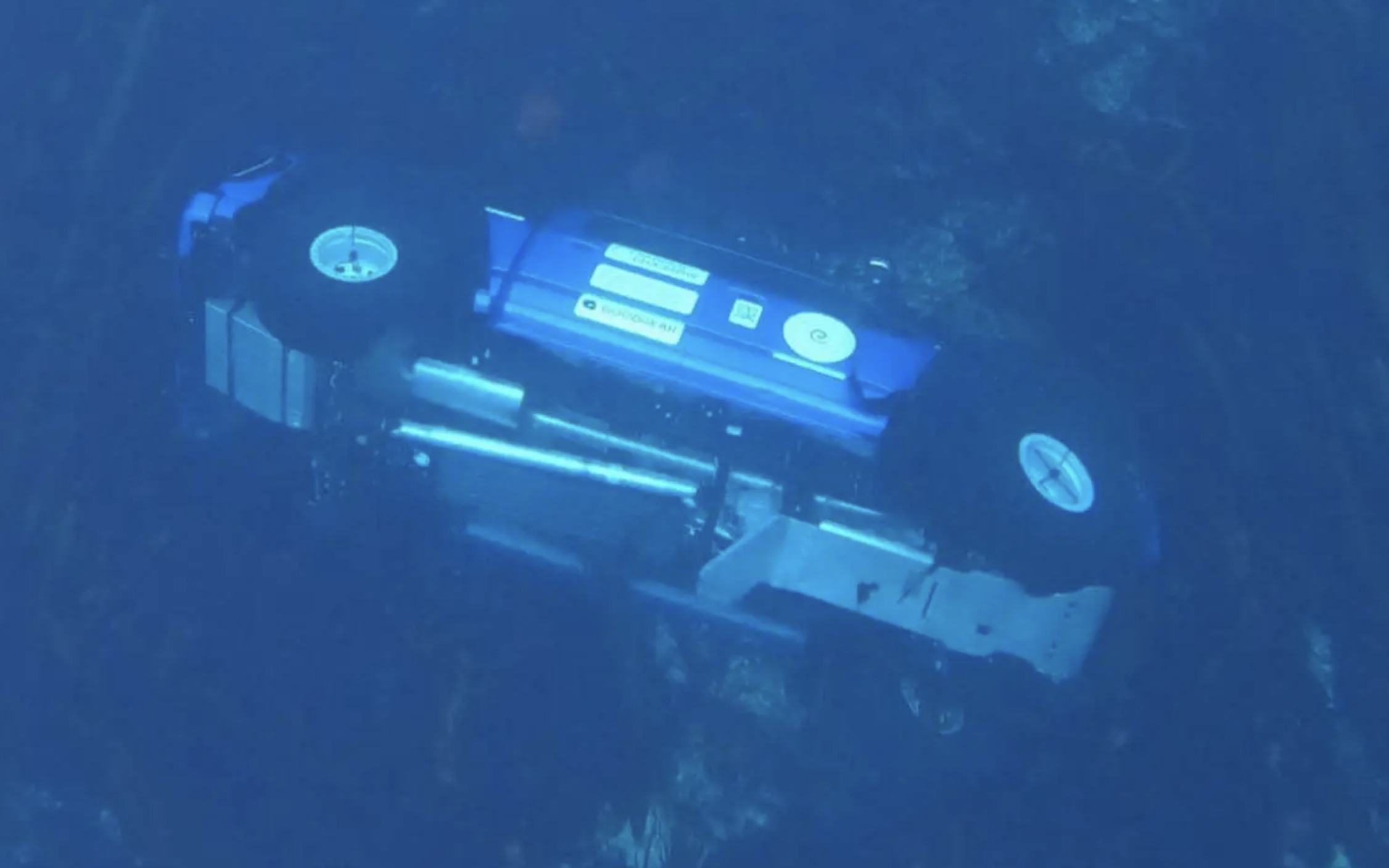

The remediation, sadly, did not happen quickly. The vehicle sat on the floor of the Arctic Ocean, in the densest layer of its subsurface life zone, for five months before it was brought back to the surface, so the recovery team could take advantage of better weather and ice conditions. In the meantime the truck was rolled around on the ocean floor by currents, and wound up in water twenty feet deeper than that in which it sank. Despite this, the team claims they recovered the truck “without any damage to the fragile ecosystem.” I guess we’ll have to take their word for it, although I find it difficult to believe a 7,000-pound truck rolling around on the sea floor wouldn’t do some damage, even if there was zero leakage of fluids.

Let’s back up and think about this entire endeavor. What will the Transglobal Car Expedition accomplish, assuming they complete the trip in 2023-2024 without losing too many more vehicles to thinning arctic ice?

Both geographic poles have already been reached, multiple times, on foot, unsupported (not even any generators along . . .). How does driving internal-combustion-powered trucks to those poles expand the envelope of human endeavor? Not only is there nothing scientific to be achieved, it is in fact a prominent middle finger to climate scientists, biologists, and local communities urging preservation of these sensitive regions. (I was stunned to discover that the National Geographic Society lent its status to this project, and I wonder if the recent debacle has given the directors any second thoughts.) Will the TCE “unite people around the world” as stated on the website? Sorry, but I think Coca Cola has a better chance of doing that. (To be fair to the TCE, several so-called “eco-tourism” companies are gleefully offering cruises via giant ships to formerly inaccessible areas of the Arctic Ocean, including complete transits of the Northwest Passage.)

For just one example of the outsize impact the TCE will have on the planet, consider the single flight mentioned in the linked article. The Dassault Falcon 900 jet Russian oligarch Vasily Shakhnovsky, the apparent patron of the TCE, used to (illegally) fly to Canada to visit the team holds 3,000 gallons of JP5 jet fuel, giving it a range of 4,700 nautical miles. I’ll leave you to estimate the total amount it took to fly one man to and from Canada. (This, as well as the helicopter recovery of the Ford, also makes moot the expedition’s claim that it will use only “surface transportation.”)

Let’s back up some more. Vehicle travel—whether for personal enjoyment or ambitious, hugely financed “first-time-ever” goals—can be considered a single very large, graduated gray area. At the pale end of the scale we wouldn’t drive anywhere. But most of us reading this live in the real world, and realize that retiring to live in a cave, as the more dullard anti-environmentalists like to urge environmentalists to do, won’t solve anything. Individual and small-group travel by vehicle, as anyone who has done it knows, actually is one very effective way to genuinely “unite the world.” Thus we accept a status somewhat farther along the gray scale.

But a massive “expedition” pursuing a spurious “first” and attempting to justify it with an even more spurious scientific or “world peace” agenda lies, if you’ll forgive me, at the polar opposite end of that scale, in a very, very dark region.

Edit: After I posted a link to this story on Facebook, I received a polite and measured reply from Andrew Comrie-Picard, one of the TCE team members who was on the recovery effort for the Ford pickup. He went to lengths to assure me that the team did in fact take every precaution to minimize damage to the ecosystem, and said that fluid leakage from the vehicle had been minimal. I appreciate his information, although it does not change my opinion regarding the irony of the accident, or the massive overall impact and resource consumption of this effort, for a dubious goal.

The capable, comfortable Mitsubishi Delica

The third-generation Mitsubishi Delica van, produced from 1986 to 1994, has become well-known as a reliable, economical, and capable micro-motorhome for travel. Since the entire model run is now available for import to the U.S. under the 25-year rule, I’ve been seeing more of them titled here.

The Delica (the name was a mash of “Delivery” and “Car,”) was originally offered in 1968 in several variations including pickups, and went on through several succeeding generations after the third, but the 86-94 version—with unibody construction, available four-wheel drive with low-range and a center diff lock, a solid rear axle, and efficient diesel and turbodiesel engines, is the affordable sweet spot for overlanders looking for something different and attracted by the idea of a compact self-contained camper. The aftermarket has responded with numerous accessories and modifications, right up to and including larger turbos and brakes. The 2.5-liter, four-cylinder RD56 diesel is known for longetivity and good economy if not outright power: The later factory intercooled version was rated from around 90 bhp and 177 lb-ft up to 115 bhp and 182 lb-ft. Transmission was either a five-speed manual or a four-speed automatic.

I’ve seen several Delicas with ingenious origami interior designs that managed to fold in comfortable sitting, sleeping, and cooking arrangements. This one was parked outside Beaver Sports in Fairbanks, Alaska. Unfortunately I missed talking to the couple who was driving it, but it looked well-sorted and well-used.

Running low on VDEGs . . .

We are down to fewer than two dozen copies of the bible of overland travel, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide, and I have no word when or if we will receive more copies. If you’ve been contemplating buying a copy please don’t hesitate!

Truck, or travel?

Years and years ago I met a fellow who was building a sailboat. (Trust me, this is relevant.)

The boat was a Westsail 32, a legendarily seaworthy cutter known for its ability to comfortably bulldoze its way across any ocean and through any storm (although it was not known for doing so quickly.) Its design descended directly from the stout, double-ended Norwegian life-saving vessels designed by Colin Archer, who also designed the Fram, perhaps the most famous arctic exploration vessel in history.

The Westsail 32 was sold as both a complete boat and as a bare hull and deck, and in the early 1970s hundreds of would-be globe-girdling sailors on budgets bought shells containing little but a few tons of hand-laid fiberglass and dreams. Many of those hulls were completed and went on to actual globe-girdling duty. Others enjoyed a year, two, or five of enthusiastic attention, then slowly grew neglected, dusty and moldy before being sold off at a loss as an “easily finished project.”

Charlie’s Westsail did not suffer from neglect. Far from it. When I met him—which happened because I spotted the boat in his back yard on a bike ride, recognized it instantly, and knocked on his door—he was, if I recall, in his tenth year of ownership and the thing was nowhere near ready to launch. The reason it was not ready was because Charlie insisted on nothing but the very finest craftsmanship for his boat, and nothing but the finest fittings. As a semi-retired welder, he had plenty of time to devote to craftsmanship, but as a semi-retired welder he had to purchase major items such as the mast, the auxiliary diesel engine, the teak for the deck, and numerous others, one at a time, with lengthy gaps to replenish the bank account.

I asked him if he’d considered non-slip for the deck rather than teak. Nope, had to be teak. A used low-hours Volvo diesel instead of a new one? Nope. I couldn’t argue with him, because this Westsail was a work of art; every single component perfect, the interior joinery so flawless I despaired of producing the like if I ever built my own boat. Or bookcase, for that matter.

The problem was, Charlie was ten years and one heart attack older than he was when he bought his hull and deck. As I watched the glacial pace of his build, helping occasionally with awkward work such as laying countertop laminate, I began to wonder if Charlie would ever see anything but his neighbor’s yard from the cockpit of this beautiful sailboat.

And what, you ask, was the denouement? I’m ashamed to say I do not know. At some point I became “caught up in the gale of the world,” as the saying goes, with work, our move to a wildlife refuge as caretakers, and other things that should not have gotten in the way of staying in touch but did. I finally went back four or five years later; the boat was gone, so was Charlie—the new owners of the house knew nothing about him. I could only hope he made it to the South Pacific in his Westsail and found a deserted isle shaded with coconut palms.

Okay—I realize this is a pretty dramatic corollary to prepping a truck to go camping. But long ago I lost count of the people I’ve met who have put so much time, energy, and money into “preparing” their vehicles for epic trips that they’ve not yet gone anywhere, or at most have logged a few weekend jaunts. The dreams are always there: “Yes, planning to do the Dempster.” “Heading for South America next year.” “Baja.” “Alaska.” “Tanzania.” Easterners scheming to go west, westerners eyeing Nova Scotia. One newlywed couple at the Overland Expo was planning to leave from the show to drive around the world; I don’t think they’ve made it off this continent yet.

Why does this happen?

I know a lot of 4x4 owners derive nearly as much satisfaction from the planning and building as from the traveling itself (I’m quite sure this was part of Charlie’s attitude). Other owners—men in particular, in my experience—simply cannot leave any object alone if there are accessories available for it, especially if they can remotely be described as “functional.” Accessorizing and modifying becomes the end, not the means. But a subliminal fear of actually embarking also can easily cultivate a long list of “Oh, I need this” modifications that must be done beforehand—new roof tent, winch, solar array, some of those stylish externally mounted Rotopax fuel cans, driving lamps . . . the list is long.

Many, many other people, however, are ready and willing to go, but have been convinced by magazine articles, advertisements, and forums that they really do need all that stuff. I was reminded of this just the other day when, on a post someone had written about driving the Dempster highway to Tuktoyaktuk, one respondent asked, “What suspension did you install?”—as though some hyper-sophisticated aftermarket setup with progressive-rate springs and external-bypass shocks was a legal requirement before even contemplating such a journey.

Suspension? You don’t need specialized suspension to drive the Dempster Highway. Or the Dalton Highway. Or the Mojave Trail, or the Connie Sue Highway or Ruta 5 or the Skeleton Coast, for that matter—unless you’ve overloaded your vehicle with a lot of other stuff you probably don’t need either.

Don’t get me wrong. I have absolutely nothing against those who farkle their vehicles until the actual silhouette of it is barely recognizable (as long as they’re within GVWR, of course . . .). No one has been more intimately involved with promoting overland travel and its associated equipment in the last two decades than I. And the—shall we say exuberant?—proliferation of products to serve that market has been astonishing to watch.

But, as my friend Tom Sheppard says, “Horses for courses.” It’s good to learn to recognize the difference between what you really need and what someone tells you you need—and also between what you really need and what you really just want. If you build an exhaustively equipped overland vehicle and then happen to drive the Dempster in it, great. But if you build it to be able to drive the Dempster, you’ve wasted your money, and if you put off driving the Dempster until the vehicle has every possible modification completed, you wasted time you could have spent exploring.

Here’s a personal example. In 2016 Roseann and I bought a mostly stock 1993 HZJ75 Troop Carrier in Australia, sight unseen. We had plans to convert it to a fully equipped camper, but we also had time to visit Australia the next month.

The ad photo for our HZJ75

So we had the vehicle shipped to the Expedition Centre in Sydney, where they had just barely enough time to install a pop-top before we arrived. Our friends Graham Jackson and Connie Rodman had bought their own HZJ75, and picked theirs up totally stock. We bolted a fridge in each vehicle, strapped a chuck box in ours, bought cheap 20-liter water cans and foam mattresses, and drove both vehicles halfway across the continent to Alice Springs, crossed the Simpson Desert along the Madigan Line, visited Birdsville, and circled back to Sydney. We left our Land Cruiser at the Expedition Centre again, where they installed cabinetry, a 25-gallon water tank with pressure, a batwing awning, and a few other items. The next year Roseann and I flew in and drove around Tasmania, crossed back and visited the Flinders Range, Coober Pedy, and Uluru. The year after, Graham and Connie—who by now had their own pop-top and water tank—joined us again, and we drove all the way across Australia, shipped the vehicles to Africa, and continued to the Atlantic coast.

And as it is now.

Did we have more fun the second and third year than the first? Heck no. Sure, we were more comfortable, and camp was easier to set up. But it wasn’t more fun, and nothing we’d added was essential to completing our routes. More important, if we’d waited to have everything finished before we went we would have missed an entire year of exploration.

There are a few modifications I consider essential for remote travel—good tires, a dual-battery system, and just a couple others. Beyond that, there are a whole bunch that are nice to have—but not one that should be a substitute for actually getting out and traveling. As always, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide is a good resource for sorting out the must-haves from the marketing.

Catastrophic engine failures in 2021 Ford Broncos

I’m really glad this didn’t happen to the Bronco I reviewed earlier this year.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is investigating a series of engine failures in 2021 Ford Broncos equipped with the 2.7-liter V6 engine. The issue (according to Ford) apparently involves faulty valve keepers, which can come loose, in turn allowing the valves to impact the piston, with predictably unpleasant results.

The investigation encompasses over 25,000 vehicles, and began following complaints by 32 owners who experienced abrupt losses of power in their new V6 Broncos—undoubtedly accompanied by predictably unpleasant noises.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Ford has 45 open recalls so far in 2022, more than any other U.S. auto maker—in fact nearly twice as many as the second place manufacturer, Daimler Trucks North America.

Another hitch-ball "recovery," another fatality

(Full disclosure: I pulled this information and images off the Montana Overland and 4x4 Adventures Facebook page, and the Mojave County 4x4 Recovery page. I felt it was justified given the gravity of the event and its lessons. Thanks to Dave Anderson for the heads up.)

Ryan Robert Woods was killed when part of a hitch-ball assembly that broke free during a kinetic “recovery” flew back through his windshield and impacted his head. He had been driving his Ford Super Duty through a local, muddy play area when he became stuck and called a friend for assistance.

At first I thought, Here we go again. But on reading more details the situation was even worse than it seems. Ryan’s friend (reportedly an experienced 4x4 driver and racer) not only made the grievous mistake of using a hitch ball as the anchor point for the strap, it was a drop hitch, with a ball positioned a good ten inches below the receiver. This created a massive multiplication of force due to the leverage involved when the strap snapped taut. As you can see from the photo below, the entire assembly broke off at the receiver, creating a projectile easily ten or fifteen pounds in weight.

But even that’s not the end of the mistakes made here. According to the post, the strap was not a proper, nylon, kinetic strap with designed-in stretch, but a non-elastic polyester tow strap.

To complete the tragedy, Ryan’s wife of 23 years, along with their three children, were in the truck with him when he was killed. They will have to live with that scene in their heads for the rest of their lives.

Don’t use hitch balls for recovery purposes. Any recovery purposes. And don’t use non-kinetic straps for kinetic recoveries. Even if you’re towing someone across a parking lot, a kinetic strap or rope provides an extra measure of safety.

The Dometic CFX3-35 fridge: simple, perfect function

Roseann and I have owned our share of vehicles incorporating all the overlanding “mod cons,” as the Brits would say: Four Wheel Campers with internal showers, water heaters, dinettes, queen-size beds, fridge and sink, etc. Our HZJ75 Troop Carrier likewise has a pop-top with bed, cabinets, stove, fridge, pressure water, a 270-degree awning . . .

Last August and September, however, when we traveled to Alaska in part to do research for my second novel, we couldn’t drive up due to the continued border closure with Canada. Instead, we flew to Fairbanks with a lightweight camping outfit and rented a Suburban. And on a trip up the Dalton Highway we rediscovered the joys of basic camping. We slept (very comfortably) in the back of the vehicle in sleeping bags on top of Thermarests. We used a small single-burner stove for cooking, and we carried a 10x10-foot silnylon tarp for shade and rain protection. We did miss having a fridge, but otherwise the simplicity, and freedom from numerous complex infrastructure systems, had its own kind of attraction.

Thus, after buying a cool old cabin in Fairbanks and purchasing a 2014 Tundra for an Alaska vehicle, we decided (for the moment, at least!) to stay simple with this one. We bought a “Double Cab,” in Toyota speak—actually more like an extended extracab with a 6.5-foot bed—so we can sleep in the back. In the interests of fuel economy we installed an A.R.E. cab-height fiberglass shell, which still offers plenty of sit-up headroom. Further enhancements will be evaluated on an as-needed-or-desired basis.

One thing we didn’t want to do without was that fridge. Even in Alaska, the freedom from the ice-refill chore is a blessing. (Try buying ice along the 400 miles of the Dalton. Go ahead.) But in keeping with our semi-minimalist philosophy, we didn’t want an 80-liter National Luna with separate freezer compartment. All we wanted was room to keep beer and white wine cold, along with milk and cream, fresh vegetables, and meat. I wanted it to fit behind the driver’s seat of the Tundra with the 2/3 back seat flipped up. And I didn’t want to spend $2,000.

I found exactly what I wanted at Dometic. I’ve been paying more and more attention to the company in the last couple of years, as they’ve been introducing an avalanche of outstandingly well-designed new products, from fridges to chairs and tables and a clever water-carrying system, all of which actually stand out in a marketplace overfilled with undistinguished offerings.

The CFX3-35 is in many ways a throwback to the early days of the Engel, even though it supports a Bluetooth capability I’ll never use. The flat, step-onable lid incorporates a simple lifting latch—lift the latch and lift the lid. It opens lengthwise and lengthwise only. The spring-loaded handles also serve as tie-down points—no need for an optional kit. The display is clear and the controls make the owner’s manual redundant. An interior LED illuminates better than most interior lights I’ve used.

I drilled and bolted suitably strong tie-downs to the rear seat bases in the Tundra, using my favorite all-around tie-down loops: the comically named Canyon Dancer strap rings. (I did a real torture test of these here years ago. Forget the outdated links and just Google them if you want some. I keep a dozen at a time on hand because I’m always finding applications for them.)

To ensure the fridge remained powered without endangering starting capability, I installed a Genesis dual-battery kit, which fits entirely within the stock battery placement of any 2008-2021 Tundra. Look for a review soon.

On my subsequent 4,000-mile drive to Fairbanks (solo; Roseann was teaching a field arts class in Wyoming) with a cargo trailer full of household goods, the Dometic did just what it’s supposed to. I had cold beer or wine each night, cold cream for coffee and cold milk for cereal in the morning, and cold cold-cuts for lunch. Luxurious. (Speaking of luxurious, I slept in the back of the truck in one of Born Outdoor’s Badger Beds, about which much more later. In fact I’m still sleeping in it while I sort out the cabin.)

At under $1,000, I think the Dometic CFX3-35 is a solid buy. The line of course includes many other sizes, along with dual-zone units if you desire freezing capability along with refrigeration.

Dometic is here.

High-temperature-tolerant, winch-capable LiFePO4 batteries from DCS

Back in the late 1990s I wrote a review in Outside magazine comparing compact 35mm cameras with the new generation of digital cameras, which were just becoming practical alternatives for casual use. (Some of them employed sensors that were breaking the miraculous one-megapixel barrier.)

At the end of the review, I noted that digital images could not match those from 35mm film—but I predicted that someday they would, and that digital photography might eventually eclipse film imagery.

The editors cut out the prediction part because, they said, it was pure conjecture and they didn’t want to annoy advertisers who manufactured only film cameras.

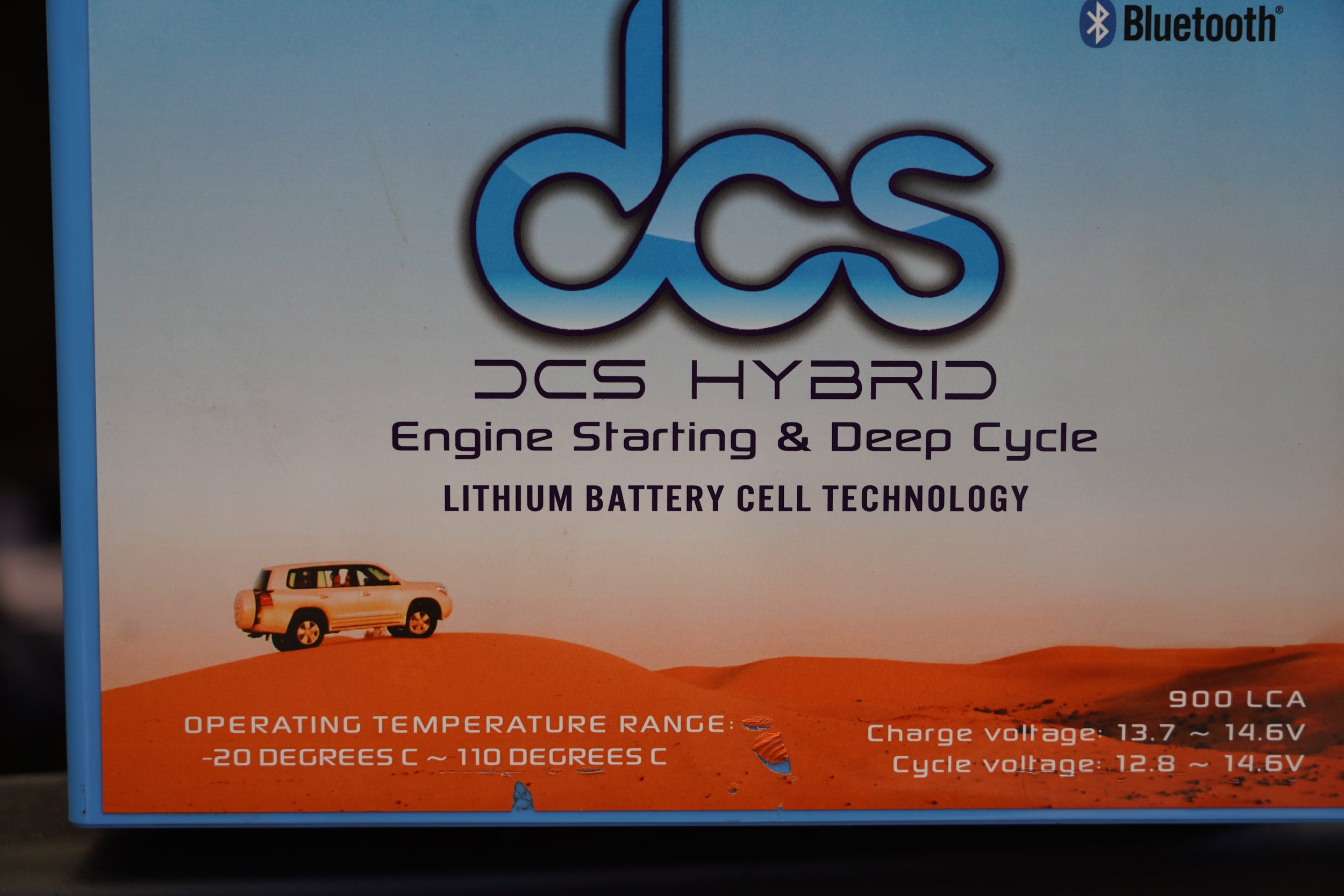

That was then; this is now: I have my own site and no editor to veto predictions. But I think my next one is easy: For the serious overland traveler, LiFePO4 or LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate, or just “Lithium”) batteries are on the way to becoming the standard power source for “house” batteries—that is, those used to run fridges, lights, inverters, etc.—and probably for starting and winching use as well.

The reason is not the one most commonly cited—weight savings—even though replacing two AGM batteries with Antigravity LiFePO4 starting and deep-cycle batteries in our HZJ75 Troop Carrier almost exactly offset the weight of our National Luna Weekender fridge/freezer. The real advantage to lithium cells is their far higher energy density and flat power delivery compared to AGM or SLA batteries, combined with a discharge/recharge lifespan far, far longer than AGM batteries—enough to completely amortize the higher initial cost and then some. On top of that is their ability to accept charge at a far higher rate than possible with lead-based batteries. Please read this first if you’re not familiar with these characteristics.

Note that I wrote “on the way to becoming,” not, “have become,” because until now LiFePO4 technology has had a couple of significant drawbacks compared to AGM batteries.

I don’t count the higher price, since as mentioned a buyer can expect to recover the difference fully in extra lifespan. The two main drawbacks of current lithium batteries are, 1) their sensitivity to temperature extremes, both hot and cold, and, b) their inability to deliver the kind of extended high amperage needed for winching use.

However, just as with digital imaging, we can expect manufacturers to continue innovating and expanding the capabilities of LiFePO4 technology. And one of the first companies doing so is the Australian company DCS (Deep Cycle Systems), distributed in the U.S. by Carl Jonsson at Tiktaalik. I recently had a couple of weeks with one of their combination starting/deep-cycle batteries, and hope to do a full review of a dual-battery system this fall.

What’s improved on the DCS battery? Most LiFePO4 batteries can only accept a charge at temperatures between about 25ºF and 125ºF (-4ºC to 52ºC), and can only discharge (produce power) at temperatures between -4ºF and 130ºF (-25ºC to 55ºC). The DCS battery has similar lower limits, but it will accept charge at temperatures up to 149ºF (65ºC) and can produce power at a scorching 230ºF (110ºC). I consider that a massive jump in performance parameters, especially if, as I, you live in a desert.

Additionally, DCS offers an “Extreme” version of their basic model, designed for “military and naval applications,” and advertised as “well suited for engine bay installation and winching applications.” That would be another massive jump in performance. I can hardly wait to hook up the FJ40’s Warn 8274 to one of those and give it a workout on a training weekend.

As is the norm with so many products recently—especially those produced on other continents—Jonsson is striving to ramp up availability on a full line ranging from a single 50AH battery to a 260AH dual system. Find out more and keep an eye on incoming stock at Tiktaalik, here.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.