Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Save the tall sidewalls!

Take a look at the tires on this truck. I did not stop to see what size they were, as I was afraid the owner would appear and I’d have to pretend I was admiring the thing. And my iPhone snapshot won’t blow up enough to read the sidewalls. The wheels were certainly 22s at minimum. The aspect ratio on the tires couldn’t have been more than 30 or 40.

I don’t know why a tire manufacturer would bother making an aggressive mud-terrain tire with a sidewall no more than two inches tall. (Well, I guess I do know—they sell.) But the combination not only makes no sense, it’s hugely detrimental to even poseur street-only driving. These tires will be loud, they’ll ride poorly, they’ll reduce fuel economy, they’ll have poor lateral grip, and they’ll increase the potential for wheel damage, both curb rash and possible failure if the driver hits a curb or other obstacle. (I won’t mention the silly spiked lug nuts except to offer an exaggerated eye roll.) If this fellow actually tried to tackle the backcountry with these tires he’d risk severe tire and wheel damage, and would be unable to air down at all to increase traction or flotation.

This Chevy is obviously riding on aftermarket wheels. Sadly, however, factory wheel diameters are on the way up too, even on vehicles advertised for their off-road capability. Seventeen-inch-diameter wheels are now on the small side; 18s, 19s, and 20s are more and more common. The new Land Rover Defender has no wheel option under 18 inches, even with the steel wheels on the base model. The smallest wheels available on the new Bronco are 17s, as on the Wrangler Rubicon.

Why is this important? A taller sidewall conveys numerous advantages once you leave the pavement. Tires with an aspect ratio of 75 to 85—that is, with a sidewall 75 to 85 percent as tall as the tread is wide—can be effectively aired down, providing more grip on loose surfaces and rocks, and lengthening the contact patch to increase flotation in soft sand. The tall sidewall protects the wheel rim from impacts, and enhances ride quality. Should you lose a bead in the backcountry, or need to dismount the tire to repair a punctured or torn sidewall from the inside, a high-aspect-ratio tire is far, far easier to reseat in the field with a portable air pump.

Of course, you can still have a tall aspect ratio on a larger-diameter wheel if it’s also a larger-diameter tire, such as on some full-size American trucks. The Ford Tremor comes with 18-inch wheels, but the tires are 35 inches tall and have a decent aspect ratio of 75. You’d have a difficult time fitting 35-inch tall, 75-aspect-ratio tires on the Defender’s 18-inch wheels.

The corollary to increasing wheel diameters is, maddeningly, a reduction in the choice of 75 to 85 aspect tires for 16-inch wheels—for decades the preferred wheel diameter for serious remote travel. Nevertheless, there are still plenty available, especially from the makers who recognize the value of the size.

If you’re shopping for a new truck in which you plan to travel extensively off-pavement, look through the option list carefully and choose the smallest-diameter wheel that is available with the other options you want. Unfortunately, the more highly optioned the vehicle, the more certain it will also be saddled with large-diameter wheels. It’s worth checking to see if smaller aftermarket wheels will fit if you’re stuck buying your dream vehicle with fancy 20 or 21-inch factory alloys. The limiting factor is likely to be the diameter of brake disc and caliper.

Last 40 VDEGs

We have run out of our stock of the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide in the U.S., and Tom Sheppard is down to around 40 copies in the UK.

If you have been considering purchasing a copy, it might be a smart move to do so now, as we are not sure when there may be another print run. You’ll have to order directly from Tom at Desert Winds Press (here); however, the exchange rate is currently so advantageous for Americans that even with overseas postage the book will cost you barely more than when ordering it from us at Exploring Overland. Note: Please contact Tom first via email to confirm availability and postage, etc.!

You can, of course, still order Tom’s Four-by-Four Driving (to which I contributed two sections) directly from us at an advantageous price, here.

I'll see your Snow Peak titanium utensils, and raise you . . .

I’ve always loved the evocative air that surrounds traveling utensil sets, from my first Boy Scout knife/fork/spoon (excellent) up to the latest Snow Peak titanium kit (lightweight, and excellent except for the knife, which is comically useless on anything tougher than butter).

Along the way I’ve owned others and tested many more. Some were good, some bad—don’t get me started on the unholy abomination that is the “spork,” a failure at being either an effective spoon or a fork.

But no traveling set I’ve tried could be described as elegant.

Until now, that is.

I was down one of those internet rabbit holes that are impossible to trace backwards, but somehow wound up on eBay looking at an interesting silver-plated kettle incorporating a spirit burner, from Barker Brothers of Birmingham, England, a highly respected 19th-century maker. It looked like something that would be useful for our place in Fairbanks to keep tea and coffee water close to a boil. Intrigued, I searched for more of their products—and about halfway down page two a title jumped off the page and hit me between the eyes: “Victorian gentleman’s traveling silverware set.”

Inside a worn, leather-covered, hinged wood case, nestled in blue velvet and satin, lay a beautiful, bead-edged, full-sized silver-plated fork and tablespoon, accompanied by a steel knife with a faux-bone handle. The pièce-de-résistance was a silver-plated napkin ring—because, after all, what kind of savage travels with his own silverware but no napkin ring?

The ad noted that the case had an issue with the catch, and, perhaps because of that, the price was astonishingly affordable. Done.

In person it was just as glorious as in the photos, and a two-minute tweak with my needle-nosed pliers had the catch working fine.

Roseann’s reaction was exactly the same as that of several friends: “That is so you.” Accompanied by just the slightest smirk and eye roll.

I don’t care. As long as I’m not blowing through my vehicle’s GVWR, what’s the harm in adding a bit of class to the camp ware? We already carry pint glasses made of real glass in preference to the plastic things that go all hazy, and ceramic coffee mugs rather than tin.

I wonder if I could talk Roseann into a modest set of Wedgwood traveling china?

A cozy Daihatsu camper

There was a wide variety of overland-ready vehicles at the recent Armchair Adventure Festival, held just outside Plymouth, England: Several Defenders (including Toby Savage’s much-modified Carawagon, the veteran of many Sahara journeys), some pop-top vans and VW Transporters, and a spectacular six-wheeled Steyr-Puch.

But my favorite was this diminutive Daihatsu van, a model amusingly enobled by the company with the title “Gran Max” (it’s also sold as the Toyota Town Ace and Lite Ace). Within its Lilliputian dimensions (barely 5.5 feet wide and 13.3 feet long—a foot and a half narrower and three feet shorter than a current VW Transporter) the owner, a friendly young woman named Tuesday, had tidily fit the following:

Cabinet

Cooktop

Sink

Fridge

Folding 36-inch-wide bed

Storage underneath

A cassette toilet

And, of course, it has full standing headroom with the roof raised.

Did I mention it also has four-wheel drive? With a locking center diff?

Even with the additions, the van probably weighs under 3,200 pounds—less than half our HZJ75 Troop Carrier. I didn’t ask, but with a 1,500cc four cylinder (petrol) engine, a five-speed transmission, and the frontal area of a refrigerator, it likely gets twice the fuel economy as well.

Tragically, I missed the owner when I went back to snap the interior, but I can tell you it had all the room a single traveler needs, and would easily work for a couple who liked to spoon at night, or had a small tent.

You can see how the Gran Max compares to the VW Transit next to it.

The homely, perfect chuck box

As a contributor to somewhere around two dozen magazines over the past three-plus decades, I’ve been lucky enough to sample and own a wide variety of camp kitchens, from simple Coleman stove stands to the excellent Kanz Kitchen and the over-the-top, multi-component Iron Grill system from Snow peak.

Despite all that, the one you see above is still my favorite.

Why? Not because it’s the “best,” although it functions exactly how it’s supposed to. Certainly not because it’s the most expensive—in fact it is undoubtedly the cheapest camp kitchen I’ve owned. It’s my favorite because I made it back when Roseann and I were penurious college students, exploring the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico in our FJ40 and, later, an FJ55. Thus, even though subsequent kitchens saw far more exotic destinations, this one contains more precious memories than all of them put together. Like the night we were camped in Mexico’s Pinacate volcanic region when a meteor streaked overhead and its smoky trail covered half the sky. Or any one of several trips to the Sonoran coast of the Gulf of California recording nesting territories of least terns. Or leading sea kayak trips to that same coastline, towing boats and everything needed for excursions out to Isla Tiburón. Or a cross-country skiing trip to the Grand Canyon’s North Rim, when a blizzard hit and our trip leader got hopelessly lost next to a 4,000-foot chasm in ten feet of visibility.

I built the chuck box long before Youtube videos on such things, and so simply used my decent grasp of carpentry and Roseann’s concept to form it out of a single sheet of half-inch plywood. No fancy dovetails; it was simply glued and screwed together (and hasn’t loosened a millimeter since). I made sure to apply four or five coats of varnish, so the finish is still intact as well, despite numerous nicks and scratches. A drawer held utensils, matches, and can openers, the drop-down front created a table, and cork lining reduced rattles.

In recent years, with a succession of fancier kitchen systems from with to choose—not to mantion built-in kitchens in our Four Wheel Campers and Land Cruiser Troop Carrier—the chuck box got tucked away in a high corner of the storage building at our desert cottage, like the forgotten Velveteen Rabbit. When thieves broke in while Roseann and I were in Alaska last fall (by the simple expedient of hot-wiring our Ford truck and driving it through the wall), they took nearly everything . . . but left untouched the plain plywood box in the corner.

And, happily, just like the Velveteen Rabbit, the old chuck box came to life again. When we bought a 2014 Tundra to use as our Alaska vehicle, we decided—for the moment, anyway—to keep the camping setup simple. So when I hauled a trailer full of household goods to Fairbanks, I strapped the chuck box in the bed of the truck, and found that it worked just as well as it did 30 years ago. I didn’t miss those fancier kitchens one bit.

The Toyota Hilux gets . . . gasp . . . rear disc brakes

Toyota has announced a new Hilux model, the Rogue—naturally not for us, just our lucky Down Under mates. Along with 140-millimeter-wider front and rear tracks, the Rogue will finally shoulder its way out of the pre-Cambrian muck and be fitted with rear disc brakes, as every competitor has been for at least the last ten geologic epochs.

You might have read my comments on the 2016 Tacoma and its retention of a century-old braking system, along with Toyota’s fatuous justification for keeping them, way back here. The world-market Hilux also remained stuck with rear drums. Now, finally, Toyota has leaped into the latter half of the twentieth century—at least on this version of the Hilux.

Will the Tacoma follow suit? I cannot imagine Toyota keeping up the charade that “drum brakes are better off road” for much longer.

Will an upcoming Tacoma also benefit from a return to a fully boxed chassis, as the Tundra has done (and the Hilux has retained all along)? Or is that too much to ask?

Cross-winding synthetic winch line—yea or nay?

Like more experienced people of my acquaintance (you know who you are, Jim), I’m hyper-vigilant about spooling my winch lines correctly.

There are solid practical reasons for this: A winch line that is spooled neatly, tightly, and under load is far less likely to kink (if steel) or snarl, and there is less risk of the line diving down through the wraps below during a strenuous recovery. A neatly and tightly spooled winch line is smaller in overall diameter on the drum than a loosely and sloppily spooled line, thus retaining more of the winch’s rated power. During most straight winch pulls, a properly spooled winch line will practically re-spool itself automatically as it follows the path of least resistance across the drum. Finally, if you’re ever forced by circumstances to pull out your line all the way down to the bottom layer during a recovery, those tightly spaced first few wraps are less likely to slip.

However, I have to admit something: There’s also a significant OCD component to my own diligence. I can’t sleep when I get back from a trip or training until I know that winch cable is restored to perfect alignment. A winch cable lined up in snug parallel rows like a Marine drill team—or the Rockettes, take your pick—just looks so much better than, well, this:

Please pause while I catch my breath.

(Of course, ironically, a winch that’s been bolted on strictly as a poseur accessory, with factory-spooled line, will look just as tidy. We must then count on our frayed and faded Dyneema and well-burnished eyelet or hook to set us apart as real users.)

For years I preached the gospel of properly spooled winch line—at the Overland Expo, during NPTC evaluations, in private training sessions, and on guided trips. The total of my converts surely rivaled that of an obscure middle eastern carpenter from a few centuries back.

Then, recently, horror struck.

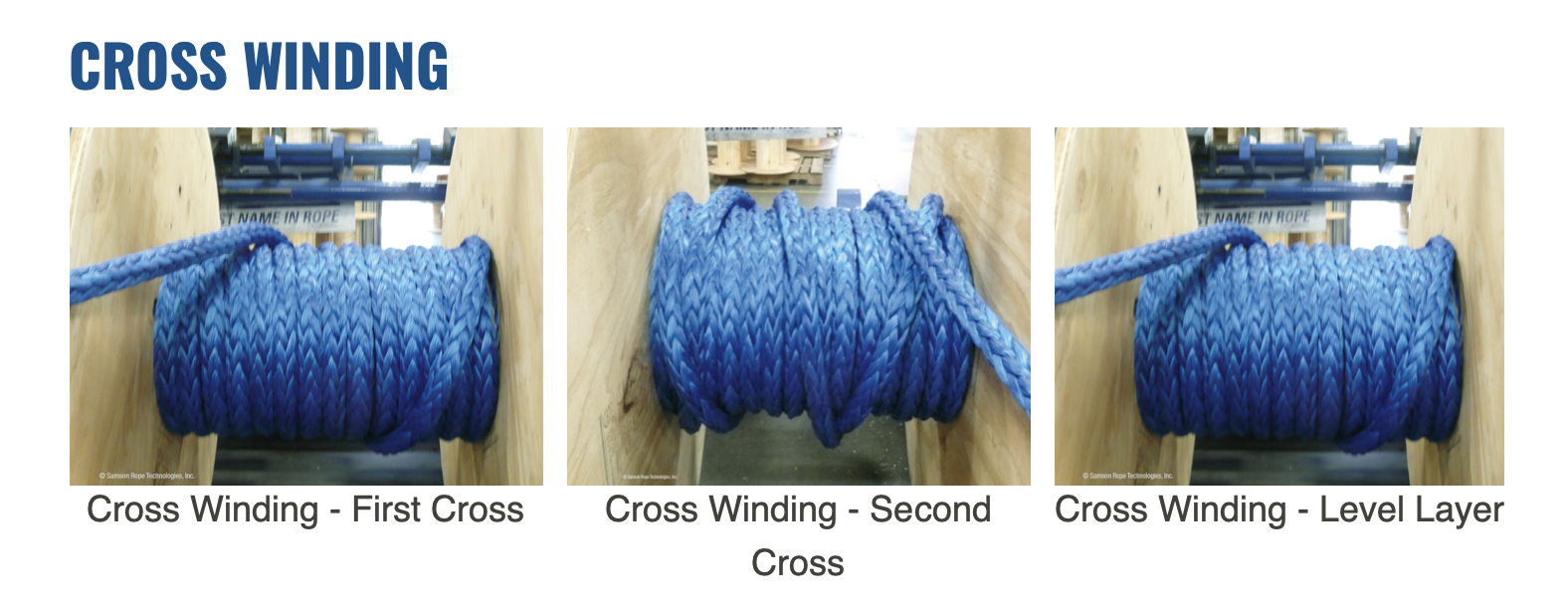

On a random day on a random overlanding forum, I came across a post titled something like “Cross-winding your winch cable.” The author of the post—clearly a goat-horned demonic agent sent from the Underworld—claimed that by spooling one’s winch cable in great angled swoops across the drum, the chances of the line diving were eliminated, since the line was never layed parallel.

There was a photo.

OMG.

My stomach lurched. My pulse jumped. It was . . . indescribable. Lazily spooled winch lines were nothing compared with this . . . this deliberate travesty.

Staring at the awful image, I tried to calm myself. With shaking fingers I straightened my computer on my desk. I straightened my phone. I lined up my pens, my flashlights, my knives. They were all already straight but I straightened them again. I re-coiled my Macbook’s power cord into a perfect whorl. Was my desk crooked? I nudged it into perfect alignment with the floorboards.

It didn’t help. I needed a drink. I stumbled to the kitchen. Daiquiri? Its elegance and mathematical symmetry (2:1:1) beckoned. Clumsily I gathered the components—no, this was taking too long. I flung the top off the crystal decanter and chugged directly. Rum ran down my chin and spilled onto my shirt, onto the countertop. I licked it up. Oh the degradation. I tried to slow my breathing.

Okay . . . better.

Back at the computer, I replied to the goat-horned demon, politely, that no one should consider trying such a “technique,” and that no professional would recommend it.

The GHD responded, “Oh really? How about this then?” And included a link to a page on the Samson Rope website.

I felt a queasy stirring of doubt, but clicked on the link—and there, on the website of one of the most respected makers of rope and winch line on the planet, was a series of photos explaining how to cross-wind synthetic winch line when spooling it.

I wondered briefly if nitroglycerin pills were available over the counter.

Instead I looked around the web, and found another reference to cross-winding from the Australian company Schillings, and in fact uncovered mentions of the practice in forum archives from over a decade ago.

Okay. Deep breath. I firmly escorted OCD Jonathan outside and locked the door, then sat down and thought critically about this technique. As the Samson site described it, you wind on two layers of line in the normal fashion, then drag the line across the drum as it spools, creating two layers of criss-crossed line. Then two more flat layers, then more criss-crossing, until the line is fully spooled. All in an effort to prevent the winch line diving between layers when under a load—which, it seemed on the surface, it might accomplish.

Or would it? Given the instructions to alternate two layers of parallel windings with the crossings, it would still be critical to ensure those parallel layers were tight, or your criss-crossed line would still happily dive between them as it was pressed into the spool when one of the parallel layers above it was pulled tight under a load—perhaps creating an even worse snarl. Additionally, the Samson instructions specified “50 pounds of tension.” That’s not very much—when I respool I employ a minimum of several hundred pounds of tension.

I thought some more. First, I noted that I have never personally had a winch line dive between layers with my “normally” spooled winches, nor have I seen it happen on winches belonging to the far more experienced people I’ve had the luck to train with and learn from. This led me to believe that, except in rare circumstances, the problem was only a problem with poorly spooled lines—i.e. spooled with insufficient tension—and that someone who experienced it because of poor technique and adopted cross-winding as a fix would probably experience it even with cross-winding.

Second, it’s obvious that cross-winding will take up more space on a winch drum than parallel winding, reducing the power of the winch with each unneeded layer, and requiring more line to be pulled off the drum to achieve the same strength. Also, how could you possibly neatly wind two parallel layers atop two cross-wound layers?

There are other issues. In a side-pull scenario, when the criss-cossed layer is uncovered I’d expect the line to jump across the drum with some force, at minimum creating a sharp jerk in what should be a smooth operation. Also I’d expect line speed to increase and decrease as either a crossed line or a parallel line is tensioned.

In the end I remained firmly unconvinced, if not actually calling BS. But was I now an outlier? A dinosaur? I sent the Samson link around to a few friends and associates, including luminaries such as ex-Camel Trophy team members. No one who responded thought cross-winding made sense. Andy Dacey, a director at Wildtrackers in the UK, who not only trains military units in four-wheel-drive techniques but is also a forester and thus extremely familiar with ropes and rope handling, believes the Samson page is aimed at those who spool their winch lines by hand, under very little tension—thus the “50 pound” reference. He also noted that a line under high tension pulled over the line one layer lower at near right angles would put extreme stress on one point, flattening it there. (If you use a synthetic-line-equipped winch frequently, you might notice the lower wraps sometimes look strangely squashed; doing that across the line doesn’t seem like a great idea.)

Andy told me he has no intention of cross-winding his winches. Any of them.

I don’t either.

Now if you’ll excuse me I have to go let OCD Jonathan back in.

He’ll be relieved.

Easy, Jonathan. For illustration purposes only.

Ratcheting screwdrivers, Husky versus Wera

Until last month I’d never bought a ratcheting screwdriver.

Why? I’m not exactly sure. Perhaps I distrusted the mechanism and preferred the extra (assumed) reliability of a standard screwdriver. Perhaps out of a misplaced sense of purity.

In any case, recently I was faced with the fun but monumental task of duplicating, as much as possible, my entire Tucson tool collection for our new place in Fairbanks. Obviously this involved a whole bunch of compromises, since we’re talking about a decades-long accumulation. And it will have to be accomplished incrementally, the most critical tools first. But the cabin needed several important repairs and upgrades, so I had to cover the basics quickly.

Screwdrivers were high on the list. I’d brought a few with me in the cargo trailer in which I hauled our furniture and household goods, but I needed a selection of bits for some weird fasteners I’d found in the cabin. At the Fairbanks Home Depot I found a $20 Husky ratcheting screwdriver with a selection of bits stored in the base of the handle, and decided to try it.

It didn’t take long before I discovered the advantages of the concept. It wasn’t always advantageous, and frequently I left the ratcheting mechanism locked out, but in certain circumstances it made inserting or removing fasteners much faster and more convenient. I was definitely sold on the concept.

However. The Husky tool itself proved problematic. First, the ratcheting mechanism felt coarse, which meant wasted motion turning it back and forth as the excess slack had to be taken up each time—even when it was locked. Much worse, however, was the bit storage, accessed by a ribbed cap in the base. Illogically, the cap was tapered so you pulled on the narrowing butt of the grip, backwards for optimal use. It was so hard to grasp that I took to opening it with my teeth. And it didn’t open smoothly but with a jerk—which meant that half the time it maddeningly spit one or several bits out onto the floor. Do these companies ever conduct beta testing?

Sigh . . . Wondering if there was something better, I did a search, and . . . aha. A German company with which I’m familiar, Wera, made one, model KK 27 RA2. For, naturally, two and a half times what the Chinese-made Husky had cost. Nevertheless, I ordered it. Sadly by the time I did so I was due to leave Alaska for Tucson, so I had it sent south. Thus I have no side by side photos (although thanks to the magic of digital publishing I can edit later).

So, is it two and a half times better than the Husky? Maybe not—the Husky, after all, will do the same job—but it’s satisfyingly way better. The ratcheting mechanism is much smoother and finer, and the bits are held securely in the center of the grip, accessed by a sliding port activated by a button at the end of the grip. Both complaints about the Husky solved—and, in addition, the Wera has a much nicer grip and a stronger magnet to secure the bits. It’s a joy to use, rather than merely okay. The Wera has become the screwdriver I reach for first for many jobs, both household and automotive.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.