Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Toyota (finally) steps up with the new Tacoma*

*Or: Never again will a Toyota factory rep have to say with a straight face, “Drum brakes are better off road!”

Anyone who has read my writing is aware of the huge respect I have for Toyota’s vehicles—a respect gained through long personal experience, from my very first car, a used 1971 Corolla, to the FJ40 I’ve owned for 45 years, to the more-than-several Toyota pickups and Land Cruisers Roseann and I have owned, along with those we’ve driven on several continents.

Those same people also know the very high standards to which I hold Toyota, and my willingness to call out the company when I believe a vehicle it offers for sale does not meet those standards.

No Toyota model has endured more of those call-outs than the previous two generations of the Tacoma. From the model’s laughably archaic rear drum brakes (here) to its open-channel rear frame section (shared with the previous Tundra, here) to high-revving engines unsuitable for truck duty (here), it annoyed me that my company was clearly coasting and cost-cutting, unwilling to invest in improving a vehicle that remained safely on top of the sales charts.

Either someone at Toyota has been reading my stuff (unlikely), or the company noticed that newer trucks such as the Chevrolet Colorado, Ford Ranger, and Nissan Frontier had decidedly surpassed the Tacoma in virtually every area except (arguably) reliability.

Whatever the reason, the 2024 Tacoma is a huge, huge leap.

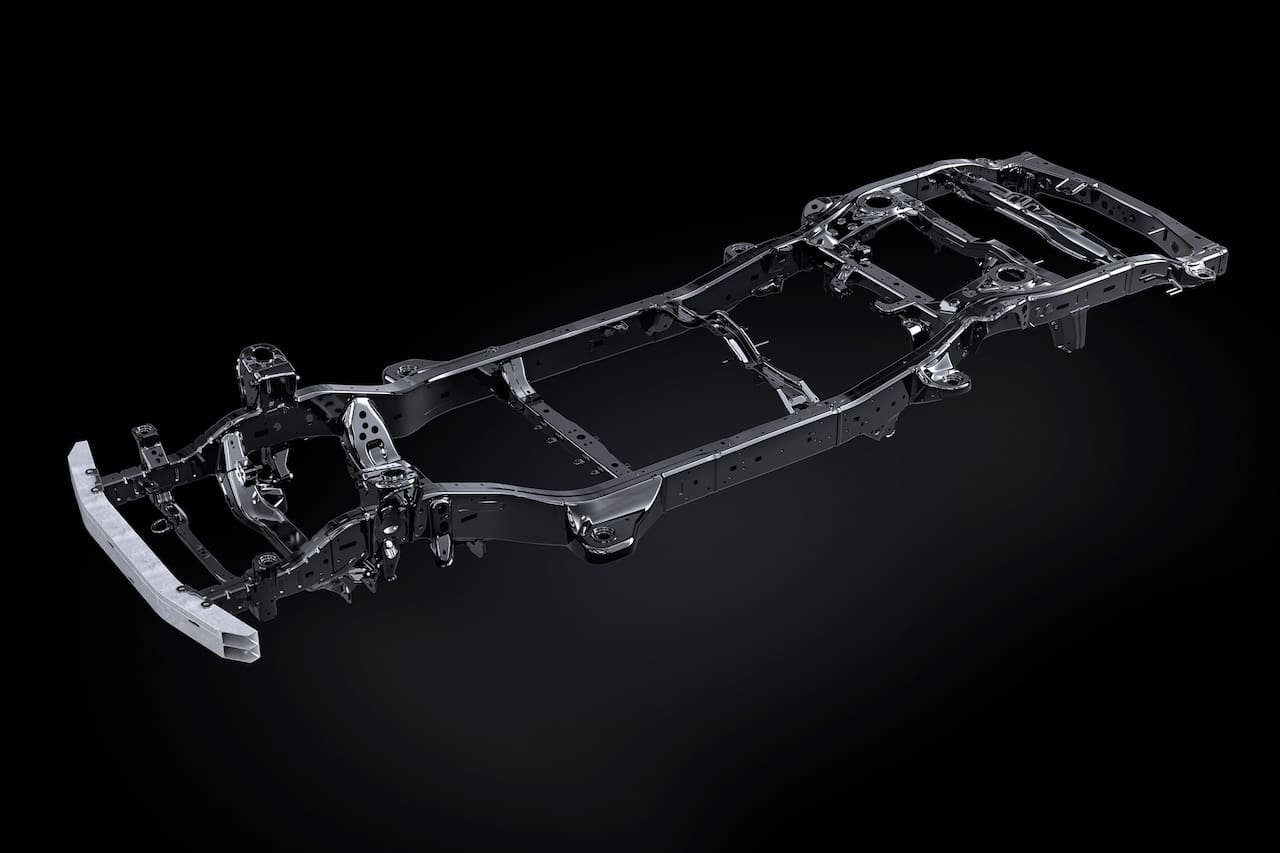

Begin with the chassis, which is now (or rather, once again) of fully boxed construction, far more torsionally and longitudinally rigid than the outgoing platform. It’s a modification of the same chassis that underlies the new Tundra and Sequoia. In addition to the boxed sections, it’s laser-welded from high-strength steel and employs strengthened crossmembers. Bravo.

Next, suspension: While base models (SR, SR5, and the Prerunner) will still employ leaf-spring rear suspension, higher-spec models will benefit from a multi-link coil-spring rear, which will improve ride and handling without sacrificing load-carrying—in fact, load capacity is significantly increased on models such as the new, overlanding-focused Trailhunter. (I’m hoping Toyota learned from the new coil-sprung Tundra, which can exhibit squirrelly behavior under heavy towing loads. This is easy to correct with proper bushing and spring specs.)

Oh, and, yes, all models will sport rear disc brakes. Welcome to the late 20th century, Toyota!

Next: Engines. Remember me bitching about 4,000rpm-plus torque peaks? How about a torque curve that peaks at 1,700 rpm? That’s diesel-like twisting power, and exactly what a truck needs.

The new Tacoma has just one engine configuration: a turbocharged, 2.4-liter inline four-valve four-cylinder. However, differing states of tune, plus the addition of a hybrid drivetrain, result in a spread of horsepower and torque ratings—none of them sub-par, and all with more torque than horsepower. Again—Bravo.

The base SR engine—with an eight-speed automatic transmission replacing the previous six-speed—is a marked improvement over the previous base 2.7-liter engine (159 bhp, 180 lb.ft.@ 3,800 rpm) in horsepower, torque, and where that torque comes in. And take a look at the i-Force Max turbo hybrid, with 326 hp at 6,000 rpm and an astounding 465 lb.ft. of torque at 1,700 rpm, assisted by an electric motor that delivers 48 hp and 184 lb.ft. These were figures I previously only dreamed of having available in the Tacoma. Plus, Toyota gave an approving nod to the few remaining manual-transmission aficionados left in the U.S., with a six-speed clutch-operated option.

What remains to be revealed are a few towing and payload ratings, plus the critical question of fuel economy. However, unlike the previous Tacoma engines, which offered both mediocre horsepower and mediocre fuel economy, at least we know we’ll get the power this time.

Another very pleasant surprise: The dash of the 2024 Tacoma—aside from the ubiquitous, industry-wide giant iPad tacked onto the middle, which I guess I really need to get over—is simple, handsome and functional. In fact I’d put it a close second to my all-time favorite dash layout, that of the current Land Rover Defender. The Tacoma has even incorporated similar all-LED gauges in front of the driver, which should be clearly legible in any light. To repeat myself: Bravo.

Then there’s the external styling. I squinted when I first looked at an actual photo of the new Tacoma, fearing it would ape the design of the new Tundra, which I find . . . how can I put this diplomatically . . . awkward. But no—the Tacoma, especially in the front end, lacks the comically massive, blunt, unharmonious “lines”of the Tundra. The Tacoma is aggressive, but various styling elements combine to break up the whole in to manageable segments. I actually like it, even if I still think our 2000 Tacoma was the best looking era of the model.

Other available niceties? Driver-disconnectable anti-roll bar. ARB-sourced components, including OME suspension. Thirty three-inch tires. Recovery-capable steel rear bumper. The list goes on.

So far I think the new Tacoma is a stunningly bold and much-needed leap for Toyota. It’s enough to make me stop dreaming about the Hilux (well, except for that turbodiesel . . .). The big remaining question is, will Toyota be able to put this all-new model into production and retain the legendary Toyota reliability? The first year of the 2016 update was notable for a higher number of recalls than usual. Only time will tell if the company can hit their marks first time out this time.

In the meantime, as I mentioned: Bravo, Toyota. I am eagerly anticipating a road test as soon as I can arrange it.

Announcing Exploration Quarterly Magazine

We are pleased to announce a forthcoming new magazine, Exploration Quarterly — For those who do not cease to BE CURIOUS . . . to LEARN . . . to EXPLORE . . .

For details, click >HERE<

Knipex parallel-jaw pliers

Despite their occasional usefulness—in some cases serving a purpose no other tool can fill—pliers get little respect in the automotive tool world. Possibly the only tool more scorned is the adjustable (or “monkey”) wrench with its sloppy fit on almost any fastener.

Pliers can at least grip properly; their main drawback is the tendency of the teeth to scar the flats of nuts and bolts, and to slip and subsequently round off fasteners if not gripped tightly enough to risk that scarring.

Enter the Knipex parallel-jaw pliers, or as the company refers to them, pliers wrench.

The lower jaw of the Knipex PJ pliers (my nickname) does not pivot about a central axle; instead it moves straight up and down in a track, and is adjusted with a separate handle on a pivot. The coarse adjustment is accomplished by sliding the handle up or down a toothed track, and the overall range is impressive: The compact 180mm model shown here can adjust its grasp from zero—i.e. gripping a piece of paper or sheet metal—up to a full 1 1/2 inches or 40mm. That means a pair of these could, in a pinch, substitute for a full ratchet/socket and wrench set from 3 or 4mm all the way up to 24mm or so (beyond that their leverage might be insufficient). Add the 250mm model for even more versatility.

One advantage of using the PJ pliers to, say, hold a nut while one unscrews a bolt from it, is that you actually grip the nut, which you cannot do with a standard wrench. This would be extremely useful in tight spaces were dropping the nut might mean a five-minute search in the bowels of the engine compartment—or the mud underneath. Likewise, when trying to thread a nut onto a bolt in a tight space you can retain a firm grip on it. Like all Knipex (pronounced “kineepex,” incidentally) pliers, due to the superior steel used the jaws are quite narrow, further enhancing their usefulness.

Disadvantages? The lack of teeth renders the PJ pliers useless at gripping round things—axles, the shaft of a bolt, etc.—which is why I also carry the company’s excellent standard sliding-jaw pliers. A very useful addition to a home or field tool kit.

Knipex is here.

The longest-lasting trucks . . .

. . . ironically from a Ford truck enthusiasts’ site, even though a Ford doesn’t appear until number five. Full article here.

On the other hand is this investigation into which vehicles (cars, trucks, and SUVs) are most likely to reach 250,000 miles. Here the Ford F350 takes the top spot, followed by no fewer than seven Toyotas among the top twenty. Lots of blanks in the data—engines (diesel versus gas) and time to reach that milestone among them. But interesting.

A better Tacoma . . . finally?

I’ve made no secret of my distaste for the chassis used on the Toyota Tacoma since 2005. In contrast to its predecessor, the first-generation Tacoma—and the Toyota Hilux to this day—it employs an open-channel design under the cargo area. This was followed by a similar design on the 2008 Tundra, hyped as the “Triple-Tech” frame and accompanied by a patently transparent sales pitch assuring consumers how superior it was.

In fact, neither one was at all superior to a fully-boxed chassis. A tube of any cross section, whether round or square, is more torsionally and longitudinally rigid than an open, U-shaped channel of the same weight. Every other Japanese and American pickup on the market now employs a fully boxed chassis in recognition of this—as does the recently re-designed Tundra, in a tacit admission of the nonsense told to us for 13 years.

The retrograde move to an open-channel design made no sense except from an economic standpoint. The only other possibility lies in the rust issues Toyota experienced with some of the first-generation Tacomas, presumably caused by moisture becoming trapped inside the frame. Perhaps the company simply decided to ditch the enclosed section and prevent any possibility of water entrapment, rather than altering the boxed chassis to prevent the issue. (I’ve also read that the problem was simply a bad run of steel and/or poor rust-proofing. I’ve also read that even the open-channel frames have had issues.)

My other big gripe with the Tacoma was the antediluvian drum rear brakes, on the subject of which the company again insulted our intelligence by claiming they were “better off road.” (See here.)

Both these flaws might be rectified soon.

New-vehicle rumors are notoriously unreliable. I remember reading magazine headlines about the “upcoming mid-engined Corvette!” since at least 1972. However, given the recent overhaul of the Tundra, I’m more inclined to give this latest gossip credit. According to several sources, Toyota is preparing to release a redesigned 2024 Tacoma that will feature a fully boxed chassis, four-wheel disc brakes, and possibly even coil rear suspension—all of which feature on the current Tundra. Thus these rumors make sense.

I’ve as yet heard little about engines, and it appears there will be carry-overs in that department. (Stop me before I start whining about current high-rpm, low-torque “truck” engines. Or read this.)

More information as I gather it.

The Guzzle H2O Stream: One purifier to rule them all?

All-in-one, fast purification. (The nifty stainless-steel jerry can is optional.)

Like it or not, the days are long gone when we could go a-wandering, knapsack on our back, and dip our Sierra Club cup into any lake or stream we came to. (And to be frank, the Sierra Club cup was a really lousy design anyway.)

Depending on which studies and statistics you believe, anywhere from 60 to 80 percent of the surface water—lakes and streams—in the U.S. is significantly contaminated with something not good for you, from E. coli to mercury. There are probably a few creeks at 12,000-feet-plus in the Rockies that are still as pure as God intended them, but everywhere else you’d be wise to ensure the water you use from natural sources has been purified, or at least filtered.

What’s the difference? In general, a filter is designed to remove such waterborne pathogens as protozoa (e.g., Giardia and Cryptosporidium) and bacteria (e.g., Salmonella and E. coli). A purifier will kill these organisms as well as viruses. Until recently, consumer-grade water filters could not block the passage of viruses, which average just .02 microns in diameter compared to the relatively huge size of bacteria (.2 to 1 micron) and protozoa (2 to 50 microns). The historically accepted methods for killing viruses included exposure to UV light, treatment with iodine, and boiling. Today several companies produce filters capable of blocking viruses, so the distinction has become somewhat blurred.

Do you need a purifier? At this time, for travel in North America, probably not, as viral contamination of surface water is relatively rare here (potential exceptions include, for example, lakeshores with heavy human activity). However, if your plans include exploration of developing-world countries, it’s definitely worth considering, as viral pathogens such as hepatitis A and E, norovirus, adenovirus, and enteroviruses, among others, might be present. And, after all, there’s no such thing as water that’s too pure.

There are dozens of filters on the market—including those capable of blocking viruses—suitable for backpackers and canoeists, who might need no more than a gallon or two per day. The MSR Guardian Purifier (the pump version) is one such. For overland travelers who have bulk water tanks in their vehicles, and who use that water for washing dishes and perhaps showering, and who thus might go through three, four, or more gallons per day per person, the work and time involved in hand-pumping a liter or two per minute would get old really fast.

One leisurely but effective solution is MSR’s Guardian Gravity purifier, which comprises a gravity-fed filter capable of eliminating viruses (NSF P248 standard), fed by a 10-liter hanging bag. The system produces only about a half-liter per minute (and it must be cleared of silt and debris in advance), but if you’re in camp for a few hours you can easily produce 20 or 30 liters of pure water. Of course you need to set a timer or keep an eye on the unit to know when to refill, and topping it up more frequently helps push water through the filter (slightly) more quickly. But otherwise it’s completely passive.

Want something faster than that? I’ve recently been using what might be the best high-output water-purification system I’ve ever tried.

The Stream from Guzzle H20 (Okay, I would have picked a different company name) comprises, in a compact Pelican-like case about ten by twelve by eight inches, a primary, easily replaced .5-micron carbon-block filter, a 12V pump powered by an LiFePO4 battery, and a transparent capsule incorporating an LED UV-C light source. The carbon-block filter removes chlorine taste and odor, and reduces or eliminates NSF 41 contaminants, VOCs (volatile organic compounds) lead, and mercury. The UV-C light inactivates protozoa, bacteria, and viruses with 99.99-percent efficiency, according to third-party testing. And the Stream produces an astounding .75 gallons per minute in pumping mode, or 1.1 gpm with a pressurized source such as a municipal tap. The LiFePO4 power source will process 32 gallons on a single charge in pumping mode.

What this means is that the Stream could completely refill our Land Cruiser Troop Carrier’s 29-gallon tankage (24-gallon chassis tank plus jerry can) with purified water on a single charge and in about 38 minutes—significantly less if sourced from a municipal tap. No other system I know of comes close.

Using the Stream couldn’t be simpler. The inlet hose plugs into a quick disconnect fitting on one side of the case; the outlet hose into a similar fitting on the other side. The inlet is color-coded red (in fact the entire hose is red); the outlet blue to avoid confusion. Stick the 1-micron pre-filter of the inlet hose into the source, hold the outlet hose over your container, and hit the switch. You’ll be surprised at the rate of flow—the thing fills a standard water glass in a few seconds.

I opted for the “Overland bundle,” which includes an extra carbon-block filter and a 30-foot outlet hose, so you don’t have to park right next to a source if you have built-in tanks in your vehicle. I also got the significantly larger “Guide” prefilter to clear up the murkiest swamp water.

With this setup I would have felt completely comfortable exploiting natural or municipal water sources anywhere I have traveled on any continent. I was impressed with the thought behind the system, the quality of the components and assembly, and the speed—and taste—of the output.

As you might imagine, the Stream is a significant investment. The standard model is $1,195; the Overland bundle is $1,288, and the Guide prefilter is $65. However, given that safe drinking water is arguably the number one concern on any trip, you might consider it a bargain. I do.

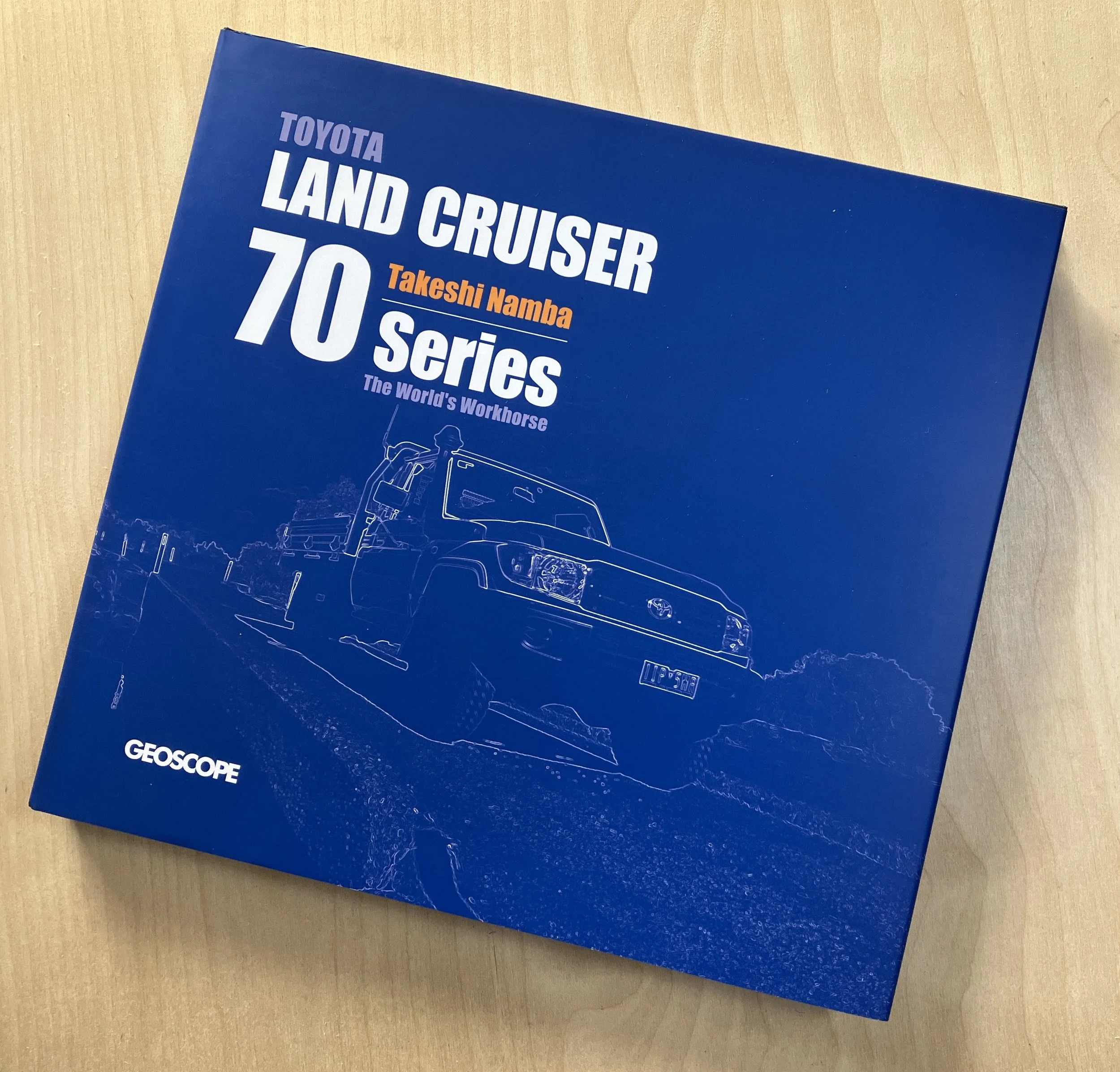

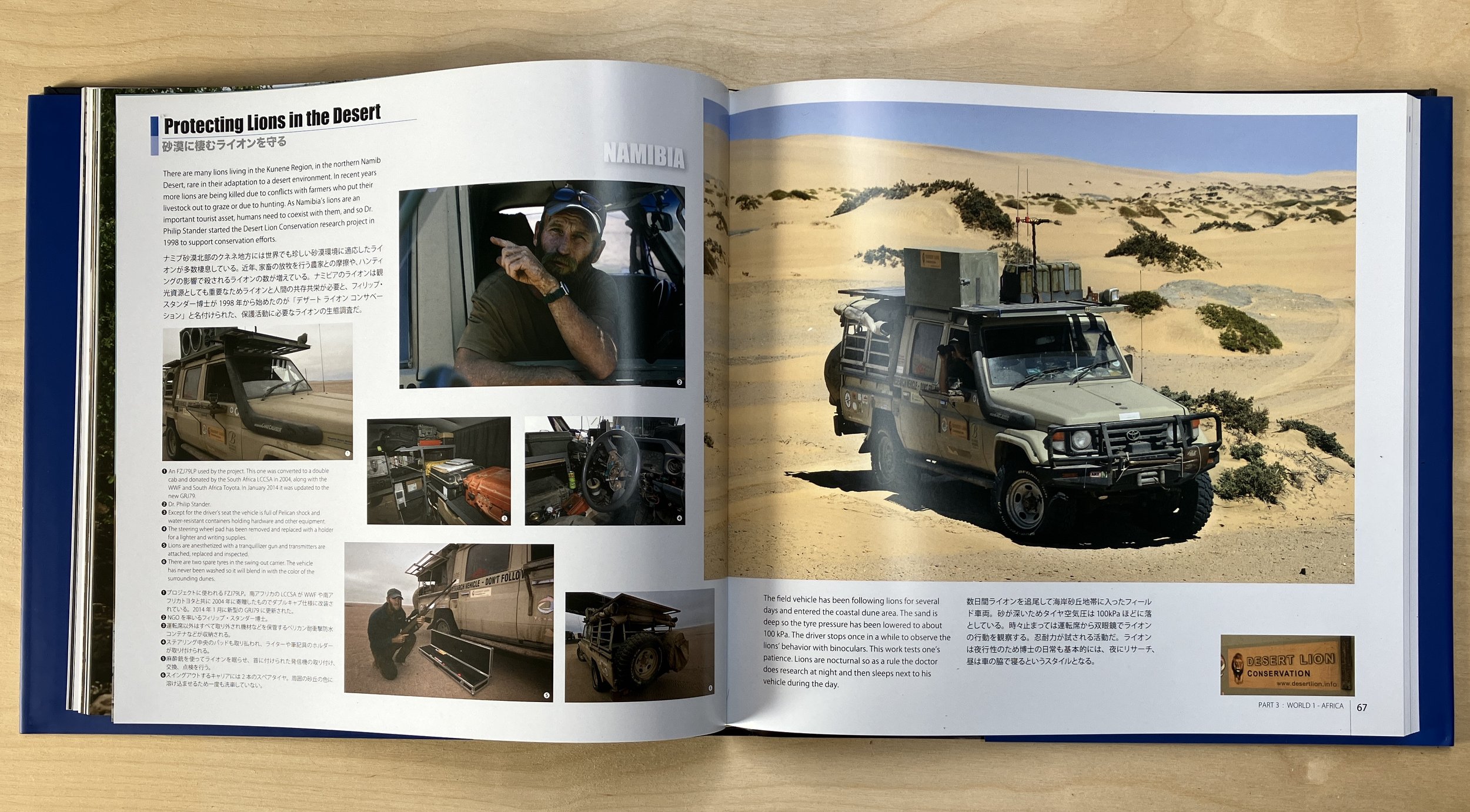

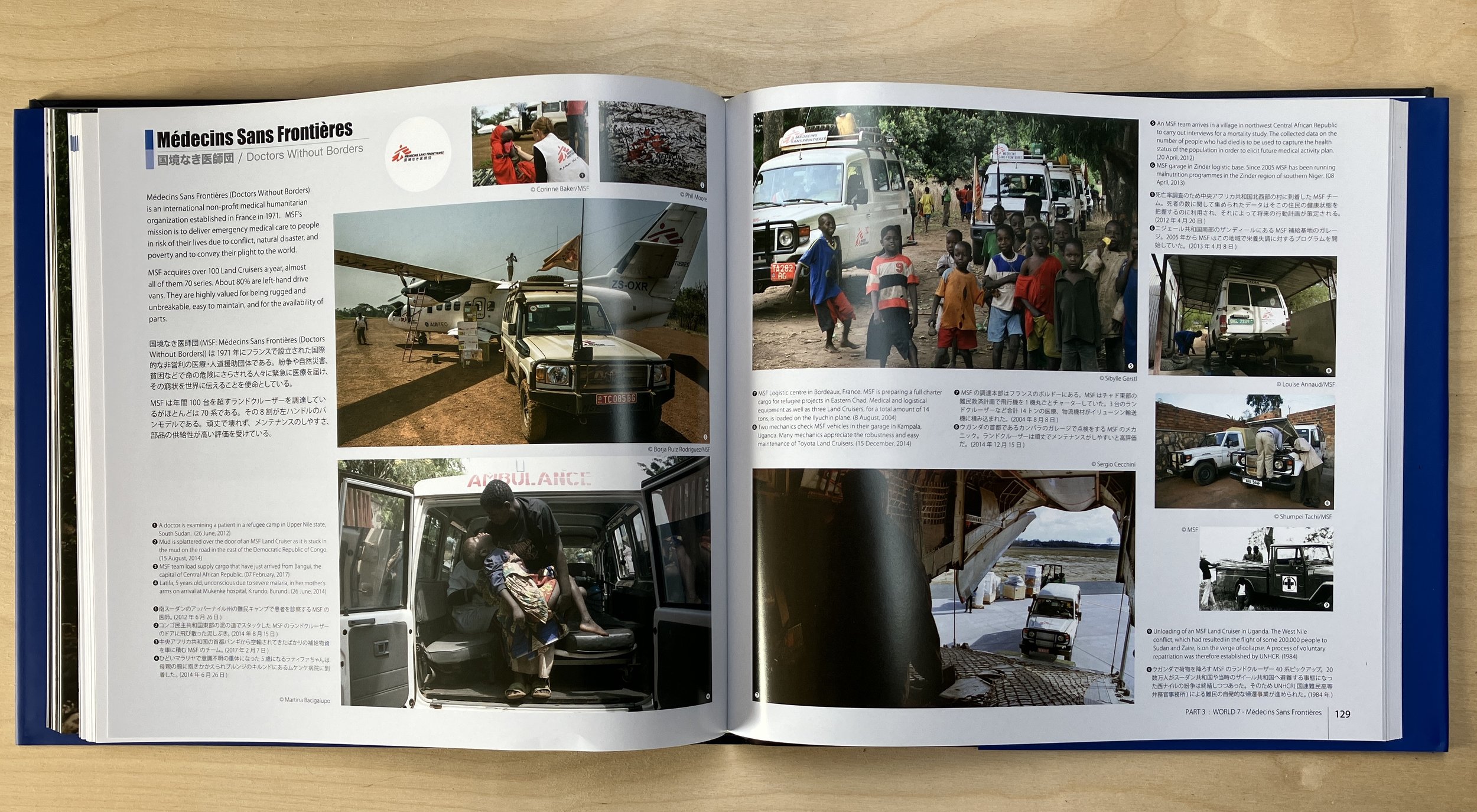

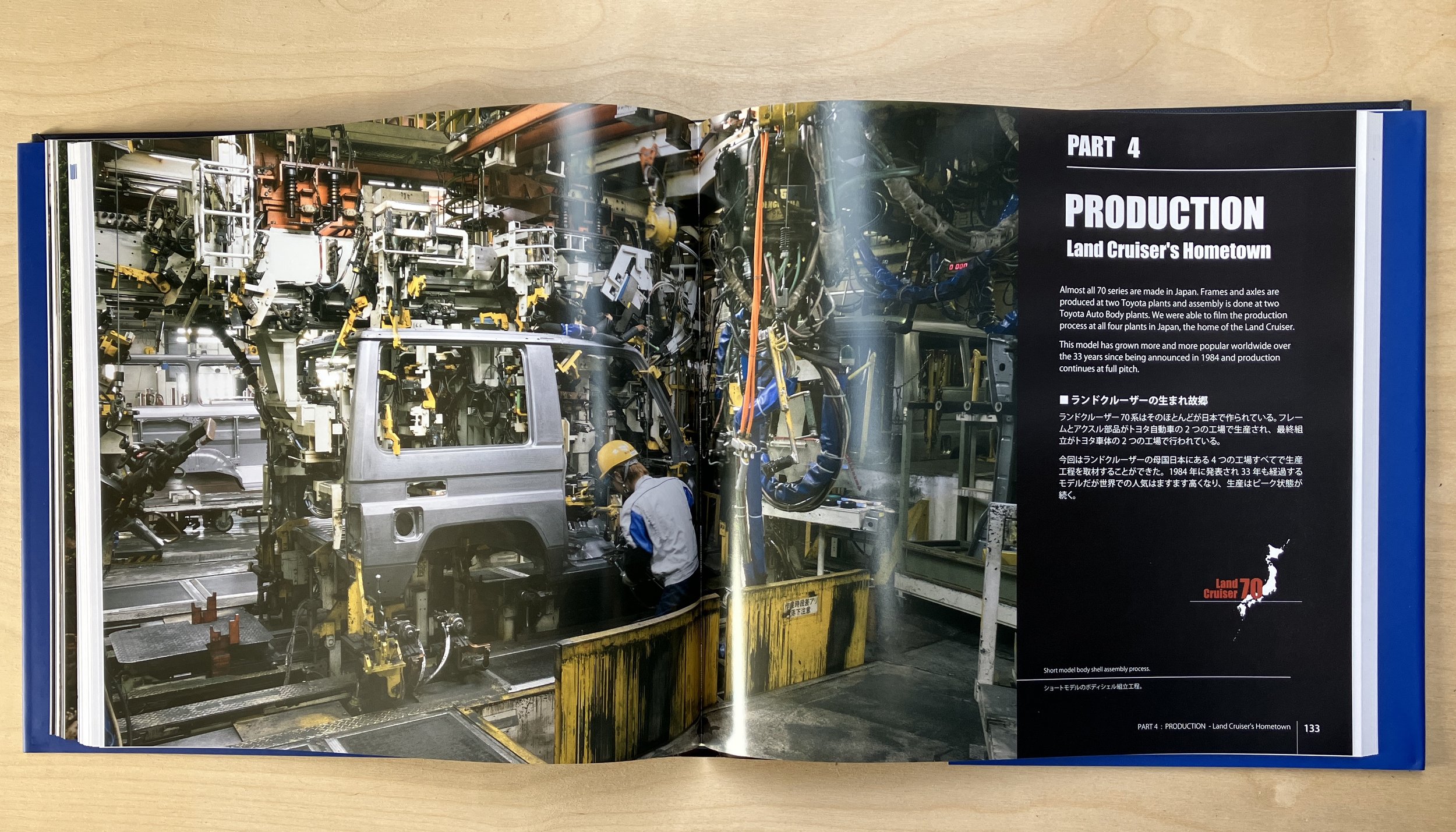

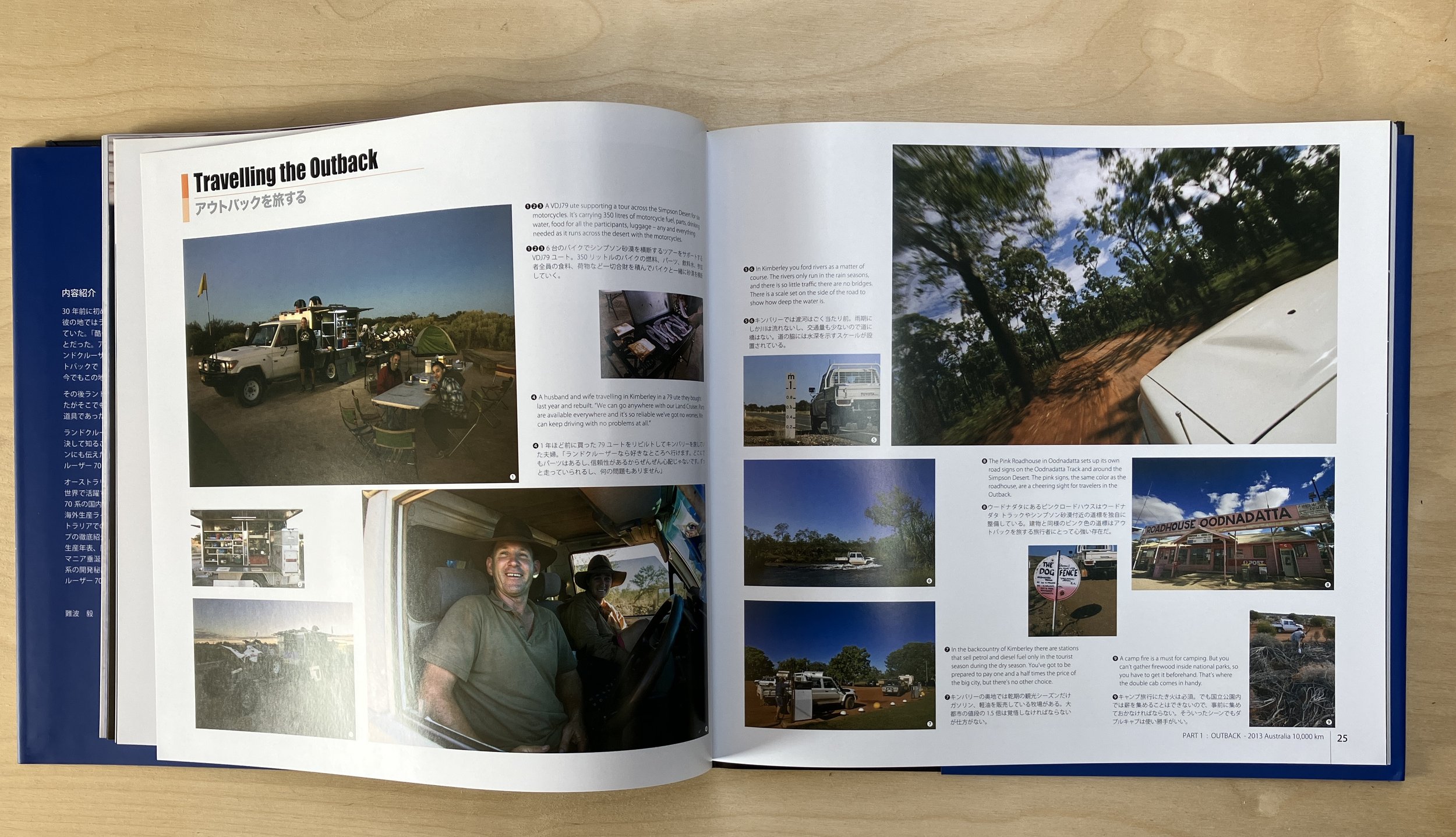

70-Series Land Cruiser book

If you’re a 70-Series Land Cruiser owner—or hopeful future owner, or even just an aficionado—this book is a valuable and enjoyable reference. It comprises over 200 coffee-table-sized pages of crisply produced photographs—well over a thousand in aggregate—along with the history of the series, a complete tour of the factory, and accounts of use of the vehicle all over the globe.

The text is in Japanese and (excellent) English. There are numerous graphs in the back of production history and model changes, plus schematics of all known chassis and body variations. I’m very glad I got a copy.

The link to order is here.

At last, a small shipment of the digitally printed VDEG

There are scant few books that are universally recognized as the timeless bibles in their respective fields: Adlard Coles’s Heavy Weather Sailing; Jack O’Connor’s The Rifle Book; Julia Child’s The Art of French Cooking, Olaus Murie’s A Field Guide to Animal Tracks, to name a few.

Tom Sheppard’s Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide belongs firmly in that category.

I feel free to say this even though I have been its co-author since 2016, because the VDEG’s reputation was established long before my contributions—in 1998, when Tom Sheppard published the first, hardbound edition in conjunction with Land Rover.

I’d been devouring Tom’s articles on his Sahara explorations for several years by then, and when I read about the just-released book I drove 120 miles to Scottsdale, Arizona, to the Range Rover dealership there—the only outlet in the state—and stood in line at the counter behind a woman who had just bought a Range Rover and was agonizing over the choice of some rhino or leopard-themed accessory. I took my copy home and read it cover to cover.

Soon thereafter, Tom took over the publishing, after which the contents no longer leaned nearly exclusively toward Land Rovers and the relevance of the book expanded hugely.

In 2010, after corresponding with Tom through my position as editor of Overland Journal, Roseann and I met him at his home north of London. In sharp contrast to the brash personality one would expect of an ex-RAF test pilot and RGS Ness Award recipient, we found a charming, self-deprecating man who loved sitting in his upstairs office watching sheep graze in the field below as much as he did exploring Algeria solo and completely off-tracks. We became friends, and in 2015 I was gobsmacked to be asked to share to cover of VDEG.

We maintain a regular, lively correspondence which continues to inspire me to want to be Tom Sheppard when I grow up. He recently sent photos of the new driving lamps he’d just installed on his BMW motorcycle, the better to be able to blast around the back roads near Hitchin.

Tom’s next birthday, by the way, will be his 90th.

To the book: If you have a copy, you are already familiar with the stupendous depth of its information, spread over 620 pages—four-plus pounds worth. Unlike many of the bibles listed above, VDEG receives continual updates with each printing, even if minor. Thus information on vehicles, drivetrains, international shipping, communications, and navigation are always up to the minute in accuracy and relevance. Whether you’re planning a week-long exploration of your own state, or have been tasked with leading a multi-vehicle scientific expedition across the Sahara, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide contains the knowledge you need.

If you don’t own a copy, you should. If you already do, and it’s a post-2016 (Edition 4) version with the new guy on the cover, you’ll find mostly updates to existing information. The big change since then came with Edition 5, which transitioned to sharp, all-digital printing and a larger, easier-to-read (and heavier!) format. It’s a worthy upgrade. The print runs, however, are small—we have just 90 copies and no word whether there will be further ones. I should have said 89 copies, because I’m saving one for myself . . .

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.