Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Special report: Adventure Overland UK Show

Those of us in the U.S. overlanding world have always assumed that our English counterparts were well ahead of us. They invented the Land Rover, after all (not to mention those awesome MOD water cans with the little brass chains to secure the cap and breather). And they can take the Chunnel to Calais, turn right, and be in Morocco in about 24 hours, or continue straight on to the Silk Road. Plus, South Africa—which was of course a British colony for ages—is the source for much of the premier overlanding equipment on the market, from such stellar names as Howling Moon, Front Runner, Eezi-Awn, National Luna, and a host of others.

It seems, though, that while the English did get a head start on us Yanks in terms of access to proper equipment, their overland community has until now lacked any sort of real cohesion. Four-wheel-drive shows have tended to focus on hard-core abandoned-quarry rigs, the corollary to rock-crawlers here. The venerable Horizons Unlimited meets were dominated by motorcycles.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the Overland Expo—which will celebrate its fifth anniversary in 2013—has brought together an extended overlanding family that now views each year as much a reunion and a chance to catch up on each other’s news as an educational and product show. (And our number one source of foreign attendees? Great Britain, of course.)

That’s at least partly why Tom McGuigan, who owns Off Road UK and has promoted several other vehicle-related shows in Great Britain, decided to put together the Adventure Overland Show, an overland-specific event in Daventry, a few hours northwest of London. He generously invited Roseann and me to attend, and put us up in a tent at least as big as our cottage at home—it could have effortlessly doubled as a garage for one of the dozens of nearby Defenders. [And Tom's partner Shiela made sure we had extra comforters and pillows against the cold—much appreciated.]

[SEE OUR COMPLETE PHOTO SET ON OUR FLICKR ACCOUNT, CLICK HERE.]

We felt right at home situated between Overland Expo regulars Austin Vince and Lois Pryce on one side and Toby Savage on the other. Just behind us was Jens of Wohnkabinencentr.de, who is importing Four Wheel Campers into Europe, modified slightly in interior decor and names (the Wildcat is the Fleet in North America).

Not far away was another friend and Expo alumnus, Chris Scott, who’d borrowed a car to bring boxes of his latest Overlander’s Handbook, samples of which were laid out on—could that really be?—yes, an ironing board wrapped in a bit of colorful cloth. Chris, we know you’re skint, but . . .

If what we saw in this first event is any indication, the Adventure Overland Show has a bright future. There were dozens of vehicles set up for long-distance travel, vendors of equipment (including those MOD water cans—tragically no room in our Kenya-bound luggage), tour companies (including Transylvania Tours, whose logo is—what else—a smiling cartoon Bella Lugosi with fangs), and, set off in a corner, a booth for the Parrot Rescue Association (no idea, but a worthy endeavor). One delightfully British genre is the bushcraft community; there were several vendors of volcano kettles and proper scandi-grind knives, and a spot where kids of any age could learn how to use flint (well, okay, magnesium) and steel to start a fire.

Much on offer at the Adventure Overland Show was identical to what we see at the Overland Expo, happy confirmation that dedicated overlanding equipment has made a nearly complete transition to U.S. suppliers—in fact I’d venture to say we might just be edging ahead in terms of variety. But there was some interesting exotic kit. Did I mention the MOD water cans? Right.

Long-distance travelers wanting a compact home on a Land Rover chassis could look at the L’Azalai campers. Built of a 20-millimeter-thick composite, the L’azalai fits either the 110 or 130 Defenders, and incorporates a complete galley with sink, stove, and fridge, a dinette, a hanging closet, and a large bed. Since it’s chassis-mounted, there’s even a (tight) pass-through into the cab. The L’Azalai just manages to avoid the Queen Alien look of so many add-on campers; especially on the 130 chassis.

David Bowyer of Goodwinch claims to have taken the Chinese-manufactured winch to a higher level, with better waterproofing, stronger motors, and cone brakes that eliminate the overheated line that can be caused by a drum brake. He’s one of the few—no, strike that, he’s the only winch importer I’ve seen happy to display the internals of his Asian-made winches.

If I had to pick a favorite product at the Adventure Overland Show, it would be the Cap Lander camper made for Defenders and Japanese pickups. Constructed of a honeycomb composite that’s not only light and rigid, but also insulative and partially translucent to brighten the interior, the slide-in unit comprises an astonishingly space-efficient portable home—bed, sink, shower, stove, porta-potti, etc.—in a 600-pound package. Look for a more in-depth review of the Cap Lander soon in Overland Tech and Travel.

[SEE OUR COMPLETE PHOTO SET ON OUR FLICKR ACCOUNT, CLICK HERE.]

Overall, Tom McGuigan did a wonderful job bringing together the British overland community in this first event. We wish him all the best in the future, and we look foward to being at the Adventure Overland Show 2013 in an even greater capacity.

[We also just heard from Iain Harper that HUBBUK will be hosting an expanded show in late May 2013 in Leicestershire, incorporating more 4x4 overlanding as well—great to hear!]

Land Cruisers of Baharia, Egypt

Land Cruisers of Baharia, Egypt—a set on Flickr

Land Cruisers of Baharia, Egypt—a set on Flickr

The oasis of Baharia, about five hours south of Cairo, is the gateway to the Western Deserts and a major hub for expedition services and vehicles.

On our way there during the Sykes-MacDougal Centennial Expedition in February 2012, we heard there was a booming trade in all things Land Cruisers, but we were not prepared for the sheer numbers of every year and model.

There were plenty of new, expensive examples, but there were many custom amalgamations that sometimes boggled the mind. Apparently, to avoid the high import duties on any vehicle (new or used), canny Egyptian mechanics in Baharia started bringing in cut-up halves and quarters of Land Cruisers from neighboring countries, and then welding them back together after arrival—voila, a duty-free Land Cruiser.

These photos were taken in just one day plus part of a morning, not even a full 8 hours in the town during daylight. There were hundreds—literally half the vehicles in town were Land Cruisers. Almost all the images are snapshots, taken out the window as we drove or shot quickly while walking. I included a couple of interesting non-Toyota shots.

Field repair? Why not a field upgrade?

A few days ago my friend Bruce stopped by our place on his impeccably prepared Suzuki DR650 while out on a day ride through the desert. While we had lunch, he turned off the fuel petcock to the DR650's single carburetor—standard procedure on a carb-equipped bike. When he turned the fuel back on, the six-inch length of fuel line ruptured with an audible pop. It appeared the black plastic fuel tank was not venting properly and had built up internal pressure sitting in the sun. When the pressure was released into the fuel line it gave way.

Bruce was prepared. Not only did he have a spare length of fuel line with him, it was the superior type with a braided fabric sheath, which helps protect the line from damage and UV exposure (augmenting the nice wire wrap supplied by the factory), and looks better to boot. In five minutes we had repaired the break and given the Suzuki an upgrade. The only remaining to-do item when Bruce got home was to replace the slightly oversize hose clamps from the spares kit.

Function and elegance: Billingham camera bags

Handsome, durable, and cavernous: the Billingham 550Carrying photo equipment on safari presents a conundrum. It’s critical that camera bodies and lenses be protected from dust, moisture, and impacts. Yet everything must be quickly accessible and organized in such a way as to allow fast identification.

Handsome, durable, and cavernous: the Billingham 550Carrying photo equipment on safari presents a conundrum. It’s critical that camera bodies and lenses be protected from dust, moisture, and impacts. Yet everything must be quickly accessible and organized in such a way as to allow fast identification.

Over the course of 20 years of photojournalism and hundreds of equipment reviews, I’ve used at least a dozen camera bags and carrying systems extensively, and a couple dozen more for long enough to become familiar with them. Without doubt the most bombproof was the Lowepro Omni Pro Extreme I still own—a padded, suitcase-shaped, compartmented nylon bag with a panel flap that opens the entire contents to view, and which fits inside a completely water- and dustproof Pelican 1520 case. It received its ultimate test in Zambia, on a game drive in an open Land Rover when our guide was trying to get ahead of a huge herd of cape buffalo. I was in the middle seat; the case was on the rear seat next to a fellow journalist who, in an unfathomable act of mindlessness, balanced it on the rear rail of the moving vehicle while he changed positions. The first I became aware of what he’d done was when I heard him say, “Oh,” and turned in time to see the Pelican case hit the ground on a corner and bounce like a 14-year-old Russian gymnast, then cartwheel three or four times into a large pile of herbivore dung.

Bombproof, but heavy and low on convenience: The Lowepro Omni Pro Extreme Nothing inside was even jostled—and I doubt any other camera case I’ve ever used could have accomplished the same feat. The problem with the Omni Pro system is access: From fully closed (which mine fortunately was when it took the header) to fully open requires unsnapping the Pelican latches and opening the lid, unsnapping the soft case’s handle, undoing two Fastex buckles, then unzipping the case and grabbing a camera to photograph the elephant which has since abandoned its bluff charge, gone back to browsing, and fallen asleep. The full system is also very heavy for its volume—and that volume is restricted absolutely to the dimensions of the hard case. Two SLR bodies, a flash, and three lenses pretty much max it out. You can carry the Omni Pro without the Pelican, briefcase-like, but it bulges oddly with the weight of the contents, and the proud “Lowepro” logo has the same number of letters as “Steal me.” (What I’d give for a camera bag with a big fat embroidered label reading something like, “URINE SAMPLES— KEEP UPRIGHT”)

Bombproof, but heavy and low on convenience: The Lowepro Omni Pro Extreme Nothing inside was even jostled—and I doubt any other camera case I’ve ever used could have accomplished the same feat. The problem with the Omni Pro system is access: From fully closed (which mine fortunately was when it took the header) to fully open requires unsnapping the Pelican latches and opening the lid, unsnapping the soft case’s handle, undoing two Fastex buckles, then unzipping the case and grabbing a camera to photograph the elephant which has since abandoned its bluff charge, gone back to browsing, and fallen asleep. The full system is also very heavy for its volume—and that volume is restricted absolutely to the dimensions of the hard case. Two SLR bodies, a flash, and three lenses pretty much max it out. You can carry the Omni Pro without the Pelican, briefcase-like, but it bulges oddly with the weight of the contents, and the proud “Lowepro” logo has the same number of letters as “Steal me.” (What I’d give for a camera bag with a big fat embroidered label reading something like, “URINE SAMPLES— KEEP UPRIGHT”)

My least favorite camera bag is ironically one of the most iconic: the Domke F2, beloved of grizzled chainsmoking photojournalists (even, inexplicably, my wife Roseann, although she isn’t grizzled and doesn’t smoke). Constructed of undeniably stout and good-looking canvas, the Domke offers zero impact protection for the contents and next-to-zero protection from dust. The spring-steel clips that hold the lid closed must be manipulated with two hands if you need them open in a hurry, and side-pocket flaps gap wide enough to eject batteries if the bag is tipped. Perhaps the F2 works for covering the Academy Awards (“Look this way Ms. Watts!”) or climate-change conventions in Zern, but in the field it’s a dead loss, for me at least.

Domke: Fine if your preferred photo subject is Naomi Watts. For several years now I’ve used a Mountainsmith Endeavor (first a prototype, then a production version), and I’ve been highly impressed with its utility, physics-defying interior space (in bright yellow for visual contrast), decent padding, and excellent dust protection. A sleeve on the back slides over the extended handle of a rolling carry-on bag, and the shoulder strap is sufficiently padded for long carries. The Endeavor even endeavors to be socially responsible: Its sturdy Cordura-like fabric is made from recycled PET bottles. At $140 it’s a bargain. I still recommend it, and the company makes several variations on the theme.

Domke: Fine if your preferred photo subject is Naomi Watts. For several years now I’ve used a Mountainsmith Endeavor (first a prototype, then a production version), and I’ve been highly impressed with its utility, physics-defying interior space (in bright yellow for visual contrast), decent padding, and excellent dust protection. A sleeve on the back slides over the extended handle of a rolling carry-on bag, and the shoulder strap is sufficiently padded for long carries. The Endeavor even endeavors to be socially responsible: Its sturdy Cordura-like fabric is made from recycled PET bottles. At $140 it’s a bargain. I still recommend it, and the company makes several variations on the theme.

Tough and versatile: The Mountainsmith Endeavor Only a couple of things made me want more. First, I wasn’t enamored of the black, rather high-tech appearance of the bag, especially compared to the organic look of the Domke. That was a purely personal issue; another was purely geographic: We spend a lot of time in East Africa, some of it in tsetse fly country—and tsetses are attracted to black (and blue). Time after time, I’d be driving through miombo woodlands, dressed properly in non-tseste-attracting khaki, and would look down to see the Mountainsmith bag being used as an aircraft carrier by a half-dozen or more of the little bastards. (A recent study suggests that blue and black initiate a strong landing response in tsetses because those are the colors of the shadowed areas of foliage where they hide.) Finally, even the Endeavor couldn’t hold all my equipment, and it was the antithesis of the accessibility already mentioned to have gear divided between two bags.

Tough and versatile: The Mountainsmith Endeavor Only a couple of things made me want more. First, I wasn’t enamored of the black, rather high-tech appearance of the bag, especially compared to the organic look of the Domke. That was a purely personal issue; another was purely geographic: We spend a lot of time in East Africa, some of it in tsetse fly country—and tsetses are attracted to black (and blue). Time after time, I’d be driving through miombo woodlands, dressed properly in non-tseste-attracting khaki, and would look down to see the Mountainsmith bag being used as an aircraft carrier by a half-dozen or more of the little bastards. (A recent study suggests that blue and black initiate a strong landing response in tsetses because those are the colors of the shadowed areas of foliage where they hide.) Finally, even the Endeavor couldn’t hold all my equipment, and it was the antithesis of the accessibility already mentioned to have gear divided between two bags.

In the meantime, years and years ago (like, in the days of film . . . ) I had met a photographer who used only a pair of superb Leica M6 rangefinder cameras for his work. Three lenses—a 28mm, a 50mm, and a 135mm, if memory serves—comprised his entire professional suite. He carried the lot in an exquisite bag of khaki twill woven so densely it had a silk-like sheen, and set off with leather trim and brass hardware. “It’s a Billingham, from England,” he said when I asked. I immediately downloaded . . . no, wait—I called and had a catalog mailed to me. Martin Billingham, it turned out, began making bags for fishermen in 1973, then a few years later discovered that photographers in New York had adopted them to carry Rolleis instead of reels. A keen photographer himself, he embarked on a tentative change in direction, which proved so successful that production soon shifted entirely to the photographic market. The business is still family-owned, and all manufacturing remains in England in a factory in Brierley Hill, just outside of Birmingham.

Billingham’s flagship bag, the 550, caught my imagination—as did its price, far beyond my means at the time. Reluctantly, I filed the catalog away (in the same drawer as the Leica M6 brochure . . . ). But a couple of years ago, while planning a trip to Kenya, the Billingham wormed it way into my thoughts again, and I realized that I had three or four other nearly new camera bags I no longer used. A quick flurry of eBay activity and I was close enough to spring for the balance. I took a deep breath and clicked “Buy now” on the B&H site.

There’s always a danger in fulfilling a long-held dream, whether it be buying a high-end product, meeting someone you’ve admired from afar, or journeying to a place you’ve read about since childhood. In our minds such experiences are always perfect; fantasies never include downsides. Fortunately Martin Billingham did not disappoint.

Perfect in every detail. The material on the 550 was just as I remembered, so tightly woven it’s classified as fully waterproof, and astonishingly resistant to grime and stains—in fact I’ve been having a hard time giving this bag the patina it deserves. (By comparison the canvas on the Domke looks like sack cloth.) The top flap covers a lengthwise zipper, so contents in the main compartment are well-protected yet accessible in seconds. In a vehicle I leave the flap unbuckled so all I have to do is flip it out of the way and slide the zipper to pull out a clean camera. Inside that main compartment I have at present one 5D and one 5D MkII body, a 24-105L zoom, a 17-40L zoom, a 70-200L F4 zoom, a 300L F4, a 1.4 converter, a 15mm Canon fisheye, a Tamron 90mm macro, and two EX flash units. Outside pockets—two large and flapped, two small and zippered, and a big flat zippered one on the back—hold all those things so necessary to modern digital imagery: spare lithium-ion batteries and chargers, a sensor-cleaning kit, a data-transfer device, and spare CF cards in their own case. Synch cords, the 240-page manual to remind me how to access half the functions on the 5D MkII . . . on and on. Should I need even more space, the 550 comes with two flapped end pockets that attach or come off as necessary.

Perfect in every detail. The material on the 550 was just as I remembered, so tightly woven it’s classified as fully waterproof, and astonishingly resistant to grime and stains—in fact I’ve been having a hard time giving this bag the patina it deserves. (By comparison the canvas on the Domke looks like sack cloth.) The top flap covers a lengthwise zipper, so contents in the main compartment are well-protected yet accessible in seconds. In a vehicle I leave the flap unbuckled so all I have to do is flip it out of the way and slide the zipper to pull out a clean camera. Inside that main compartment I have at present one 5D and one 5D MkII body, a 24-105L zoom, a 17-40L zoom, a 70-200L F4 zoom, a 300L F4, a 1.4 converter, a 15mm Canon fisheye, a Tamron 90mm macro, and two EX flash units. Outside pockets—two large and flapped, two small and zippered, and a big flat zippered one on the back—hold all those things so necessary to modern digital imagery: spare lithium-ion batteries and chargers, a sensor-cleaning kit, a data-transfer device, and spare CF cards in their own case. Synch cords, the 240-page manual to remind me how to access half the functions on the 5D MkII . . . on and on. Should I need even more space, the 550 comes with two flapped end pockets that attach or come off as necessary.

Is the Billingham 550 perfect? No. For example, the flaps of the exterior pockets, while superior to those on the Domke bag, still fit too loosely for my comfort, and the snaps are impossible to close with one hand unless there’s something bulky inside to press against. I wish there were a zippered closure under each flap; that way you could keep the zip closed for security during transport, or leave just the flap snapped for quick access while shooting. Also, while the shoulder strap is comfortable and strongly attached, picking up the full bag (mine weighs 25 pounds all up) by the carrying handle makes me very nervous, as it’s secured only by two thin leather straps and buckles. And a final nitpick: A pretty leather luggage tag is optional. C’mon, Martin—for $500 I think you could throw that in. In a futile gesture of protest I transferred an old black Lowepro luggage tag to my 550. Sadly, it looks rather naff, so I’ll probably succumb and order the correct one. After all, from the looks of things this bag will be with me for a long time.

The Billingham range starts with the 550 and goes all the way down to a single pouch with a belt loop, perfect for a point-and-shoot. And yes, they still make a bag specifically designed for the Leica (digital) rangefinder system.

Some day . . .

The Cinch to Hang, or Why didn't I think of that?

How many times have you been camping amongst trees and wanted to hang something on one of them—a kitchen utensil roll, a bathroom kit, a shaving mirror, a jacket or hat—and wished there were a nice stub of a branch right . . . there? Just hammering in a nail is considered impolite to the tree these days.

Charles Ay’s solution was clever enough to win two U.S. patents. The Cinch to Hang is a two-ounce plastic device that, when attached to any tree up to three feet in diameter with the included strap, can hold up to 50 pounds on its fold-out hook.

I subjected a sample to a comprehensive evaluation—which took about, oh, five minutes including installing it on the tree. Very simply, it works as advertised. There was no slippage at all with light loads, and the device only migrated down an inch or two even when I grabbed the hook and exerted significant downward force. Hanging something like a full day pack would be no problem. A pair on a pair of trees would comprise a perfect mount for a clothes line. One strapped to a slanting overhead limb would make an ideal lantern hanger.

The standard Cinch to Hang kit ($24.95) comes with four hooks and a single strap, but the slot on the hook is one inch wide so it would take any equivalent strap if you want to hang them on different trees. The company’s website is a placeholder (with a photo of the wood prototype) for another week or so, but you can order by email. It’s one of those rare products you’ll truly wonder how you did without. Obviously the Patent Office thought so.

The one-case tool kit, part 1

It would be pretty easy to bring along all the tools you’re likely to need on even an extended overlanding trip, covering virtually any repair not involving a new long block. What’s that? Oh—you also want room for, like, food? And maybe a tent and sleeping bags? Hmm . . . now that’s a problem.

The size of tool kit you carry (or should carry) is subject to a bunch of variables. The length of the trip and the remoteness of the route are two obvious considerations. The age of the vehicle is certainly a factor—even reliable vehicles need more attention as they get older. If you can just go out and write a check for a new Land Cruiser every time you leave on a major trip, your need for tools should be minimal. On the other hand there are people like, well, Roseann and me. A brief survey and some arithmetic established that the average age of all the four- and two-wheeled vehicles currently in our fleet—1970 Triumph Trophy, 1973 FJ40, 1974 Series III 88, 1981 BMW R80 G/S, 1982 Porsche 911SC, 1985 Mercedes 300D, and a practically spanking-new 1987 Honda NX250—is 33 years. All solid vehicles, but inevitably in need of attention now and then, especially the . . . (Ha! you were ready for a facile brand quip here, right? Not this time.)

You might think, if you’re utterly mechanically ignorant, that it makes no sense to waste money and space on tools you don’t know how to use anyway. Au contraire—if something goes wrong and you need the assistance of strangers, the least you can offer them is the tools to render that assistance. At a minimum, even on a brand-new Land Cruiser you should carry enough to make what I call generically “rubber repairs,” involving the replacement of pliable things such as fan and serpentine belts, and radiator and heater hoses. These are items that can fail or be damaged even on a new vehicle. A set of standard and Phillips-head screwdrivers, a socket and ratchet set, and a set of combination wrenches will suffice to start (note that for our purposes I consider tire-repair tools a separate subject). But if you want to cover more than first base, you'll need a few additional items.

Okay, so you’re going to buy some tools. You take a look around the web and find, for example, one set of metric combination open/box-end wrenches, from 10mm to 19mm, for $14.95, and another set of the exact same number and size wrenches, from a different manufacturer, for $298 (I am not making up these prices). You’d be forgiven if your brain texts to itself, WTF? We’re not talking about the difference in value between a Corvette and a Carrera here—this is more like Tata Nano versus Aston Martin Vantage. At least with the cars it’s easy to spot a few differences besides the fact that they’re both designed to go from point A to point B. The wrenches don’t even have any moving parts, and appear more or less identical. What gives?

Three factors contribute to the discrepancy: quality, reputation, and pure status.

Quality on even something as simple as a wrench can vary tremendously. Consider what goes into its manufacture:

- What is the alloy used in the steel—plain carbon? Chrome molybdenum? Chrome vanadium?

- How is the tool formed—is it machined, cast, or drop-forged? Drop-forging helps align the internal grain in the steel, increasing strength.

- How is it finished? If chromed to resist corrosion and dirt, what process was used?

- How precise are the tolerances? This is a critical factor in how well the wrench performs—sloppy tolerances increase the chances the wrench will strip a tight bolt or nut.

- Does the box end of the wrench employ the superior “Flank Drive” system pioneered by Snap-on and now copied everywhere? Look for rounded rather than sharp teeth; these bear on the stronger flats of the nut rather than the corners. (The Flank Drive Plus system on new Snap-on wrenches adds the same capability to the open end of the wrench via grooves on the flats. This has been copied by other makers as well.)

- What about ergonomics? Is the wrench long enough to provide adequate leverage (unless it's a shorty designed to fit in tight spaces)? Fully chromed and polished tools don't just look nice and resist corrosion; they're easier to keep clean as well.

- Finally, how socially responsible is the tool? Was environmental protection a factor in the mine-to-maker-to-consumer chain? Do workers in that chain earn a fair wage?

Flank Drive wrench head on the left, standard head on the right

Flank Drive wrench head on the left, standard head on the right

It’s nearly impossible for a consumer to evaluate many of these parameters accurately. A tool marked “drop-forged” could be forged to low tolerances with poor-quality steel. One has to wonder if the wrenches in that $14.95 set were made by a laborer in his or her 60th hour of work that week, and if the smelter or factory do anything to reduce their emissions. It’s sheer common sense that for ten wrenches to be produced in Asia, shipped across the Pacific Ocean, trucked to a Harbor Freight store in Topeka, and sold at a profit for 15 bucks, something along the line had to give: quality, ethics, or both.

That’s where reputation figures into the equation. Although it’s not a guarantee, buying tools from manufacturers with solid reputations for quality at least makes it far more likely you’ll be getting a good product either produced in the U.S. or under decent conditions elsewhere. I’m referring here to such makers as Sears Craftsman, Kobalt, Proto, S-K, and Husky. A set of wrenches from those makers will cost more than $14.95, but it’s very probable the extra expense will be worth it on several levels.

Finally, there’s status. The “boutique” tool makers such as Snap-on (the producer of that $298 set of wrenches), and to a lesser extent Mac and Matco, have transcended reputation and moved on to the level of status symbol. There’s little doubt that that set of Snap-on wrenches (which are, just to be clear, certainly the best on the market) could be duplicated in every detail and sold for much less, but the Snap-on (or Mac or Matco) label adds a premium eagerly paid by both professional mechanics and well-to-do (or savvy, see below) amateurs. The reason is that, tool snobbery aside, these companies have stayed at the very forefront of tool development and quality. If you pay the premium prices for tools from these manufacturers, you can be absolutely certain you're getting the best tools with the most advanced features.

What to buy then? I’ll continue to repeat it for as long as it takes to make it into one of those 1001 Famous Quotes books: If you’ve brought out the tools, something has already gone wrong. Why risk compounding the situation by using cheap tools to try to fix it? I recently read an article on bush repairs in a respected Australian four-wheel-drive magazine, in which the writer opined, “Your tools don’t have to be good, just good enough.” And how, exactly, do you identify that fine line of “good enough” except when one breaks at the worst possible time and you’re left holding a handle and thinking, Hmm . . . not good enough.

So, fine—just go stop a Snap-on truck, hand the driver your AmEx card, and say, “Tool me.” Except that very few of us can afford that option. Instead, I suggest prioritizing.

The most critical component of an automotive tool kit is the ratchet and socket set. This is what you’ll be using for any serious repairs, and its various pieces are the most susceptible to poor quality control. The ratchet head encloses a lot of very small parts that can be put under enormous strain. It’s easy to make a strong ratchet head with a coarse (i.e. 24 or 36) tooth count, but such ratchets need to be turned many degrees to engage the next tooth—a real issue in tight spaces. The best ratchets these days have 72, 80, even 84-tooth heads, yet are immensely strong. The sockets themselves need to be as thin-walled as possible to fit over nuts in tight spots, yet stout enough not to split. That mandates the very best steel and the tightest tolerances.

If you’re putting together a complete tool kit, you’ll probably want one socket set in 3/8ths-inch drive, and another in 1/2-inch drive. The 3/8ths set is for general use; when something big needs fixing or replacing the 1/2-inch stuff will come out, so that’s the most critical in terms of quality.

Next are the wrenches, which do many of the same tasks as sockets but have the advantage of no moving parts. Nevertheless, quality is key—in many situations you’ll need a socket on one side of a fastener and a wrench on the other. I’ve only broken one wrench in my life, but I’ve used many that fit poorly.

So my advice is to spend until it hurts on your ratchet/socket sets, a bit less so on the wrenches. Next on my list would be a really good set of screwdrivers. After that, you can economize on many pieces with little risk of failure in the field.

A good place to compare quality in one spot is a Sears store. Take a look at ratchets. Their new, green-handled Evolv series (what’s with the cute missing “e” anyway?) represents the price-leader, and it shows. Pass. Move up to the standard Craftsman stuff—non-polished, coarse tooth count, but smoother. Now look at the fully-polished, thin-profile handles. Nicer and more comfortable, easier to keep clean, although the tooth count still feels fairly low. Finally, look at one of the Premium Grade products: Sealed head to keep out grime, industry-leading 84-tooth ratcheting mechanism that goes snicksnicksnick instead of click click click. My only complaints are the lack of a socket-release button, and the fact that the feel of several I tried seemed to vary slightly, as though manufacturing consistency wasn’t quite spot-on.

Standard Craftsman ratchet, top, fully polished, bottom. Both unfortunately have plastic selector levers, but are solid tools. The standard ratchet is now made in China.

Standard Craftsman ratchet, top, fully polished, bottom. Both unfortunately have plastic selector levers, but are solid tools. The standard ratchet is now made in China.

For several decades I relied on Craftsman ratchets and wrenches, with only a scant few split sockets to their discredit during field repairs (replaced with no questions asked at Sears . . . after I got home of course). Recently I decided to up the ante. I started haunting eBay, looking at Snap-on socket and wrench sets. There were a few decent deals, but nothing spectacular—until I realized that the sets on offer that were missing a piece or two went for much less than the complete sets. Soon I snagged a lot of current-production 1/2-inch sockets, from 12mm all the way up to a giant 36mm, missing only a 19mm, which I quickly added on an individual auction. Same thing with a wrench set from 6mm to 30mm, missing the 14 and 17, again easily replaced.

My one retail splurge was the 1/2-inch ratchet handle. I consider this the single most critical tool in my kit. If I break out the 1/2-inch sockets, it’s usually because something significant has gone wrong with either my own vehicle or someone else’s. And if your ratchet handle breaks removing the 21mm bolts from a transmission bell housing, you can bet you won’t be getting them off with a pair of Vise-grips. So I went to the Snap-on website and plunked down $164.95 for part number SF80A: an 18-inch-long, flex-handle ratchet with a Swiss-watch-smooth 80-tooth mechanism—astonishing on a ratchet with a foot and a half of leverage, but Snap-on uses the same head on a 24-inch handle, so they obviously have confidence in it. The locking flex head gives this ratchet great flexibility, the length makes it an effective breaker bar for the tightest bolts, and the fine-toothed mechanism requires only 4.5 degrees of swing to engage the next tooth, a boon in restricted quarters. Every time I use it I’m impressed, and swear it makes me a better mechanic than I really am. It certainly makes me look like a better mechanic than I am.

Worth every penny: The Snap-on SF80A 1/2-inch ratchet.

Worth every penny: The Snap-on SF80A 1/2-inch ratchet.

With these two fine sets in hand, I began contemplating my entire traveling tool kit. Specifically, I started musing on a question that had been at the back of my mind for some time: Would it be possible to assemble a high-quality tool kit that could handle virtually any field repair up to and including such things as clutch or differential replacement, suspension work, hub disassembly, or cylinder-head removal—in other words, the types of repairs one might expect on an extended overland trip in remote areas—yet still fit inside one manageable case?

Interesting idea. Time to look at some Pelican cases.

Next: a compact, high-quality 3/8ths-inch socket set. Read part 2 HERE.

Irreducible imperfection: The flimsy

At the beginning of the North Africa Campaign in WWII, the British faced a logistics problem on a scale they’d never imagined. In this, the first totally mechanized war, the need for fuel staggered existing supply lines—and existing supply containers. For several decades the British military had made do with a squarish four-gallon soldered-tin can known officially as a POW can—for Petrol, Oil, and Water—to move the bulk of its petrol supplies. The four-gallon size was light enough to be handled by one man (unlike the common 55-gallon drum), and small enough to be transported by light truck or even motorcycle.

But as General Wavell in Cairo mustered his tanks, trucks, and airplanes to counter the forces of the Italians and Germans massing in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (now Libya), the deficiencies of the POW can quickly became all too clear. Stacked in pallets on cargo ships, the weight of the top layers simply crushed those below, resulting in fuel losses of up to 40 percent, and making unloading the intact containers extremely hazardous with thousands of gallons of petrol sloshing around in the bilges and the fumes powerful enough to render seamen unconscious, not to mention the danger of fire or explosion.

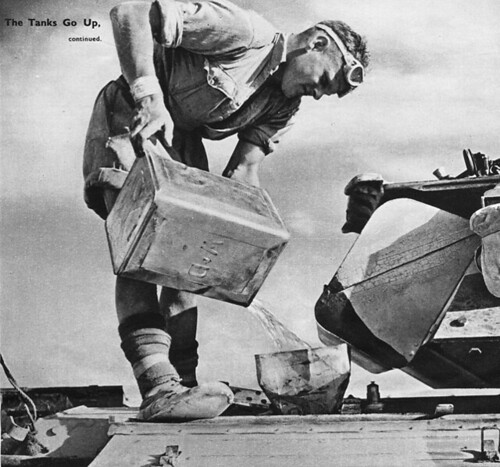

A British soldier refuels a Crusader tank from a flimsy. The funnel appears to have been made from another flimsy.

A British soldier refuels a Crusader tank from a flimsy. The funnel appears to have been made from another flimsy.

Even in smaller shipments the can proved absurdly fragile. Truck transport over 100 miles of desert track frequently left 20 to 30 percent of the contents cascading out the tailgate. In his book The Desert War, Alan Moorehead wrote, “The great bulk of the British Army was forced to stick to the old flimsy four gallon container, the majority were only used once. We could put a couple of petrol cans in the back of a truck, two hours of bumping over desert rocks usually produced a suspicious smell. Sure enough we would find both cans had leaked.”

That adjective, “flimsy,” quickly became a noun, and the POW can became universally known as the flimsy, reviled by troops and brass alike. To get an idea of the numbers used, consider that a single Wellington bomber flying a single nine-hour sortie needed 270 flimsies to fill its tanks. Piles of empty containers 30 feet high stood outside every airbase, and littered the Western Desert wherever British vehicles ranged.

Fortunately, an alternative presented itself when the retreating German Army began abandoning its own 20-liter containers. These were of embarrassingly brilliant design—perimeter-welded of stout steel for strength, with a three-handle configuration that allowed one man to carry two empty cans with one hand (or two full cans if he was strong), and which facilitated effortless hand-off of full cans down a line of men. The leak-proof cap was secured with a fast and foolproof lever, a breather allowed fast pouring, and a clever air trap at the top meant that a full can of petrol would float in water. The British scrounged all the “jerry cans” they could, and in England the design was unashamedly copied to the last detail—two million of them would be sent to North Africa before the end of the campaign. (The U.S. copied the design as well, but substituted cost-saving—and inferior—rolled seams and a screw top that was difficult to seal.)

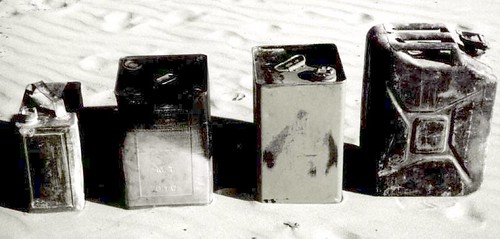

A British two-gallon container, early and later "improved" four-gallon flimsies, and the vastly superior German 20-liter fuel can. Note the thin and awkward handle of the flimsy.In the meantime, the flimsy proved happily more useful as a makeshift device than it did in its primary role. Filled with sand, it became an impromptu building block for gun emplacements and buildings. Cut in half and filled with petrol-soaked sand, it was used as a stove for boiling water (in another half-flimsy), and known as a Benghazi burner or Benghazi boiler (the latter term was subsequently applied to the Thermette, an early volcano kettle supplied to troops from New Zealand).

A British two-gallon container, early and later "improved" four-gallon flimsies, and the vastly superior German 20-liter fuel can. Note the thin and awkward handle of the flimsy.In the meantime, the flimsy proved happily more useful as a makeshift device than it did in its primary role. Filled with sand, it became an impromptu building block for gun emplacements and buildings. Cut in half and filled with petrol-soaked sand, it was used as a stove for boiling water (in another half-flimsy), and known as a Benghazi burner or Benghazi boiler (the latter term was subsequently applied to the Thermette, an early volcano kettle supplied to troops from New Zealand).

The Benghazi burner was also effective for illuminating rough landing strips at night—and that was quite possibly the role played by the crudely bisected Shell example we found in Egypt’s Western Desert this February (top photo). It speaks to the extreme aridity of this eastern edge of the Sahara that after 70 years even something as thin as a flimsy was still in recognizable shape.

The anti-tactical knife

It’s easy to become jaded viewing recent knife designs, 99 percent of which are chasing various black-ops/street-fighter/wilderness-survival fads. “Tactical” folders with assisted opening, black-oxidized blades, and tanto points? Yawn. (Ever tried to sharpen the corner on a tanto point?) Sheath knives with Kraton handles, half-serrated edges, and saw teeth on the back? Pass. Gerber’s Bear Grylls “Signature” knife includes a pocket survival guide and an emergency whistle on the lanyard cord. (“TWEEEET! Somebody help! I can’t get reception on the Discovery Channel!”)

I suppose one could ask just how much true original thinking we can expect in this oldest of all Mankind’s manufactured tools. You have a handle, and a blade. How much innovation is really possible? Also, to be fair, it’s beyond doubt that steel technology has progressed substantially the last couple of decades. Top-end modern blades now combine toughness, strength, and edge-holding in levels unimaginable just two decades ago. And in the end, the steel is really what a knife is all about.

Nevertheless, when I scan knifemakers’ booths at venues such as the Outdoor Retailer show, it takes something special to stop me in my tracks. Last Saturday, on a tip from Mario Donovan of Adventure Trailers, I strolled past the Baladéo booth—and stopped in my tracks.

On a plexiglass display stand stood an impossibly slender folding knife, a mere wisp of stainless steel accented by an even fainter wisp of black G10 scale material. The spine of the blade and the back of the handle comprised a single graceful curve. It was knife design reduced to, as the writer Thomas McGuane once described an elegant skiff, a “simple linear gesture.”

I expected it to be light, but I was unprepared for just how light. The model I held is called the 37G, for its weight in grams. That’s less than an ounce and a half, just hardly even there (and the company makes a smaller model called the 15G). For comparison, my Chris Reeve Sebenza (below), with titanium scales and a blade the same 3.75" length, weighs 130 grams. Despite this, the Baladéo's blade lockup felt good, and the knife is user serviceable via tiny Torx fasteners. The G10 mini-scale is one of several options (including a scaleless version at 34 grams). Also available is a limited edition (300 pieces) 37G in cooperation with climber Conrad Anker, the proceeds of which will go to support Anker’s Khumbu Climbing Center in Nepal, a school that trains local Sherpas in climbing techniques and safety.

Okay—let’s be clear. You won’t be using the 37G to saw your way out of the cockpit of your F/A 18 after being shot down behind enemy lines. You won’t be making a spear out of it with a stick and your unravelled paracord bracelet. In fact, you won’t be doing any of the things those “tactical” knifemakers assure you can be done with their products, which no one ever does anyway.

Even in the real world, this is a specialized implement. It would never work for field dressing large game, or making feather sticks for fire lighting. Opening shipping cartons? Well, sure, but slightly beneath contempt. That’s a job for a Swiss Army knife or a multitool. It certainly won’t take the place of a substantial piece such as the Sebenza.

Instead, here’s what I envision. You’re at an upscale restaurant with several acquaintances. The filet mignon you ordered has arrived, but the knife provided is either woefully inadequate or one of those coarsely oversized serrated saws. You produce the 37G from the inside pocket of your sport coat, open it with a deft twist, and slice away. Around you, conversation stops as everyone stares at the elegant blade, then demands to see it. Across the table, the guy who showed up in shorts, a T-shirt, and flip-flops, who was already squirming under your tolerant but dismissive glances, is instantly, totally emasculated, and says not another word about his new quad the entire night. In fact he skips dessert and leaves early.

You’ll think of other scenarios. Slicing cheddar and peeling oranges at a picnic? Nice. Gutting a freshly caught brook trout? Excellent. Opening Christmas presents? Perfect.

Criticisms are scant, accepting the design parameters and featherlight construction. The steel is utterly pedestrian 420 stainless—perfectly adequate for any task this knife will handle, and it keeps the price down to under $50. But it would be nice to see a premium option for us helpless steel snobs. Also, the blade has a chisel grind, bevelled on only one side (calling to mind my vintage Puma Trapper’s Companion). I find chisel grinds a bit more trouble to sharpen, and will unceremoniously convert this one to a standard grind the first time it needs work (the edge is completely protected when closed so this represents no hazard). Finally, if you grip the knife the wrong way it’s possible to accidentally release the Walker liner lock that keeps the blade open. The best grip is a squeeze between thumb and index finger on either side of the pivot bolt.

Those minor issues aside, this is one of those tools that will bring a smile to your face whenever you use it. I liked it enough to buy two—a G10 for me and a Conrad Anker model for Roseann.

However, in case you were wondering, the 37G does not come with an emergency whistle.

Above: 37G with G10 scale. Below: Conrad Anker edition to benefit the Khumbu Climbing Center.Baladéo G Series knives

Above: 37G with G10 scale. Below: Conrad Anker edition to benefit the Khumbu Climbing Center.Baladéo G Series knives

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.