Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

A better Hi-Lift handle keeper?

If you own a Hi-Lift jack, you’ve probably dealt or struggled with the issue of how to lock the handle firmly in place during transport.

The spring clip that comes on the jack is worthless (and not designed) for that purpose. The polyurethane collars that slip over the handle and shaft are okay, but in my experience they stick when new, and eventually wear and slip down on the jack if it’s stored upright, or vibrate right off the end if it’s stored horizontally. For a time I just used a piece of One-wrap (hook-and-loop tape), but I’m not a big Velcro fan, and it quickly clogs with dirt when used in such an application.

A few years ago I set out to make something better. With an old sheet of half-inch-thick HDPE plastic—I don’t even remember what from, perhaps a cutting board?—I started playing around with ideas, and eventually came up with what you see here.

It slips easily over the shaft and handle of a Hi-Lift, and you can lock it anywhere you like with the two through-pieces and then the spring clip. It can’t slip. The only disadvantages I’ve found are that it won’t slide over the removable clamping foot if you keep one attached (although you could modify the opening so it could), and it has multiple pieces that might be prone to loss. However, I think it would be easy to modify it with a safety wire that would keep all three plastic bits together.

Always remember to store your Hi-Lift with the operating lever in the “lift” position.

P.S. If you don’t want to make your own, Step22 Gear has a promising alternative, here. I just got one and will be reviewing it soon.

Hilux news and rumors

Yes, it’s time to torture myself and you with updates on the Toyota truck we wish we could get in the U.S. You know, the one with the fully boxed chassis and turbodiesel powerplant?

First up is the announced Hilux GR (above), an apparent stab at a Toyota version of Ford’s Ranger Raptor (which we also don’t get). In contrast to the regular Hilux’s 2.8-liter four-cylinder turbodiesel, which produces 174 horsepower and 332 lb.ft. of torque, it’s rumored the GR will have a V6 turbodiesel making upwards of 270 horsepower and a staggering 480 lb.ft. This is apparently the same engine that will be in the upcoming 300-Series Land Cruiser.

On a more basic level the Hilux is expected to get a facelift next year, prior to a redesign in 2023. Whether this image is accurate or a rendering we do not yet know.

The further rumor is that the redesigned Hilux will be merged with the U.S.-market Tacoma to return to the single world-platform pickup Toyota sold until the introduction of the Tacoma for us soft Americans.

I’ve been hearing this rumor since 2015, so I’ll wait and see.

Then again, we finally got the mid-engined Corvette. So miracles do happen.

Anti-Gravity Batteries' Battery Tracker

I’m not much of a mobile phone person—in fact I hate the things and would happily revert to a black Bakelite dial phone in a little nook in the hallway. But such is no longer the way of the world.

One bright spot of the new world is the availability of apps, which tend to be far more useful than the average actual phone call. I have the Star Walk astronomy guide—which is pure magic—and a bird guide that not only has descriptions and photos but will play the bird’s song for you. Brilliant. Motion-X GPS of course, and several practical tools such as inclinometers and an OBDII reader.

But way too many apps seem to exist just because they can. I recently got an otherwise excellent LED flashlight to review, the programming of which is accomplished with an app. Seriously? I need to clutter my phone with another program just to tell my flashlight whether to come on bright or dim when I push the button? Absurd.

Thus—even though I’ve been a fan of Anti-Gravity Batteries and their superb Micro-Start since the beginning—I wasn’t sure about their Battery Tracker, which is also paired with an app. Nevertheless I decided to give it a try.

The Battery Tracker is designed to let you monitor battery status via a smart phone. Okay, let’s see how it works.

Well, it works about as simply as one could imagine. Use your smart phone to scan the squiggly square thing on the package. (Roseann chimes in: “Uh, that’s called a QR Code, Mr. Gates.”). And bink, there’s the (free) app. Hook the wires on the tracker to the positive and negative terminals of the battery, and you’re done. The phone pops up with the voltage. I was disappointed the tracker didn’t come with a penny’s worth of double-sided tape to adhere it to the battery, but we had some.

Okay, battery voltage. Wirelessly. I can check it from the living room. I still wasn’t really getting it, so I kept reading the instructions. Aha: you can set the tracker to send you an alert if your battery’s voltage drops into the danger zone. That’s cool. It will also run a cranking test and a charging test to confirm adequate starting power in the battery and adequate charge from the alternator. Definitely a smart thing to do before a major trip.

And yet. I still wasn’t quite fully sold on it for my own use.

Finally I realized the problem. There was nothing wrong with the product; I was just using it on the wrong battery. I swapped it from the starting battery to the auxiliary.

Suddenly it was brilliant.

Our auxiliary batteries are the ones that are working all the time, to run fridges, lights, chargers, and inverters. Some of us install voltmeters in the system to monitor them, but you need to get up from the Kermit chair and go look at it, leaving your campmates ample time to steal your drink and gorge on the snacks. Others of us simply guess how long we can go without charging until the low-voltage cutout on the fridge kicks in. Now a simple glance at the phone will tell you if it’s time to re-orient the solar panels or go for a drive. And the tracker can alert you before the beer gets warm.

But that’s not all. The tracker can give you a 31-day record of charge condition. This would be perfect when setting up an auxiliary battery system, especially with solar input. You can determine if the all-important float voltage is being reached every day—critical to long battery life.

At $36 the Battery Tracker is reasonably priced, and could be used to significantly extend the life of your auxiliary (or main) battery, saving its cost several times over.

Anti-Gravity Batteries is here.

Why you need the new edition of Tom Sheppard's Four-by-four Driving

If you want to be a better driver— and who doesn’t no matter what level we might consider ourselves to be at the moment?—and you don’t have this book, you need it. Trust me on this.

Full disclosure: I receive a bit of commission on every copy sold in the U.S., and I contributed the sections on winching and Hi-Lift/ARB jacks. But that’s not why I want you to buy it.

The reason you need it is because there is no other instructional book on four-wheel-drive technique that does what Tom Sheppard does in this one.

Four-by-four Driving doesn’t simply tell you how to drive in different situations. As the blurb on the back cover states, “I.T.D.S.—It’s the Driveline, Stupid.”

Knowing how to drive is great. Knowing why the vehicle does what it does, knowing how different drivetrains operate and how each reacts to differing terrain, knowing the strengths and weaknesses of each type of four-wheel-drive system, and learning how to exploit those strengths and accommodate those weaknesses, will turn you from a competent driver into a master of the machine and the terrain. I still learn or am reminded of those lessons every time I open my copy.

You can, if you like, just read the section in Four-by-four Driving that covers your own vehicle, but you’ll gain much more if you read through the descriptions of drivetrains and operating systems of vehicles around the world. Not only can you master your Tacoma, you’ll be able to hop in a friend’s Discovery or Wrangler or G-Wagen and master it too. In fact if you dedicate yourself to the first part of this book you could probably be air-dropped anywhere on the planet and stand a good chance of knowing how the dominant local transport works. Suzuki Jimny? Sure. Skoda Karoq Scout? Yep. On the off chance you find yourself in a Rolls Royce Cullinan, you’ll be right at home. And this edition includes, among other updates, full technical details of the new Land Rover Defender. (If you already own the fifth edition, note that the Defender coverage comprises the majority of changes to the sixth.)

Only after explaining drivetrains, traction-control systems, suspensions, and operating systems does the book start in on driving techniques, beginning with what I consider to be the basic skill that must underpin all others: mechanical sympathy.

Then, yes: You’ll learn how to drive on sand, mud, ice, and rocks. You’ll learn how to handle ruts, side slopes, water crossings, hill ascents and descents. Following this comes a chapter on recovery, both solo and assisted (and that brilliant section on winching . . . ).

Finished? Not even close. Now comes a section on advanced driving. If you ever find yourself plopped in the driver’s seat of a 60-year-old Bedford truck with a non-synchro gearbox, you’ll learn how to handle it. Or, want to show off by shifting the transfer case in an FJ40 or Series Land Rover from low to high range, while moving? That’s in there too.

Following all this are sections on expedition basics, tires and tire pressures, loading and lashing, oil types and grades, fuel, water . . .

But it’s in Four-by-four Driving’s former-RAF-test-pilot level of detail explaining how four-wheel-drive vehicles do what they do that the real gold of the book lies. Which explains why, unlike those 30 different watches you can buy that all claim to be “Used by Special Forces,” Four-by-four Driving actually is used as a training manual by special forces in both the U.K. and the U.S. It’s worth every penny.

Available right here.

World's most exclusive used overlanding vehicle?

Of course one could make an argument for John Steinbeck’s Rocinante—but that’s in a museum. You can actually buy Steve McQueen’s 1952 Chevrolet 3800 and camper from the Legendary Motorcar Company. Note that “can” is highly subject to your financial status. The company doesn’t list the price; you have to “enquire.” From their description—which I’ve edited for grammar, ahem:

This special 1952 Chevrolet 3800 Pickup with custom camper was purchased by the legendary Hollywood actor Steve McQueen from a migrant farmer he passed on the side of the road in the late ‘70s when he resided in Trancas Beach, north of Malibu, California. An avid collector of vintage cars, trucks and motorcycles throughout his lifetime he owned more than 60 rare vehicles including a 1951 Hudson Hornet, a 1956 GMC Suburban, a 1931 Lincoln Club Sedan, a 1946 Willys Jeep, and a 1935 Chrysler Airflow Imperial Sedan. This 1952 Forest Green Chevrolet 3800 series is a one-ton step-side long-bed. Powered by the original 235 cu in Loadmaster 6-cylinder engine with a 4-Speed manual transmission.

McQueen understandably used the truck for cross-country camping trips as this Chevrolet pickup truck features a custom camper known as "Dust Tite.” The custom camper was built by Harold Van Hoosen, a sheet metal fabricator from Yreka, California, in October 1952.

Made of galvanized metal and aluminum, the camper includes a double-size bed, storage cabinets, drawers, shelves, and a heavy-duty diamond-plated rear bumper. Inside the famous Chevy 5-Window cab design, complete with sun-visor, the two-tone green bench seat is in wonderful condition. The interior has a pretty high trim level for a truck of this era and has an AM radio and Chevy heater. It also has a platform on top, making it a prime viewing location for auto and motorcycle racing events. Other features of this wonderful truck include five-gallon gas tanks on the running boards, driver's side spotlight and two toolboxes.

In case you’re in the market, LMC is here.

Not so simple: The simple redirected winch pull

Take any reasonably comprehensive winching course and, once you’ve covered the basic single-line pull, you’ll be introduced to the snatch block—or, more recently, its elegant one-piece alternative, the billet-aluminum recovery ring.

A pulley—which is what both devices are—serves a couple of purposes in a winch system. Most impressively, when a winch line from a vehicle is led through a pulley attached to an anchor and then back to a recovery point on the vehicle, the power of the winch is essentially doubled (minus minor frictional losses) while line speed is halved. (A corollary to this is that by pulling more line off the winch to rig a double-line pull, you are further increasing the power of the winch by reducing the layers of line on the drum. Thus you receive a double benefit during a difficult recovery.)

The other valuable use of a pulley is to redirect a pull—around a corner as it were—when a straight one is either awkward, dangerous, or impossible. It’s frequently used to recover a bogged vehicle when a recovery vehicle equipped with a winch cannot be positioned directly in front of it. A suitable anchor such as a tree is employed as a redirect point, using a tree strap and a pulley.

When you learn how to rig a redirected pull you’ll also learn that this use of a pulley does not multiply the power of the winch, nor does it halve the line speed. The easiest way to figure out whether or not you are multiplying winch power in any situation is to count how many lines are shortening when you engage the winch. For example, in the illustration below labelled Double-line Pull, both the line from the winch to the pulley and the line from the pulley back to the vehicle will shorten as the winch pulls, thus the power is multiplied by two.

On the other hand, in our simple redirected-pull scenario above, only the line running from the pulley to the bogged vehicle will shorten—the distance between the pulley and the winching vehicle will not change. Therefore the winch is operating at its rated power.

But now comes the not-so-simple part. What about the load on the anchor?

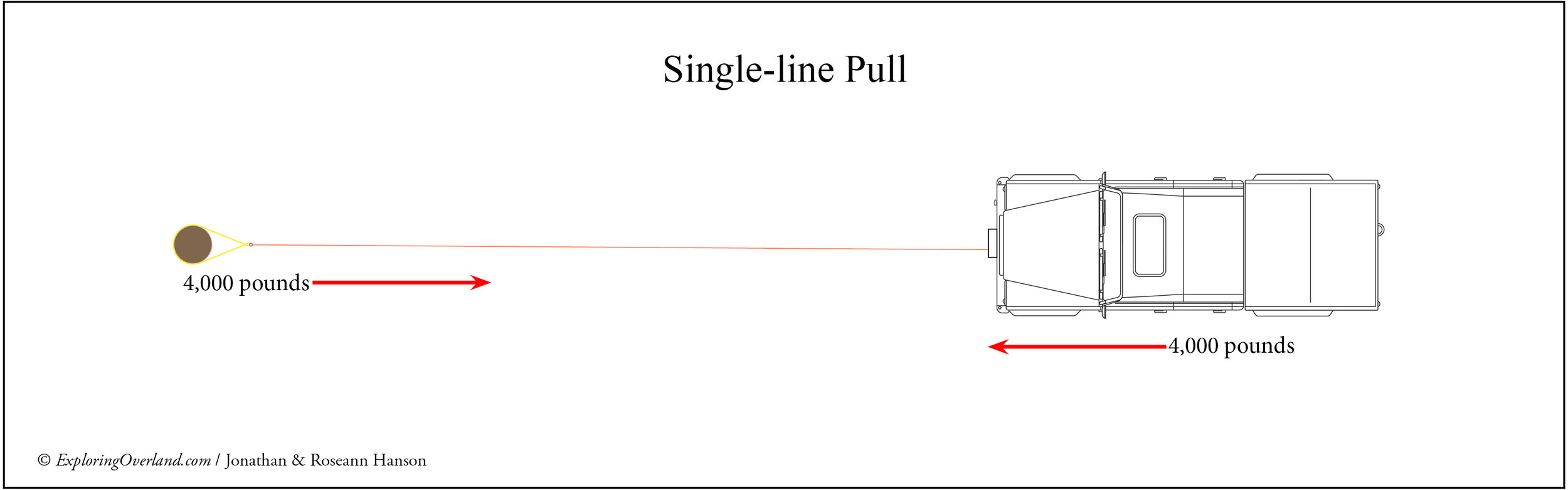

Let’s assume that in all our scenarios, the bogged vehicle needs 4,000 pounds of pull to retrieve it. If the operator rigs a single line pull to the tree anchor directly in front of the vehicle and engages the winch, the load on both the winch and the tree is 4,000 pounds.

If the operator rigs a double-line pull, the vehicle still needs only 4,000 pounds of pull to move. Due to the effects of the pulley the load on each line is halved, to 2,000 pounds; thus the winch is only exerting 2,000 pounds (and only drawing the amperage necessary for that), and the recovery point on the vehicle is also experiencing 2,000 pounds of force. The load on the anchor remains 4,000 pounds.

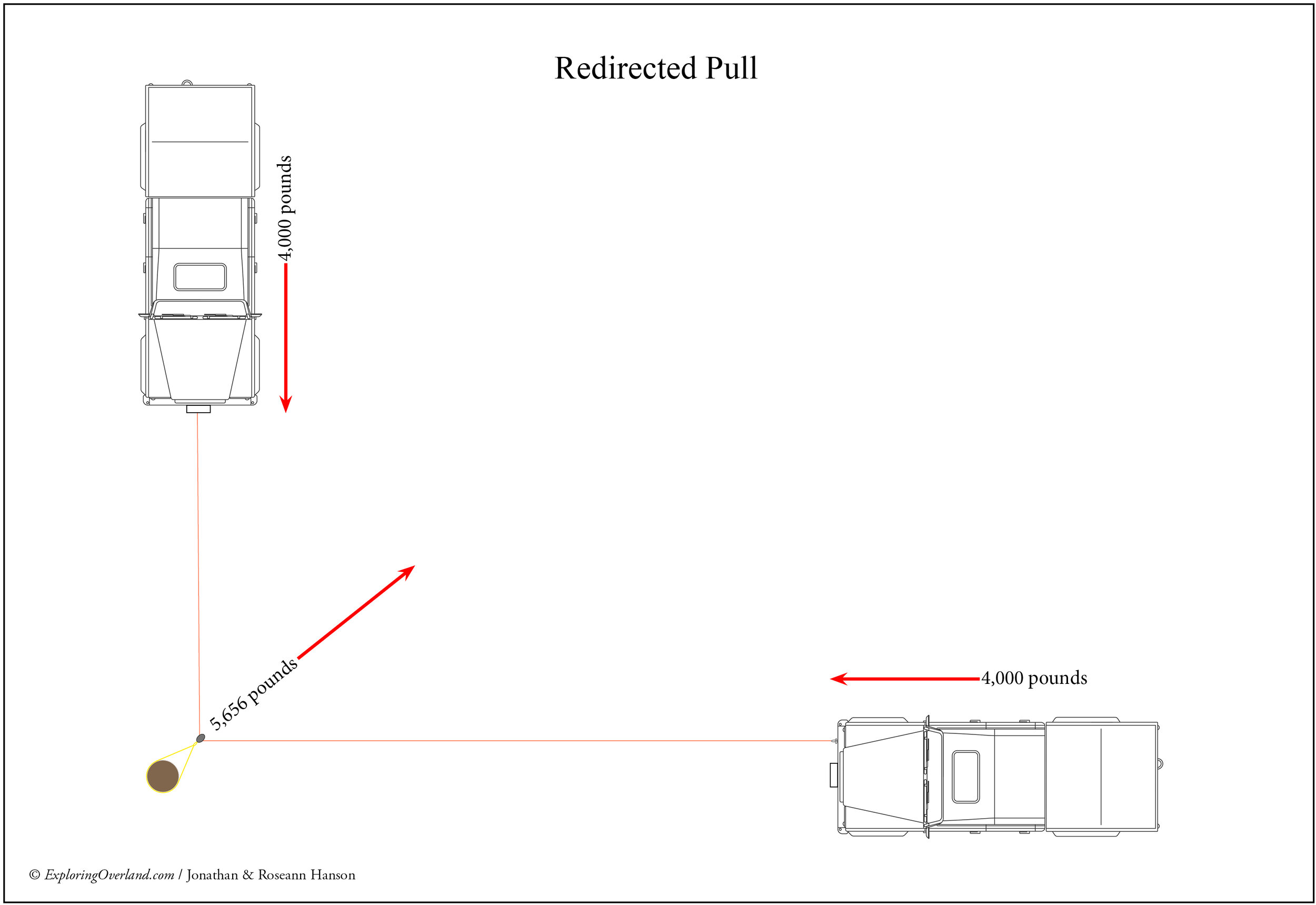

So far so good. Now let’s take another look at our redirected pull, where one vehicle is at 90 degrees to the other. In this scenario, the bogged vehicle still needs 4,000 pounds of force to move. The winch on the recovery vehicle is also subjected to 4,000 pounds—again taking into account slight frictional losses. So the force on the anchor must also be 4,000 pounds, right?

Actually . . . no.

In this case—a 90-degree redirected pull—the force on the anchor will actually be 5,656 pounds, almost 50 percent higher. The force is calculated using the formula:

pull = 2t(cosine x)

. . . where pull is the force on the anchor, t is the force exerted by the winch, and x is one half the angle at which the winch line passes through the pulley (in other words, the direction in which the anchor would move if it failed; in a 90-degree redirect it would be 45 degrees).

So, in our case, 2 x 4,000 pounds is 8,000, multiplied by the cosine of 45º which is .707, equals 5,656 pounds.

There’s more. As the angle between the bogged vehicle and the recovery vehicle narrows, the force on the anchor continues to increase. Imagine the scenario below, in which the recovery vehicle has to be situated directly alongside the bogged one—I’ve been in this situation. In this case, with the angle between the winch lines near zero, the force on the anchor would be (very nearly) doubled, to 8,000 pounds—even though the bogged vehicle is still only subject to 4,000 pounds of pull to free it. Imagine a tougher scenario in which the recovered vehicle took the full might of, say, a 10,000-pound winch to free it. In such a case that pine tree you wrapped your strap around is going to have about 20,000 pounds of force trying to pull it over—and all the hardware attached to it will be subject to the same stress.

You don’t actually have to have a calculator with a cosine function to figure the increase in force if you use a chart such as this, where “factor” equals how much the force on an anchor is multiplied by different angles of redirected pull :

And, in reality, you don’t need to do any figuring or checking at all. All you need to remember is that in any redirected pull, the force on the anchor can be up to twice what the rest of the system is subjected to. And the anchor includes the tree or chocked vehicle or whatever you are rigging to, as well as the tree strap, shackle, and pulley in the anchor assembly.

Non-instinctive effects of physics such as this reinforce the axiom always to use recovery equipment rated for the vehicle and winch, with working load limits (WLL) clearly marked, and adequate safety factors.

Learn how to winch online! Or not.

The greatest thing about the Worldwide Web is the vast amount of information accessible with a few clicks of a computer mouse.

The worst thing about the Worldwide Web is the vast amount of mis-information accessible with a few clicks of a computer mouse.

As part of my explorations of the online overlanding world, I occasionally browse through instructional YouTube videos, and I am frequently reminded how many of them should be called “instructional” videos. Sometimes the information in the latter type is harmless. Other times it is decidedly not harmless. That especially applies when the “instruction” is about winching.

Consider the video I have bookmarked in which the host attempts to demonstrate the party trick of moving a vehicle backward with a front-mounted winch. In essence this is a simple and virtually worthless procedure that involves running the line from the winch through a snatch block anchored to a tree in front of the vehicle, then to another attached to a tree behind the vehicle, then back through a third snatch block mounted on the vehicle’s rear recovery point, and finally to an anchor. When the winch is engaged the mathematics of the line being pulled results in the vehicle moving slowly backward. Aside from the fact that very few of us carry three snatch blocks, the odds of anchors being in exactly the right spot to rig this system where you might get bogged are scant. Our host got around the problem of multiple snatch blocks by simply using shackles instead—with steel winch cable. Ouch. He also utilized a child’s car seat as a winch line damper. Needless to say his attempt failed. However, the furthest anyone really needed to go with this “instructional” video was a glance at the fellow’s “spooled” winch cable.

A rat’s nest just begging for a snarl or jam.

In another demonstration of reverse winching, a cheerful Aussie bloke uses a kinetic strap as a tree saver—pretty much the most egregious never-do-this move you can make when rigging a winch recovery.

However, a recent video I watched, from Bold Canyon Outdoors, was in a way even more confusing, as it boasted decent production values, a well-spoken host, and significantly better equipment. The video offered a basic guide to winching, including a single, double, and triple-line pull.

It started out with a bit of humor, which was fun. But after the host brought out the winch kit he was using—and heavily promoting—from a company called Gear America, and began discussing the procedure, things began to go south. If I went through the video again I could probably pick out more goofs, but what I noticed immediately included the following.

First, he simply introduced a Jeep Wrangler with a winch. He said nothing about winch selection, sizing, mounting—the winch was simply there, taken for granted.

Then, when he introduced the “Gear America Ultimate Winching and Rigging Off Road Recovery Kit” (yes, really), he made no mention of matching the kit to the winch, no mention of working load limits (WLL) or minimum breaking strength (MBS) of the shackles or snatch block. He pulled out a “tow strap” included in the kit. Was it truly a tow strap, or a kinetic-recovery strap? Big difference. You can use an elastic recovery strap to tow with, but it would be dangerous to use a non-elastic tow strap as a kinetic recovery strap. He referred to the bow shackles in the kit as D-rings—not a big deal, you might say, but the little mistakes and omissions were quickly adding up to a not-very-credible presentation.

When the host ran the winch line out to a tree to use as an anchor, he mentioned nothing about choosing an appropriate (i.e. live and large enough) tree to take the strain. He also, critically, failed to check overhead for dead limbs that could be dislodged by the stress of winching. He properly employed a tree saver strap, but positioned it above waist height. A tree strap should be positioned as low as possible to reduce stress on the tree. Finally, when he connected the winch line to the tree strap with a bow shackle, he specified that the shackle pin should be “snug”—an elementary beginner’s mistake. A shackle pin should be snugged, then backed off a quarter turn or so. This is not a safety issue, but a way to ensure the pin doesn’t jam under load.

He then properly advocated employing a winch line damper to help control a recoiling line if a component in the system breaks. He placed the weight in the middle of the line. This is a small point, but I prefer placing the damper closer to the end of the line where the shackle and winch hook are—those are the heavy bits that represent the most danger should either or both come loose.

Next the host demonstrated a double line pull. While doing so, he introduced the Gear America snatch block, and noted that it is “suitable for either synthetic or steel winch line.”

Ugh.

The Gear America snatch block has a steel pulley with what looks like a standard semi-circular groove for the line. That’s perfectly suited for steel cable. A snatch block for synthetic line should ideally have a composite pulley. More to the point, while the steel Gear America pulley could be used with synthetic line, you would certainly not want to do so once it had been used with steel cable, and you most definitely would not want to swap back and forth. Steel cable will leave micro-abrasions on the pulley that are not good for synthetic line. (For the same reason, a winch fairlead—whether hawse or roller—that has been used with steel cable should be replaced if synthetic line is installed on the winch.)

I looked up Gear America, which seems to specialize in low-cost recovery equipment. The “Gear America Ultimate Winching and Rigging Off Road Recovery Kit” actually comprises a pretty basic assortment of kit, including what the website lists as a “tow strap.” Hmm. So I looked up that product separately, and found its description: “Use it as a Tow Strap, Recovery Strap, Tree Saver Strap or Winch Extension Strap, making it an extremely versatile product.”

Oh brother.

I looked at the construction, which is polyester, meaning there will be very little stretch in this thing. Therefore the suggested use as a “recovery strap” is highly problematic, since a recovery strap is commonly made from nylon and designed to stretch and absorb shock when it is used in a kinetic recovery. A novice who had looked at just enough YouTube “instructional” videos to have a vague idea of how to snatch a stuck vehicle could easily break something or rip off a bumper by backing up and taking a run at moving a bogged vehicle with this “multi-purpose” strap. At least the site lists the MBS and WLL of the strap (35,000 and 12,000 lb).

Next I looked at the bow shackles included with the not-going-to-write-it-all-out-again recovery kit—which are actually described there as “D-ring shackles.” They’re 3/4-inch versions, a standard size in thousands of recovery kits, and properly stamped “WLL 4 3/4T,” or 9,500 pounds. With a standard six-to-one safety factor on shackles that works out to a 57,000-pound MBS. However, the description right under the photo of the shackle and its stamp says it has a “10,500-lb WLL and 58,000-lb MBS.” Hmm . . .

9,500 pounds? Or 10,500?

Not to worry about math. Below that is the assurance that you can:

MAKE A BOLD STATEMENT - Our Unique Design Ensures Unprecedented Strength and Looks Amazing on your Jeep or Tuck (sic).

Lastly I looked at the Gear America snatch block, and sure enough it’s listed as being suitable for both steel and synthetic line. Also, the snatch block itself is labeled “9 US ton,” while the description below it says it has a “10,000-pound working load limit,” and an MBS of 10 tons. So . . . which is it, guys? Further, it appears there is no WLL indicated on the product, which could lead a user to assume the “9 US ton” refers to a working load limit—a dangerous assumption.

My impression of the Gear America site, I’m afraid, is that is was conceived and created by some people who thought selling 4x4 recovery gear would be a good business, but who have very little experience with actual 4x4 recovery. Either that or they handed off their website design to someone with no clue, and didn’t do any fact-checking.

Going back to the Bold Canyon Outdoors video, I realized the host was simply parroting most of what the Gear America advertising stated regarding their products. But that’s no excuse: If you’re going to post an “instructional” video that involves a potentially hazardous activity (the one in question has had 8,000 views), you really should strive to get every detail correct.

Total commitment: adding a pop-top conversion

A Mulgo pop-top on a Land Cruiser Troopy, and a Dormobile conversion on a Defender 110, from Sonoran Rovers.

Think way, way back to the Pre-Cambrian Era of the U.S. overlanding scene: say, 2005.

If you were interested in backcountry vehicle-based exploration, what choices did you have for self-sufficient accommodation?

There were plenty of ground tents on the market, from small to large and bad to excellent. If you owned a pickup and wanted a slide-in camper that could withstand regular off-pavement use, you had a choice between the excellent but heavy Alaskan and the excellent and lighter Four Wheel Camper.

And . . . that was pretty much it, unless you owned a rare Land Rover Dormobile. The clever flip-top Wildernest was gone, sadly too far ahead of its time. There were no adventure trailers, no roof tents—and certainly no Earthcruisers or Global Expedition Vehicles.

Today the situation is reversed. We have a bewildering array of options. However, since few people can afford a single-purpose vehicle, the choice for the majority of us comprises a more-or-less mainstream 4x4 passenger vehicle which we then modify to a greater or lesser extent to support multi-day excursions. And if you own a long-wheelbase model such as a Land Cruiser station wagon, a Wrangler Unlimited, a (pre-2020) Land Rover Defender 110, or something similar, the most drastic possible modification is a pop-top conversion, which involves sawing the entire top off the vehicle to install a lifting roof and bed system. What are the upsides and downsides of such a full-steam-ahead approach?

One obvious downside is cost. Pop-top conversions are universally expensive, in the range of $6,000 to $9,000, double the cost of even the dearest roof tents; far more than a free-standing ground tent with full standing headroom and a full suite of accessories. And that initial cost is just for the top and bed, not any interior cabinetry or cooking/washing/refrigerating options.

The other big downside is also obvious: You are permanently altering the vehicle with a giant hole cut in the factory roof. Yes, technically speaking you could reverse most pop-top installations, but it would probably represent a financial hit close to the cost of the conversion itself. For something like a Land Cruiser 60, 70, or 80 series it would involve finding a donor roof from a wrecked vehicle and either edge-welding in the missing bit or replacing the entire roof. It would be slightly easier with a Defender given the Mechano assembly of the roof structure, but still steep.

“What have we done?”

All right—so you’re okay with the cost of a conversion, and willing to decapitate a perfectly sound vehicle. What do you get in return?

Quite a lot, actually.

First, consider setup and weather-resistance. I can hold my breath for the time it takes me to pop the Mulgo top on our 70-Series Land Cruiser Troopy. Most other front-hinged brands are just as quick, as is the side-opening Dormobile roof. Yet wind resistance in the erected structure in all the makes I’ve looked at or tried is superb, since the entire assembly is secured around its perimeter to a 5,000-pound ground anchor, and the hydraulic struts used to raise and support the roof keep the fabric taut. No soft-shell roof tent comes close in un-flappability, and even a high-quality ground tent such as the Springbar would have to be well-staked and guyed to compete—20 minutes of work, minimum.

Once you’ve taken the 30 seconds to raise the top, you have full standing headroom within the footprint of the cargo area of the vehicle. Even if you leave the interior stock, the ability to stand up inside, out of rain and wind, is a blessing. Add cabinetry, a sink, stove, and fridge, and suddenly you have a mini motorhome that will enable you to comfortably wash, cook, and eat inside during the worst weather.

Since the Troopy is right-hand drive, the tall cabinets are on the right, behind the driver. In a left-hand-drive vehicle this would be reversed.

Roseann designed our cabinetry so the Kanz kitchen can be removed and set up on legs for cooking outside.

Ensuring cabinets are correctly sized.

At the end of the day, about five seconds is all it takes to deploy a full-size bed platform and comfortable mattress. In our Mulgo conversion there is enough space to leave all our sheets, blankets, and pillows in place as well, virtually eliminating setup time for sleeping. Hydraulic struts hold the bed up against the roof while living inside. Pull down on the loops and . . . bedtime.

The costs for all this in terms of the donor vehicle’s performance, fuel economy, and backcountry ability are essentially nothing. Our Mulgo conversion raised the factory roof height by 35mm—less than an inch and a half. Thus overhead clearance is barely affected, as are aerodynamics (such as they are in a Land Cruiser Troop Carrier). The Mulgo conversion adds 75 kg (165 pounds) to the vehicle, no more than some roof tent/rack combinations, with a significantly lower center of gravity—and, did I mention, standing headroom? If one considers instead a full-sized ground tent plus cots and mattresses, you’re still looking at only about 100 pounds of actual added weight.

There are a few practical disadvantages: Our Troopy interior is not nearly as roomy as our previous Four Wheel Camper Fleet model, with its spacious transverse front dinette, queen-sized bed (the Mulgo is a double), and interior shower. With the Troopy’s bed platform lowered there is only about two feet of standing space between it and the back door—enough to dress and for access but that’s it. Both of us need to be up to put the kettle on in the morning, unlike in the FWC. But then the Four wheel Camper added 1,000 pounds to our Tacoma, in addition to significant wind resistance on the highway and a noticeably higher center of gravity. Fair trade-offs: We loved both the Four Wheel Campers we owned. We gave up some spaciousness to retain superior four-wheel-drive capability and fuel economy.

Of course, by no means do we hole up inside when camped unless the weather is truly miserable. An Eezi-Awn Bat 270 awning provides wrap-around shade and rain protection, and two clip-on wall sections allow us to arrange a sheltered outdoor room. A clever slide-out table incorporated into an interior bench gives us outdoor eating and work space. Erecting all this adds perhaps ten minutes to total setup time. But the point is, after we put in a 300-mile day on corrugated tracks and pull up somewhere in the dark in a pouring rain, all we have to do is pop the top and we’re home.

Having driven both clamshell pop-top conversions and a Dormobile, I can say that in neither case could I detect any loss of structural rigidity, even on rocky roads and in off-camber trail situations. Plus, you can actually stand and walk around on our Mulgo top’s aluminum roof—not possible on the factory roof. I’ve not noticed any noise difference either; if anything the Mulgo top might dampen it.

The way we designed and built our interior, with permanently attached cabinets, the Troopy is of very little use for anything except traveling. But that was just our approach—if you eschewed cabinetry, or fashioned an interior in modules that could be easily removed, the top itself wouldn’t hinder the day-to-day utility of the vehicle one bit. You could even leave in the rear seat and restrict camping modifications to the rear deck. Our friends Connie and Graham, who bought their own Troopy and traveled with us across Australia and then Africa, had their own Mulgo top installed but left in a drawer system and a simpler interior—personal preference.

Wolf Pack food “pantries” can be accessed in place or moved outside with the Kanz.

In terms of upkeep, most pop-tops are virtually maintenance-free. The roof is one piece and thus leakproof as long as mounting holes for the tie-down tracks and the solar panel and wiring are properly sealed. One note: I’ve yet to find a brand of hydraulic strut that’s any better than any other (what I’d give to have Koni introduce a line), and the Mulgo top uses four, two each for the top and the bed. So we carry spares, plus a fail-safe backup: a three-foot-long stick, easily wedged to keep the top off our faces even if two struts blew out at once.

Our leap of faith into pop-top ownership was more fraught than most of you might experience: We had ours installed on a vehicle we bought sight unseen in Australia, and then had trucked to Sydney for surgery before we even arrived, to have a conversion installed we also had never seen. So you could say there was some trepidation.

One night laid that to rest. Three continents later, we’re still in love with the expedition-ready amalgamation of a 70-Series Troop Carrier and a mini-Winnebago. The biggest “problem” we face now is the extra time needed to chat with the people drawn to it as if by rare-earth magnetism everywhere we go.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.