Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

ARB Solis driving lamps

I’ve written before about my admiration for ARB’s Intensity driving lamps. We have a set on both our Troopy and the FJ40, which have saved us from, respectively, kangaroo and cow strikes on remote roads on two continents.

The lamps on the Troopy are first-generation Intensity lamps, and I would have considered it difficult to improve on them, but in 2019 ARB introduced a V2 version with 35 percent more power. I put those on the FJ40, and indeed they are noticeably (even) brighter.

But now, just a year later, ARB has introduced an entirely new lamp, the Solis.

At first glance the Solis looks like another update of the existing, larger Intensity V2 AR32 (the Solis at present only comes in the larger size; there’s as yet no equivalent to the smaller V2 AR21). But there are actually quite a few design modifications, one major difference—and one huge difference.

The 32 in the V2 Intensity name refers to the number of Osram LED emitters in the lamp. The Solis ups this to 36, and, moreover, splits their duties. There are 30 4-watt emitters in the perimeter of the lamp, and 6 10-watt emitters in the center, to give some extra reach in the center of the beam, even in the flood-patterned model. As a result, the performance of both the spot and flood model of the Solis exceeds the V2 AR32 Intensity by about 20 percent.

The major difference is that the Solis is dimmable over a five-stop range, via a remote-control wand. On the surface it might seem pointless to build a 165-watt Osram-powered driving lamp and then make it dimmable, but in fact there are many situations in which you want more light than your high beams can provide, but less than the Solis’s full 9,500 effective lumens. On winding roads lined by trees, for example, the glare from full-powered lamps can be a hindrance. The reflection from road signs can also be nearly blinding at times. If there’s a lot of dust or moisture in the air you might be better off with less reach.

Remote controls the five-step dimming function

And the huge difference? That’s the price. The V2 AR32 Intensity lamps retail for $783 each. The Solis lamp of the same size retails for $558. Per pair. With a wiring loom.

What explains this? You might have already guessed. The Intensity V2 lamps are manufactured in the United States by Rigid Industries. The Solis was engineered in Melbourne, Australia, and is manufactured in China.

I’m a bit conflicted about this, but not much. Sure, I’d prefer the U.S.-manufactured items and I’m glad those are the ones we have. But I’m fully aware that not everyone can spare that kind of change for driving lamps, and those people are prime targets for the many knock-off lamps that replicate the look of the Intensity lamps without their build quality. The combination of Chinese manufacturing . . . let’s call it “efficiency” . . . with, one fully expects, ARB quality control, should provide a reliable alternative for those who fainted when they read that first price above.

Are there any other cost-cutting approaches? Not that I can see from photos or specifications. The Solis has a cast-aluminum body, a one-piece reflector, a polycarbonate lens, and is submersible to three meters. It echoes a bit of the Intensity look with two red trim sections, but these can be swapped out for black if you prefer a more low-profile appearance.

My hope is that both these lines survive. I’m happy they’re both there, but I’ll be disappointed if sales of the U.S.-made product simply disappear in the face of the in-house Chinese competition.

I’m hoping to get a pair of Solis lamps to actually test soon. In the meantime, ARB is here.

Knipex: The right tool for the job

If you’ve ever needed to disassemble a Land Cruiser hub (or quite a few others), you’ve run into the retaining ring that secures the end of the stub axle. It’s not a circlip with holes that accept a standard snap-ring plier; the free ends come to bevelled points that are expletive-inducing to remove with any makeshift tool. Graham Jackson and I got them off our Troopy in the middle of the Australian bush by filing flat shoulders in the tips of a pair of his needle-nosed pliers. But it was still a dicey job to avoid having the things sproing off 20 feet into the dirt.

Rather unbelievably, I’d been through this same procedure at least a dozen times on our other Land Cruisers, from my 40 to our FJ55 to our FJ60. Every expletive-filled time I thought, I need a proper tool for this (expletive) job!

Finally I got one, and oh brother what a difference. It’s from the German tool maker Knipex, and it turns the task of removing and replacing this ring into an effortless and expletive-less five-second procedure.

If you drive a Land Cruiser and carry a tool kit for field repairs, get one, part # 4510170.

You’ll thank me some day.

Swarovski NL Pure binoculars . . . a new paradigm?

One of my favorite binocular interactions took place when Roseann and I were caretakers in Brown Canyon, in the Baboquivari Mountains about 50 miles southwest of Tucson.

Among our duties was leading hiking and birding tours along the canyon’s sycamore-lined creek.

After we’d taken one group up to a natural arch on a morning walk, we all gathered on the big shaded porch of the caretakers’ house to have lunch and look at birds on our feeders and in the trees. At the time I was using Leica BN 10 x 42s, one of the best two or three of its type in the world, and one of the guests was an amiable but crusty older fellow who had spent much of the hike teasing me about the fact that his binoculars cost less than a fifth of what mine had.

Now he came and stood by me while we both leaned on the porch rail and scanned the trees, and started right in again.

“I’m sure they’re great and all, but mine do just fine. I just don’t see how those can be worth the money.” I had mostly smiled and shrugged up to this point, biding my time.

Soon, though, he spotted something and said, “Kestrel in the big dead tree on the other side of the creek. Can’t tell if it’s male or female. (Male kestrels are most easily identified by their blue-gray shoulders.)

I looked through the Leicas and said, “Male.”

He eyed me dubiously. So I took off the Leicas and held them out.

He accepted them with an exaggerated show of care and looped the strap around his neck. He looked through them toward the tree, adjusted the bridge to fit his face, looked again. He pulled them down and looked at me, then looked through them again. He did a slow sweep of the canyon, looked up at the top of the ridge, looked down at the blue-throated hummingbird at one of the feeders. Finally he pulled them off and held them out to me, and with a deep, shuddering, what-have-you-done-to-me sigh, said, “Okay. I can see how they’re worth the money.”

Let’s be honest: Not everyone needs a binocular that costs as much as a decent used car. (Side note here: I bounce back and forth randomly between referring correctly to the instrument in question as “a binocular,” and referring to it in the vernacular as “a pair of binoculars,” which of course it really isn’t.)

As a natural-history writer, guide, birder, and hunter I’ve always felt justified in spending whatever it took to carry the best optics, just as an auto mechanic might justify Snap-on tools, or a graphics designer an 18-core iMac Pro. But let’s continue the honesty: Many people, including me, unapologetically derive great satisfaction and joy from using the best of whatever equipment they employ, whether or not it might be a deductible expense. I can justify high-end optics, but in the end I simply enjoy them, and never tire of the sharp intake of breath I experience every time I magically bring a bird or a whale or a distant landmark or a Ferrari on a race track ten times closer.

The stratospheric upper echelon of binocular performance is a battleground in which three manufacturers, and sometimes a fourth, fight for dominance with instruments that are in every sense pinnacle products. These manufacturers—Leica, Swarovski, Zeiss, and occasionally Nikon when the company is feeling feisty—spare no expense to make their flagship product as perfect as it can possibly be, and damn the cost. The best glass, coatings, and prism designs to produce the brightest, sharpest image; the strongest and lightest materials to gain supreme durability, weatherproofness, and comfortable long-session viewing; and the latest technology to stay abreast or incrementally ahead of the current competition’s best.

Thanks to that, “Hey, I’m a pro, I need the best” justification, plus the opportunity to review binoculars a couple dozen times over the years, plus just general binocular geekness (I own . . . several . . . including a Zeiss 10 x 40 BGAT from West Germany, arguably the very first ultra-premium binocular), I feel competent to judge differences in high-end binoculars sometimes measured in a percentage point of light-gathering ability, or a molecule-wide fringe of chromatic aberration, or a couple of feet of field of view, or an ergonomic detail unnoticeable unless you’d had the instrument to your eyes for a solid half hour. For at least the last decade it was only such minute variations that defined the differences among the big three and the notion of which one among a transcendent group was “best.”

Until last month, that is—when Swarovski introduced their entirely new NL Pure line of roof-prism binoculars, in 8 x 42, 10 x 42, and 12 x 42.

I have a connection to Swarovski that goes back to the 1980s, when I bought a pair of their Habicht 10 x 50 porro prism binoculars, magnificent and bulky beasts that I used while guiding sea kayak trips in Mexico, simply strapping them down on the deck of my boat where waves frequently washed over them. They performed flawlessly for a decade until I decided to move to a more compact roof-prism instrument, at which point I sold the Swarovskis for more than I had paid for them.

My current binocular is a Swarovski 10 x 42 EL, a brilliant instrument built in the double-bridge style the big three adopted for their top-end products a few years ago. To get a feel for how good these things are, go outside and look at a car or tree a hundred feet from you, then walk up until you are ten feet from it. That’s what the view is like through the ELs—the world is simply ten times closer. The only things less than perfect about the ELs (for me) is that the molded-in thumb grooves don’t quite match where I put my thumbs—obviously a personal-fit issue—and the fact that the big focus wheel sits slightly behind the neck strap lugs. I like to keep two fingers on the focus wheel because I’ve developed a technique of “walking” my index and middle finger rapidly across the wheel to go instantly from close to far focus, and on this binocular the strap lugs lightly dig into my hands when I do this.

When I pulled the new NL Pure 10 x 42s out of the box, it was apparent the ergonomics were going to be in a different league. The optical tubes of the single-bridge design (which I prefer, although strictly for aesthetics) were markedly constricted in the center, giving the binocular an elegant wasp-waisted look. More important, that constriction made the NLs the easiest full-size binoculars to hold I’ve ever used, even one-handed.

It’s easy to get a full wrap on the narrow barrel

I’m told the engineers accomplished this through the why-didn’t-someone-think-of-this-before strategy of rotating the binocular’s Schmidt-Pecan roof prisms, but I haven’t yet seen an internal view of the optics so I don’t know if any other tricks were employed. In any case, when I tried the NLs I was immediately convinced they were lighter than the ELs—not so, they’re actually a few grams heavier but don’t feel it.

One-handed use is easy with the NL Pure

The focus wheel was another pleasant surprise—it’s now in front of the strap lugs and falls perfectly to hand, or finger as it were. I can finger-walk the Pures from their excellent close focus of just 6.6 feet out to infinity in a couple of seconds.

Focus wheel is perfectly positioned

But ergonomics were almost secondary to the real news. The NL Pure introductory video promised a new high water mark in the field of view for full-size binoculars, and that was an understatement. In the past one brand or another would boast of a field of view three or four feet wider than its competitors at 1,000 yards. I’d have to look through one, rolling my eyes back and forth, then through the other, doing the same, before finally concluding, yep, a bit of difference.

Optics transmit 91 percent of available light. The black inserts can be swapped out for hinged objective-lens covers for those who prefer them.

Not the Pures. I looked through my Leica 10 x 42 Ultravids, then through the NL Pures, and wham. The difference was stunning: 336 feet to a horizon-spanning 399. I looked through my own Swarovski 10 x 42 ELs—until now the company’s top of the line product—and then the NL Pures, and wham. Same difference. The field of view of the 10 x 42 Pures is the wide as the company’s 8.5 x 42 ELs. The only binocular I’m aware of that comes close to the field-of-view performance of the NL Pure is the Zeiss Victory 10 x 42, at 394 feet.

The challenge with providing such a wide field of view is maintaining sharpness all the way out to the edges of the field. The wider the field, the harder that is to do, and the greater likelihood of distortion and chromatic aberration as well. As near as I could tell, the Pures maintain sharpness and color to the edge of their 399-foot vew as well as the ELs do to their 336-foot view—that is, superbly.

Diopter adjustment is on a toggle behind the focus knob

So far, so spectacular. But along with the NL Pures the company sent a new (extra-cost) option: the FRP, (for Forehead Rest Pure, I think). And I have to be honest, when I saw this device for the first time I laughed out loud. It reminded me instantly of the Optigrab, Steve Martin’s ill-fated eyeglass accessory from The Jerk.

Not a gimmick. Really.

The forehead rest is exactly what it says—a small, adjustable pad that plugs into the bridge of the binocular after removing two screws. A dial moves it in and out to achieve gentle but solid pressure on your forehead to help stabilize the view—a problem for some people using 10-power binoculars, and probably a problem for most people using the NL 12-power instrument.

So, in the interest of due diligence, I removed the two little screws, plugged in the Optigr . . . I mean forehead rest, and went outside to try it.

And. Well. Dammit . . . the thing actually works. I’m very steady with 10-power binoculars, but using them with and without the rest I could beyond any doubt feel the difference—and trust me, I didn’t want to feel a difference. I instantly knew of a situation where this device would be a huge advantage for me: When I hunt deer or elk I normally do what is called, illogically, still hunting, which involves moving slowly through habitat and stopping frequently to glass. I always do this one-handed, keeping my other hand on the rifle. And the Pure forehead rest dramatically increased stability when I held the binoculars one-handed. (I often do this when hiking and looking for birds, too, come to think of it. And Roseann does it all the time while sketching.) Suffice to say the FRP works as advertised.

Even the NL Pure soft case is innovative. It opens sideways like a clamshell and the binocular lays in on its side. It’s far easier to access and store them than in the traditional vertical case. Well done Swarovski for rethinking something so mundane.

Quibbles? Okay: The strap incorporates a clever way to adjust its length instantly, but it leaves tails of strap flopping around. Since these weren’t mine I did not try simply cutting them off shorter . . .

Ergonomics, clarity, field of view. For the first time in years, I found a new premium binocular model to be a big leap from its predecessor, and a leap ahead of its competition. If you can justify the expense, you’ll find The Swarovski NL Pure worth every penny. If you can’t justify it, maybe consider a career change?

Swarovski is here.

Classic Kit . . . not. The snake-bite kit.

Jonathan (left, with a crappy homemade snake stick), Bruce Douglas, and Jeff Swanson about to head into the snake-infested hills.

As kids growing up in the Sonoran Desert, my friends and I were always aware of the presence of rattlesnakes in the terrain we hiked and played in. Not that it upset us—far from it. We thought it was the coolest thing possible, along with coral snakes, scorpions, and other, larger coolest things possible, like cougars in the mountains we camped in. We would have been big fans of Doug Peacock’s later observation that, “It’s not wilderness unless there’s something out there that can kill you.” But we knew always to watch where we put our feet and hands, and always to look down before stepping out a door—an instinct so deeply ingrained that I do it when stepping out of a pub in London.

In those early days, if we saw a rattlesnake while on a backpacking trip we usually killed it—it was simply the accepted thing to do then. To be fair, we also usually skinned, roasted, and ate it, so it wasn’t simply murder. Later on we learned a more tolerant attitude—but we never stopped being aware of the possibility that one day you might let down your vigilance, or just have a second of bad luck.

That was okay—because we had snake-bite kits. Identical to the rather alarmingly suppository-esque looking thing shown here.

Cutter (later better known for insect repellent) first produced these in the 1950s as far as I can tell, but by the 1970s they were official Boy Scout items, issued to the military in Vietnam, and eventually copied by several companies such as Coghlans and All-Molded Plastics (the one shown here).

The kit comprised two rubber halves, designed to be suction cups, and a smaller one inside for use on fingers. Also included were scalpel blades, an iodine ampoule, and a cord to use as a tourniquet. According to the instructions, if bitten you were supposed to tie the tourniquet above the bite to restrict circulation, lance each fang mark in a cross pattern with the scalpel blade, then use whichever suction cup was appropriate to suck out the venom. And Bob’s your uncle, right?

Actually, no. It’s fortunate we never had to use one of these things as directed, because we almost certainly would have done more harm than good, especially with that tourniquet, assuming we didn’t lance a major artery, and hadn’t spent a half hour following directions instead of heading for home and a hospital.

Many studies (such as this one, of a much more sophisticated device, the Extractor) have shown that not only do suction devices not remove a remotely significant amount of venom, they can actually delay the healing process by weeks due to severe localized tissue necrosis at the site of application. The best snake-bite kit today is universally recognized as a set of car keys, to get the victim to a hospital for proper treatment with a polyvalent anti-venom. In the U.S., fatality among snake bite victims is well under one-half percent. In fact—I looked this up years ago for a book and verified it—more people in the U.S. die each year from accidentally pulling vending machines over on themselves than die from snake bite. Intriguingly, both types of victims tend to be young males . . .

The good news is, the futility and potential harm from using one of these devices is now common knowledge. No reputable company would think of marketing a product proven to be as ineffectual as blood-letting, lobotomies, and, well:

Or . . . maybe not.

In fact, Coghlans still sells their kit in hardware and outdoor stores across the country. Not only that, but in researching this piece I came across an article on a site called Pestwiki.com titled, “The Five Best Snake Bite Kits for Survival,” published in 2019. Number one? The Coghlan’s kit.

It’s followed by the Extractor (see study above) and several others. Then, after telling us which are the “five best snake bite kits,” they follow it with a sort-of kinda maybe caveat:

Note that bit, “ . . . they do remove some fluid but extract much venom.” Typo? If so it’s a doozy.

Postscript: By the time I was 14 or 15 I’d given up killing rattlesnakes, and instead was keeping them in cages in my bedroom, right under the nose of my stepfather, who would have put me out in the street if he’d found out.

Much more fun than eating them.

Pinnacle products: A white paper

“There are dinner jackets, and dinner jackets. This . . . is the latter.”

If you recognized the line—and, more important, if you smiled and nodded approval—then I don’t need to introduce you to the concept of a pinnacle product. But on the slim chance you aren’t a Bond movie fan, let’s talk.

It’s axiomatic that the overwhelming majority of consumer products have to be compromises.

This is because, above all, a product has to sell to be successful, to earn a profit for its maker. Thus function, performance, weight, ergonomics, style, durability, reliability, sustainability, fair labor practices—a hundred parameters—might each be considered and incorporated to lesser or greater degrees depending on how much it costs to include each one—or perhaps rather how much profit it takes away. And generally a product that includes all of them simply costs too much to produce and offer at a price most consumers will (or can) pay.

But for a scant few products, a scant few manufacturers through the years have chosen to throw this paradigm out the window. Those manufacturers ignored their accountants and made the product the best they could possibly make it—and figured out afterwards how much they needed to charge for it to make a profit.

Sometimes this bold approach works; other times it does not. Consider, for example, the 1992 McLaren F1—still considered by most automotive experts to be the finest supercar ever produced. The designer, Gordon Murray, overlooked not a single detail to make the F1 the best it could be. Components as seemingly unimportant as the throttle pedal had days and days of design input and were made from the finest and lightest materials available—then remade again and again until they were perfect. The exhaust heat shield was gold foil, because gold reflects heat better than any other metal. The proof of the F1’s brilliance came when a barely modified example won the 24 Hours of Le Mans outright. Twenty eight years later the F1’s 242 mile-per-hour top speed has not been topped by another naturally aspirated vehicle.

And yet. McLaren planned a production run of 300 F1s—but only 106 were ever made. It was ahead of its time, and it was exceptionally expensive: $800,000. By comparison a 1990 Porsche 959—a pinnacle machine of its own—ran about $300,000 (although it’s thought Porsche lost at least $200,000 on each one it sold).

So producing a pinnacle product is clearly a risk, even if it is considerably less expensive than that F1.

A pinnacle product does not have to be the best at everything; it simply needs to be the best at what the manufacturer wanted it to be. The early decades of Rolls-Royce motor cars exemplify this. The first Silver Ghosts weren’t intended to be high-performance or even particularly luxurious. They were built to be supremely reliable and durable, and they were, winning numerous reliability trials, and leading an outside source—The Autocar —to proclaim the Rolls-Royce “The world’s best motorcar,” a slogan the company quickly adopted. In fact the early Rolls-Royces were reliable and durable enough that they went to war, serving with T.E. Lawrence in the Middle East and modified with armor for other campaigns.

A pinnacle product can be a classic—that Silver Ghost, or the Wehrmacht jerry can, for example—but a classic product isn’t necessarily pinnacle. The original Land Rover essentially defines classic in the world of expedition vehicles, but it was built within numerous cost-cutting parameters, chiefly due to the rationing of steel and the extreme economic difficulties faced by the Rover company and England in the late 1940s. The box-section chassis, for example, was an elegant solution to the need to reduce the amount of steel in each vehicle while retaining adequate torsional rigidity, but the material was necessarily thin and thus very prone to rust issues, and for reasons of cost was never galvanized—a compromise that endured through the end of production in 2015.

A pinnacle product can be eclipsed in performance by a later product that doesn’t qualify as pinnacle, simply because technology advances to the level where even less-than-pinnacle technology is better than what came before. It’s undeniable that a modern DSLR camera produces higher-quality images than could be produced by a 35mm 1954 Leica M3. But the M3 (another example of a product both pinnacle and classic) was made with single-minded attention to craftsmanship and durable function. Today’s cameras, however well-built they may be, are constructed with the secure knowledge that they will be outdated within five years. No modern DSLR will be held in the same regard 60 years from now as the Leica is.

Pinnacle products do not necessarily have to be expensive items, although in virtually all cases they are among the most expensive products of their type. I’d consider Snow Peak’s double-wall titanium coffee mug an example of a “budget” pinnacle product, and at $50 it’s attainable—but a perfectly serviceable stainless substitute can be had for a fifth the price.

I’ve decided to start a new, occasional entry on Overland Tech and Travel, nominating and telling the story of a product I view as pinnacle. Most will have at least something to do with overland travel, but not necessarily—some might just be interesting.

These stories won’t be simply slavish homages to absurdly expensive consumer products. Many times the technology or materials that are introduced or proven in pinnacle products subsequently trickle down to more affordable products. Thus it’s worth investigating the former even if you think the idea of spending $50 on a coffee mug—or $800,000 on a car—is insane.

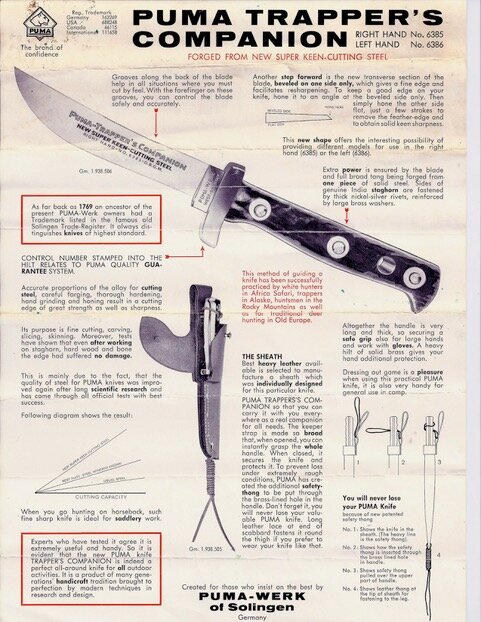

Also, I believe any pinnacle product should above all serve a purpose and be used for that purpose. Consider, for example, the knife pictured above. It was my introduction to the concept of (and, okay, obsession with) pinnacle products.

As a teenager itching to spend yard-work money on my first real knife, I pored over the usual Field and Stream ads for Buck, Schrade, and Western—but with my first look at an ad from Puma, I knew there was something different about them. Even in black-and-white the superior fit and finish was obvious. They were forged in West Germany, individually serial-numbered. The scales were Sambar stag, not plastic or jigged bone. Every Puma knife displayed a tiny indent on the blade where the steel’s correct hardness was confirmed with a diamond point. (You can see it here just off the corner of the “P” in Puma.)

Even among the various beautiful Puma models there was one that jumped out at me. It was called the Trapper’s Companion—the very name whispered of wilderness adventures. It had the most beautiful lines I had ever seen on a knife: The blade showed the even, perfect sweep of a saber, or the sheer of a sailboat. The blade was bevelled on one side only—something I’ve not seen since in a knife—and thus could be ordered in right or left-hand configuration. For a left-handed kid this made it all the more entrancing.

Even the sheath was special—a full-length, protective leather cover with an embossed puma head, and a leather thong that threaded through a hole in the knife’s handle to secure it against loss.

Puma produced a full-page information sheet for the Trapper’s Companion, including exhaustive descriptions of each feature—which I memorized down to the last detail.

Image courtesy pumaknifeman.com

There was just one problem. The Trapper’s Companion cost an astronomical $32—at the time when a Buck Personal was $14.

So, bowing to teenage economic reality (and impatience—my best friends already had good knives), I bought the Buck. And it was a fine knife. And meanwhile, my pinnacle knife, the Trapper’s Companion, did not sell well at its premium price, and was soon dropped from the importer’s catalog.

But I never forgot about it. I never threw away the ads I had cut out. And decades later, I found a Trapper’s Companion in fine condition on eBay, and paid somewhere around, er, ten times its original price for it. You could easily imagine I then put it on a shelf to admire, but I’ve field-dressed deer and elk with it. I wish I could travel back in time to visit that teenaged me and show him.

I’ve been accused more than once of being a snob, or elitist, or at the very least too attached to the idea of having stuff. I maintain my philosophy is almost exactly the opposite. That early penury drove home to me the real value of high-quality equipment that lasted longer and was thus actually cheaper in the long run than products that cost less to begin with. In 1983 I bought a Marmot Grouse sleeping bag that was insanely expensive at the time—a true pinnacle product sheathed in cutting-edge Gore-Tex and stuffed with the best goose down available. Thirty seven years later that bag is still in perfect condition and has lost at most a half inch of loft. Who knows how many fiberfill bags I would have used up and given away over the same period? My SVEA 123 backpacking stove is ten years older than that; I think it’s earned its steep $12 price several times over.

So there’s my introduction to and explanation of the new series, along with my first pinnacle product. Much to come. If you have any suggestions I’d be happy to consider them.

Even if it’s a dinner jacket.

(Postscript—tragically, the Puma company changed hands twice in the 1980s and 1990s, some production was moved out of Germany, and quality overall plunged. The pinnacle era of the Puma Knife Company was over. Older Pumas now command a substantial premium. See some really fine ones here.)

The ARB BASE roof rack

A couple of weeks ago I got a media release from ARB—an invitation to a video presentation introducing “one of the most significant products in ARB’s history.”

I was suitably intrigued. It’s no secret that I find ARB’s products to be consistently among the very best on the market, and several of them—the Twin air compressor, the ARB diff lock, the Intensity driving lamps, Old Man Emu suspension—have no peers. In fact, the only recent ARB product that underwhelmed me was their Pureview 800 flashlight, a serviceable but mediocre effort.

So what could “one of the most significant product’s in ARB’s history” be?

I considered. Hmm . . . what about a winch? That seemed to be a notable hole in the inventory. Given that the two best winches on the market right now—the Warn 8274 and the Superwinch Husky—are each decades old, an opportunity seemed to present itself.

Others: an overland-capable trailer? Several Facebook friends suggested products for the upcoming Ford Bronco. Hmm . . .

So I tuned in at the specified time, typed in my super-secret media password, and heard that what I would be learning about was ARB’s new . . . BASE roof rack (for Build, Attach, Set, Explore).

Wait. Seriously, I thought? A roof rack? That’s it? But I settled in to watch.

And, the more I watched, the straighter I sat in my chair and the closer attention I paid.

No, I wouldn’t call a new roof rack earthshaking, even from ARB. However, I do think the company has advanced roof-rack design by a significant leap over the competition. Here’s why.

The basis of the rack is a fully welded aluminum structure, available in six sizes, from 45 by 50 inches up to 50 by 84. Each member is of hollow, boxed construction, with an additional internal reinforcing strut running its entire length—lending great strength with minimal weight. The rack’s crossbeams are oriented transversely, which reduces each beam’s length compared to longitudinal beams, further increasing rigidity. (Transverse beams also offer better support for carrying long items.) The only potential downside is increased wind noise, and ARB claims their tests indicate that most noise is generated at the front beam, for which they have introduced a wind deflector. The only bolts in the rack are on the corner pieces, which can be removed to run wiring internally.

The really clever innovation is the dovetail extrusion running along the side of each beam, to which all the tie-down brackets and accessories mount. Since the dovetails sit below the level of the rack floor, they do not interfere with cargo. Unlike T-slots, they will not pack up with dirt and debris, yet placement and arrangement of tie-down points and accessories is virtually unlimited, and the full strength and stiffness of each beam runs through the dovetail. (If you already have a bunch of T-slot accesories, adapters are available.)

The dovetails make it easy to equip the rack with a perimeter rail in whatever configuration you like: full, quarter, three-quarter, and “trade,” the latter of which only runs along the sides to facilitate loading ladders, lumber, etc., and would be the way to go if you carry an Oz Tent.

The dedicated premium mount for a Hi-Lift jack is brilliant. The mounts rotate out to form a cradle for the jack, making it easy for one person to load or unload. Well done.

Eyebolt attachments for the dovetails facilitate the use of standard ratchet straps; ARB also offers custom ratchet straps with dovetail-compatible ends.

A recovery track base allows fitment of brand-specific attachments for MaxTrax and other recovery boards. And of course there are specific mounts for a range of other accessories—not all of which I recommend carrying on a roof rack at the same time.

I’m not a fan of roof-rack mounted driving lamps; nor am I a fan of light bars; however, ARB has designed a very stylish light bar that integrates beautifully with the front of the rack. You might not have even noticed it in the photo above.

Of course a full range of mounting brackets will be available in addition to a rain-gutter option.

I think roof racks should be used and loaded with discretion, for reasons of weight and CG in addition to windage issues. However, if you need one, first impressions are that the ARB BASE rack should be at the top of your list. I hope to lay my hands on one soon and give it a full workout.

Why I don't (hardly ever) buy from Harbor Freight

Everyone knows it’s unsafe and stupid to work under a vehicle that is not firmly supported by jack stands. Well, it turns out it can be unsafe and stupid to work under a vehicle that is supported by jack stands—if you bought them at Harbor Freight.

Recently the company announced a recall of some of its jack stands due to “. . . the possibility they could fail under load.” Customers who returned their stands were given a refund or credit. Apparently many of those customers, being, shall we say, somewhat slow learners, used the credit to buy the jack stands with which HF replaced the defective units.

Wrong move. Harbor Freight just announced a recall of those jack stands, too. Reportedly these stands fail due to the use of old and worn-out casting equipment that produced shafts with insufficient tooth engagement.

I understand the need to economize. But there are right ways to do so, and wrong ways. I actually own a Harbor Freight product: a two-ton hydraulic press. I bought it because I needed one for a particular job and wanted my own, but I knew I wouldn’t use it more than every few years. I also knew that if it broke, no dire consequences would ensue. The structure is a simple steel framework, the ram an ordinary hydraulic bottle jack, easily replaceable. It wasn’t a tool that could injure (or kill) me if it failed, nor could it strand me in the middle of nowhere.

The Harbor Freight story is an object lesson in the economics of cheap Chinese goods. Sure, labor costs are lower in China, but don’t imagine for a second that’s the only way companies that manufacture there cut costs. I took apart a Chinese winch a few years ago, a winch that appeared to be an exact copy of a Warn XD9000 from the outside despite costing a third as much. Once you got beyond the exterior, however, the differences were stark.

Obviously not all products made in China are junk—or cheap. I’m typing this on a pricey Macbook Pro that proclaims in zero point type on the back, “Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China.”

If you’re going to go for a cut-price Chinese product, however, just make sure it’s not one that could turn you into a garage pizza.

ARB product launch

This is intriguing. ARB is usually pretty low-key with new product launches, but they’re making a bit of a splash with this one. Details after the embargo on July 21.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.