Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

A cheap, bombproof lens-shipping case.

For the first 30 years of my career as a writer/photographer, all my camera gear went with me on airlines as carry-on luggage, packed securely in a Pelican case. For 30 years, there were no enforced weight limits for carry-on items, so no one ever noticed that the loaded case eventually weighed upwards of 33 pounds. That changed on one flight to Australia, when the check-in clerk asked to weigh it, and actually laughed out loud when she hefted it. Pointing to the sign I hadn’t noticed that said, MAXIMUM CARRY ON WEIGHT 7KG (15 pounds), she demanded I offload half its contents into our checked baggage. There followed five minutes of panic as we rolled a couple thousand dollars worth of DSLR equipment into our clothing, stuffed it into the middle of our checked duffels, and prayed for the best. (Walking past the business-class check-in we noticed that the limit there was 14kg or 30 pounds, sort of giving the lie to our clerk’s assurance that the limits were to “balance the load.)

We were lucky and everything made it to Sydney intact, but it was obvious a new approach was going to be necessary given increasingly widespread carry-on weight limits. Henceforth I carried a single camera body and a couple lenses on board, and packed the rest inside hard cases in our luggage, knowing it would inevitably be subjected to casual treatment by baggage handlers who, even if they were conscientious, were invariably pressed for time.

Early this year I picked up one of Sony’s brilliant 200-600mm zoom lenses for my Alpha 9 camera, and decided it needed extra protection—and thanks to my long-past life as a fixer-of-most-things, I knew how I wanted to go about it.

At Lowe’s Home Improvement I picked up an ABS stand pipe, six inches in diameter and 24 inches long, for the princely sum of $8.95 plus tax. Back home I picked out a scrap piece of 3/4-inch plywood (it happened to be Baltic birch but ordinary plywood would suffice). I traced the outer circumference of the pipe twice, then traced another circle inside each, a bit more than the thickness of the pipe wall. With a jigsaw I cut out each circle, then used a router to relieve the outer edge so each cap would fit securely into each end of the pipe.

Next I set up the Sony lens next to the pipe, gauging its length with space left over for padding on each end. I marked the spot with a circumference of painter’s tape and trimmed the pipe with the jigsaw.

Nearly finished. I made sure the length was good, then used Gorilla tape to secure the “bottom” cap to the pipe, first with a piece around the edge, cut and overlapped thus:

. . . then with strips all the way across.

All that remained was to load the lens—wrapped in a plastic bag to keep it dust-free—well-surrounded by packing peanuts. On top I inserted the remainder of the roll of tape to re-secure it on the way home—and also, I hoped, to allow anyone who might open it for inspection to re-secure it.

With the top taped shut, the case felt utterly bombproof. You’d have to run over the thing with a tractor to damage it (perhaps not beyond the realm of possibility at a couple airports I know, but . . .). I still marked the outside with warnings.

Of course the case survived multiple flights to, from, and within Alaska with zero issues, and for once we felt zero stress consigning such a piece of equipment to the vagaries of checked luggage.

Total out-of-pocket cost: $8.95. Plus tax.

VDEG sale . . .

A revised edition of the overland bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide, is in the pipeline. We don’t know when it will arrive; we do know it will be slightly larger in format, lightly updated, and for the first time in half a decade will have a higher cover price. In the meantime, we’ve reduced the price of our remaining copies of the current edition to just $60. Among the dozens of emails I’ve received from previous buyers of VDEG, not one has said, “Not worth the price.” The universal reaction is exactly the opposite—this 600-plus page book includes everything you need to know for a three-day weekend exploration of a nearby park, or a three-month scientific expedition in the Sahara. If you’ve been looking for a perfect holiday gift for an overlander you know, this is it.

A guide to recovery jacks, for the beginner . . . or procrastinator

A few years ago I was helping lead a group trip along the Continental Divide, when one of the participants badly sliced a tire on his Tacoma on a back road in Wyoming. Roseann and I were riding tail gunner, and as we pulled up the driver had already chocked the wheels, retrieved the factory scissors jack, and placed it under the rear axle. But he was failing completely in his efforts to raise the axle and tire, straining mightily but futilely on the crank handle. Why? Because mounted on the back of the Tacoma was a Four Wheel Camper, which was in turn loaded with water, food, and supplies for a two week trip. We stopped, I got out my four-ton hydraulic bottle jack, and we effortlessly lifted the truck and swapped the tire.

With very few exceptions—such as the superb Italian-made hydraulic bottle jack supplied with solid-axle Land Rovers for some time—factory-supplied jacks are designed to minimal specs to lift the vehicle, on pavement, just high enough to change a tire. Load that vehicle up with bumpers, winches, roof racks, camping gear—or a camper—and you might find that jack whimpering under the load. Actually it would be you who were whimpering.

If you want something that can handle a tire change on a loaded vehicle, as well as recovery duties—for example to lift the vehicle off a high-centered situation, or to shovel substrate under a bogged tire, or insert MaxTrax—you need to step up the game with something rated to at least half to two-thirds the GVWR of your rig.

And then you have a major decision to make: Do you want to lift from up top, via a bumper or slider, or from below, via an axle or the chassis?

The advantage to a bumper jack is, first, you don’t have to crawl under the vehicle to lift it—nice for staying clean but also possibly critical if your 4x4 is buried right to the axles in sand or mud. Or water. Disadvantages? First, your vehicle must be equipped with sturdy, recovery-capable bumpers front and rear—and preferably with rock sliders as well—that will accept the jack’s tongue. Second, to lift a tire off the ground with a bumper jack to change it you have to cycle through the vehicle’s full suspension travel first, which can mean a foot or more of wasted elevation and leave the vehicle precariously tippy. Finally, bumper jacks tend to be heavy and bulky.

The axle/chassis jack is compact (with the understandable exception of the Pro Eagle here), doesn’t waste lifting height to raise a punctured tire, and with a few accessories can perform a variety of recovery tasks. But access to the underside of the vehicle is mandatory, and bottle jacks in particular tend to have limited lifting range—often only six or seven inches unless you buy a double-extension model, which will increase that by another four or five inches. Still paltry compared to the 30 inches or more of a bumper jack.

My suggestion: If you mostly need a sturdy jack for tire changing and occasional recovery work, look at the chassis jacks here. If you like to challenge yourself and your vehicle and frequently find yourself a bit buried, consider making room for the Hi-Lift or one of the ARB jacks.

Hi-Lift jack ($100 48” all-cast)

How many products survive a century virtually unchanged? Yet the antediluvian Hi-Lift still scores points in this group with its low price, rugged simplicity, ease of refurbishment, and versatility—it’s the only product here that will also function as a clamp or a (very slow) winch.

The Hi-Lift’s 4,660-pound rating has become the de facto standard for competitors, and in this group its range of lift is second only to the ARB Jack. Downsides include the Hi-Lift’s 29-pound mass and jam-prone lifting mechanism (the latter usually rectified with a dousing of almost any lubricant, including, according to my nephew, Keystone Light). Also, while proponents always bring up those “clamping and winching” functions, the number of times I’ve done either except to demonstrate it is exactly zero. (On the other hand, I once successfully sleeved a broken tie rod with a Hi-Lift handle and a bunch of baling wire.)

To lift a vehicle by a bumper with the Hi-Lift, you must raise the lifting tongue—along with the entire lifting mechanism—up the main beam to the height needed. Thus if you’re using the common 48-inch model and your bumper is 36 inches off the ground, you’re left with just a few inches of travel (since the mechanism can’t go all the way to the top).

The big red flag in the Hi-Lift’s manual of arms, as anyone who’s used one knows, is what I call the ZoD: the “Zone of Disfigurement” circumscribed by the arc the handle makes. Let your head stray inside this arc—whether you’re raising or lowering—and you’re asking for a broken nose or jaw if you lose your grip. When lifting a heavy vehicle—especially if the operator isn’t heavy—it can be difficult indeed to apply enough force to accomplish the task while simultaneously staying out of the ZoD. And lowering a load takes exactly as much force as raising it, so don’t let down your guard just because you’re letting down the vehicle. Losing control of the handle while lowering can trigger a feedback loop that results in the handle slamming against the beam and rebounding wildly, ratcheting the vehicle down all on its own.

I know experiencedbackcountry drivers who wouldn’t leave home without a Hi-Lift, and equally experienced backcountry drivers you couldn’t pay to carry one. Over the years I’ve migrated between both camps, so I’ll be no help—except to slyly point you to the product below.

Bloomfield Manufacturing is here.

ARB JACK ($833)

Think of the ARB Jack as a Hi-Lift that went to a very expensive finishing school. The coarse mechanical mechanism is gone, replaced with smooth and powerful hydraulics—my 115-pound wife can lift the entire loaded rear end of our 70-Series Troop Carrier. At one demo I gave at the Overland Expo using the front of an FJ40, a lifelong Hi-Lift user walked up and gave the handle exactly one pump, said, “That’s all I need to see,” and headed for the ARB booth. There’s zero possibility of face-altering kickback—let go the handle and it simply sits there waiting for you to get back to work—and lowering is quite literally a one-finger operation via a little red lever. While a Hi-Lift can only lower the vehicle in increments of an inch, the ARB can gently ease it down millimeters at a time.

In another sharp contrast to the Hi-Lift, to adjust the lifting tongue of the ARB Jack to bumper height, you only have to lift the tongue itself to the appropriate slot on the aluminum body, leaving the full lifting range of the jack intact—up to 48 inches. One quirk: Once the weight is off the ARB Jack when lowering, it does not drop free like the Hi-Lift; there is still a considerable amount of hydraulic resistance. You need to keep the red lever pressed and really lean on the jack to compress it. A separate compression-release button (suitably guarded to avoid inadvertent activation) would be a handy future modification.

The ARB Jack is 15 percent lighter than a Hi-Lift, and only 36 inches long in its carrying case. The sealed mechanism won’t jam in dusty conditions, and the base even has a clever cutout to facilitate breaking the bead on a tire. What’s not to like? I just hope you were sitting down when you saw the price. If you can rationalize—and afford—the difference, I will say that the ARB Jack is hands down superior to the Hi-Lift, and, while accepting that this aspect is in large part a function of the user, a far safer one as well. Also check out the ARB jack base, which smartly accommodates either the ARB or Hi-Lift jack foot.

One caveat: ARB recommends the Jack be stored upright to protect the seals. I store mine upright at home, but carry it horizontal in the vehicle. So far I’ve had no issues.

ARB is here.

Safe Jack Bottle Jack kit ($269)

There may be more versatile jack systems around, but none that also fits in a .50-caliber ammo can. The 27-pound Safe Jack “Sergeant” kit comprises a six-ton hydraulic bottle jack, a flat (chassis) and a curved (solid axle) lifting attachment, and three extension posts, one of them adjustable. Other Safe Jack kits, from “Private” to, yes, “General,” include fewer or more extras (all of which are available separately).

The range of extensions allows you to lift from an axle, the chassis, or a bumper, as needed. Its compact size limits the included jack to six inches of lift; however, as long as the post is compatible, you could pair the Safe Jack attachments to any bottle jack you like, such as the double-extension model I already owned. My Safe Jack kit hasn’t yet met a vehicle it couldn’t lift. A suggestion: Have a blackmsith make you a “wheel claw” similar to the one Tom Sheppard had made and carried in the Sahara for decades (configured for a specific wheel type), and your bottle jack will easily lift one wheel to allow the insertion of a MaxTrax or other recovery mat.

Safe Jack is here.

Tom Sheppard’s bespoke folding wheel claw lifts one wheel for insertion of traction mats.

Surplus M998 scissors jack ($75) and Agile Off Road chassis adapter ($90)

Gotta love military surplus. The heavy-duty (3.5-ton) scissors jack configured to lift the front or rear A-arms of the High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle—Humvee to most of us—is available by the score on eBay with case, ratchet handle, and extension rods, for around 75 bucks. Add Agile Off Road’s reversible billet-aluminum adapter and it will securely support your non-combat vehicle at either the axle or chassis. A reversible ratcheting handle means you don’t have to crank in a complete circle in a confined space—a brilliant idea—and as long as your truck weighs less than an up-armored HMMWV this jack will lift it easily to a height of 20.5 inches with the adapter in place. A generous 7 by 12-inch base plate ensures support in Middle-Eastern-theater sand, or any other kind. The lifting post on the jack has a bit of wobble built in; Agile Off Road recommends tack-welding this to increase stability. However, I used it as is and had zero problems. I now carry this setup permanently in my FJ40.

Agile Off Road is here.

Pro Eagle Off Road jack ($440)

A floor jack with off-road tires—why didn’t someone think of this before? Take a two-ton hydraulic floor jack—the easiest way ever to lift a vehicle on a concrete driveway—add solid axles and burly composite wheels, and you’ve got an all-terrain floor jack. The Pro Eagle rolled over my gravel driveway effortlessly, and lifted the entire front end of my FJ40 in a sandy wash without digging in more than a couple inches. Given the fat tires plus a full-length underbody “skid plate,” it shouldn’t sink in any substrate that doesn’t have a current. Pop on the adjustable extension post for a full 26 inches of lift height. I certainly wouldn’t carry this bulky, 52-pound jack for field duty in the FJ40, but if you’ve got a full-size truck or Sprinter (there’s also a 3-ton version) or are traveling with a group, it will make any recovery a breeze. And, of course, at home it’s an excellent shop jack (I sold my old standard floor jack). One operational note—like all such jacks, the lifting pad moves through an arc as it rises. If you employ the extension, and both the jack and vehicle are held stationary by the substrate, the extension can wind up tilted significantly at full height. Plan ahead.

A full-length bottom plate prevents sinking even in sand.

Pro Eagle is here.

ARB X Jack ($270)

Some of the jacks here are easy to operate; some are difficult to operate—but only one is effortless to operate. Situate the deflated X jack under the chassis of your 4x4, hold the inflation cone over the exhaust pipe or connect an air compressor to the Schrader valve, and the expanding bag will lift up to 4,400 pounds up to 30 inches in the air.

Truck buried to the bumpers with no way to get a bottle jack or Hi-Lift underneath? All you need is four inches of scooped clearance for the X jack to slide underneath. Stuck in rocks with no secure base for a bumper jack? The X Jack molds itself around virtually any substrate, and the hard rubber “teeth” on the bottom help prevent slippage. Included is a thick square of guard material to protect the already-stout envelope, but it’s best to remember this thing is still a heavy-duty balloon, and keep it away from bolt ends and hot exhaust pipes. I’ve seen two punctures resulting from (extremely) careless placement, although the envelope can be patched effectively with the included kit.

Another possible issue with the X Jack is compatibility with your exhaust opening. The jack’s connector is a simple rubber cone, and if your exhaust tip is rectangular you might not be able to achieve a tight seal, critical for inflation. In that case an air compressor will work, but it’s much slower—the X Jack likes a lot of volume and low pressure, the opposite of what most compressors produce.

Finally, remember that at full height your vehicle is supported on air inside a flexible casing; expect a bit of squidginess.

But then, you wouldn’t get under a vehicle supported only by any if these jacks, right?

ARB is here.

A final note: None of these jacks should be employed unless the vehicle is securely chocked. Among the best of that breed I’ve seen are the Safe Jack nesting chocks. One is slightly smaller than the other and so fits inside when folded, yet the pair is substantial enough to serve as chocks for winching duty.

A version of this article originally appeared in Tread magazine.

Defender 110 and Land Cruiser Troop Carrier: Unobtanium no more

Once unobtanium on U.S. Shores, these two expedition legends can now be had—for a price. Are they worth it?

By Graham Jackson

Images by Graham Jackson, Brian Slobe, and Jonathan Hanson

The images are ubiquitous, in National Geographic, in Geographical, on CNN and BBC, even on the web on Overland Expo and Exploring Overland: two of the most iconic and aspirational expedition vehicles in the world; the Land Rover Defender 110 Station Wagon and the Toyota Land Cruiser 75 Series Troop Carrier (Troopy).

Both come from the same generation, the Defender started production in 1983 (yes, I know, it wasn’t named “Defender” until 1990, but it’s the same vehicle) and the 70 Series (J7) started production in 1984. From that time they became common sights in videos and news reports from the furthest, most adventurous parts of the world. Every wildlife documentary seemed to have a 110 lurking in the background and every natural disaster video report seemed to have a 70 Series on hand. These two vehicles became legends in short order.

But for the longest time neither vehicle was available in the USA. Sure, in 1993 Land Rover imported 500 federalized Defender 110s, which now fetch staggering prices on the used market—a testament to the pent-up demand for this vehicle. Mining companies have imported 75-series Land Cruisers, but they are not road legal and spend most of their lives as workhorses underground, where the incredibly tough conditions means no other vehicle is adequate. Why neither Toyota nor Land Rover took the effort to bring the vehicles into the USA as a major model for sale to the public can only be answered by the penny-pushers and spreadsheet drones at either company.

However, examples from the golden era of these vehicles (mid-1990s) have now reached the 25-year-old mark, making them eligible for private import into the USA. The question is, are they worth it? Should you find a Defender 110SW or 75 Series Troopy and import it into the U.S.? Would either serve well as an overland or expedition vehicle here? Since I own both, I think I can offer some insight.

To be clear, I am referencing only the specific models mentioned. Obviously there are other Land Cruisers and other Defenders, and both marques have massive followings of experts who will call me out on any transgression, so let’s define what we are talking about:

In my opinion, the golden age for these vehicles was the 1990s, and the best of the best were the export models, which is what the UN and aid organizations typically got. For Defenders that means, at its base, the Rest of World (ROW) spec 110 Station Wagon with the 300tdi diesel engine and 5-speed transmission, in white. There are ROW spec pickups, 90s, 130s and 3-door 110s as well, but here we are looking at the Station Wagon, the 110SW. For the Land Cruiser, choosing a spec is even more murky; the J7 line has two model groups, five wheelbases, many body variations, and twenty-two different engines! Here we are looking at the HZJ75, the ‘heavy duty long wheelbase’ with the 1HZ inline 6 cylinder engine and manual 5-speed transmission with the enclosed or ‘troop carrier’ body—also in white. See the chart for specifics.

Analysis

Let’s get this one out of the way: They are both gorgeous. Something about the boxy appearance and the utilitarian stance; they exude confidence and capability even when parked. They are vehicles you cannot step out of and not look back at; like your ultimate crush, they command the eye. I put that solidly in the good list, because their legend is in no small part due to this. If you don’t find your eyes drawn back to the opening picture of this article, then . . . well, I’m surprised you read this far.

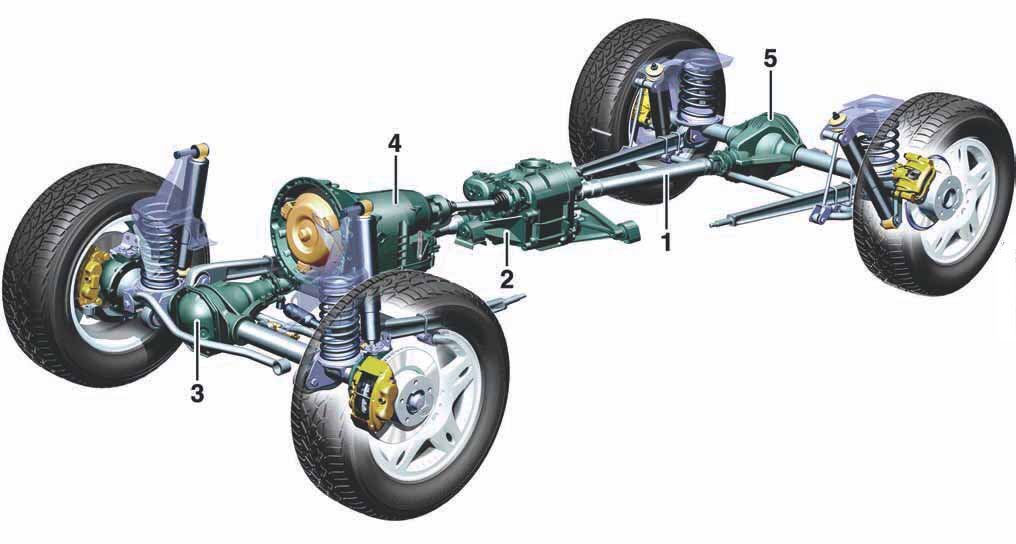

The rest of the “good” category pertains to the very utilitarian aspect that makes these vehicles excellent for expeditions and overlanding. Tom Sheppard and Jonathan Hanson have a fantastic comparison of the features in the Vehicle Dependent Expedition Guide, and I’ve included some in the chart here. Both are at the top of the range of available vehicles in terms of payload, in volume and weight, for their size. The Defender can carry a staggering 41 percent of its GVW as payload (with the heavy duty suspension installed), and the Troopy isn’t far behind at 30 percent, while the Troopy has a cavernous load bay at 87 cubic feet compared to the Defender’s at 77 (both with rear seats removed). As great load carriers, they lend themselves exceptionally well to expedition work, capable — with tried-and-true four-wheel-drive systems and suspension — of carrying the load over unforgiving terrain. The 110 has the more comfortable and compliant coil springs coupled with full-time four-wheel-drive, while the 75 has leaf springs and part-time four-wheel-drive with locking hubs—and, in many available examples, factory-optional cross-axle diff locks front and rear. The Land Rover’s fuel capacity is 21 gallons; the Troopy boasts dual tanks carrying a total of 47 gallons. Both come with five-speed transmissions.

Far from sport-utility-vehicles, these are just utility vehicles. No automatic transmissions, no driver aids like stability control or ABS—these are vehicles that have to be driven. They do not handle particularly well on the road, they lean excessively in corners when driven fast, and demand attention. But this is also an advantage. The lack of complex systems and sensors means that field repair is easier, and reliability is better. And no, I’m not going down the Land Rover reliability rabbit hole; Defenders are extremely reliable when cared for well.

Both the 300tdi and the 1HZ are stalwart expedition diesel engines that run on mediocre quality fuel, though the 1HZ is more tolerant. Both have simple mechanical fuel injection and can run on only one wire to the fuel solenoid if required — no computers to get in the way. But that also means they are not clean engines. They will pass 1990s emission standards, but nothing better. The 300tdi is a bit cleaner since it has a turbo, while the 1HZ will serve as an extremely good black fog machine at elevation. Neither are powerful. At 111 HP for the Land Rover and 129 HP for the Toyota, they accelerate slowly and cruise the same way. We will come back to this point later.

Toyota’s ultra-durable 1HZ six-cylinder diesel has been in production for 30 years.

Land Rover’s 300tdi is exceptionally fuel-efficient.

Luxury appointments are sparse, as are electronics. No electric motors in seats, no electric windows; sound systems that are barely able to drown out the noise of the engines and the road. They are not vehicles to drive with one finger at 85 mph while sipping a latte, texting friends, and jamming to tunes. The 75 does have tilt steering and optional electronic door locks, but no remote key fob. The 110 doesn’t even have those bare luxuries. Air conditioning is the one “luxury” shared by both, though some would argue it is a necessity (and it’s only optional for the 110SW). There are no speed sensors and interlocks to stop you shifting the transfer case while on the move and no backup sensors or cameras to help those who neglected to learn how to park or use mirrors. No clutch interlock to stop you starting the engine with the clutch engaged. Again, this speaks to their utilitarian drivability which is also one of their strongest assets. These are not nanny vehicles that assert “safety;” they are vehicles that demand attention, demand driving, and reward you in that you can start in gear when bogged in soft sand, or switch to high range while on the move so long as you double de-clutch.

Stock tire sizes are the same, at 235/85R16 (760R16), one of the most common light truck sizes in the world. Pretty easy to find almost anywhere. Given the simple non-electronic mechanics on both vehicles it is very easy to get them repaired.

The load bays on both models are spacious, sparse and square. Nothing better for building out a living space or a load system for any expedition. Unhampered by plastic trim, carpeting and cup holders, they are blank slates to build up and make your own.

Both vehicles lend themselves to camper conversions.

Which leads us to the two features that makes both of these vehicles so exceptional yet have nothing to do with Toyota or Land Rover. It is the massive aftermarket support in accessories and the equally massive community of owners who are willing to help wherever you go. Because of their highly customizable and modular nature (by design), it is very simple to make a 110 or a 75 your own unique expedition rig. From pop-tops to long-range fuel tanks to water tanks and interiors, to suspensions and underbody protection, both models have excellent support in this regard. The internet is filled with fantastic examples of beautifully outfitted vehicles. This also means that it can be very challenging to find one that is unmolested or even close to stock.

But don’t mistake all my praise to imply that either vehicle is perfect out of the box. One of the reasons that they have such massive aftermarket support is that they are, by all counts, mediocre when stock. Expedition vehicles are a collection of compromises and the 110 and the 75, in stock form, are exceptional in that they are completely un-exceptional. It’s like getting the highest quality blank notebook, with the finest acid-free paper and the most beautiful leather cover, case bound, that will last forever. But it is still a blank notebook until you put a few stickers on the outside and then fill it with stories and paintings of your travels to the most remote and beautiful parts of the world.

So . . . are they good for the USA?

In a word, no, I don’t think they are.

But that speaks more to the culture and circumstances of the U.S. than it does to the vehicles. In this country most people get very little time off, and distances are so great that a good portion of any overland adventure is going to be highway time. Neither of these vehicles is good at that. With a comfortable cruising speed of not much above 65 mph, both demand patience; with solid axles and archaic steering geometry, both demand constant attention. Many, many people have purchased a Land Rover Defender after falling in love with the safari image, only to sell it when they discover it is not a modern car, lacks anything close to a creature comfort, and requires diligent maintenance. If it is expected to be a mode of travel for family vacations, strife and frustration are often the result.

With that said, if you are a person with plenty of time who is happy to cruise at 65 mph and enjoy the scenery—and to be fair, there are quite a few who can and do (looking at you Maggie McDermut)—you might live happily with either of these vehicles, and will enjoy looking back at it every time you park and get out. When modified in any of the hundreds of variations possible, up to and including pop-tops, cabinets with sink and stove, hot shower systems, awnings, and more, once in camp they are the equal of any more “modern” vehicle.

Cabinetry turned this Troopy into a mini motor home.

Finally, of course, if you ever do have the opportunity to ship your Defender or Troopy overseas to Africa, Australia, or South America, you will be driving one of the premier choices for extended exploration in the remotest regions of the planet. It will be a notebook in which you can write your own adventures. If such a vision inspires you, I cannot recommend either of these vehicles highly enough.

Graham Jackson is the long-time Director of Training for the Overland Expo, and a founder of 7P Overland, a professional four-wheel-drive training and equipment-supply organization. Their website is here.

Think your 25-year-old import is safe? Think again . . .

There is a well-written, if disturbing, article by Andy Lilienthal over on Gear Junkie, here, about two states that are pulling registration from legally imported Mitsubishi Delica vans, for no logical stated reason. Their owners are being told to take the vehicles off the road—no loopholes, no grandfathering, just bang: The vehicle on which you spent thousands of dollars to purchase and import under valid U.S. law is now illegal to drive on the road in Maine and Rhode Island. Please mail in your license plates.

As the owner of a legally imported Land Cruiser Troopy worth several tens of thousands of dollars, this is a horrifying possibility to contemplate. Since states can set their own rules as to what is legal to drive, or not, on the state’s roads, an inimical legislature could render such vehicles illegal on any one of dozens of flimsy excuses. Steering wheel on the wrong side? Boom. Non-USA-spec engine? Boom.

The percentage of owner-imported vehicles within the entire U.S. market has to be risibly low for any legislature to waste time with such a thing. As Andy points out, a Model T is perfectly legal to drive anywhere in the country, despite being less safe, slower, and more polluting than any Land Rover or Land Cruiser—or Mitsubishi.

Here’s hoping some attorney will do a pro bono and fight this capricious movement.

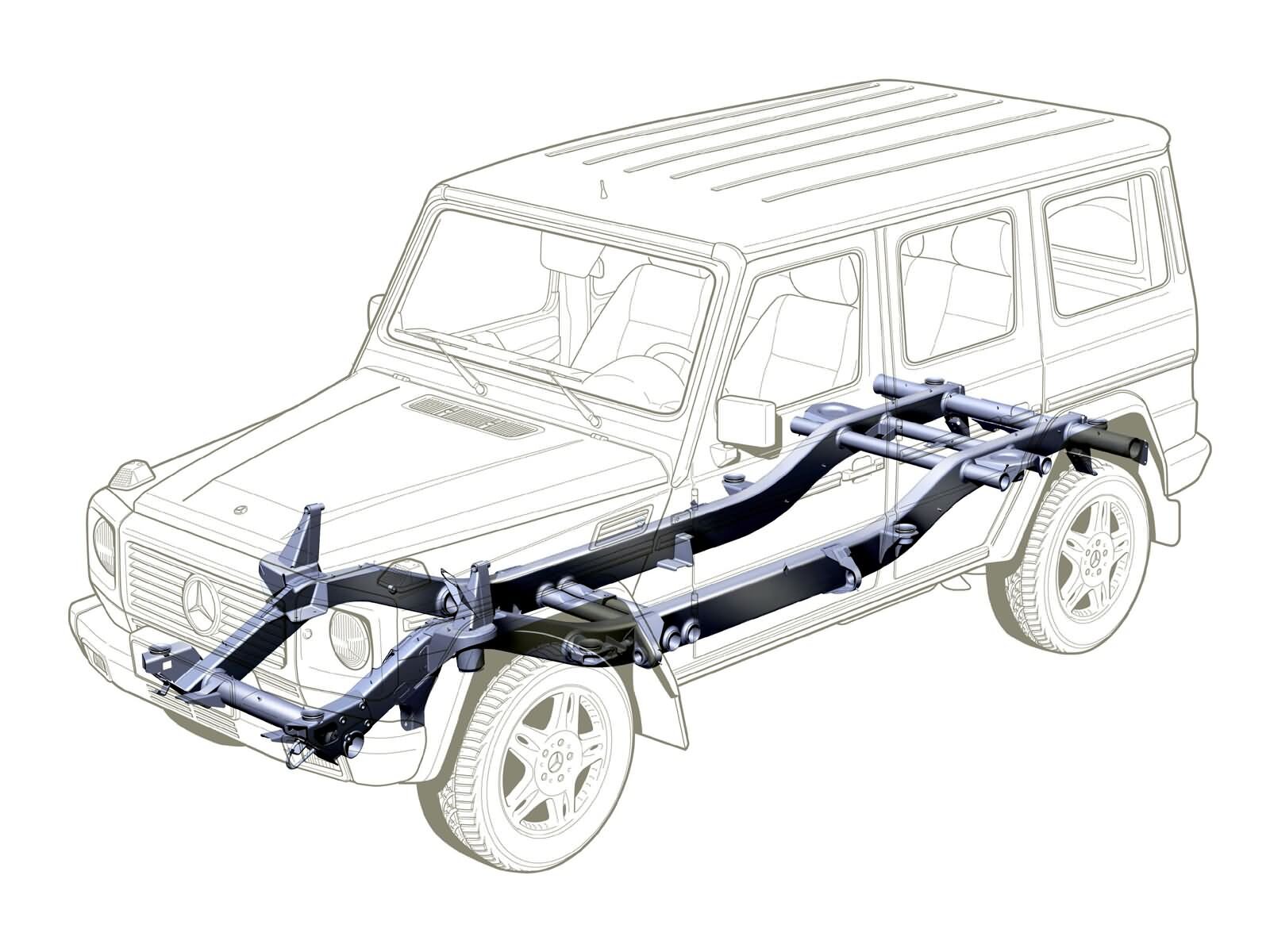

The new military-spec G-Wagen

The Mecedes G-Class—or Gelandewagen or G-Wagen, if you prefer—arrived late to the expedition scene: It was only introduced in 1979 as a military vehicle, designed at the urging of the Shah of Iran, at the time an important stockholder in Mercedes-Benz. (The Shah put in a pre-order for 20,000 of them, subsequently canceled when he rather abruptly became the ex-Shah.) Once civilian versions became available, a small contingent of explorers appreciated the Holy Grail configuration of the G-Wagen (and could afford its premium price)—a massive, fully boxed chassis with up to six tubular crossmembers, equally overspecced solid axles riding on an all-coil suspension, and cross-axle differential locks front and rear. No other mid-sized expedition machine combined all those features.

Fast-forward to today. The vast majority of G-Wagens are now sold bloated with luxury options (64-color ambient lighting, anyone?), and the most challenging expedition they’ll face is a gallery-hopping run up Canyon Road in Santa Fe.

And yet, the basic bones remain—despite a move to (gasp) independent front suspension in 2018. Over the years the company has offered various “Professional” models with overland-friendly bling-delete spec-lists. Now it has announced a new, military-only (for now) model referred to as the W464 (succeeding the W461).

The company hasn’t released detailed specifications; however, it is known the new version will benefit from significantly more power, thanks to a 3.0-liter inline six-cylinder turbodiesel, producing 245 horsepower and 445 pound-feet of torque, run through an 8-speed auto transmission. The W464 also has a heavy-duty 24-volt electrical system. Finally, photos indicate it retains a solid front axle.

In contrast to these business-like features is the civilian-spec (with IFS) W463’s new “Professional Line Exterior Trim” package, which includes mesh stone guards for the headlamps, 18-inch wheels with mild-looking tires, and . . . mudflaps. A nice-looking roof rack is an option, as is a swing-away spare tire holder, and some truly alarming body colors.

Not sufficient for your professional overlanding needs? You can also order the “Night Package,” which includes black mirrors and—ready?—a black three-pointed star in the grille. See above.

Dear Mercedes: Can we please have the W464 instead?

The Pro Eagle Off Road jack

A floor jack with off-road tires—why didn’t someone think of this before?

A floor jack is the easiest way ever to lift a vehicle on a concrete driveway. But most will be stopped in their tracks by a quarter-inch-diameter pebble. Pro Eagle took a two-ton floor jack, beefed up the chassis and added fat tires, and invented the all-terrain floor jack. The Pro Eagle rolled over my gravel driveway effortlessly, and lifted the entire front end of my FJ40 in a sandy wash without digging in more than a couple inches. Given the fat tires plus a full-length underbody “skid plate,” it shouldn’t sink in any substrate that doesn’t have a current.

The Pro Eagle barely sank lifting the front of the FJ40 in sand.

An adjustable extension post (stored near the base of the handle) pops on for a full 26 inches of lift height. I certainly wouldn’t carry this bulky, 52-pound jack for field duty in the FJ40 (although a convenient carrying handle helps moving it around), but if you’ve got a full-size truck or Sprinter (there’s also a 3-ton version) or are traveling with a group, it will make any recovery a breeze.

And, of course, at home it’s an excellent shop jack. I’ve abandoned my standard floor jack because the Pro Eagle is so much easier to move around—even in urban settings—and because of its greater lifting capability.

One operational note—like all such jacks, the lifting pad moves through an arc as it rises. A floor jack on concrete will roll slightly to compensate for this. If you employ the extension on the Pro Eagle, and the jack is immobilized in sand or rock, the extension can wind up tilted significantly at full extension. Plan ahead.

Pro Eagle is here. The two-ton model retails for $430.

2022 Toyota Tundra: Continuing the "My Grille is Bigger than Your Grille" Wars (EDITED)

Toyota has revealed some details of the 2022 Tundra. The most-featured news is the deletion of the long-serving V8 engine for a twin-turbocharged V6, following current popular trends in configuration and number of pistons. The top-of-the-line model produces 437 horsepower.

Other changes include rear coil suspension—a welcome upgrade and one the Tundra should have had from the beginning.

What I haven’t found out is if the Tundra’s sub-par “Triple-Tech” chassis, with open-channel frame members under the bed, has been ditched for a proper boxed chassis, as every competitor has. I still don’t know why the company abandoned boxed chassis in its trucks for a design similar to that found on Fords and Chevys in the 1970s.

More news as I uncover it.

EDIT: Ha! The 2022 Tundra has returned to a fully boxed chassis. Thank you Toyota. Along with the coil-sprung, multi-link rear axle, this represents a genuine leap in the design of this truck.

Three cheers!

Now, can we talk about that grille?

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.